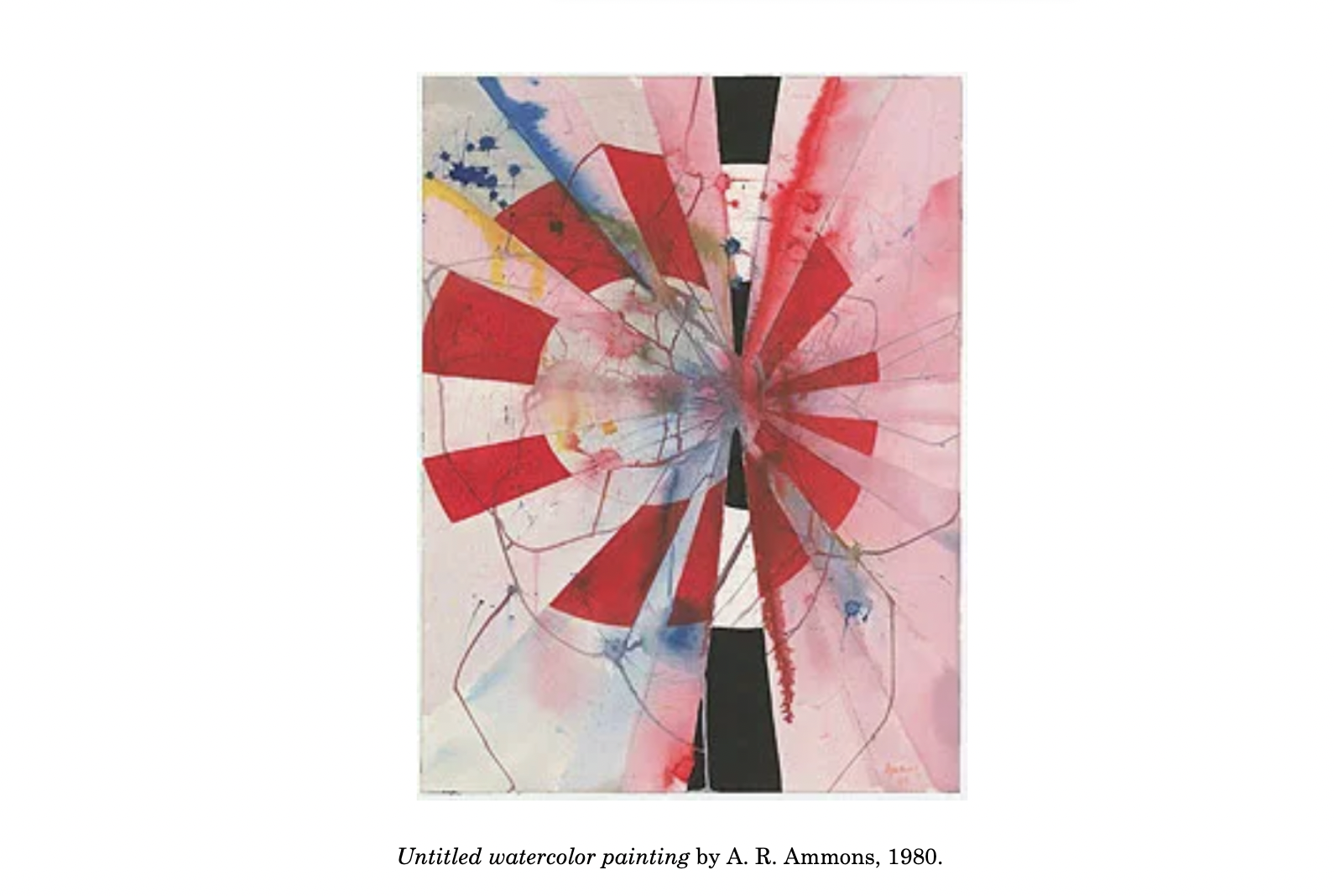

I think true poets are often in flight from their poetry, and it is only when they become fairly heroic that they can stand and look their own poetry and their own self in the face, because most of the big poets we know are monsters.

– A. R. Ammons

. . . multiplying defenses does nothing to mitigate defensiveness.

