It takes a great deal of love to create a dead man who never dies, to listen to him and to speak to him, and find out his wishes, which he will always have because one has created him.

— Elias Canetti

You are mine own.

— the words set in Alexander von Zemlinsky’s Lyric Symphony

Helene Karoline Nahowski Berg

The opera

Although Alban Berg first glimpsed Helene Nahowski at the Vienna State Opera, their formal introduction occurred on April 19th, 1907, a date that coincided with Good Friday. Alas, the two fell in love. Helene’s father worried about Berg’s physical health and asthma and maintained a firm opposition to their marrying until 1911, when he finally relented and allowed his daughter to marry the man she adored. To Helene, Alban was perfect, ideal—- his physical challenges and nervous ailments didn’t bother her. His daughter from a previous relationship was welcomed with love. She jettisoned her burgeoning career as an opera singer in order to focus on Alban’s career as a composer. This sort of tragedy wasn’t unusual in Vienna.

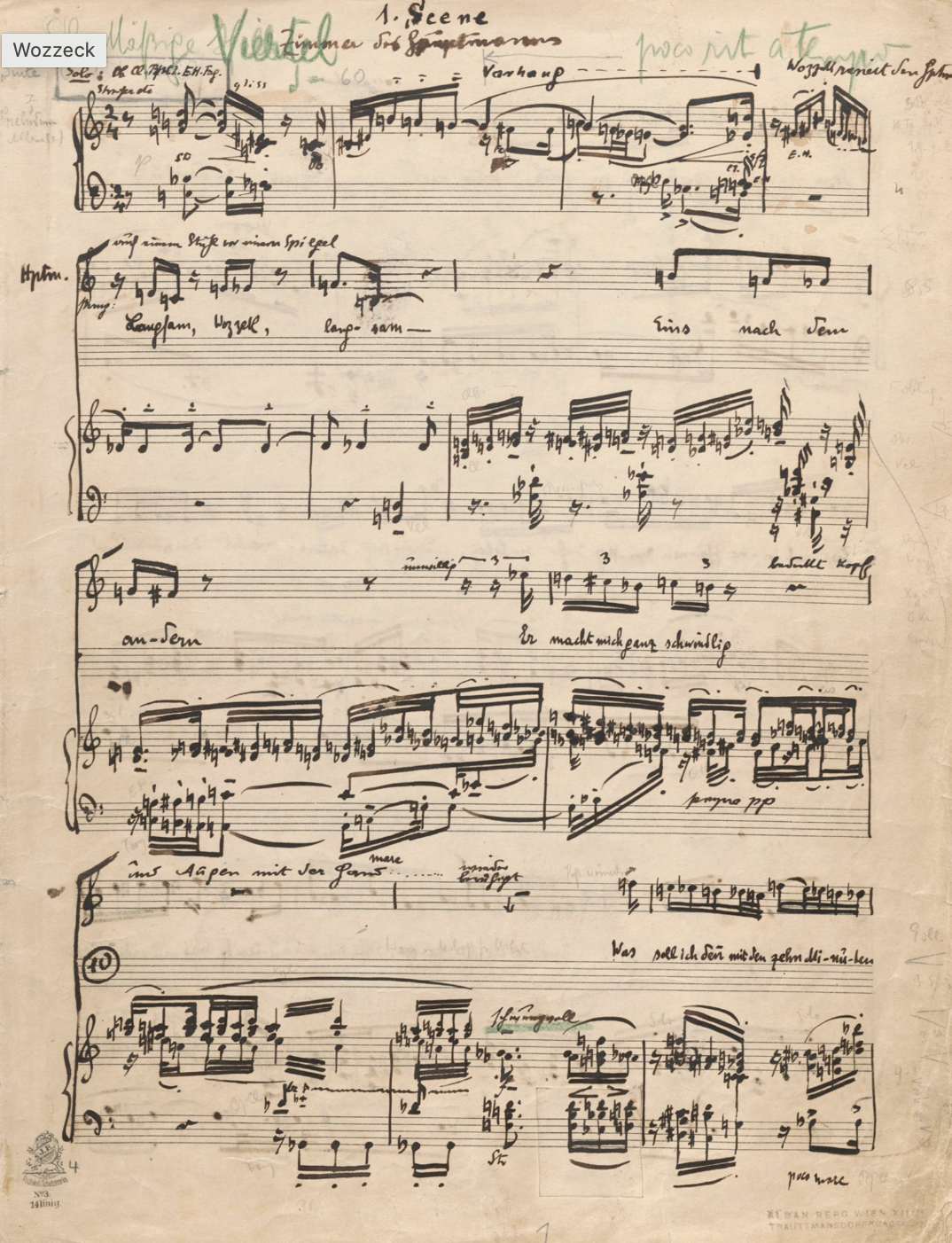

Fast forward to the year 1914, when the Bergs attended the first production of Georg Büchner’s play,Woyzeck, in Vienna. By the end of the evening, Alban knew he wanted to make an opera of it, and he worked to realize this desire for the next seven years, eventually settling on 15 scenes from the play that would be part of an opera with three acts (with five scenes each). He also adapted the libretto for Wozzeck, his first opera, which premiered in 1925.

Wozzeck (as sourced from the Alban Berg Villa)

A scene

In May 1925, Alban Berg began an affair with Hanna Fuchs-Robettin, the wife of a close friend. Elias Canetti knew her from shared social circles centered around the patronage of Hanna’s father, Rudolf Werfel, a wealthy manufacturer of gloves and leather goods.

How to set the scene for the tempests of 1925? Berg spent much of the year’s remainder navigating the popularity of his opera while composing Lyric Suite, which used a combination of his initials and those of Hanna (HF) as well as a melodic quote from Alexander von Zemlinsky's Lyric Symphony, which originally set the words “You are mine own.”

the catastrophe

Alban died on the night of December 23-24, 1935, at the age of 50. In the foreword to the letters of Alban that she edited, Helene wrote: “I lived for 28 years on earth in the paradise of his love — and if I had the strength to survive the catastrophe of his earthly death, it was through the union of our souls — an alliance long since forged — across time and space — in eternity.”

Elias Canetti’s memories of Alban Berg

As usual, looking at photographs of an absent person stimulates the writer to memorialize them. So Elias Canetti recollects his relationship to Berg in his memoirs, from which I quote extensively:

Today I have been looking with emotion at pictures of Alban Berg. I don't yet feel up to saying what my acquaintance with him meant to me. I shall try only to touch quite superficially on a few meetings with him.

I saw him last at the Café Museum a few weeks before his death. It was a short meeting, at night after a concert. I thanked him for a beautiful letter, he asked me if my book had been reviewed. I said it was still too soon; he disagreed and was full of concern. He didn't quite come out with it but hinted that I should be prepared for the worst. He, who was himself in danger, wanted to protect me. I sensed the affection he had had for me since our first meeting. “What can happen,” I asked, “now that I've got this letter from you?” He made a disparaging gesture, though I could see he was pleased. “You make it sound like a letter from Schönberg, it’s only from me.”

He wasn't lacking in self-esteem. He knew very well who he was. But there was one living man whom he never ceased to place high abort himself: Schönberg. I loved him for being capable of such veneration. But I had many other reasons for loving him.

I didn't know at the time that he had been suffering for months from furunculosis. I didn't know that he had only a few weeks to live. On Christmas Day, I suddenly heard from Anna that he had died the day I didn't know at the time that he had been suffering for months from furunculosis; I didn't know that he had only a few weeks to live. On Christmas Day, I suddenly heard from Anna that he had died the day before. On December a8 I went to his funeral in Hietzing cemetery. At the cemetery I saw no such movement as I had expected, no group of people going in a certain direction. I asked a small misshapen gravedigger where Alban Berg was being buried. "The Berg body is up there on the left," he croaked. Those words gave me a jolt, but I went in the direction indicated and found a group of perhaps thirty people. Among them were Ernst Krenek, Egon Wellesz and Willi Reich. All I remember of the speeches is that Willi Reich spoke of the deceased as his teacher, expressing himself in the manner of a devoted pupil. He said little, but there was humility in his feeling for his dead teacher, and his was the only address that did not grate on me at the time. To others who spoke more cleverly and coherently I did not listen; 1 didn't want to hear what they said, because I was in no condition to realize where we were.

saw him before me at a concert, reeling slightly when moved by some Debussy songs. He was a tall man and when he walked he leaned forward; when this reeling set in, he made me think of a tall blade of grass swaying in the wind. When he said "wonderful," half the word seemed to stay in his mouth, he seemed drunk. It was babbled praise, reeling wonderment.

