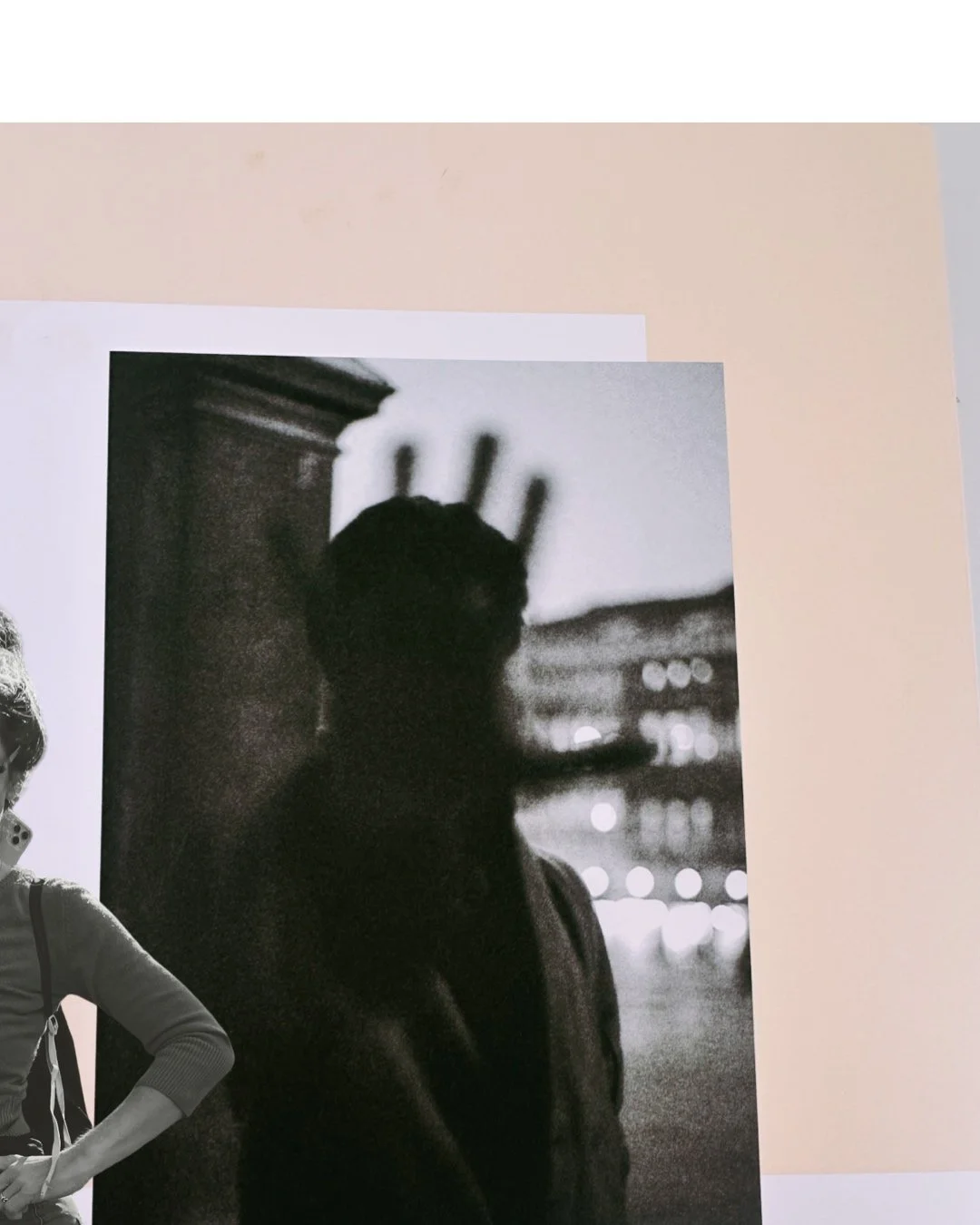

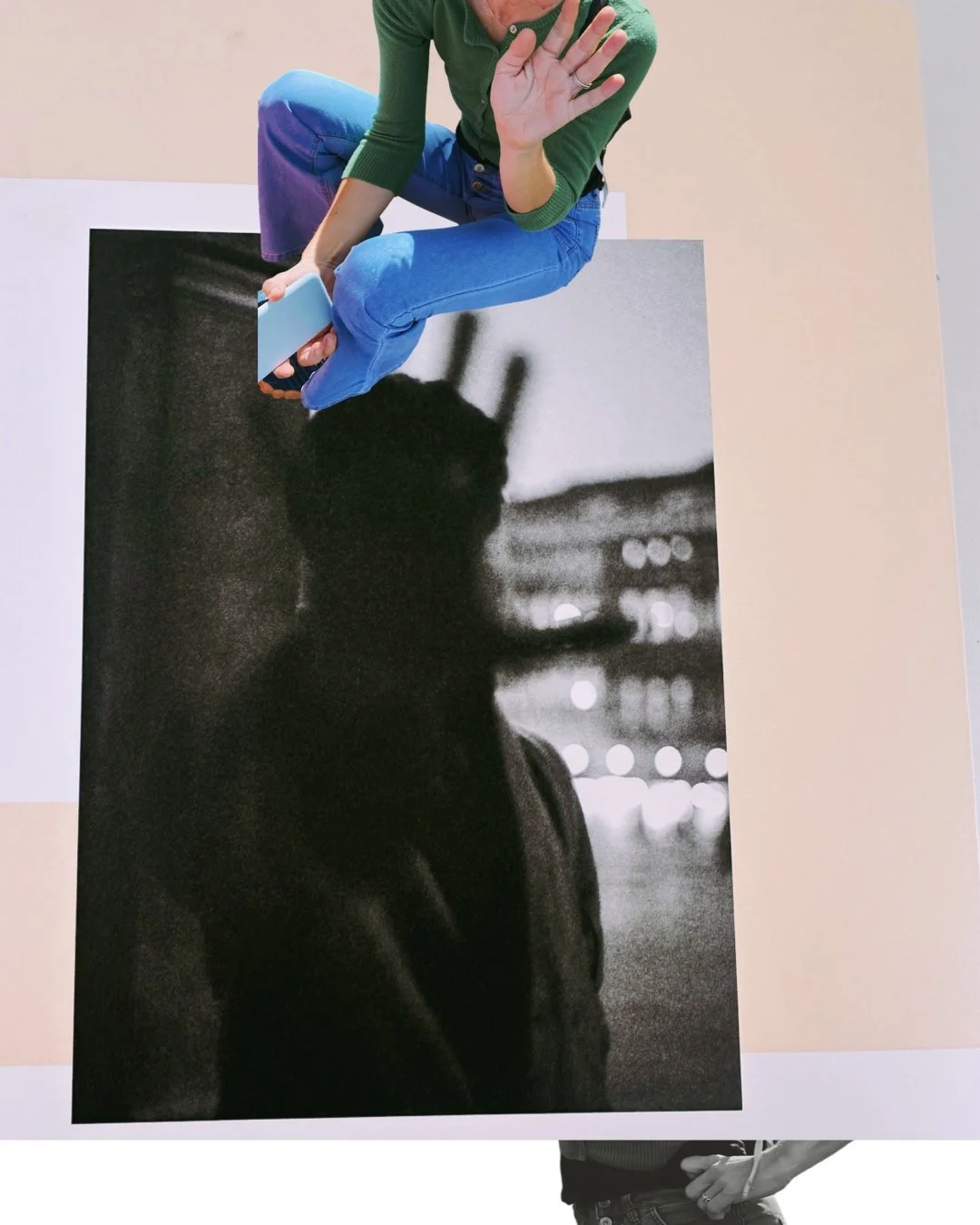

A woman spreads her fingers around in an object that no longer exists: The Invisible Object, a structure by Alberto Giacometti.