— Oliver Davis and Tim Dean

And the noise is as much as I can bear.

— P. J. Harvey

1 . . . true poets in flight . . .

And there is a poem in the stone, as there have been poems on the faces of stone from the earliest days of language.

The poem seeks a shape for saying something about what it means to live, to be a creature made and unmade by language, identified by words, chastised in verbs, lost in the “black wells of possibility” that A. R. Ammons will reference if you continue reading…

Poetics

I look for the way

things will turn

out spiraling from a center,

the shape

things will take to come forth in

so that the birch tree white

touched black at branches

will stand out

wind-glittering

totally its apparent self:

I look for the forms

things want to come as

from what black wells of possibility,

how a thing will

unfold:

not the shape on paper — though

that, too — but the

uninterfering means on paper:

not so much looking for the shape

as being available

to any shape that may be

summoning itself

through me

from the self not mine but ours.

A. R. Ammons

A shape is not quite a ‘form’, or should not be collapsed into the idea of form . . . it seems.

2 . . . become fairly heroic . . .

Alas, no “little wizard” — but you can admire this little lizard instead. Take it with the scent of soap and lutes and then another poem, as spoken into text by Alice Notley in 2001, with her lecture titled “Instability in Poetry” —

3 . . . look their own poetry and their own self in the face . . .