When I first went to see him at his home—I had been recommended to him by H.—I was struck by his serenity. Famous in the outside world, in Vienna a leper—1 had expected grim defiance. I had thought of him far from his home in Hietzing and didn't stop to ask myself why he lived here. I didn't connect him with Vienna, except insofar as he, a great com-poser, was here to incur the contempt of the far-famed city of music. I thought this had to be so, that serious work could be done only in a hostile environment; I drew no distinction between composers and writers; it seemed to me that the resistance which made them was in both cases the same. This resistance, I thought, drew its strength from one and the same source, from Karl Kraus.

I knew how much Karl Kraus meant to Schönberg and his students. This may have been responsible at first for my own good opinion. But in Berg's case there was something more: that he had chosen Wozzeck as the subject of an opera. I came to Berg with the greatest expectations, I had imagined him quite different from what he was—does one ever form a correct picture of a great man? But he is the only one I expected so much of who did not disappoint me.

I couldn't get over his simplicity. He made no great pronouncements. He was curious because he knew nothing about me. He asked what I had done, if there was anything of mine he could read. I said there was no book; only the stage script of The Wedding. At that moment his heart went out to me. This I understood only later; what I sensed at the time was a sudden warmth, when he said: “Nobody dared. Would you let me read it in that form?” There was no particular emphasis on the question, but there was no room for doubt that he meant it, for he added encouragingly: “It was the same with me. Then there must be something in it.” He didn't demean himself with this association, but he gave me expectation, the best thing in the world. It wasn't H.'s organized expectation that left one cold or depressed, it wasn't the expectation that Scherchen quickly converted into power. It was something personal and simple; he obviously wanted nothing in return though he had made a request. I promised him the script and took his interest as seriously as it was meant.

I told him in what state of mind I had come across Wozzeck at the age of twenty-six and how I had kept reading and reading the fragment all through the night. It turned out that he had been twenty-nine when he attended the first night of Büchner's play in Vienna. He had seen it many times and decided at once to make it into an opera. I also told him how Wozzeck had led to The Wedding, though there was no direct connection between them, and I alone knew how one had brought me to the other.

In the further course of our conversation I made some impertinent remarks about Wagner, for which he gently but firmly reproved me. His love of Tristan seemed imperturbable. “You're not a musician,” he said, “or you wouldn't say such things.” I was ashamed of my impertinence, but I wasn't too unhappy about it. I felt rather like a schoolboy who had given a wrong answer. My gaffe didn't seem to diminish his interest in me. And indeed, to help me out of my embarrassment, he repeated his request for my play.

This was not the only occasion when he sensed what was going on inside me. Unlike many musicians, he was not deaf to words; on the contrary, he was almost as receptive to them as to music. He understood people as well as he did instruments. After this first meeting I realized that he was one of the handful of musicians whose perception of people is the same as writers. And having come to him as a total stranger, I also sensed his love of people, which was so strong that his only defense against it was his inclination to satire. His lips and eyes never lost their look of mockery, and he could easily have used his irony as a defense against his warmheartedness. He preferred to make use of the great satirists, to whom he remained devoted as long as he lived.

I would like to speak of every single meeting I had with him; they were rather frequent in the few years of our acquaintance. But his early death cast its shadow on them all; like Gustav Mahler, he was not yet fifty-one when he died. It discolored every conversation I had with him and I am afraid of letting the grief I still feel for him rub off on his serenity. I am reminded of a sentence in a letter to a student, which I learned about only later. “I have one or two months yet to live, but what then? —| can think or combine no more than this—and so I'm profoundly depressed.” This sentence did not refer to his illness but to the threat of imminent destitution.

At the same time he wrote me a wonderful letter about Auto-da-Fé, which he had read in that same mood. He was in severe pain and in fear of losing his life, but he did not thrust the book aside, he let it depress him, he was determined to do the author justice. He did just that and conse-quently this first letter I received about the novel has remained the most precious of all to me.

