NATE: It's much easier to say we suffered eighty-nine casualties today than we had eighty-nine people were fucking ripped apart and killed today. Easier to say eight Gazans died yesterday of malnutrition or a so-called accidental so-called airstrike than to say four babies and their mothers were slaughtered in their beds by the Israeli war machine. This kind of debasement of language both covers over and leads to the debasement of humanity. It’s disturbing. On a much different note but in the same ballpark when it comes to the use of language, it’s easier for a university president to use the term AI use than it is to talk about how plagiarism is running rampant on college campuses. A creative can benefit from AI use—potentially—but an artist can’t. If they have any self-respect, they know it.

ALINA: In my late teens, I visited the Vietnam Memorial to DC. A few men were sitting in lawn chairs next to a sign: Vietnam Vets Against the War. The vets led me to Howard Zinn. Those names on the wall trembled, shifted, became lacunae about empire. Each name had a person buried inside it. Nobody spoke of them as people who had put themselves in a position where the only thing they could do without being declared a traitor or an enemy of a nation was to keep going forward. Among the stone monuments, I felt the power of systems, and heroism, exemplarity, resume-building . . . What we construct as “success’ became horrifying. To love the world, I had to become a pesso-optimist.

NATE: What you're saying about these names and the power of names and naming reminds me of something I write about in my novel. One of the scenes in Daybook is about going with my kid to the Confederate cemetery at the battlefield in Franklin for the Confederate dead. Instead of proper headstones with names and dates—in part because such a spectacular amount of Confederate soldiers were killed in that battle in the space of little over an hour, well over a thousand men just absolutely mowed down like grass facing a lawnmower blade, this necessitated first burying them where they fell and then reburying them later a few hundred yards away—this particular cemetery just has blocks in the ground with initials on them, grouped around the various states that the soldiers were from. There are no names, and the starkness of that is striking when you walk through that cemetery. I don’t write about this particular aspect in the book, but I later learned that one of the soldiers buried there was a Chinese immigrant who fought for the south. Not the kind of Confederate soldier that first comes to mind. But he was a person, a person caught up in an enormous and doomed fight that is usually framed in the popular imagination as being a pitched conflict between two very clear ideological perspectives, one based on enslaving black people and one based on the idea that all people should be free. While there is definitely some truth in that way of looking at the war as a war, to do so ignores the fact that individuals took all the risks for one reason or another. A Chinese immigrant would seem to make a very unlikely Confederate soldier—but for one reason or another, he was one.

ALINA: You know, we have a powerful need the belong. When I was young, my parents would put up the flag a day earlier and take it down a day later than everyone in the neighborhood for the Fourth of July.

NATE: Why?

ALINA: Because they were defectors and they needed to prove that they were American enough. And when you mentioned these immigrant names,I think about the longing to be “of”, the hunger for belonging. We seek validation through this idea that we can belong to a group. And when we talk about nationalism or Trumpism or ethnostate ideologies– we open the darkest box of the human heart. How do we as writers—your book is so much about the loneliness of the writer—well, what's up with us?

NATE: I’d much rather you answer.

ALINA: I’ll pass on this dildo, to paraphrase William Gass.

NATE: I don't know about this dildo. Can you rephrase the question? What's up with us in which sense?

