“How can you see your life unless you leave it? It is already late when you wake up inside a question. Pilgrims were people who got the right wish. I'm asking you to study the dark.”

— Anne Carson, The Anthropology of Water

Prior to leaving Europe I was engrossed in presenting psychological studies through the mediumship of forms which I created. Almost immediately upon coming to America it flashed on me that the genius of the modern world is machinery, and that through machinery art ought to find a most vivid expression...

— Francis Picabia, 1915

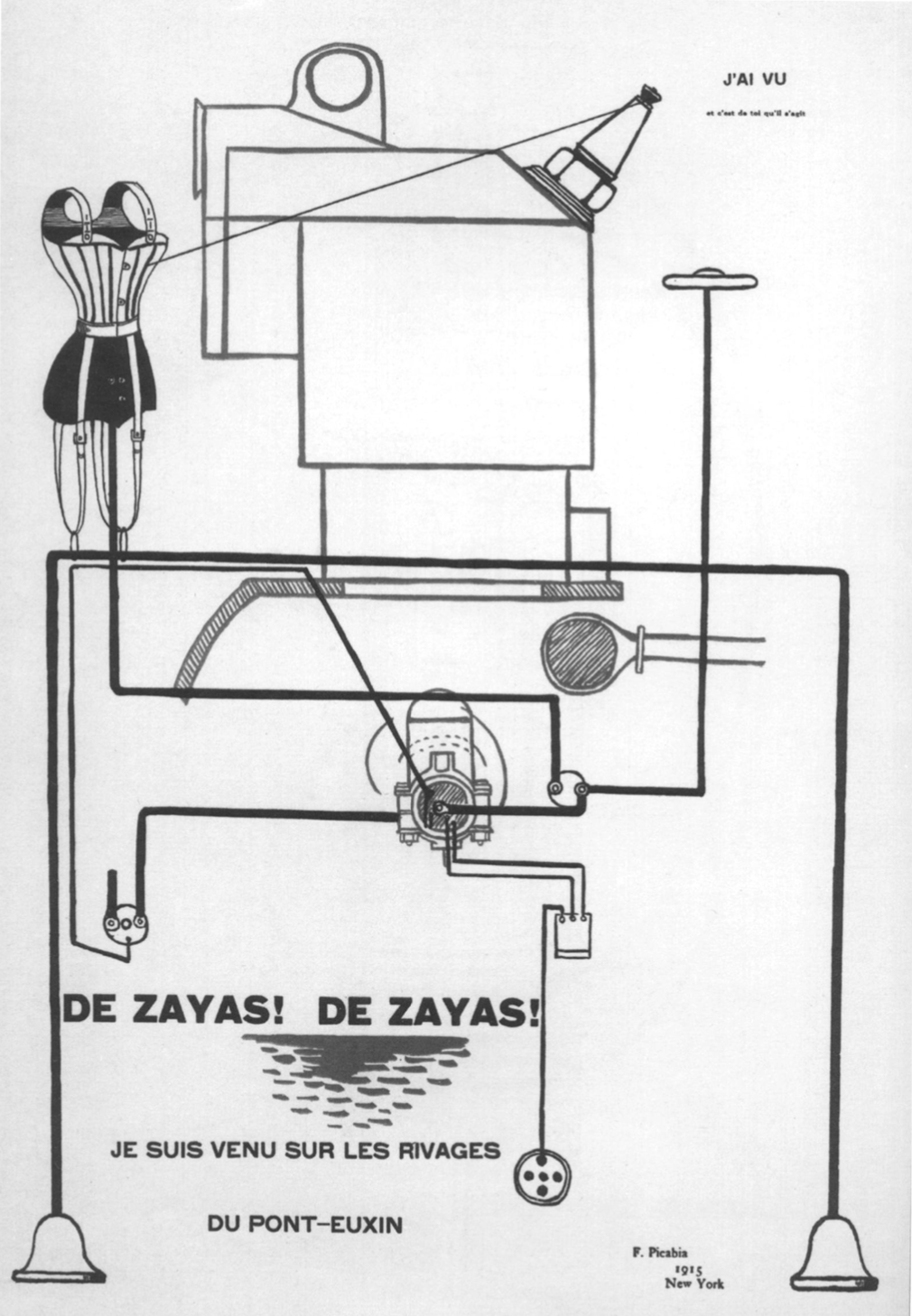

Francis Picabia’s machine portraits resemble closed systems: forms of being where possibility is automatically limited. Against the porosity of flesh and paper, these portraits give us indeterminate circuits that cannot be understood or penetrated.

