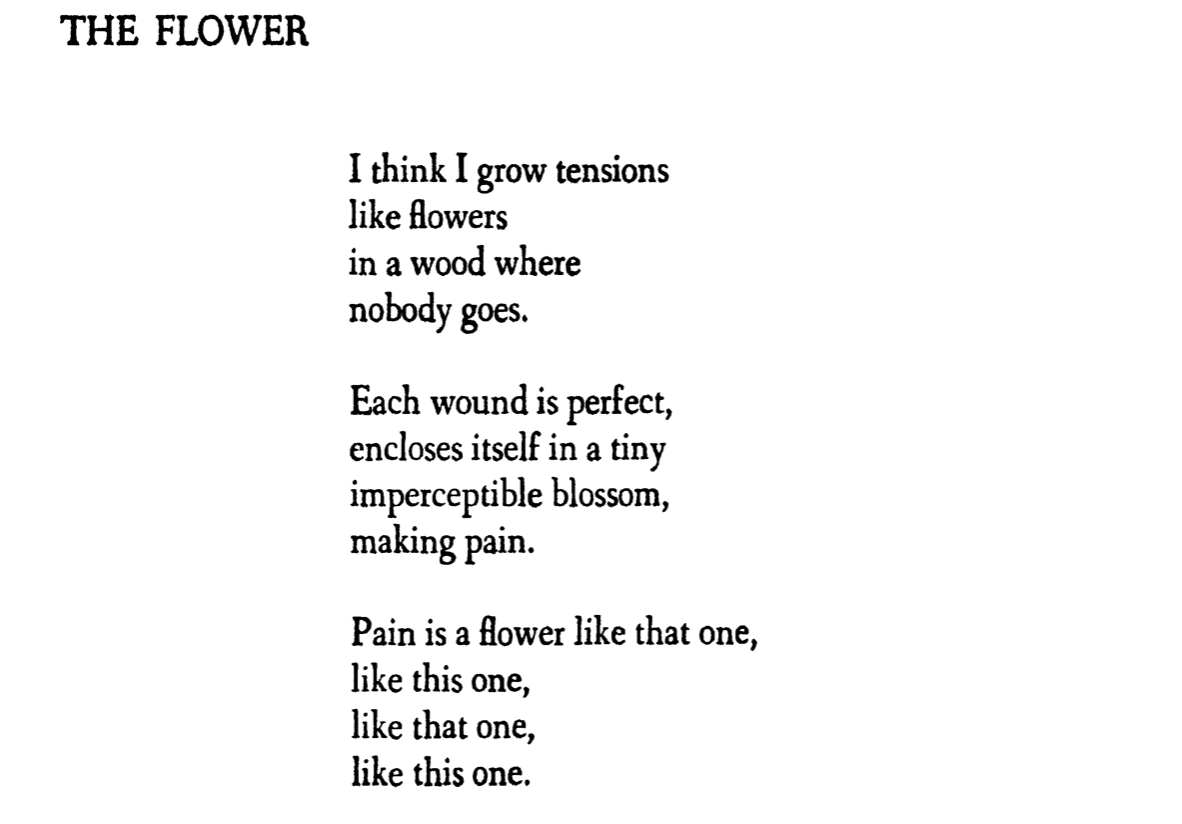

We measure depth

as a fathom of waters

as a keeper of otters

as a fear of disorder

as a phantom of operasAn exclamation point in the shape of a question mark

against the earth and your flesh

against the canopy

[Rene Char, “Continuous Truth” tr. by Nancy Carlson; Hannah Aizenmann, “As a Father of Daughters”; ibid.; ibid.; ibid.; Alberto Rios, “Seahorse in the Desert”; Christopher DeWeese, “If You Hide Long Enough, Sometimes You'll Forget You're Riding”; Rajiv Mohabir, “Leela”]

The Gust of Ghost-forsaken Places

Last week, I returned to my notes on Samuel Beckett, and thought about his relationship to the memorial, and to memorialization. Despite having lived through two extraordinary wars, Beckett rarely addressed the memorial form directly in his work. But there a poem — and a radio play — and a place.