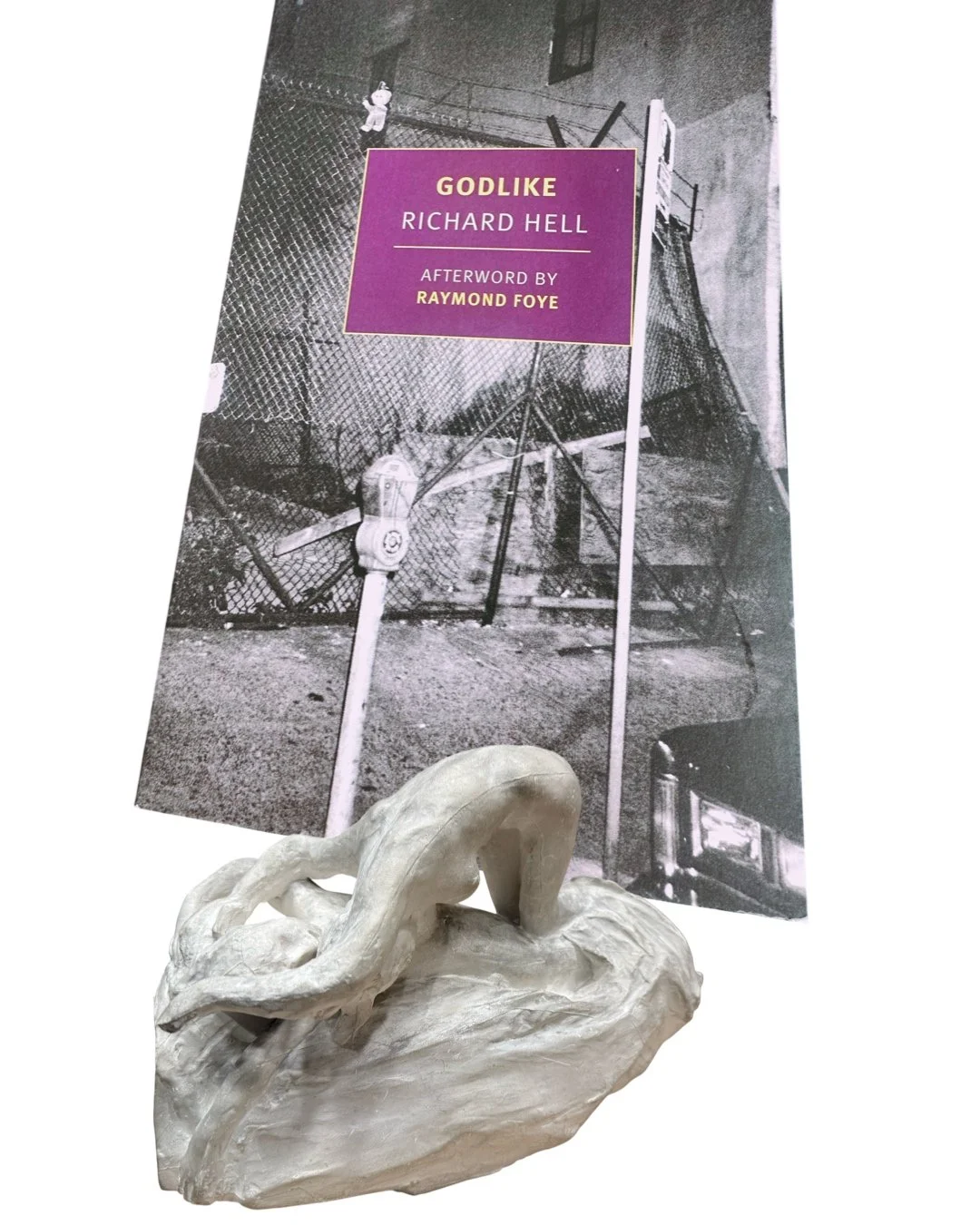

ALINA: How do we resist the urge to belong? Like, what is it about in your book when I read…when I read the desire, your book? And this is related to the difference between minor literature versus the mainstream, because I think bestsellers want to belong and do belong and create the conditions for belonging and mimic the terms of belonging—

NATE: Sure, but about the dildo—

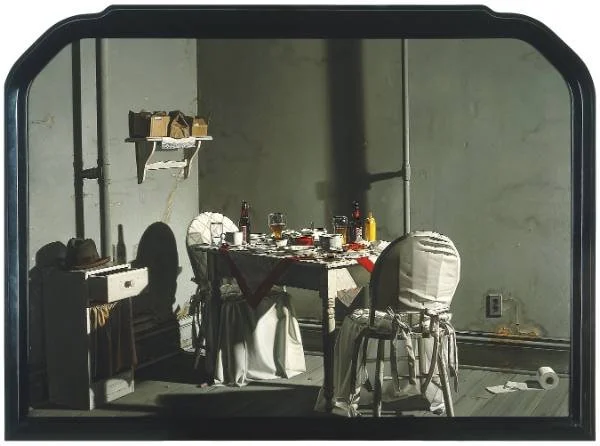

ALINA: —whether religion or sports team or fan culture or whatever sense. Your book doesn't give us a solution for belonging, doesn't ever belong, the speaker doesn't ever belong, and I'm interested in what it is that enables or creates the capacity in a human being to give up on that.

NATE: I don't know. I don't really feel like I ever have belonged. Not that I think I’m special in that sense. Almost everybody feels this lack on some some level—and I’m curious, too, about some of the ways in which you talk about this in My Heresies, like the poem where you talk about the rapture/Left Behind craze and how someone tells one of your kids the antichrist will be Romanian.

