Art can be understood in a masked way, but at the same time it cannot be so idiosyncratic that it becomes impossible for someone to see what you have at stake.

— Kiki Smith said, reflecting on a quote from Lauren Berlant’s “Intimacy”

2

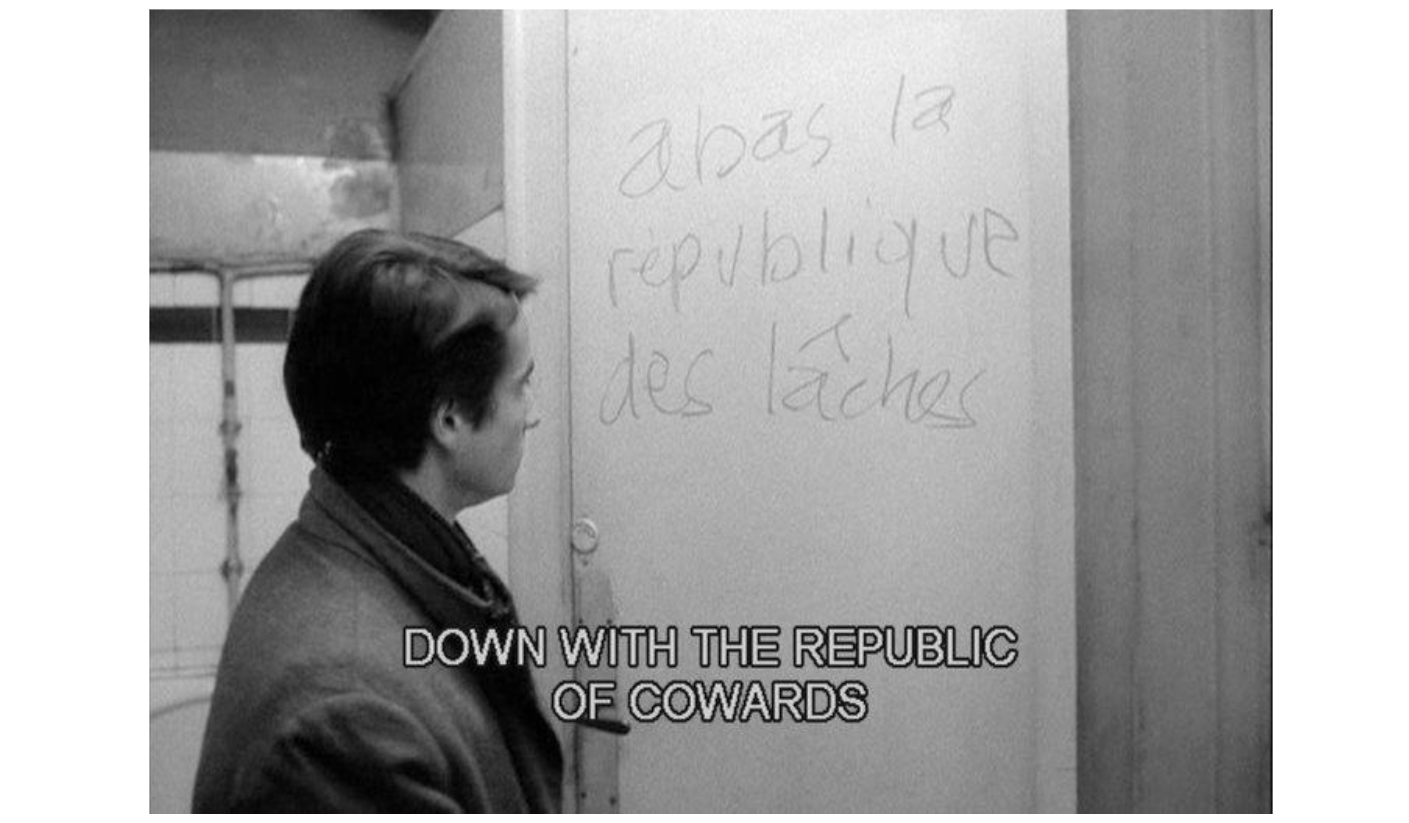

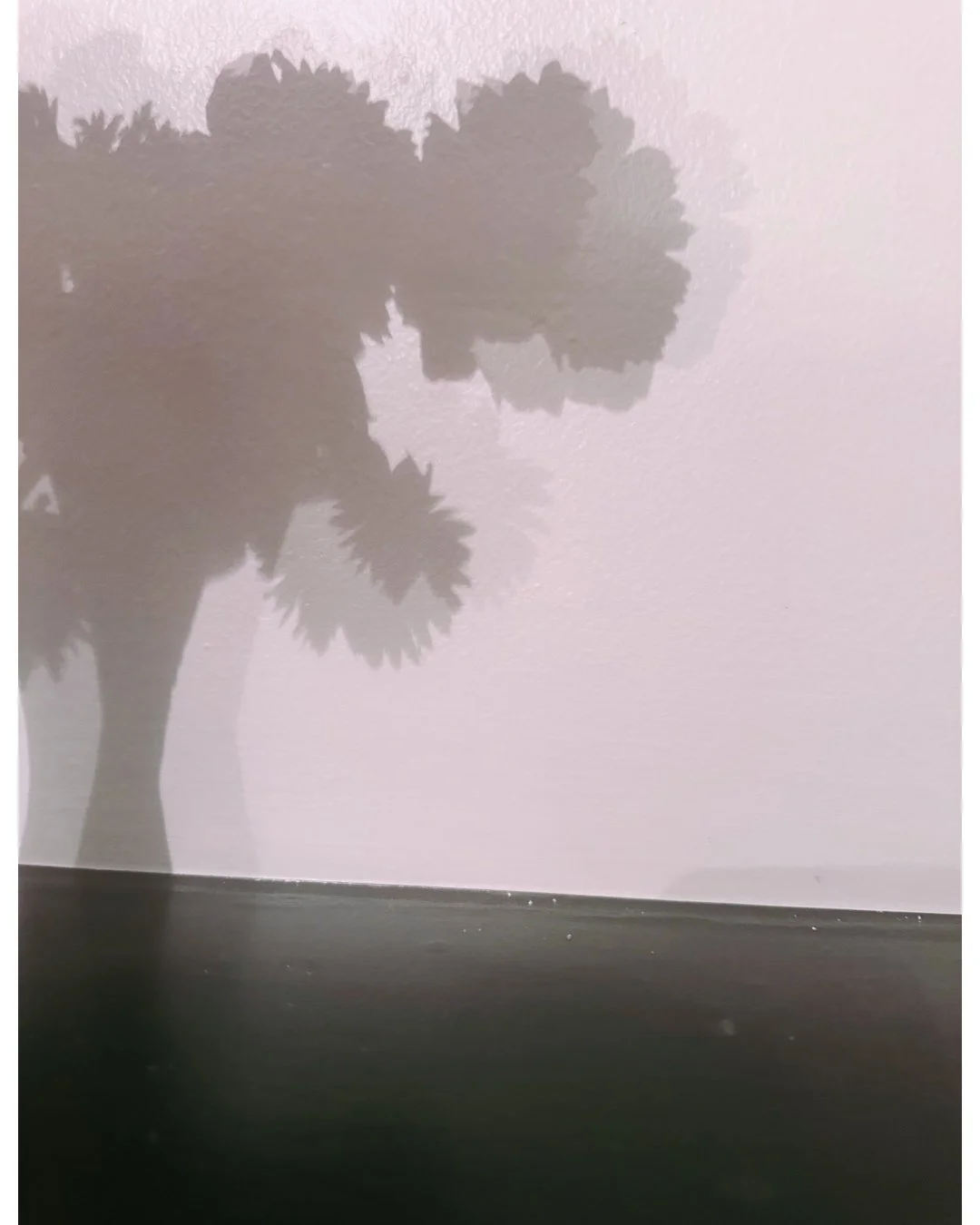

This past weekend, I spent a lot of time trying to locate the transactional self of late capitalism, as given in contemporary literature and art, only to find myself distracted by shadows on the mantle, a sidereal provoked by Svetlana Boym’s formulation of the “off modern” as a method of inquiry that engages Walter Benjamin’s reading of history against the grain. Against the grain we are given. Against the ways “into” the popular and significant. Against the speedy realm of accelerationism and profuse verbiage. Against every part of me that is tempted to fake it in order to “make it” — which is to accede to being the very thing I hate.

2.1

Having pledged my troth to self-division and diversions, I could not very well erase the sort of train passing through Peter Schjeldahl’s “Gauge,” and “the romance of the verb” in the ache of his stanzas, a disaster I bring to this screen where it may apprehend others in their relationship to trains or music or poetry or the revival of “bespeaking” amid the unforgivable beauty of hems and hemmings.

2.3

Marcel Proust’s search for lost time shapes the form of his novel. The Proustian character is estranged from the memory that re-creates him. The mind wakes up from sleep disoriented, having "lost the plan of the place where it finds itself," as Proust writes in the preface to Contre Sainte-beuve.