Saint-Lô

Vire will wind in other shadows

unborn through the bright ways tremble

and the old mind ghost-forsaken

sink into its havocSamuel Beckett

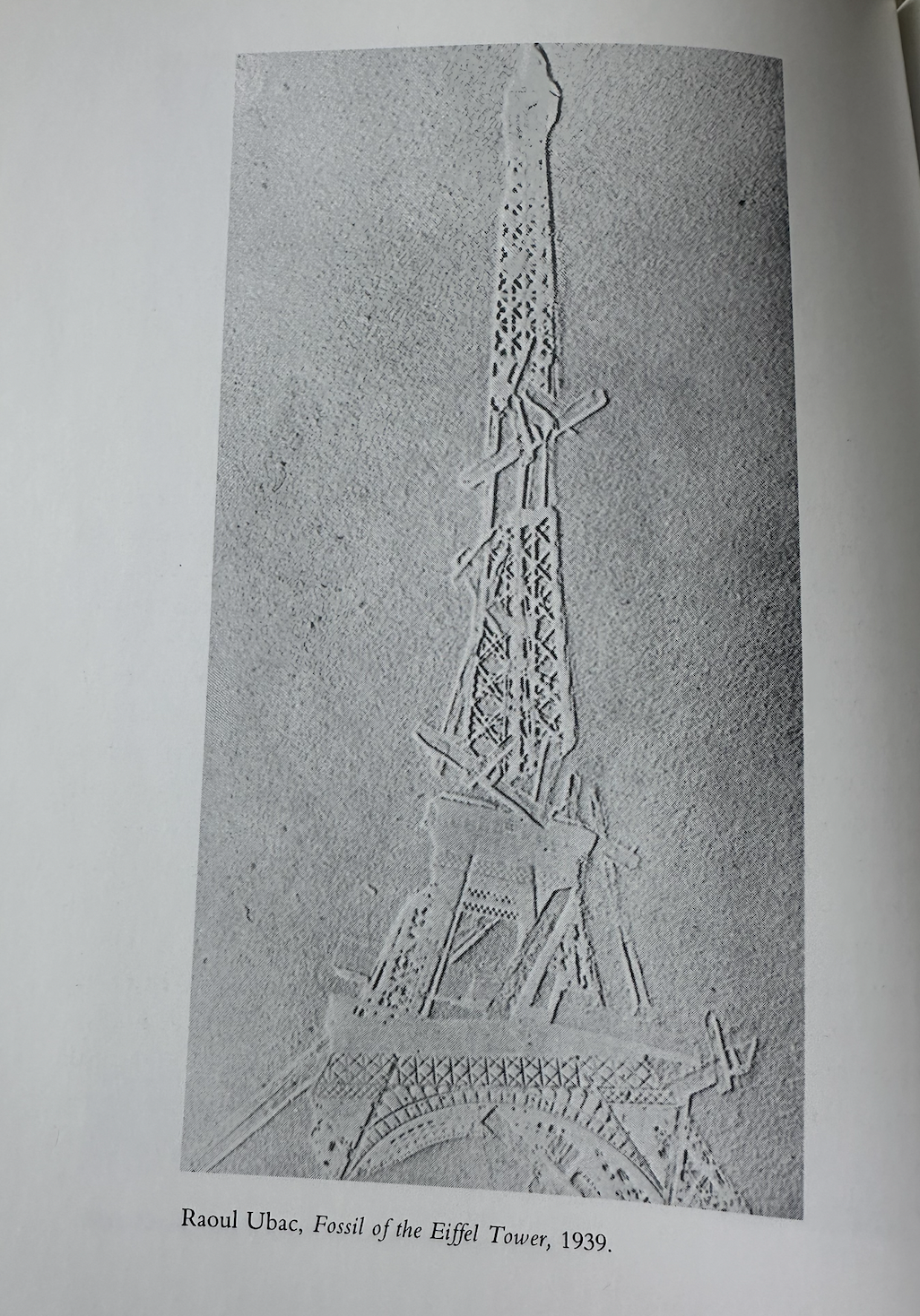

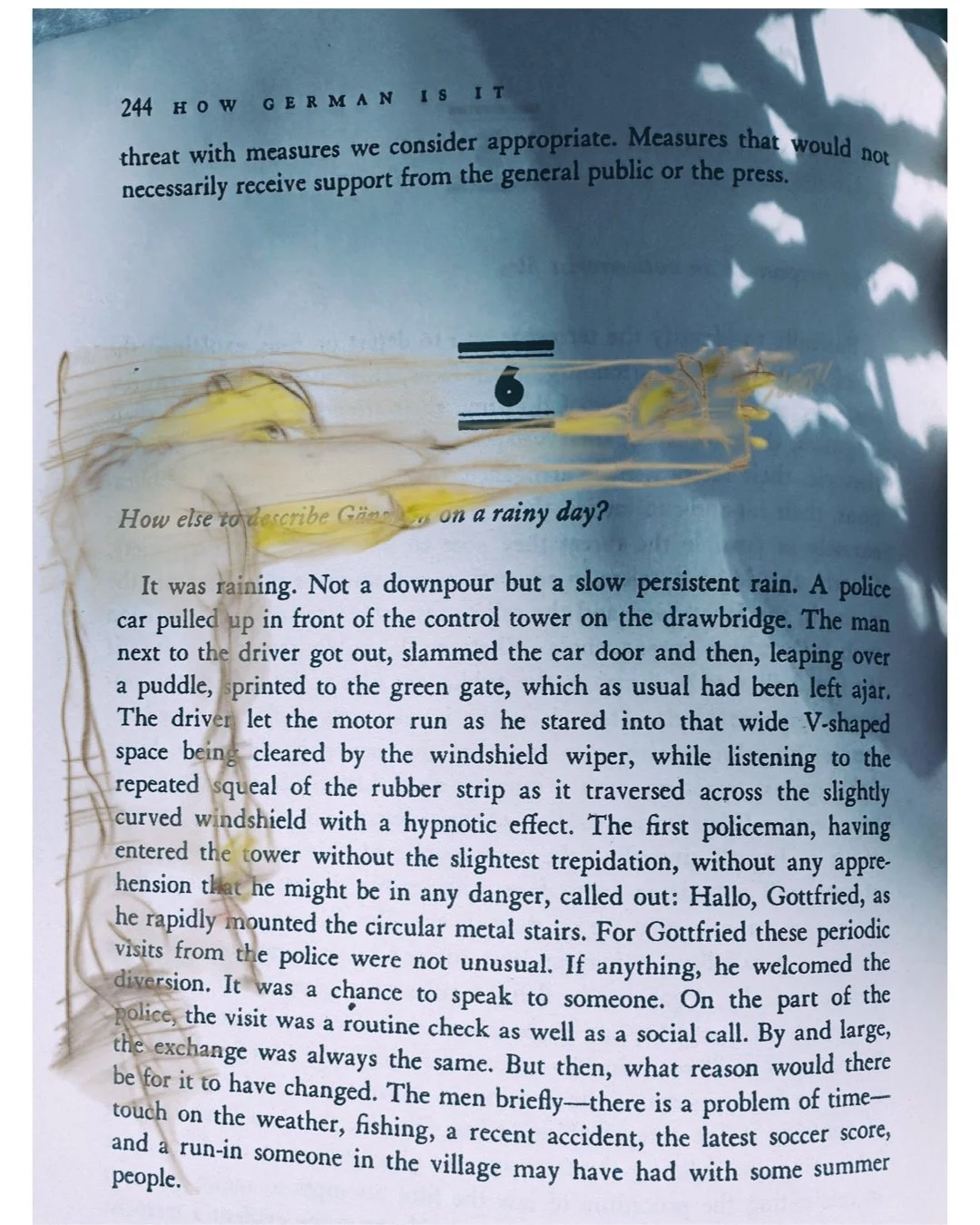

“Ghost-forsaken” clings to “sink”: Beckett committed the site of Saint-Lô to the poem’s memory. But he also returned to it quietly in 1946, withThe Capital of the Ruins, an unproduced radio play he created for Radio Erin. And we don’t know where he stood or what he kissed when giving the following words to a play that got buried: “Saint-Lô was bombed out of existence in one night. German prisoners of war and casual laborers attracted by the relative food-plenty, but soon discouraged by housing conditions, continue, two years after the liberation, to clear away the debris, literally by hand.”

