Humiliation.

Unremitting shame. This is what Ivan experiences as his heartbeat slows to a wallow, “leaving between beats an abyss of emptiness in his being, an emptiness he felt he was falling through.”

Immobilized in his own bed after waking from a nightmare that ejected him onto a city street with a flaming erection, buck naked, Ivan feels slightly “exhilarated” by this new state. He realizes his eyes are wide open, his body inaccessible to his mind. As Josip Novakovich tells it:

There was something coldly solemn about it, something extraordinary, a mysterium tremendum, something dangerous. Now instead of despising himself, he began to pity himself. Through pity he rose to the heights of respecting himself, nay, loving himself. He continued breathing involuntarily, as though somebody else were doing it.

Ivan experiences his existence without shame. He is shameless. Unfortunately, he is also dead. From here on out, the story will be narrated by Ivan's corpse, as if from inside the coffin, but also in a continuing relationship to the world, his daughters, his wife, the afterlives of love and longing.

The shadow of other shames.

In an earlier scene subtitled, “The Joys of Cuckolding Come to a Sorry End,” there is a moment when Ivan enters his office, and the staging as well as the affects seem to replay a scene from Gogol’s Nose, or else the drift of an overcoat…

Rewind to the staging of humiliation.

I keep returning to the way Novakovich builds into that moment of overwhelming shame that coincides with the subject’s death. A play-by-play of the staging.

To note, first, the sensory details indicating the ticking of time . . .

The Japanese alarm clock emitted a hiss as minutes rolled over each other. Ivan looked at the fluorescing green digits: 1:10, 1:11.

Followed by two brief sentences that locate duration within human flesh:

His wife began to snore. Then she stopped.

Immediately connected to a physical and mental experience of panic and terror for Ivan:

All of a sudden the terror of death pierced through his skin, infusing itself into his blood like cobra's poison. He smelled the incense of death, an acrid sensation in his nostrils. He remembered all the burials that he had ever seen, now unified into a single one: his own. He saw himself in a coffin, in a black suit, with his purple head propped up, giving him a permanently thoughtful air as becomes someone who is contemplat- ing being and nothingness. And he felt pangs of shame, shame which stank of old socks and genitals.

He was terrified that he would die, just suddenly vanish, without having done any- thing significant in his life, without understanding anything. He had not even had a single thought in the course of his life that could satisfy him aesthetically and fill his soul—if he had one. He had experienced only petty worries and vanity.

Followed by the usual existential dilemmas (which draw Ivan into an interesting relationship with his own subjectivity, or the character he makes of himself):

Now out of an additional vanity, out of wishing that he could think well of himself, he was worried that he had lived vainly.

In empty darkness, all his misery fell upon him. His hairs stood up on his arms and legs. His falling naked onto the pavement amidst a roar of laughter recreated itself in his head fluorescently, through a pinkish tint, with derisive echoes recalling his childhood humiliation: his head being whacked against the cement, children jeering.

Landing in the memory of childhood humiliation, or the return to that feeling of helplessness which destabilizes Ivan’s sense of himself as a husband, father, and employee.

The humiliation of death.

Ivan is dead— but the world keeps moving around him. In the section titled “A Death Certificate Speaks Up,” Ivan’s wife, Slava, calls the physician after discovering Ivan’s motionless body. Unable to reach a doctor by phone, she runs to the local pub in search of the doctor. This is where she finds him, at the tavern.

The doctor was there— a cigarette dangling from his lips, cards in his hands, a bottle of yellowish plum brandy on the table-surrounded by several yellow drunks and a blue policeman.

The doctor was clearly ill suited for his profession, good for nothing except the tavern. He had passed his university exams with the lowest passable grades; he had taken more than a decade to get his degree since his interests lay in whatever taverns were about: drinking, cards, women, and, now and then, a brawl—-though less and less frequently with his advancing age. But for that, he whored more and more routinely now at the spas

The doctor certifies Ivan’s death. And then, an uncanny sexual event begins between the doctor and the newly-widowed Slava, while her husband’s corpse sits on the bed.