De Zayas! De Zayas! (1915) is a caricature of the artist that announces its own emptiness. Picabia’s quotations and text juxtapose an allusion from Xenophon’s Anabasis (“Glimpsing the shores of the Black Sea after their long, arduous retreat from Persia, Xenophon's soldiers burst into cries of 'Thalassa! Thalassa!” ) with rendering of Pont-Euxin in French (“Je suis venu sur les rivages / du Pont-Euxin.” For the soldiers, the sea represents a highway that leads back to their homes.

Francis Picabia. Zayas! De Zayas!, 1915.

Ink on paper.

Following a tortuous journey through war-torn France and across the ocean, Picabia had finally found refuge in New York with his old friends. This greeting— 'De Zayas! De Zayas!,' — echoes the Greek outburst, exhibits the same joy. How to reconcile this quotation with the sewing machine and the machine portrait?

The exclamatory and exuberant expression . . . (I’m riffing here, or trying to find my thoughts) as if uttered by one who has arrived at a place, and needs to announce that arrival. The empty corset withholds the flesh, but it also withholds the representation of the flesh. Costumes only; no human subject with skin in the game.

Is the corset connected by a piece of thread to the bobbin in the upper right corner?

I see it as a bobbin; it evokes the interior of my sewing machine, just as the thread which descends from the corset’s crotch seems connected to interior gears and pulleys that also resemble a sewing machine. Surely that is button. Sewing makes and brings forth: it creates the subject that will be created by the costume, so there is double-creation here, or a duplicity that constitutes the modern subject.

“I have seen you in action and here you are”: this is how I would translate the tiny script located in the upper right corner. The striptease cannot satisfy the viewer?

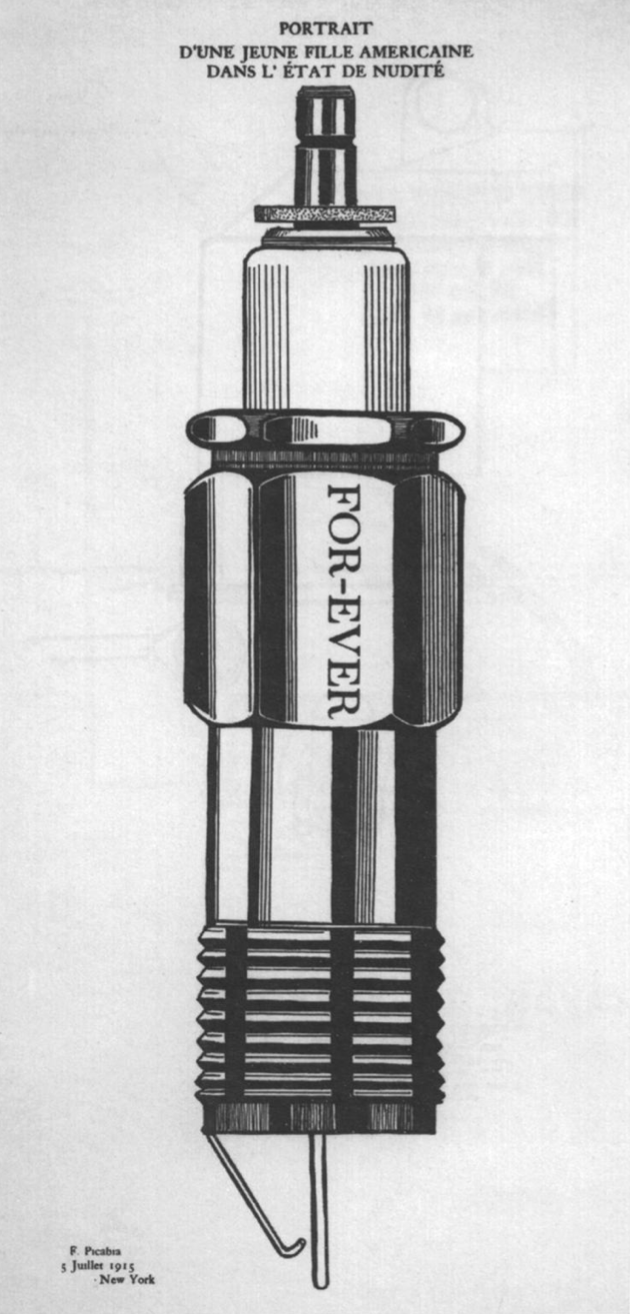

Francis Picabia, Portrait of a Young American Girl in the State of Nudity (1915)

Ink on paper.