The Gust of Wind

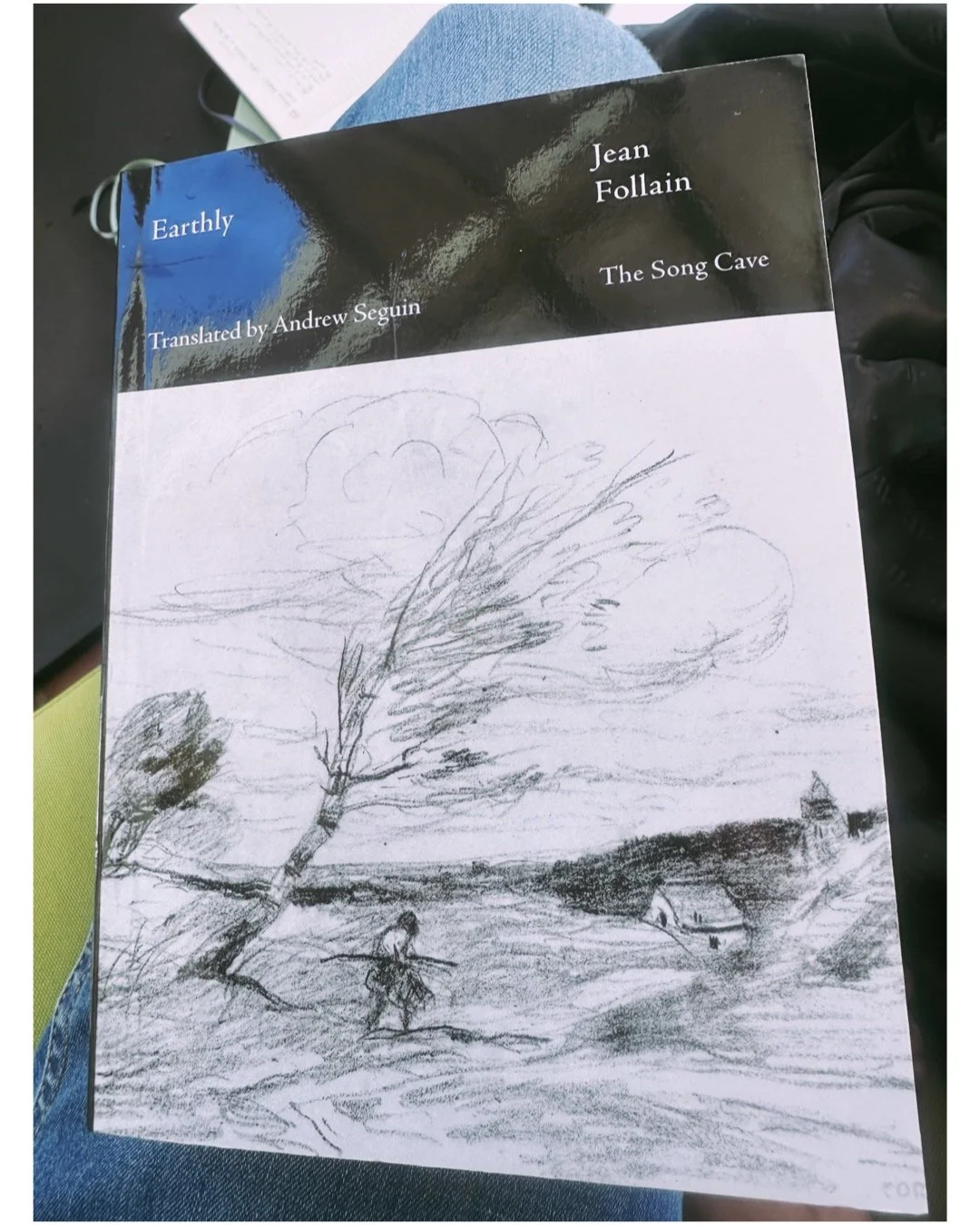

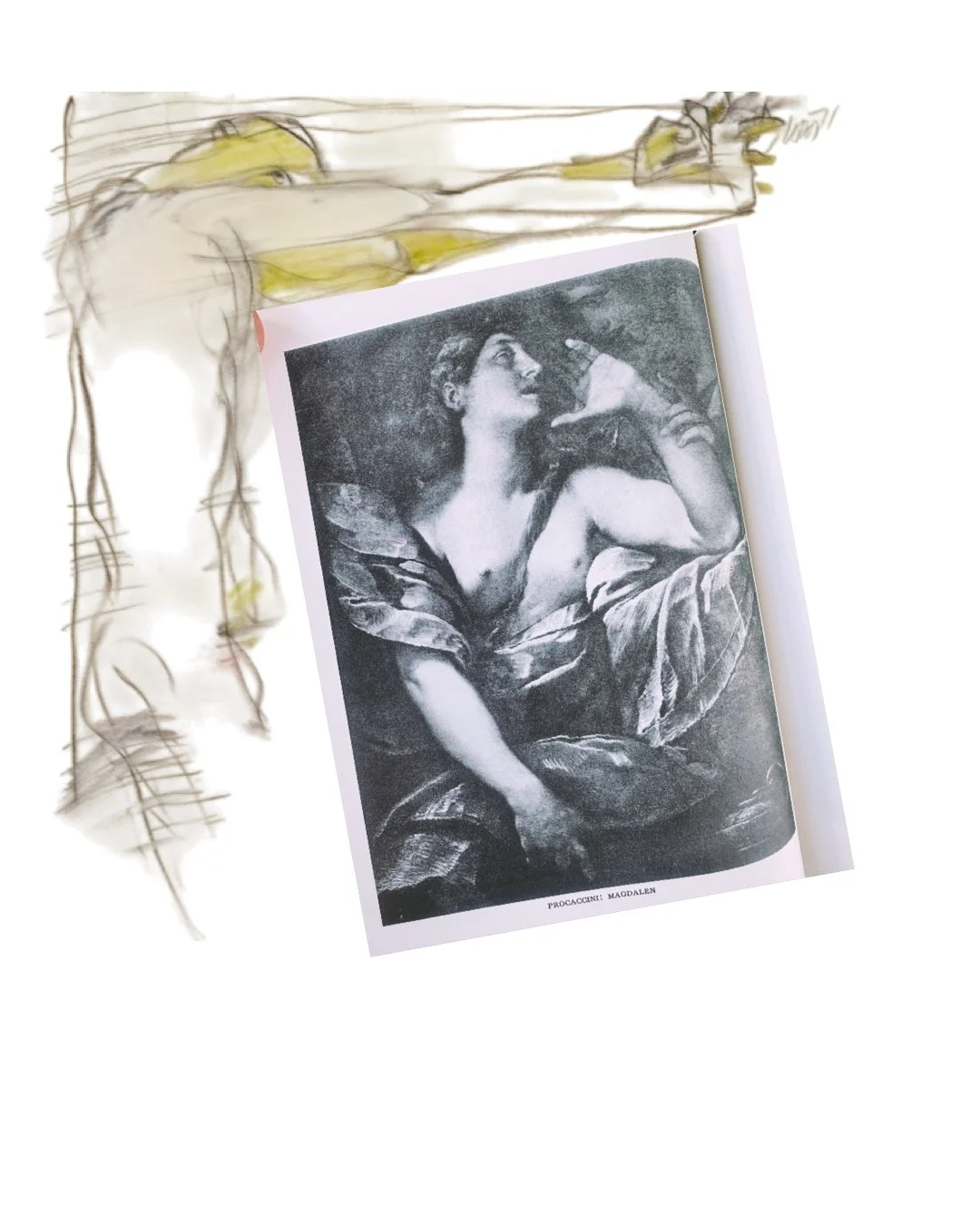

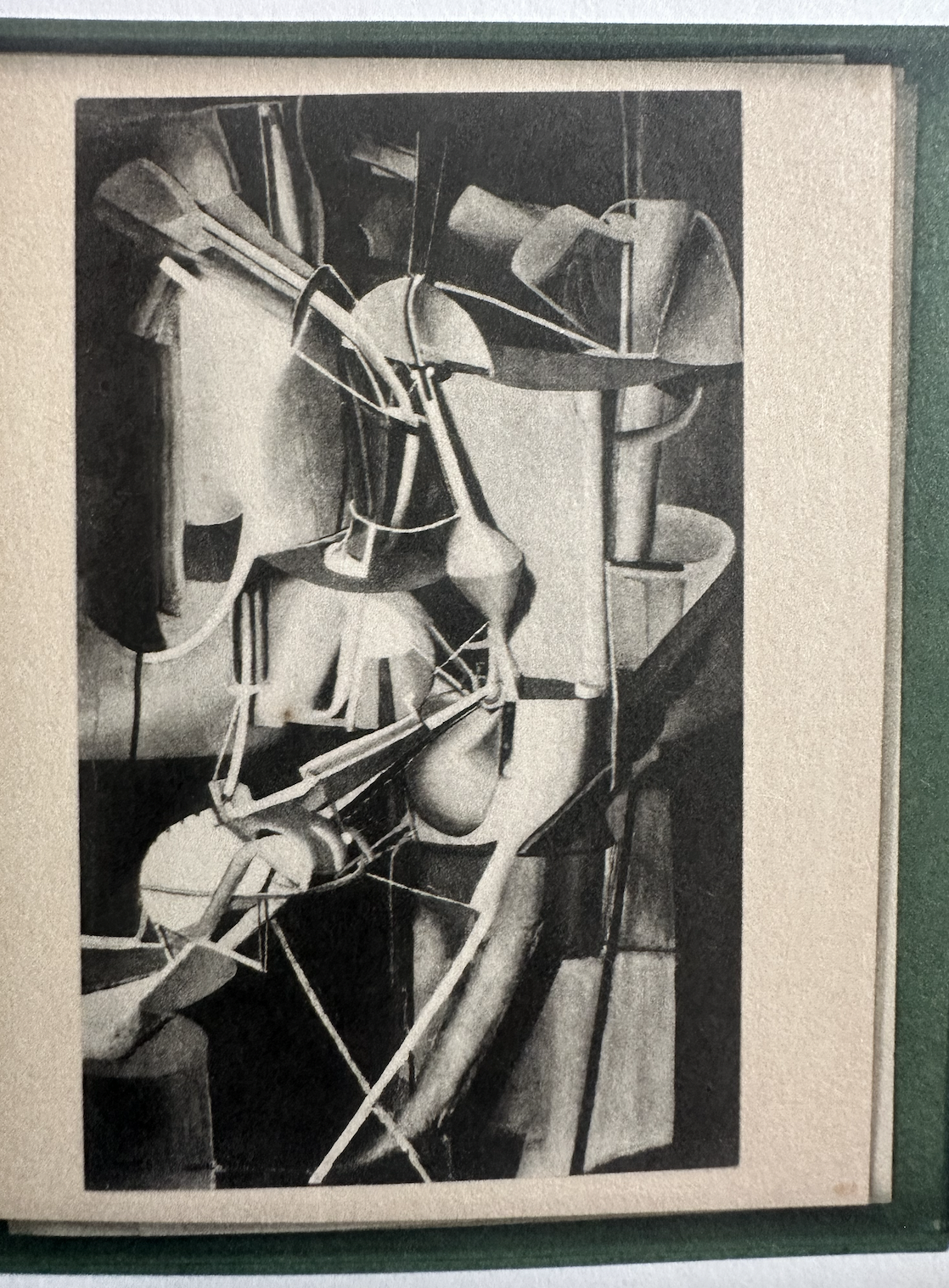

Delivered by the postal service earlier the week, a book as mesmerizing as the leaves the leaves falling from the trees along our street this week—- yellow for an instant and then smitten by asphalt — Earthly, a collection of Jean Follain’s poems translated by Andrew Seguin.