But being lost always occurs in relation to place.

One must be somewhere to know one is lost.

One must have something to lose.

2.4

By giving evocation a claim on our imaginations, Proust asks us to inhabit our own estrangements. strangeness. Familiar places disappear; they abandon their geographic location only to visit as a fragment we notice in the late afternoon light burnishing an empty bleacher at the high school. Like Proust in the "unknown country" of music being played at Madame Verdurin, we wonder who created this place. Who invited us inside it?

“In the work of what composer did I find myself?” wonders the Proustian narrator.

The moment of recognition relies on the first place, or the moment it recognizes: “Thus, suddenly, I recognized myself in the midst of this music that was new to me. I was in the middle of Vinteul’s Sonata.”

The lost place has been named; the name has been secured within duration through the act of localization.

Recollecting Elstir's paintings provides access to “the places where I found myself so far from the real world,” Proust tells us; he wouldn’t be startled if he bumped into a myth as he walked to the courtyard. (Does art make us more ‘receptive’ to ghosts?) The artist brings the flower into himself as Elstir's transplant, the flower “into the interior garden, where we are forced to live always.” Each person has his secret garden, but also the garden he unknowingly inhabits in the interior of others. Gilberte exists to him as the thought which appears when he imagines her “before the porch of a godly cathedral, explaining to me, the significance of the statues, and with a smile that spoke kindly of me, introducing me as her friend to Bergotte.” The first impression acquires that statuesque significance.

As for Albertine, she is “the young girl” fluttering in a group of girls at the sea resort called Balbec. She wears a beret, “her eyes intent and laughing, mysterious still, slim, like a silhouette profiled upon the wave.” This first image comes to replace the last image, or the image of the leave-taking. Humans are apprehended in the gaze which moves from exterior to hidden interiority, like a secret.

. . . .

“Proustian persons never let themselves be invoked without being accompanied by the image of sites that they have successively occupied,” wrote Georges Poulet in Proustian Space. And the sites we occupy are not limited to the sites in which we were encountered; the sites also include places where you dreamed of seeing us. These places are alive in new narrative forms. In this way, a place participates in the knowing of a person.

2.5

In baseball, “home base” refers to the home plate consisting of a rubber slab where the batter stands; it must be touched by a base runner in order to score.

In popular slang, reaching “home base” (or fourth base) refers to”'consummating the relationship by having sex, making love or fucking.”

To “finish in home base” refers to the act of “ejaculating inside your girlfriend.”