Novakovich makes exquisite use of framing here: he repeats certain phrases and words to indicate a similarity between Ivan’s experience of death and Slava’s experience of ecstasy, beginning with the word “Suddenly.” So the doctor is doing his regular thing when:

Suddenly he seemed to wake up from his routine performance, for he was very sensitive to female warmth. Under the guise of further solace, while saying, “Everything's gonna be all right, he began to touch her neck and press her against his body.

And the next paragraph begins with that evocation of the delirium in mysterium tremendum:

In her near delirium, Slava hadn't paid any attention at first to the doctor's reassurances. The shivers of fear began to mix with some warm streams. She leaned her head quite freely on the physician's chest, and he began to rub his stubbly cheek against her hair, making her scalp shiver. He slid his hands down her back. “Everything's gonna be fine,” he said in his mesmerizing baritone. He buzzed these words into her ears, the warmth of his breath sending a stream of fire into the base of her brain, so that she lost her senses momentarily. The doctor pressed his fingers into her flesh beneath her skirt, sliding his palms up the back of her cool thighs.

Slava began to sigh, gasp, and moan. The doctor pressed her against the table, and she sat right on the crumpling death certificate, which rustled most disapprovingly. The doctor slid her skirt up, and with his hand kneaded her thighs and sent his pre- penile emissaries, his fingers, further into the foreign terrain. His fingers teased Slava, manipulating her electricity. She moaned as if she were falling through an abyss. The doctor kissed her and reached to unzip his pant.

“As if she were falling through an abyss.”

Ritual redress.

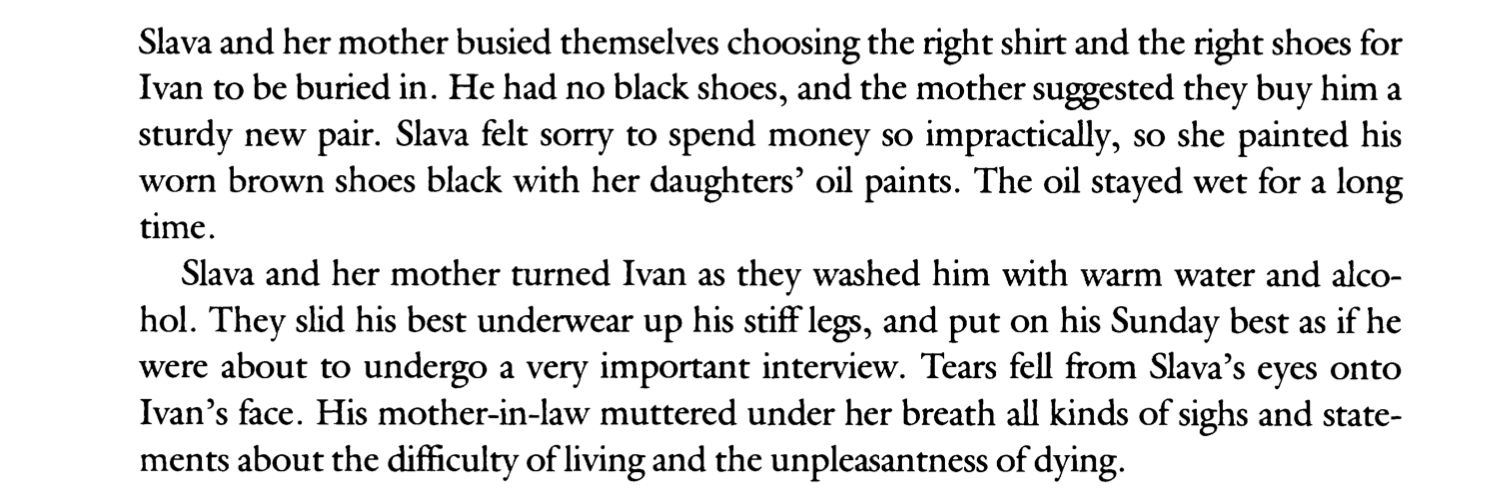

Slava must prepare Ivan for burial. She must dress him for the final time, while also addressing his physical body intimately.