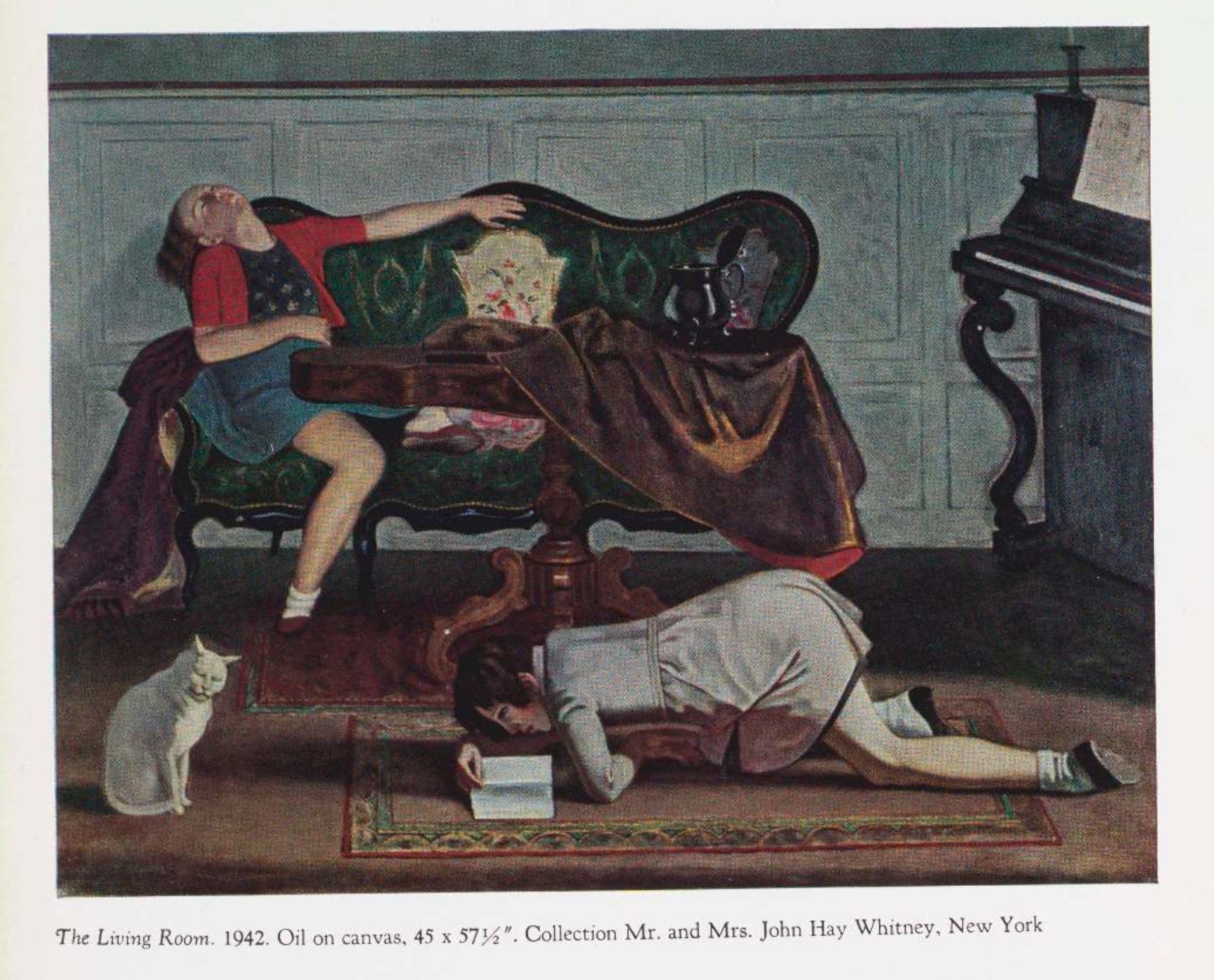

Camille Corot’s lithograph, The Gust of Wind (1871), sits lightly on the cover, gesturing towards Canisy, the small village in Normandy where the poet in question was born and fed bread. In the translator’s introduction, Seguin paints a portrait of his subject: this writer named Jean Follain who saw the agricultural lifeways of small towns gutted by the new economy of killing, the human looking for words in the wasteland following World War II, an event sponsored by governments who caused the mass death of young men and starved village economies of the labor required for their continuance.