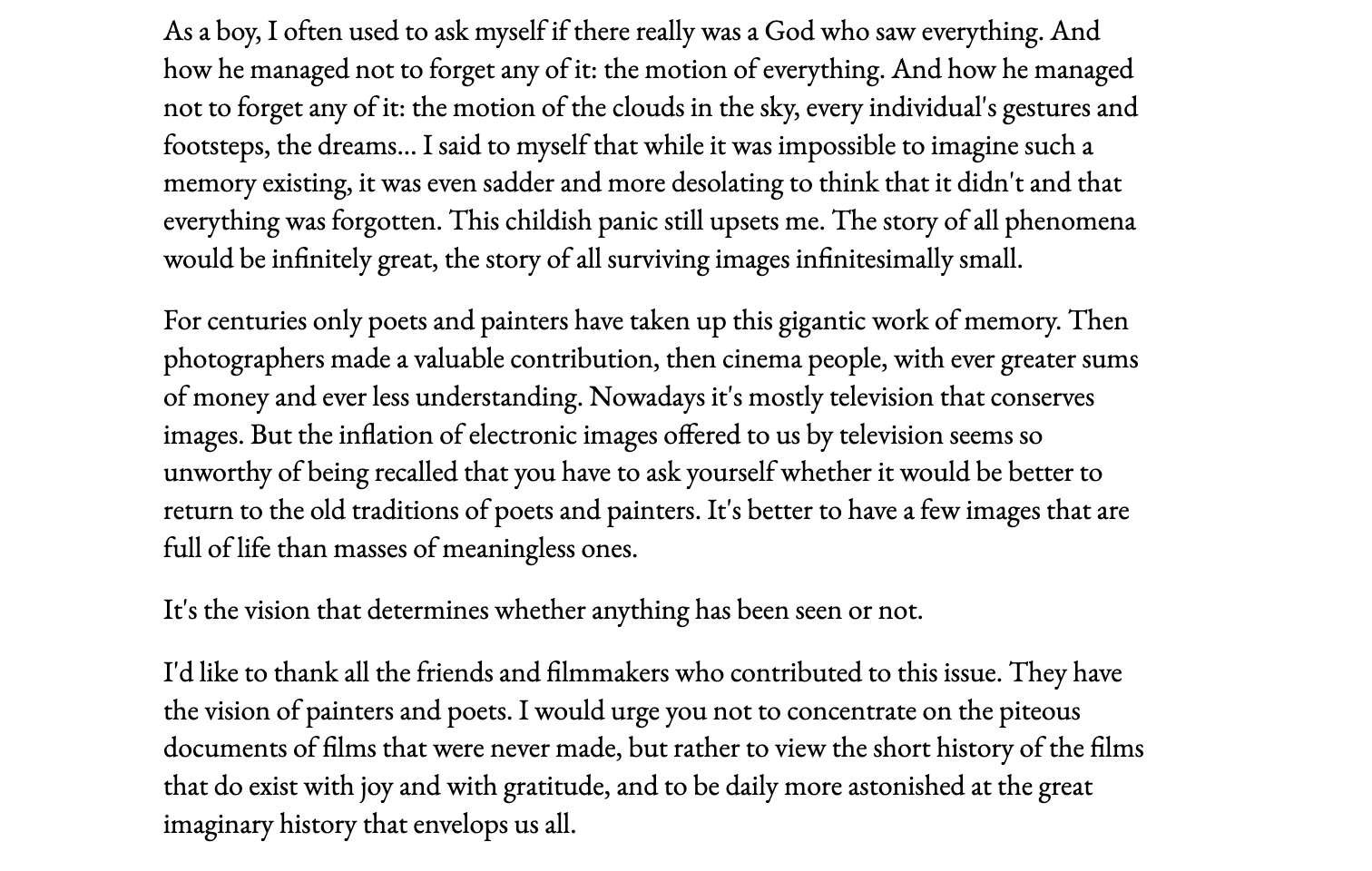

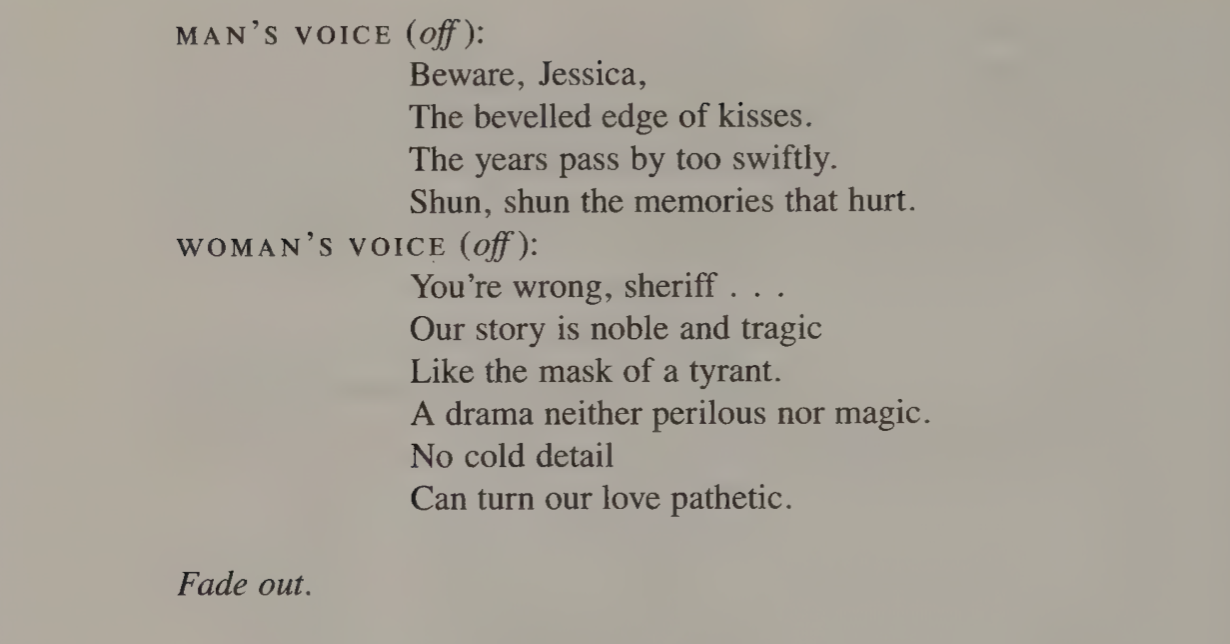

— Henri Lefebvre, The Missing Pieces

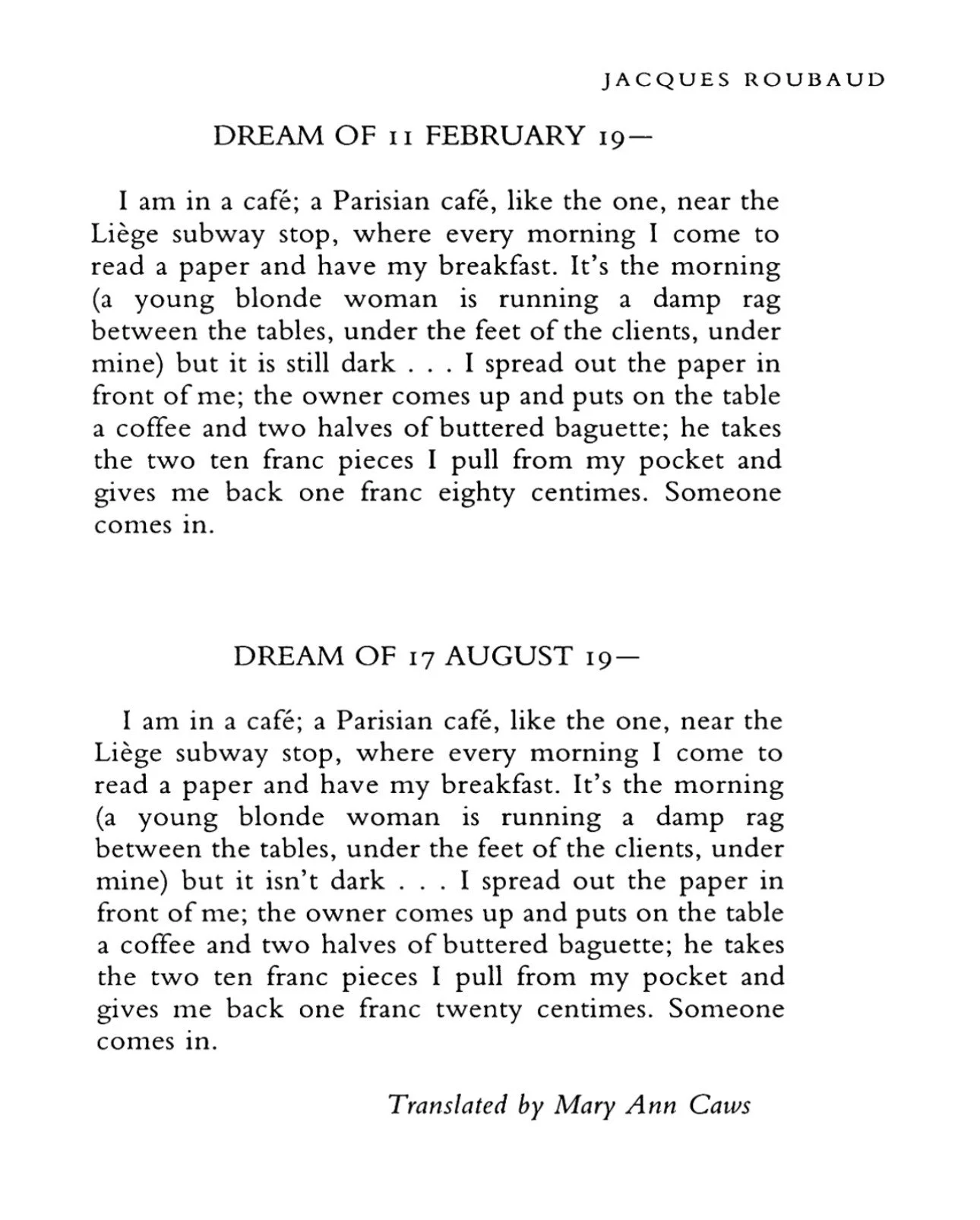

*

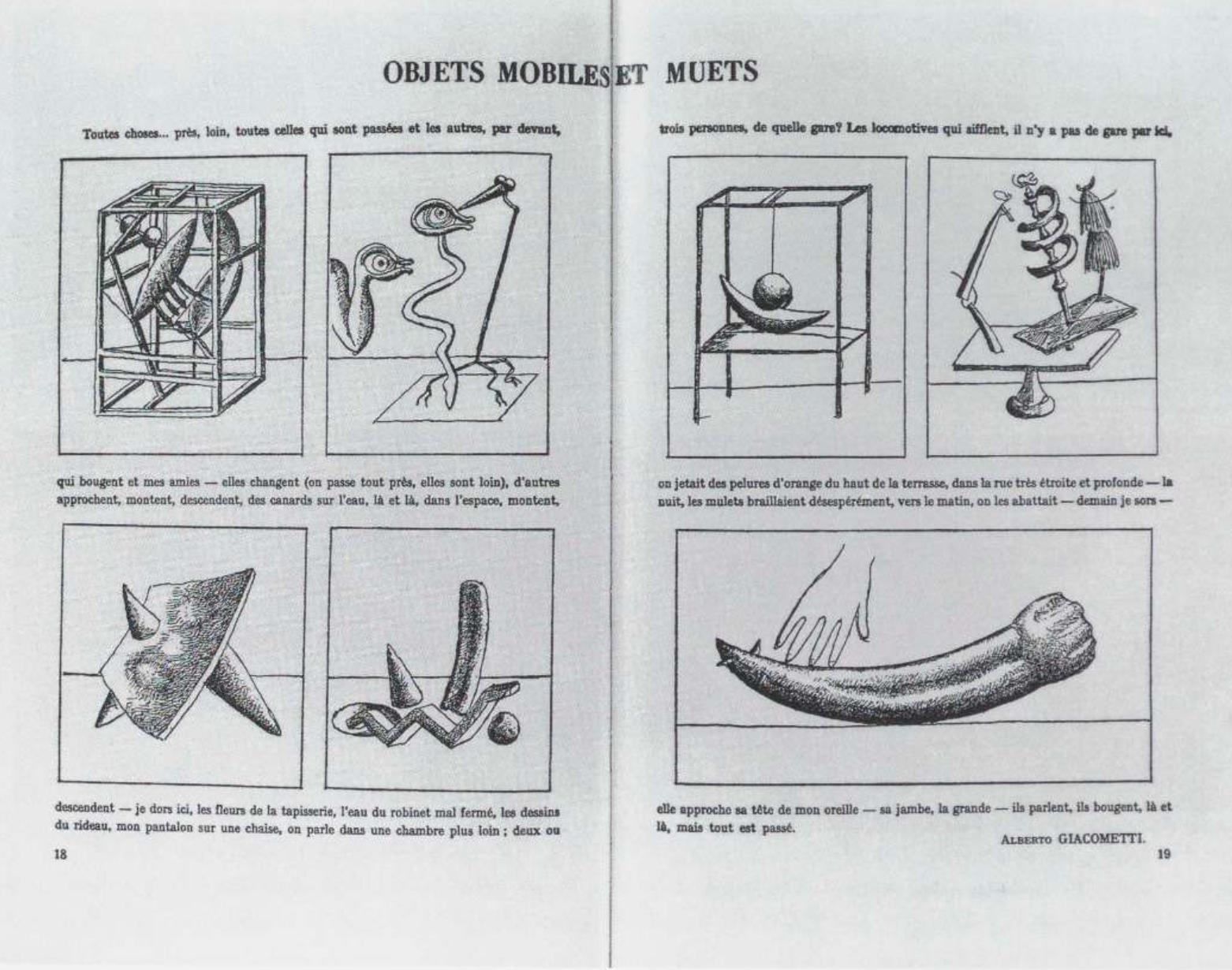

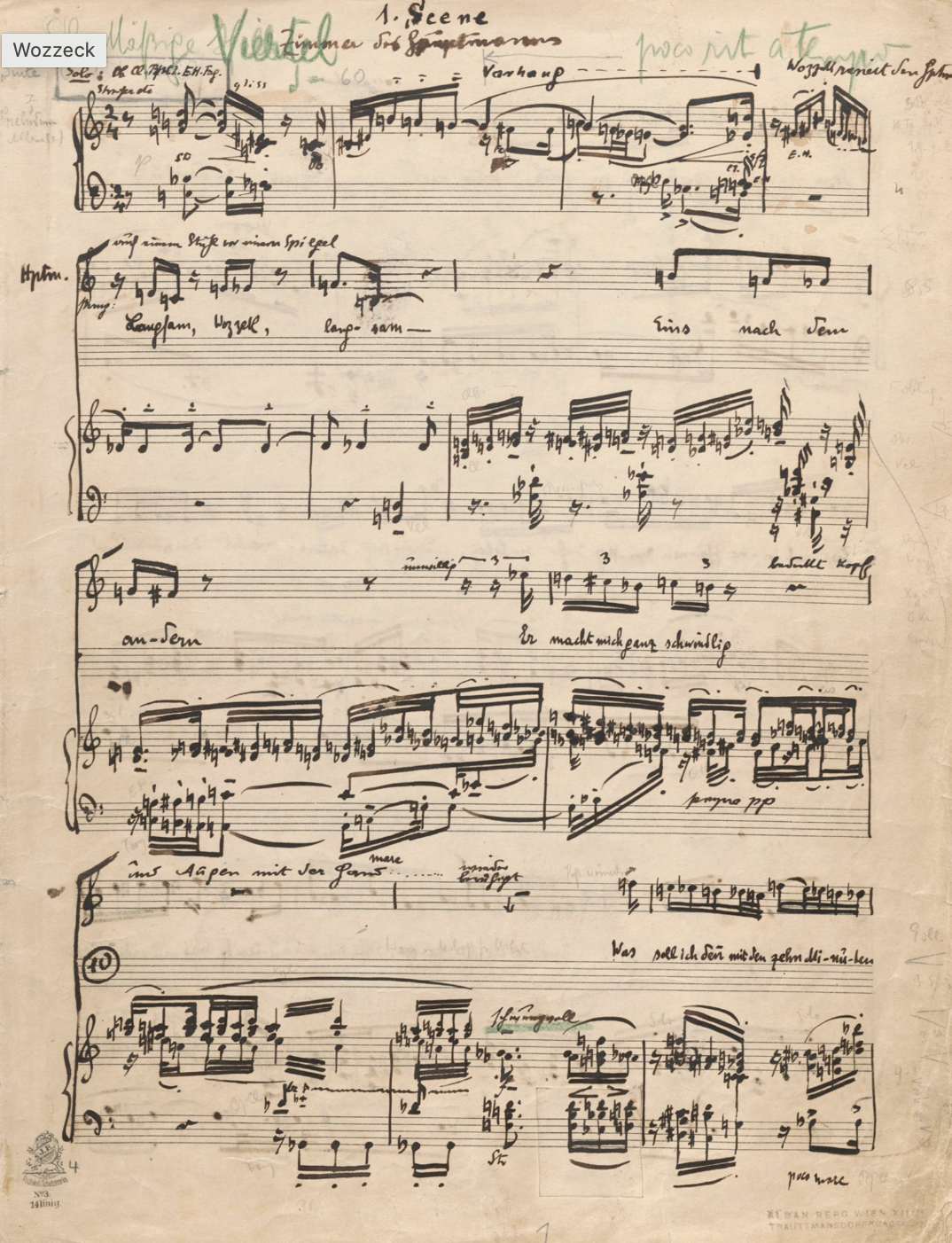

A statement on process and “copying” by Alberto Giacometti, as recorded in his Sketchbook of Interpretive Drawings —

I began to copy long before even asking myself why I did it, probably in order to give reality to my predilections, much rather this painting here than that one there, but for many years I have known that copying is the best means for making me aware of what I see, the way it happens with my own work; I can know a little about the world there, a head, a cup, or a landscape, only by copying it.

*

— intersected with my readings of Anne Carson this week. . . particularly a passage from her lecture on corners, where she mentions Giacometti’s tree right after noting that “there is something cozy” in a play by Harold Pinter, despite its “repression and menace and horrible emotions”:

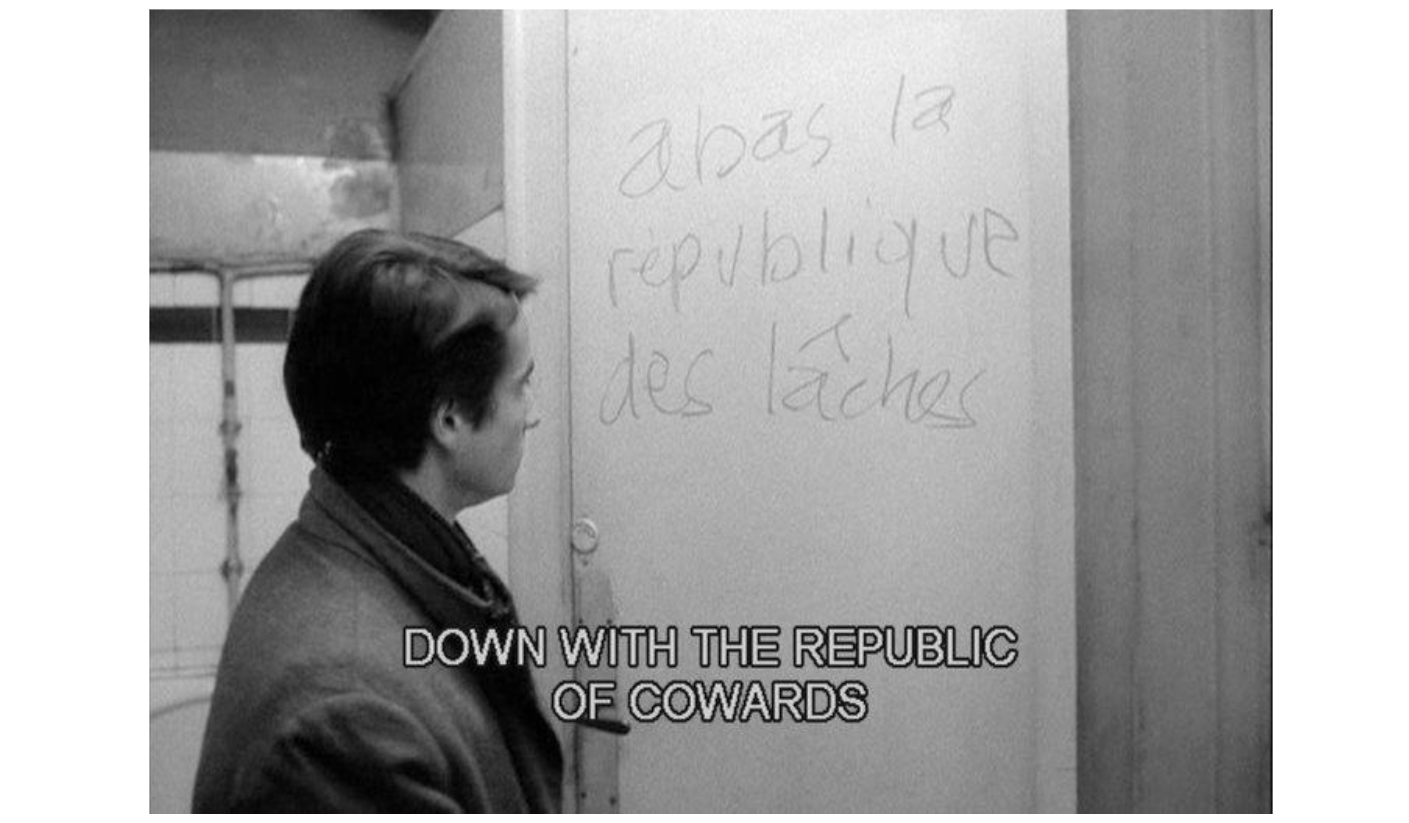

Compare a Beckett play, say, Waiting for Godot. What is so immediately desolate about Waiting for Godot as soon as the curtain rises? Maybe simply the fact that it has no house. Pinter plays generally take place in a house. Each character starts out in their little corner of the world, however ruined, psychotic, or hopeless. The stage set for the opening act of Waiting for Godot is given as an undefined place with tree. Bachelard says a house is a psychic state. Waiting for Godot offers no state. Here is no inside or outside, no structure that might open up to reveal something else. If the play contains a knowledge or opposes a riddle, it is a riddle distributed everywhere structurelessly. I wonder why he added the tree. Beckett wondered this too, eventually. In 1961, when the play was revived in Paris, he hired Giacometti to make the tree. One can see the attraction.

(audience laughing)

Well, not just the desolation and gashed surfaces and primordial manner of Giacometti's figures, there was also a sense of self-consciousness, almost despair about the limitations of their art that Beckett and Giacometti shared. Beckett wanted a tree that cried out as Giacometti did once in an interview, "I don't know if I work in order to do something "or in order to know what I can't do "when I want to do it." It's a lot to ask of a tree.

(audience laughing)

Beckett did not, at first, like the tree Giacometti made. It was reconsidered, redesigned, and remade, ending up as a straight, spindly white plaster thing that one spectator likened to a drain pipe. The tree had six leaves. In the end, Beckett called it superb. Looking at pictures of this stage set and this tree, I was reminded of something told me by a friend who is a child psychologist. When children get therapy, they're often asked to draw a picture of their house, as this is believed to be revelatory of life in the home and life in the mind. Most every kid draws the same house: a square building with central doorway, pointy roof, and chimney exuding smoke. Children of happy families draw the smoke as billowing, cloudy curves. Children of broken or difficult homes are inclined to make straight, thin smoke. Straight, thin smoke is regarded as worse, more depressing than no smoke at all or refusing to draw one's house.

(audience laughing)

When the Swiss novelist, Max Frisch, was dying, he gave a final interview in which he described a dream he kept having. In the dream, he sees Max Frisch balanced on the curve of the earth, but starting to slide off. An empty stage with white plaster tree gives just enough curve to the earth, just enough boundary to the unbounded to suggest the beginning of real terror. The unbounded, in Greek, apeiron, a word formed by adding the negative prefix alpha to the noun peirar, which is thought to mean rope end. Unboundedness is a rope not tied off at the end to prevent its unraveling. The first person to use this word as a metaphysical value, the philosopher, Anaximander, described to apeiron as the arche of all things. Arche meaning origin, first cause, first principle or beginning. And in Aristotle's account, the unbounded is abhorrent because it is nothing but beginning. Aristotle says, “Nature flees from the unbounded.” The unbounded is imperfect or incomplete, “and nature always seek completion.” Corners, part three. So on the one hand, we might regard corners as shelter, comfort, containment, completion, what Stevie Smith calls four walls and a pot of jam, something valued for their boundaries and useful in their form. On the other hand, the phrase to be cornered can signify a wish to escape or dissolve or deny the threat of angles closing.