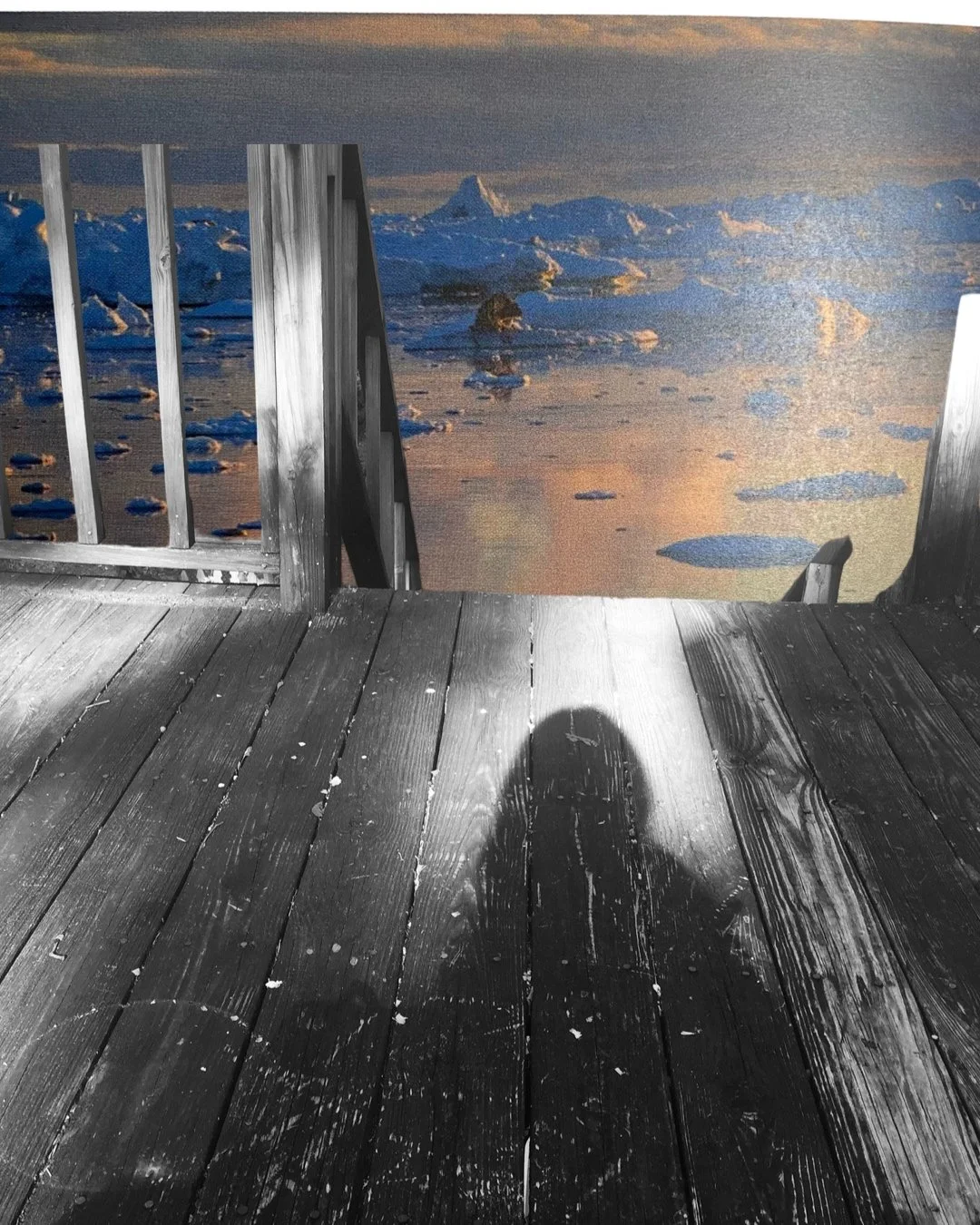

Your hair is scattered light:

the Greeks will bind it with petals.

— H. D., “Chorus to Iphageneia”

Staring at my mother’s Antartica from the back porch, living in multiple lands and temporalities: the poet’s station is quantum. The place is somewhere between the islets and the stanzas: the how of the poem meets the hows of the house in the scaffolds of syntax. Nazim Hikmet’s poem, “On Living,” buries its song beneath the form of an utterance when the line breaks are abandoned . . . . as if to say: “I mean, you must take living so seriously that even at seventy, for example, you’ll plant olive trees – and not for your children, either, but because although you fear death you don’t believe it, because living, I mean, weighs heavier.”

O, how “heavier” sounds.

How sounds lock horns with John Ashbery’s “love that is always like headlights” — how one queerly and ever-nearly hears the pen pausing on the flow chart:

Love that lasts a minute like a filter

on a faucet, love that is always like headlights in the glistening dark, heed

the pen’s screech. Do not read what is written. In time

it too shall become incoherent but for the time being it is good

just to tamper with it and be off, lest someone see you. And when this veil

of twisted creeper is parted, and the listing tundra is revealed

behind it, say why you had come to say it: the divorce. The no reason, as

the plane dives up into the sky and is lost. All that one had so carefully polished

and preserved, arranged in rows, boasted modestly to the neighbors about,

is going and there is nothing, repeat nothing, to take its place.

How the “listing tundra” lisps a little, as if to indicate the tongue limping.

The poet’s tongue must always limp a little, playing Eurydice to the beloved lyre-bearer known as the mind.

4 . . . because most of the poets . . .

How Marguerite Yourcenar wrote a testament to its abyss in L’oeuvre au noire: “Night had fallen, but without his knowing whether it was only within him or in the room: to him everything now was night. And night was also in motion: darkness gave way to more darkness. But this darkness, different from what the eyes see, quivered with colors . . .”

And the silence rang and rang and rang and rang and rang as Arthur Rimbaud invented the color of vowels from silences —

5 . . . we know are monsters . . .

The idea of pacing as applied to the velocity of curses coursing through Amy Gerstler’s "“Fuck You Poem #45”:

Fuck you puce and chartreuse.

Fuck you postmodern and prehistoric.

Fuck you under the influence of opium, codeine, laudanum and paregoric.

Fuck every real and imagined country you fancied yourself princess of.

Fuck you on feast days and fast days, below and above.

Fuck you sleepless and shaking for nineteen nights running.

Fuck you ugly and fuck you stunning.