ALINA: Ha ha. Poetry is a constellating medium of thought for me. I was thinking about how Tim LaHaye and Jerry whatever, the authors of the Left Behind series, really testified to literature’s capacity to shape social change and ‘revelate’ new interpretations of scriptures in the novel. Left Behinders believe they are “chosen” – and this idea of chosenness is the source of every originary ethno-supremacist myth in the Balkans – so you have one group that has been chosen to occupy a particular geographic land by some transcendent being. . . and who can argue with a god? No evidence or reality can challenge that fiction. Social conditions aren’t simply reflected in culture representations. Social conditions are also developed and normalized by those fictive representations. The dynamic between facts and representations isn’t cold or set: it’s hot. It keeps moving. So, how do specific social representations become influential and internalized? Publishers, academics, patrons, and institutions pad the influence pathways. The media monetizes the performatives and passes the new myth along. The story is absorbed until that description becomes a usable fiction, one that finds recognition more broadly and becomes heritable. The birth of the national “self-image” competes with the religious icon in art. Look, your antichrist is the story you tell about the story that makes you feel “safe.” But feeling ‘safe’ isn’t compatible with thinking. Since Dante, the poet has been tasked with describing the inferno. I pledged myself to describe the corridors of the present through the eschatological hunger that constructs hell?

NATE: Are “the corridors of the present” where the dildo went?

ALINA: What dildo?

NATE: The one that you said belonged to William Gass.

ALINA: No, it is in New York now—paving the way for vital new work in the so-called corridors of the present.

NATE: That is a tough one. Let us hope so.

ALINA: Yes. But you were talking about resisting the urge to belong.

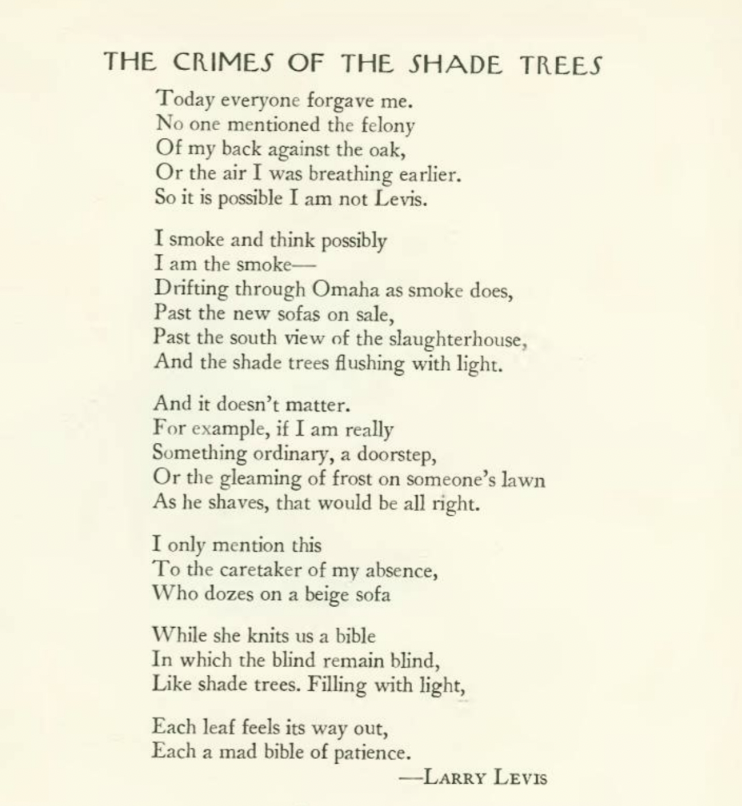

NATE: Right. I’ve never been interested in it. The people that raised me weren't joiners and I’ve never been one either. Most of the people involved in any particular group or pursuit or scene are either profoundly mediocre in any case. As the old cliché goes, I wouldn't want to belong to any club that would have me, and I've always lived for the most part outside of the so-called literary community. For a long time I felt really angry about the fact that I couldn't sell my books even after I got an agent. It felt like New York wouldn't have me.

ALINA: But was that anger good for you? As a writer?

NATE: Yeah it was, it was because it was like, okay, I'm going to do my own thing.

ALINA: You gave up, you stopped trying—

NATE: Exactly. Stopped caring about it, stopped trying. But even in towns where I've lived—not the Capital L Literary Community, but the smaller ones, I've never really wanted to be a part of them either. No interest in being part of a group. And I think that goes back to the fact that I was raised in this very, very insular version of Christianity, where I was part of the group, and even that never felt good.

ALINA: Do you think it's because you were aware of the conditions of being part of that group?

NATE: Yeah, that they’re de-humanizing. The conditions to be a part of a group are always dehumanizing.

