… but I wonder if this constant announcement of pain, putting one's subjection to work isn't a sort of gimmick, a trafficking in a type of disaster capitalism.

— Roger Reeves

under the bridges what springs up rises

out of a name more tragic than the absence

of lovers above

— Jean D’Amérique, “under the bridges what springs (up)

This is to confess my untold delight in the postal service’s delivery of a book titled workshop of silence, containing poems by Jean D’Amérique, as translated by Conor Bracken.

In his translator’s introduction, Bracken notes that Jean D’Amérique’s lived experience is unsettled by the boundaries of nation-states: “As a transnational person who splits his time between Haiti, France, and Belgium, not to mention a Black transnational person transiting through and living in historically white countries, he is subject to the rough, reductive, and at times lethally armed gaze of bureaucracy.” Borders, as written by this poet, “are not meant to be stopped at”; their existence is arbitrary and alienating.

Since D’Amerique began as a slam poet, Bracken says that “retaining this transgressive, playful, and dexterous attention to sound” was one of the primary goals of his translation— a goal that frequently leads him to slight departures from the denotative meaning of the original words. Translation is an art. As such, translators make choices about what to emphasize and convey across languages. Bracken elects the “enlivening of language” that restores “its fundamental slipperiness,” or, in his own words:

It is based as much in play and wit as it is in the political dimensions of the work that he's doing with these poems, which sometimes announces itself without embroidery, as in “moment of silence,” wherein he situates his poems in the political tradition of Nazim Hikmet, and at other times is more recondite, as in “under the bridges what springs (up),” where he points out through elaborate wordplay the continued but unexamined presence of the lexicon of shipping and chattel slavery in economic chatter.

I hear this subversive jouissance trickling upwards through the sap of “solar brass,” a poem that tingled all the way to the tips of my fingertips when I first read it.

solar brass

my rhapsody

a cactus in the night-call’s port

for sale for tropical cents

I am a solar

powered brassy jacket

the horizon

looks punk to me

D’Amérique’s poems have a purpose in daily life: they process the banalities and polish the repetitions.

A day spills between the materials of living as found in the grocery store. . .

poem for running errands

to be recited aloud while

going up and down the aisles

coffee filters

daybreak mouth agape

onions shallots

fresh bread hitched to mornings

omelet of youthfully innocent sun

beans verging on green

dusk

a little olive oil

for sopping up memory grated cheese

poem running against amnesia

don’t stop

until you bail the basket out

and pay the register with tenderness

As if to welcome the small details of the day in each purchase by turning the grocery list into a way of loving the world.

The quantum of D’Amérique’s “building the burden” strikes me as the teens unpack boxes filled with decorations.

building the burden

flesh dressed in awareness when the blade appears

fills the absence we defies

here where the hour

finds the guts to weep for its childhood

the ditch brimes with future

interrogating a life

whose reply is a stele

here is a curtain

an ulcer on the sight

lacking passerby the window’s unfinished

forever metal the mouth exalts the eclipse

parallel sentences brooding over what’s withheld

if you want a burden

take this poem run aground by boundaries

The possibilities inherent in D’Amerique’s poems remind me of the energy inherent to the act of “calling a thing,” which is to both name the thing and to summon it into being while imagining one’s self in relation to it.

[Yes, what is a self? the poet wonders.]

Certainly, a self is something kinned to the selfing described by Roger Reeves in his essay, “Poetry Isn’t Revolution But a Way of Knowing Why It Must Come”:

A self that might like to lie down in a field in the rain and take a nap. A self that might want to cuss and cut up on a Saturday night and go to church on Sunday morning and be holy all in it. A self touching and seeing a self in a way that a self wants to be seen, touched —without the veil. In lowering the veil for our children and for ourselves, we allow them, we allow ourselves, to see, to know, to diagnose power and its abuse. We give ourselves a world, a sound for the sense and tense of our lives.