As a verb, “redress” means to remedy or set right.

In its noun form, “redress” indicates a remedy or compensation for a wrong or a grievance.

When ending her two-year affair with Jean Mounet-Sully, Sarah Bernhardt blamed herself. “Dear Jean,” wrote Sarah, you must realize that I am not made for happiness.” Being so made, or not-made, Bernhardt continued to list her limitations: “It is not my fault that I am constantly in search of new sensations, new emotions. That is how I shall be until my life is worn away. I am just as unsatisfied the morning after as I am the night before. My heart demands more excitement than anyone can give it. My frail body is exhausted by the act of love. Never is it the love I dream of.” I suspect this is how every writer feels about the book they are writing, or the book they have finished, or the manuscript in progress.

I keep wondering what I owe my words in terms of life, or living in the readings of others—- and then distracting myself with the stories of others. . . . Novakovich’s next subtitle, “Messages from the Galaxy of the Dead,” indicates that we will be hearing from Ivan in his posthumous version. Panic seems to be a condition of the dead as well as the living. Ivan’s body is laid out on the table, dressed for the funeral:

Slava and his daughters came to see him. "Daddy is asleep, and won’t wake up anymore," said Slava.

The daughters shrieked.

Ivan was happy. They love me! he thought. Who would have suspect But his enthusiasm slackened as, against his will, he thought that they screamed out of fright— not because of losing him. You can feel the terrifying reality of death when somebody close dies— not necessarily somebody you love but somebody you are used to as a part of your experience. When a part of your experience vanishes from life (to become nothing), you feel that just as that part of your experience vanishes, the totality of your experience— you yourself— will vanish into nothingness. So the daughters may have screamed for themselves.

Ivan tries to interpret the responses of loved ones in a manner that satisfies the hunger for love and recognition that marked him as a child. He wanders towards the naturalization fallacy in an effort to dignify the unthinkable position in which he finds himself.

Friends come to pay their respects. His brother gets into an argument with a friend he knew well in his younger years. The two men begin throwing insults at one another: “Ustasha Croat pig!” “Serb chetnik!” Novakovich gives us the fracture of his own life in the absurd antics near the corpse. “The two childhood friends reverted to childhood and broke into a fist fight, cutting their lips and knocking out porcelain tooth caps, which they then, in a temporary truce, looked for on all fours in the floor cracks.”

The problem of narration hesitates at this edge of the impossible situation Novakovich elected to depict. We are in Ivan’s head but also in the world that refuses the existence of Ivan’s head, or of Ivan. As with life, perhaps, in death, Ivan seeks to be understood.

The wood creaked in various frequencies. Many people gathered in the room, whispering. The hissing of the whispers terrified Ivan, as if a giant octopus's limbs were engulfing him. Some whispers were not whispers, since some people were incapable of whispering. “When did he die? How?”

The corpse named Ivan observes this moment in which some of the main characters involved in his life are gathered to observe the event of his death. He listens: because he cannot respond or speak. He is condemned, as it were, to listening.

Again, he thinks back to childhood:

He thought that around him, out of respect for death, the visitors wouldn't say anything embarrassing—- and honest—- about him. Too bad I can't hear what they really think. Still, aren't I lucky? Most men after dying couldn't hear their wives and daughters cry for them— either for love or terror. And I've heard mine.

Ivan recalled his childhood daydreams about how it would be if he died right then, how sorry his friends would feel for him. He had thought that suicide was worth committing just in order to elicit compassion in his friends, to show him how much they had really loved him. The desire for suicide stemmed from a vague impression that after death you could be present at a gathering of your lamenting friends, at least present through their sorrow, which would lift you into the comforting and succoring oceanic infinity. If you knew that you would be missed among the living, life would become meaningful and lovable, and so would death.

Even as a boy, though, Ivan had known that that line of thought was grounded in bad faith. You'd have to experience it to know.