When asked by The New York Times to comment on his work, Picabia replied:

I do not produce the original. You will find no trace of the original in my pictures. Take a picture I painted the other day, while here in New York. I saw what you call your ‘skyscrapers.’ Did I paint the Flatiron Building, the Woolworth Building, when I painted my impression of these ‘skyscrapers’ of your great city? No! I gave you the rush of upward movement, the feeling of those who attempted to build the Tower of Babel— man’s desire to reach the heavens, to achieve infinity.

*

Francis Picabia, Portrait of a Young American Girl in the State of Nudity (1915)

Francis Picabia, Zayas! De Zayas!, (1915)

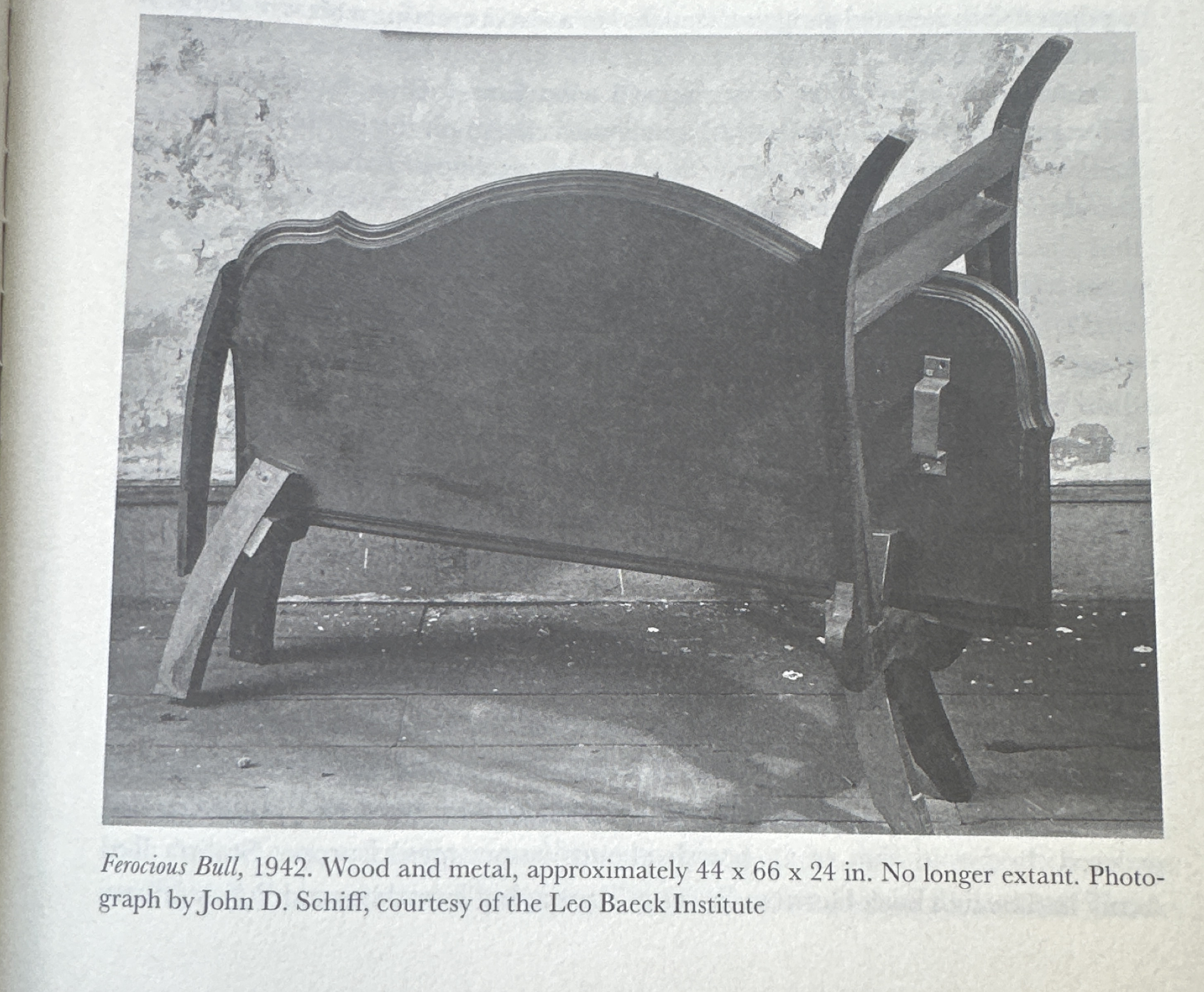

Louise Nevelson, Ferocious Bull (1942)

P. J. Harvey, “Guilty” (demo)