2.6

TEXT 1

“Not everything is a text, but a text is a good image for much of what we know - for everything we know that is beyond the reach of our own immediate experience, and for most of what we imagine is our immediate experience too. Literature is practice for, the practice of, such knowledge.”

2.7

HE: When you say that you don't remember fainting and losing consciousness, which part of the memory can't you recall?

ME: That memory is so overloaded that it requires a self, or acquires a selfhood, by virtue of its continued existence.

HE: Does the memory exist if you can't remember it?

ME: How could I answer that? Certainly, the expectation that such a memory exists shapes my relationship to knowability, and makes me less confident in claiming to know things about myself. If that memory exists, you are just as likely to be able to access it as I am. So it isn't my memory . . .

HE: You don't like talking about dizziness.

ME: It's not very interesting to me.

HE: Why?

ME: If I had blue eyes, they wouldn't be interesting to me either. The lack of blue eyes is what makes them intriguing. People who haven't experienced serious unrelenting vertigo bring it to the page as metaphor for a fantastic sensation they can't quite imagine. Or can't imagine entirely. We 'try on' those blue eyes. But trying on blue eyes doesn't require as much imagination when you google for affect and details. One risks less than not even bothering to imagine it.

HE: So vertigo is 'interesting'?

ME: Anything is interesting when one can choose the nature of our relation to it.

HE: What do you want the vertigo-borrower to do?

ME: I want them to be destroyed by vertigo. I want them to feel it.

HE: That is very mean.

ME: And yet, it fails to be ‘meaningful’ somehow. Much of artistic preference is interiority that projects itself onto a screen.

2.8

Walter Benjamin recounts a story from the third book of Herodotus's Histories in order to show us the “nature of true storytelling,” as distinguished from the mere recounting of information or data:

“The value of information does not survive the moment in which it was new. It lives only at that moment; it has to surrender to it completely and explain itself to it without losing any time. A story is different. It does not expend itself. It preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time.”

ME: See? A story does not expend itself.

HE: How is this related to Proust?

ME: Well, the Proustian world is obviously unstable; its topography is mapped by the mind wherein each place partakes of the same space between remembering and imagining. And each border is that of a fragment, a piece in the blurred puzzle of proximity and relationships, like that “electrical projection"“on the wall in his childhood, the magic lamp that reveals only the illuminated patch. —- So the Albertine of the past seeps continuously from the gestures of the Albertine of the present. There is the tension between her personhood and her value to the author.

2.9

Perhaps this is just a species of metaphor, as when Vladimir Nabokov fashioned himself as “the shuttlecock above the Atlantic” admiring the blues of his “private sky”— a playful figuration that resists naming the game that is being played. Badminton gave us the shuttlecock. It was popular among the leisured upper classes who made use of dachas. In this metaphor transplanted from Russian soil, Nabokov provided a means for the exile to remain “at home” in the space between homes. Diplomacy, too, is a game. And N’s diplomacy often involved to scoring points through what Adam Thirlwell called the “militant literalism” he applied to translation.

3.0

HE. But you take words too seriously.

ME. Only by taking them seriously, and with a certain melancholy, do I discover the laughter in them. Seriousness can be funny.

HE. Not funny to me.

ME: Very funny to Me, actually. Maybe not funny to He. Literature has many ways of getting around its Alberts.

Art gives you an experience that you didnʼt have before. You get to discover and experience something, even though you do the same things over and over again. Time presents itself as new at each moment, as long as we are here. It does continue, with or without us, but it has the opportunity inherent in it that our perceptions can change. We canʼt change timeʼs trajectory, but we can change our relationship to time and to everything else. We can change our minds about time and love. Time is always the same, but it can move. There is a lot of space in time.

— Kiki Smith

*

Amy Millan, “I Will Follow You Into the Dark” (cover of Death Cab for Cuties song)

Amy Millan, “Lost Compass”

Lavinia Meijer and Phillip Glass, “Night on the Balcony”

Peter Schjeldahl, “Gauge” (The Paris Review)