And now Ivan did experience, and he believed. Even if people didn't talk about him right now, hadn't they organized a party because of him? It was fantastic. Paradisiacal! His life was worth living just for this moment.

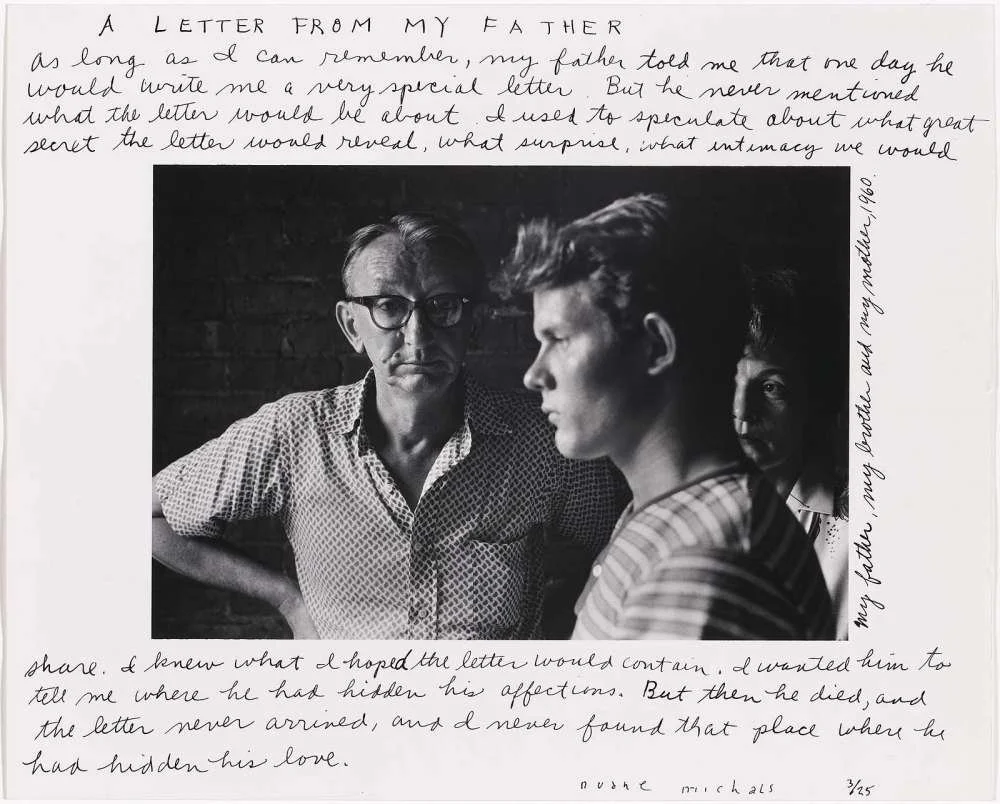

I suspect we never get over the fathers . . . but certainly, the fantastic is central to Novakovich’s prose and the stories he tells about the eastern europe that ejected him and so many others.

“As to the fourth method—that of interesting—it also is frequently confused with art. One often hears it said, not only of a poem, a novel, or a picture, but even of a musical work, that it is interesting. What does this mean? To speak of an interesting work of art means either that we receive from a work of art information new to us, or that the work is not fully intelligible and that little by little, and with effort, we arrive at its meaning and experience a certain pleasure in this process of guessing it. In neither case has the interest anything in common with artistic impression. Art aims at infecting people with feelings experienced by the artist. But the mental effort necessary to enable the spectator, listener, or reader to assimilate the new information contained in the work, or to guess the puzzles propounded, by distracting him hinders the infection. And therefore the interestingness of a work not only has nothing to do with its excellence as a work of art, but rather hinders than assists artistic impression.”

— Leo Tolstoy on “interestingness” as a barrier (can’t say I agree with him at all on this)

*

Duane Michaels, A Letter From My Father

Josip Novakovich, “Subterreanean Fugue” (PDF)

Morphine, “Hanging on a Curtain”

Morphine, “Swing It Low”