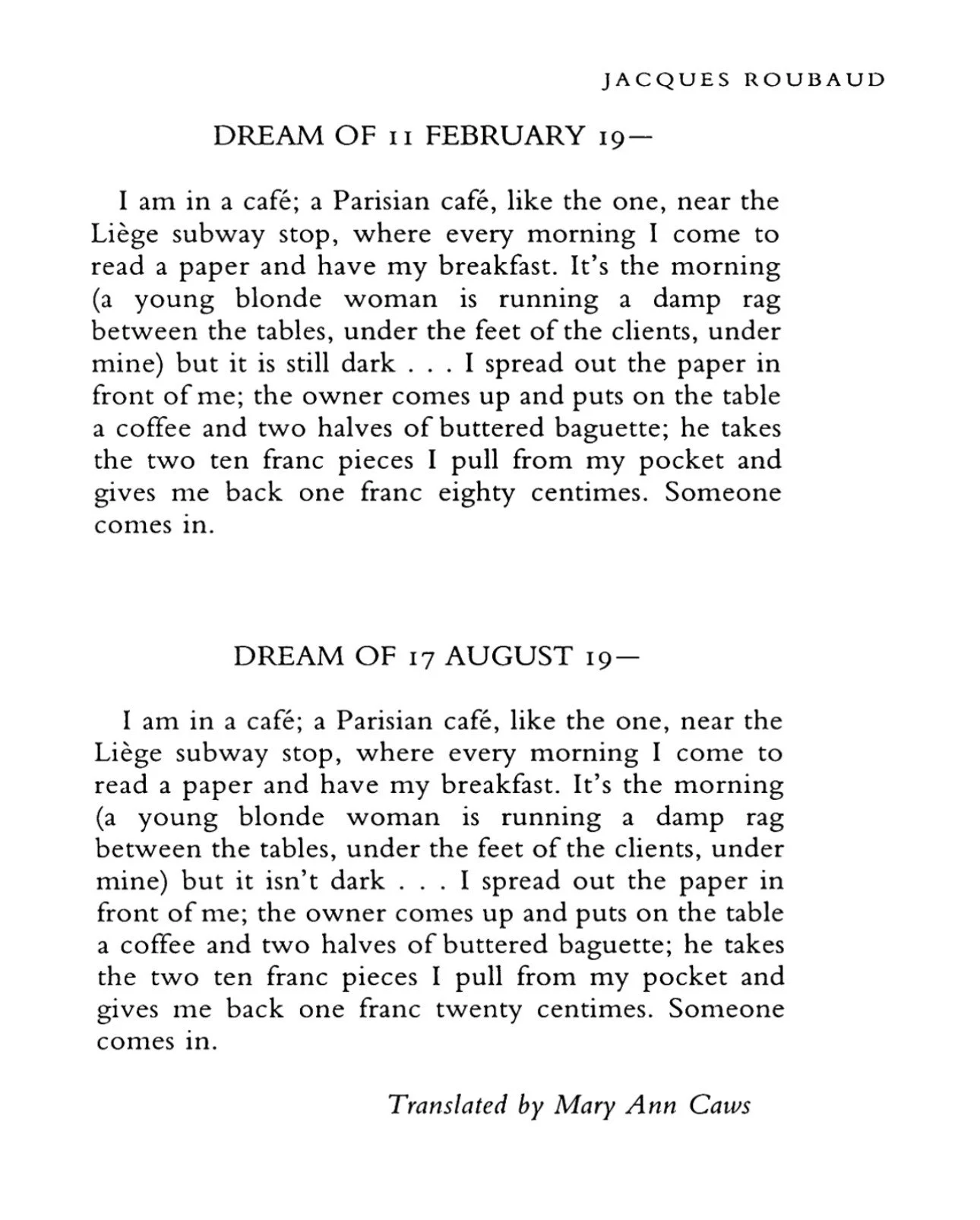

Cut to the dreams that vary barely, repetitions that differ in number of centimes, as with those of Jacques Roubaud:

O bows and bows and bows and arrows — “Someone comes in,” per Roubaud. “I am in a cafe” where everything begins.

5. . . we know our monsters . . .

How the song haunts from inside the forest, where there is a monster who has done terrible things, the monster hides in the woods and this is the song it sings: Who will love me now? Who will ever love me? And a naked young man jumps into “the scrotumtightening sea” at the beginning of James Joyce’s Ulysses. And the date was October in the year 1905, when James Joyce sent a letter to his publisher, having already struggled to find a publisher for his much-cleaner book of short stories, Dubliners, and the curse words Joyce didn’t want to edit out of the text.