Building his essay through repetition of a line from Solmaz Sharif’s poem, “Look,” Reeves repeats: “It matters what you call a thing.” And again:

“It matters what you call a thing.” When calling a child child in a Black household, it means so many things. It is calling them love, young, be here with me. It is calling forth a hedge of protection around them not as a way of absconding from danger but because of the awareness of it, because there is no out from danger. In this way, a Black parent is a poet; they call a thing into being. Child. But they have also called their child into language. In this way, a parent is always their child's first poet; an announcement of liberation- “not less of love but expanding / Of love,” to borrow from T. S. Eliot's “Little Gidding.” The parent becomes the child's first instantiation of ecstasy, of know— knowing how to use language, to author, an invisible future into being.

In the year of my unmooring, I could not have imagined that Roger Reeves’ Dark Days would mean everything to me— and this is precisely the joy of it. The reminder that I can be astonished; the muddle in my head turned to mush; the smallest syllables reconnecting into utterances.

And so, what follows is a length excerpt from an essay by Reeves aptly titled, “Reading Fire, Reading the Stars” — because we are still reading the worlds that need imagining in order to inhabit a future. . .

As Frederick Douglass noted in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, reading promotes an imagining, a worldmaking that can directly and emphatically contradict one's present circumstance, contradict the language weaponized against oneself-slave, three-fifths, chattel, property. When reading, one does not passively receive the words of others, one makes — makes a sentence, makes a paragraph, makes a book, makes a world, makes an argument. One authors. And sometimes in the reading, in the authoring, one creates a counter-narrative and counterargument particularly when reading something like Thomas lefferson's assessment of the poetry of Phillis Wheatley or reading the pathologizing of Black families in the Moynihan Report.

In other words, one makes a possibility, a possibility that hitherto did not exist. In reading (which is also an act of interpretation), one finds language for what is possible, what is untenable about the present, what must persist beyond the present. Reading, therefore, is always an act of making a future, an act of speculation. Even if one is only speculating about what one wants at the grocery store later. I should explain. In graduate school, I took a course on performative rhetorics with a brilliant rhetorician and philosopher named Diane Davis. In the class, we were discussing the prognosticative nature of language, how we never write for who we are but for who we will be; that language is always imagining us in the future. And she gave the great example of the grocery list. We sit down and write a grocery list in order to remind our future self of what the past self wanted. The list anticipates our forgetfulness, our future self being somewhere else, in some other headspace, after waiting for the bus, for example, or working all day. In this way, writing anticipates need, what the future self needs even if, for a moment, unaware.

This is why reading is dangerous— because it points.

Reading points to the necessity of pleasure, of longing, of desire—- even if in the words of others, even if desire is nowhere in the text that one is reading.

Reading itself is desire, desirous, a playing in and with the illicit because reading allows one to occupy a dream, the not-yet inhabited. Reading points to the invisible, to what must be created that doesn't exist.

Reading can also point to what exists but is not always acknowledged—one's freedom, for example.

Again, think of Frederick Douglass—his coming into literacy as an enslaved boy. In the act of resisting his master's desire for him not to learn to read, in disobeying the slave codes that made it illegal for enslaved people to learn how to read, Douglass began to cultivate not just literacy but the stuff of his abolition, his self-making. Reading became the introduction and practice for his personal revolution. Reading helped to prepare Douglass and his imagination for the question, What might my freedom look like? And, the practice of reading helped him answer it. Reading points to that which is against genocide. Or at least the reading I'm interested in doing, the reading that begins on the edges of plantations, in small groups of study, away from the eyes, appetites, laws, and codes of the masters and their policing patrollers; reading that announces the future, reading that disobeys, critiques the present through pointing, pointing away to the swamps and marshes where we might convene something like freedom.

Maybe we begin here— at the end, at what feels like the end of a certain type of America, the end of a certain type of democracy, a certain type of truth or at least an allegiance to it. Maybe this troubling of truth has been the question of art, art in America, all along— how do we begin democracy, how do we extend democracy to all the animals?

And if you can bear one more subjunctive statement, maybe a poem will show us how to begin or extend democracy to all the animals.

(Note: some italics in the excerpt are mine, as is the dissolution of Reeves’ paragraph including the sentences that begin with “Reading” into separate lines or celestial trajectories.)