*

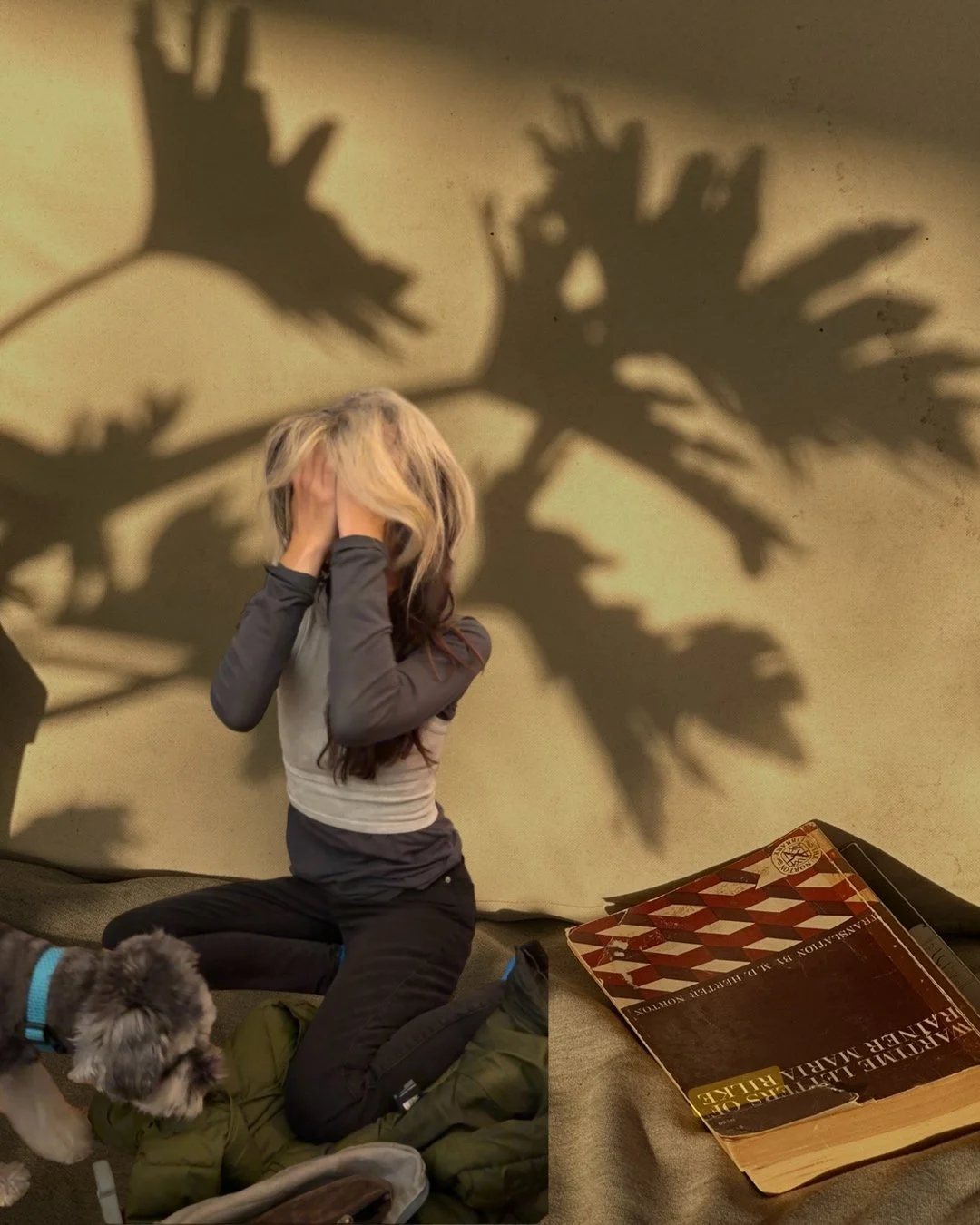

— which then rubbed up against an ekphrasis by William Carlos Williams:

A Matisse

On the french grass, in that room on Fifth Ave., lay that woman who had never seen my own poor land. The dust and noise of Paris had fallen from her with the dress and underwear and shoes and stockings which she had just put aside to lie bathing in the sun. So too she lay in the sunlight of the man's easy attention. His eye and the sun had made day over her. She gave herself to them both for there was nothing to be told. Nothing is to be told to the sun at noonday. A violet clump before her belly mentioned that it was spring. A locomotive could be heard whistling beyond the hill.

There was nothing to be told. Her body was neither classic nor whatever it might be supposed. There she lay and her curving torso and thighs were close upon the grass and violets.

So he painted her. The sun had entered his head in the color of sprays of flaming palm leaves. They had been walking for an hour or so after leaving the train. They were hot. She had chosen the place to rest and he had painted her resting, with interest in the place she had chosen.

It had been a lovely day in the air.—What pleasant women are these girls of ours! When they have worn clothes and take them off it is with an effect of having performed a small duty. They return to the sun with a gesture of accomplishment.—Here she lay in this spot today not like Diana or Aphrodite but with better proof than they of regard for the place she was in. She rested and he painted her.

It was the first of summer. Bare as was his mind of interest in anything save the fullness of his knowledge, into which her simple body entered as into the eye of the sun himself, so he painted her. So she came to America.