“It should be noted that the allusion to the stories they tell each other is made immediately after the mention of semen dropping in humus, which, in the Aristotelian phrase revived by Roland Barthes, is a particularly clear case of the “post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy” (McQuillan 326). The reader is made to sense that ‘story time’ is going to disturb the lovers’ blissful ignorance of each other. What is more, it is exactly at the same moment that James Joyce’s words to Grant Richards, his publisher for Dubliners, are echoed: “I think people might be willing to pay for the special odor of corruption which, I hope, floats over my stories.”

And the reader of Joyce’s book is given the sense that ‘story time’ will disrupt the lovers’ blissful ignorance of each other, as it did to Paolo and Francesca.

7 . . . multiplying defenses . . .

To quote Oliver Davis and Tim Dean, from Hatred of Sex:

Group identities are no less defensive than individual ones; possibly they are more so. To claim that I have dual identities or intersecting identities, in the lingo à la mode, is simply to declare that my ego presides over various territories that it will defend against incursion. If identity denotes the ego's colonizing designs on experience, then narcissism could be redescribed as the imperialism of the psyche. Beneath contemporary claims made in the name of group identity, no matter how ostensibly progressive or radical, one hears the insistent clamor of narcissism.

Identities pose a special problem when it comes to sex because, as prototypically bound forms, they remain antipathetic to the effects of unbinding that characterize sexual pleasure at its most intense. Sex undoes identity. The contemporary shibboleth of ‘sexual identity’ is, from the psychoanalytic point of view, a contradiction in terms. One cannot credit the concepts of both the unconscious and identity; they are mutually exclusive. The psychoanalytic unconscious spells the impossibility of each and every identity. In this light our cherished identities may be redescribed as desperate defenses against the polymorphousness of pleasure, the multiplicity of desire, and above all the centrifugal forces of unbinding. Trumpism has made abundantly evident that there exist no nontoxic identity formations.

To quote Johannes Göransson from a book I devoured during pandemic:

In Socrates’ erotic anxieties about the written word, we can sense the origins of the most pervasive metaphor for translation: the idea that a translation is either ‘faithful’ or ‘free’. For many critics, the degree of a translators’ ‘fidelity’ is the only way of even discussing the translation. Translation’s proliferation of language ruins the monogamous illusion of the original.

To think that nothing gets as close as this . . .

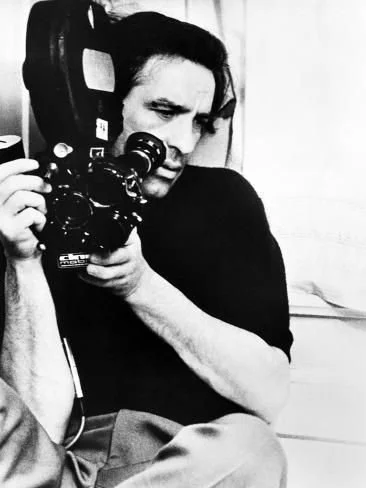

John Cassavetes during filming of Woman Under the Influence.

*

A R. Ammons, “Poetics”

Alice Notley, “Instability in Poetry” (2001 Talk given at Temple University)

Amy Gerstler, “Fuck You Poem #45”

H. D., “Chorus to Iphageneia”

Jacques Roubaud, “Two Dreams” tr. by Mary Ann Caws

Johannes Göransson, Transgressive Circulation, Essays on Translation (Noemi Press)

Marguerite Yourcenar, excerpt from The Abyss, tr. by Grace Frick

Nazim Hikmet, “On Living”

Nicole Cooley, “Poetry of Disaster”

Oliver Davis and Tim Dean, Hatred of Sex (University of Nebraska, 2022)

PJ Harvey, “Who Will Love Me Now?”

PJ Harvey, ”Sweeter Than Anything”

PJ Harvey, ”This Wicked Tongue”

PJ Harvey, “Angel”

PJ Harvey, “Stone”

PJ Harvey, “Horses In My Dreams”

Philip Fried, “A Place You Can Live: Interview with A.R. Ammons,” Terrain.org, October 22, 2009.