ALINA: [nods]

NATE: Which is the thing that brings me back to Gombrowicz over and over again because that's what he talks about. To be with other people in a group setting–to fit in–is to give up who you are. To deny who you are. Can’t avoid the suspicion, which definitely comes from my childhood in evangelicalism, that to truly become a functioning part of a scene or something would mean to cease to be myself.

ALINA: This makes me think of my favorite book by Thomas Bernhard, My Prizes.

NATE: I adore that book.

ALINA: The reason I love My Prizes even more than I love his memoir, which I love so much—

NATE: Gathering Evidence is my favorite of his!

ALINA: When I read the memoirs about how much he loved his anarchist grandfather, I understood Bernhard completely, in some way. That said, My Prizes does an incredible job of pointing out exactly what it is in literary "community” that asks us to accede, to give up, to in a way to, um, to perjure ourselves, right? I think we forge—

NATE: Perjure?

ALINA: Yes.

NATE: That’s an interesting word—

ALINA: I think we forge…hold on, let’s go back to your last name. Knapp. What did you say [before the play began] that it means in English? I think you said it refers to a blacksmith?

NATE: Sort of—it means to work with stone.

ALINA: So to work with stone, to forge something, but to forge something also means to fake something.

NATE: Well, in the original old English sense the sense is not to forge, but to make a tool.

ALINA: To make a tool, right. My dad is a metallurgist, and he talked about forging steel a lot. I used to wonder if he knew it also meant forgery, or faking it? For me, as a child there was this physical love of language that gave me goosebumps when my dad said, “I forged this steel.” As a writer, were there moments in your young days when you recognized that your relationship to language was different from other people’s?

NATE: Not my relationship to language, that came later. But my relationship to stories and the fun that could be had with them—that was very early on. That and the deliciousness of being in another person’s world, inside another person’s head, another person’s life. But my relationship to language in terms of being conscious of language itself came a lot later. But I say that in terms of a writer’s conscious relationship to language. My people on the mom's side where I grew up, in far southeastern Oklahoma, have one of the most particular ways of using the language that I know of, they speak in a dialect and accent that exists outside of the norm even for southern-leaning English speakers. When I first brought my to-be wife, who’s from the pacific northwest, to meet my grandfather, she could barely understand him.

ALINA: Wow.

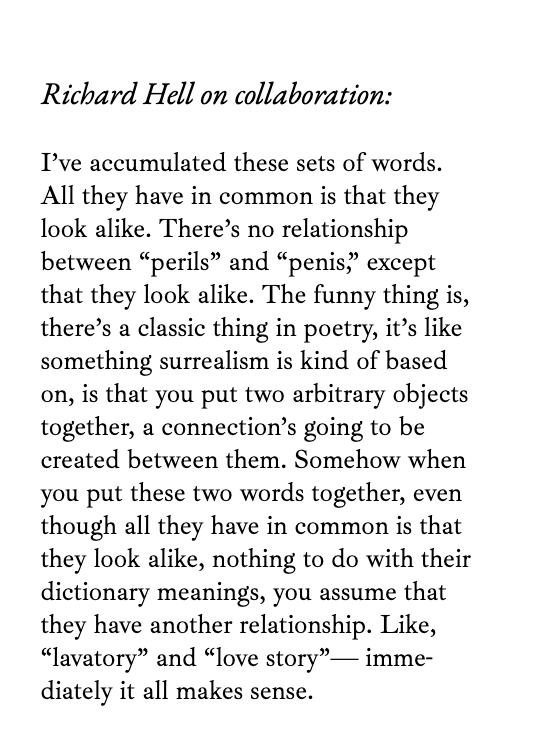

NATE: It's very particular. Or maybe I mean peculiar. It’s a variety of southern accent, I can imitate it later [thankfully, he did not –ed.], but I was aware early on of there being something interesting in the relationships that obtain in the sounds of words, because my dad, who came from a different part of the state, didn't speak with an accent and I don't speak with an accent—or at least for the most part no longer do. In any case, paying attention to language as a writer came a lot later. Long after my interest in storytelling, which is a bit odd to me now because I don’t particularly care about storytelling anymore except in the sense that one’s use of language in telling the story influences that story and vice versa. The one influences the other but language tends to arrive first.

ALINA: The wind is blowing in your hair. There’s no way the interview can convey the way the wind is blowing your hair right now.

NATE: If you want it to be in the interview, you’re going to have to put it in [laughs]. Like at the beginning of the piece you could say something about the wind blowing—

ALINA: Like it was like a Bon Jovi video, but not—

NATE: I think if you describe it that way in the published interview I would come back down here to Birmingham and kill myself. In your house.

ALINA: [Laughs.]