No man in my country has seen a woman naked and painted her as if he knew anything except that she was naked. No woman in my country is naked except at night.

In the french sun, on the french grass, in a room on Fifth Ave., a french girl lies and smiles at the sun without seeing us.

*

— which resisted the image of his infamous plums, or made me consider a counterpoint to this image, also authored by William Carlos Williams:

*

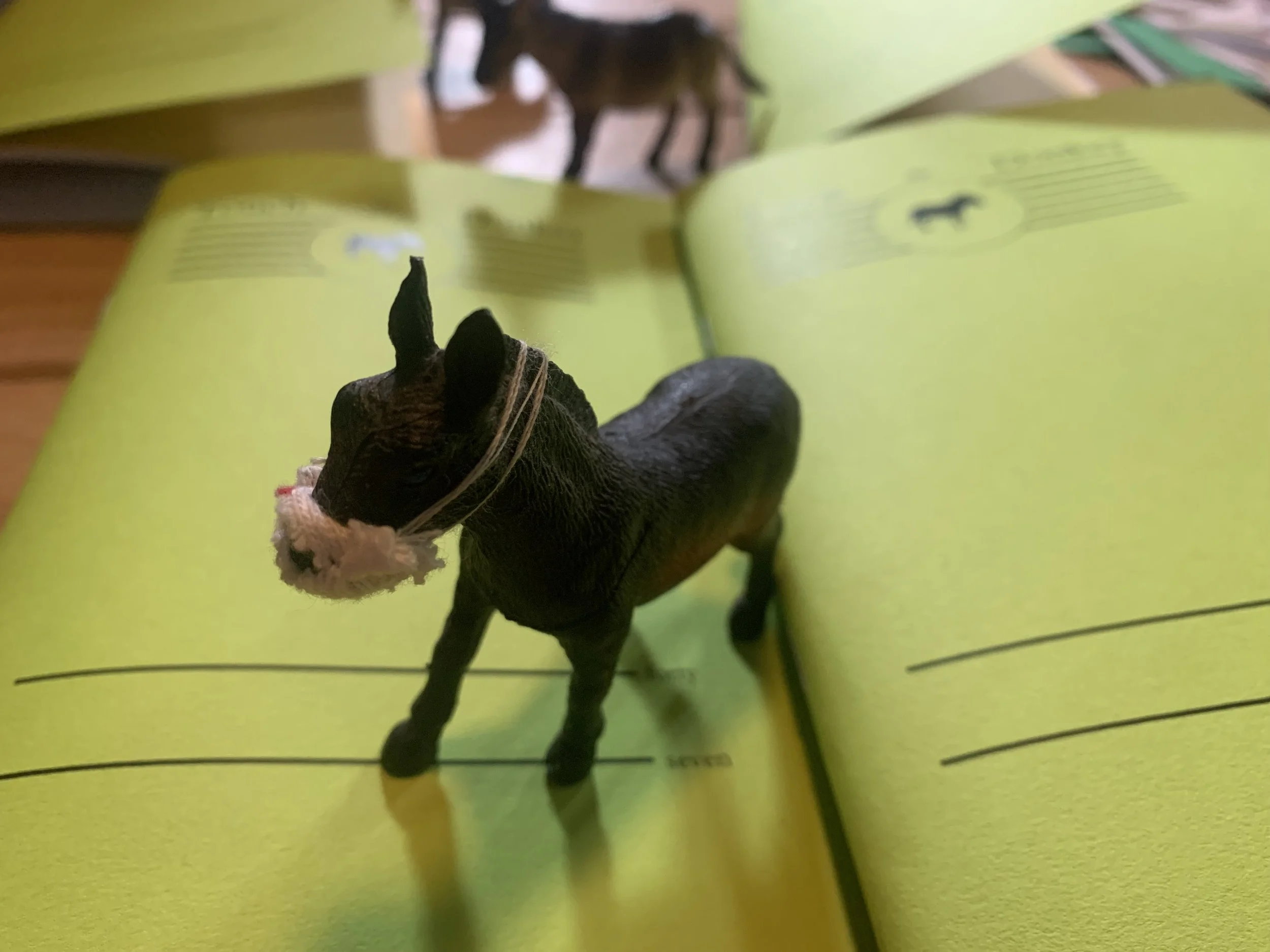

— which carried the final ellipsis into a structure resembling an ear, where the lobe had to be a hand, as imagined by Meret Oppenheim in this portrait of Giacometti’s ear:

Meret Oppenheim, The ear of Giacometti (1970-1979)

*

— which then wiggled into an “experience” written by Alberto Giacometti, himself, in “The Dream, the Sphinx, and the Death of T,” translated by Barbara Wright:

I had just experienced, in reverse, what I had felt a few months earlier about living people. At that time I was beginning to see heads in the void, in the space surrounding them. The first time I became aware that as I looked at a head it became fixed, immobilized forever in that single instant, I trembled with fear as I had never trembled in my whole life, and a cold sweat ran down my back.

*

— which then ushered me back, in a cool sweat, to the woman spreading her fingers around in an object that no longer exists, an object named The Invisible Object, a structure that relates in its absence to Giacometti.

*

Alberto Giacometti, “The Dream, the Sphinx, and the Death of T” t. by Barbara Wright (Grand Street)

Anne Carson, “On Corners” (lecture transcript)

Eric Dolphy, “Feathers”

Meret Oppenheim, The ear of Giacometti (1970-1979)

William Carlos Williams, The Collected Poems: Volume I, 1909-1939 (New Directions)

Alberto Giacometti, Small bust on a double pedestal, 1940-45