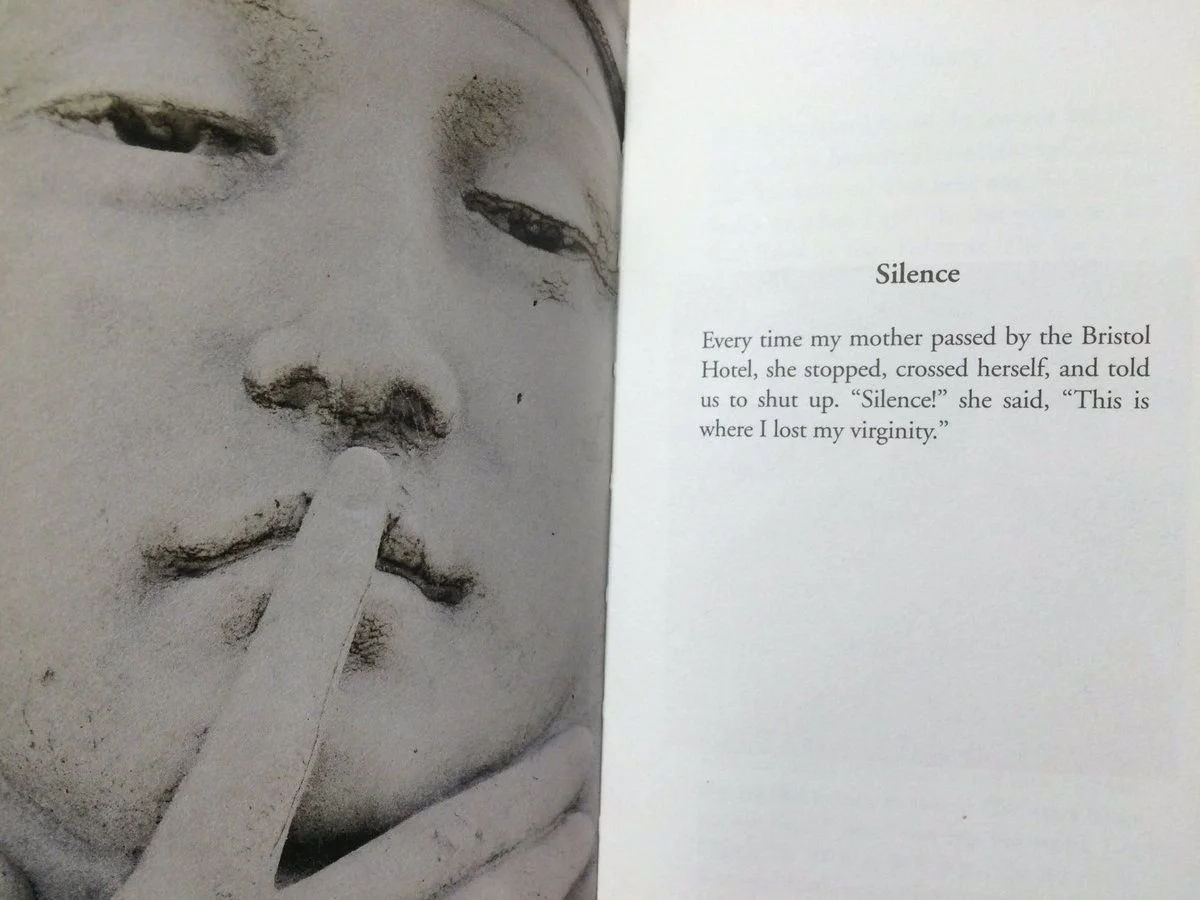

Sophie Calle.

“Hiding places there are innumerable, escape is only one, but possibilities of escape, again, are as many as hiding places. There is a goal, but no way; what we call a way is hesitation.”

— Franz Kafka, The Blue Octavo Notebooks

*

Decostruttori Postmodernisti, “Gnossienne n°1” by Erik Satie

Decostruttori Postmodernisti, “If the Theremin was Pavarotti”

Eleni Karaindrou, “Ulysses' Gaze”

Jean D’Amérique, workshop of silence, translated by Conor Bracken (Vanderbilt University Press)

Roger Reeves, “Poetry Isn’t Revolution But a Way of Knowing Why It Must Come” (from Dark Days: Fugitive Essays)

Roger Reeves, “Reading Fire, Reading the Stars” (from Dark Days: Fugitive Essays)

Sophie Calle, “Silence”