His wife, Helene, survived him by more than forty years. Some people ridicule her for “keeping contact” with him all this time. Even if she was deluding herself, even if he spoke inside her and not from outside, this remains a form of survival that fills me with awe and admiration. I saw her again thirty years later, after a lecture given by Adorno in Vienna. Small and shrunken, she came out of the hall, a very old woman, so absent that it cost me an effort to speak to her. She didn't recognize me, but when I told her my name, she said: “Ah, Herr C! That was a long time ago. Alban still speaks of you.”

I was embarrassed and so moved that I soon took my leave. I forwent calling on her. I'd have been glad to revisit the house in Hietzing, where she was still living, but I didn't wish to intrude on the intimacy of the conversations she was always carrying on. Everything that had ever happened between them was still in progress. Where his works were involved, she asked him for advice and he gave her the answer she expected. Does anyone suppose that others were better acquainted with his wishes? It takes a great deal of love to create a dead man who never dies, to listen to him and to speak to him, and find out his wishes, which he will always have because one has created him.

other materials

The library of Alban and Helene Berg in Vienna contains the composer’s original Bösendorfer grand piano, the desk from his study, more than 3,000 books or scores, and other small objects . . . . including collections, memorabilia, etc.

Berg collected coins, rock crystals, and mineral specimens. As a young man, he drew crystals in his notebooks. As an adult, he groomed a collection of American minerals. Among the coins displayed in the Berg library, there is a 10 centesimi piece from Italy dated 1862, a 10c from the French Republic circa 1915; 2 florins from the Kingdom of Belgium circa 1866, 2 Austrian groschen circa 1929, and a token for the screening of the Threepenny Opera film at the Sascha.

glücksbringer

It is unclear as to whether Alban Berg enjoyed his superstitions, but it is certain that he had them.

Among the lucky charms depicted below, there is a particular significance to the netsuke figure, since Alban made Helene promise to hold it secretly in her hand during all of his performances.

A 19th century ivory netsuke of Jurojin, one of the seven Japanese gods of good fortune, representing a long life.

Intertwined rings as a symbol of Alban’s indissoluble marriage to Helene.

“Eberzahn” charm that Alban liked to carry with him.

Horseshoe for good luck that Alban kept near at hand.

“andante amoroso”

Alban Berg gifted Hanna an annotated copy of the Lyric Suite score, who then bequeathed it to her daughter Dorothea. Held in the Austrian National Library, the score’s annotation reads in part:

It has also, my Hanna, allowed me other freedoms! For example, that of secretly inserting our initials, HF and AB, into the music, and relating every movement and every section of every movement to our numbers, 10 and 23. I have written these, and much that has other meanings, into the score for you. ... May it be a small monument to a great love.

As the Nazis implemented their genocidal campaign for national greatness fascism, Hanna Fuchs-Robettin and her husband, Herbert, fled Prague for New York City. He died in the US in 1949; Hanna survived him by nearly 15 years.

In 1976, fourteen of Alban Berg's letters to Hanna were discovered among her papers. Some had been carried between them by his admiring student, Theodor Adorno. Others had been carried to Hanna by Alma Mahler-Werfel, the widow of Gustav Mahler who had married Hanna’s father, and whose daughter — Anna Mahler — would leave a lasting imprint on Elias Canetti’s life.

Evidently, Helene Berg maintained an ongoing connection to her deceased husband. In her last will and testament, Berg’s widow forbade any perusal of the composition sketches for the opera Lulu or its performance in three acts.

“The more passionately thought denies it's conditionality for the sake of the unconditional, the more unconsciously, and so calamitously, it is delivered up to the world. Even its own impossibility it must at last comprehend for the sake of the possible.”

— Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia

“How do I (my eye) follow this sequence? I am present as if I were listening to music. How do these figures add up?”

— Paul Valery, notebook dated 1935

[postlude: Act 3 Wozzek]

*

Alban Berg, "Woyzeck, by Georg Büchner”

Alban and Helene Berg’s Library, as archived by Kulturpool

Alban Berg Villa

Dick Strawser, “Alban Berg's Lulu: Up Close & Maybe Too Personal (Part 3)”

Elias Canetti, The Memoirs of Elias Canetti

”Hanna Fuchs-Robettin” (Wikipedia)

Renée Fleming & Emerson String Quartet, Lyric Suite: A Musical Love Story

Thierry Raboud, “Alban Berg, notes secrètes” (La Liberte)