When Follain says the horses have vanished, one can almost hear the absence of hoof-breaths on the hardened dirt roads, the odor of new chemicals replacing the scent of summer-warmed manure, a vanishing sensorium of rhythms and temporalities attuned to their own being. Follain’s poetry offers the rawness and complex vitality of these “remembered landscapes,” in Seguin’s phrasing, without the romance of the pastoral mode. Spoken in third person plural, the poems cull intimacy out of tenderness for details and actions rather than the expression of first-person feelings. The poems reveal the “simultaneity of remarkable things” — things which vanish and exist in the ordinary, things that disappear and reappear as spirits, things that linger in what Mahmoud Darwish called “the presence of absence.”

Countless poems lauding war’s victory have been written; it is more difficult to remind the reader of what such “victory” involved, and how the history of modern warfare has shaped the mechanized inhumanity of the present. Like Beckett, Follain wrote about the annihilation of Saint-Lô. As Seguin puts it: Follain’s “poems began to appear in journals alongside some of the Sagesse group, and the first of his thirteen books of poems, La Main chaude, was published in 1933. Prose works soon followed, including, in 1935, Paris, a beautiful flânerie of the city he made his home, and several memoirs of his childhood in Canisy and the nearby city of Saint-Lô, which was decimated by Allied bombs in WWII.”

The Gust of Gestures

What happens in Follain’s poems?

Things are touched. Things touch back. Subjects pause like objects in a dark painting. Children “dressed in black rags” scamper through ruins.” A man’s smile “vibrates” alongside the spike of wheat in his scythe. Snails sleep as the bread burns. “The protagonist of dreams” savors wine flavored by “myrtle and cypress” as alcohol fuels arguments in the pub. Doors creak through “cold rooms.” The “rustle” of poplars near rivers rouses the blood. A novelist studies the wandering vapors. A glass blushes like a continental sunset. The “already yellow” of lindens in July crosses paths with violins who are napping in their velvet-lined coffins.

In “Landscape of Rural Hardship”:

A small garden of chives

trembles beneath the stars.

The hardship is expressed in trembling of tiny chives.

Follain opens his “Eclogue” with a man in a “shattered house” who “plays at the game of existing” as the wind groans through the orchard. With no transition, Follain abandons the man for “the lightning-struck oak” where a bird perches on a limb, singing, unafraid, slowly morphing into a haunting image:

an old man has placed his hand

where a young heart

vowed obedience.

Gestures consecrate the movements in Follain’s poems.

The gesture of the old man’s hand touching the place where a young heart made a promise — vowed love or fidelity to an ideal or authority — lingers like the edges of a memory in the mind of the reader. This simultaneity in staging is what Follain perfected. This simultaneity gives his poems the feel of paintings as eloquent as an allegory by Gustave Courbet.

“Chovanne” is a poem-portrait of French royalist insurgent from the late 18th century. It opens “In the thick of the old world” with all its shadowed brocades and heavy textures of darkness (darkness is a fabric in the years prior to electricity) where a woman removes her “apparel” in order to look closely at her body “in the light.” Light is precious and she is the chovanne, thinking of her grey horse out back, “enclosed” to better serve “history and magic”. Follain moves between the woman’s thoughts (we imagine her smile) and the animal outside, using the shared vitality of heart and lungs to mark the life between them. They have survived, however briefly

and all that sky above them

would be the same for the assemblies.

The same for stupefying wars.

Hopefully, Earthly will introduce a larger segment of English-language readers Follain’s earth-rousing poems.

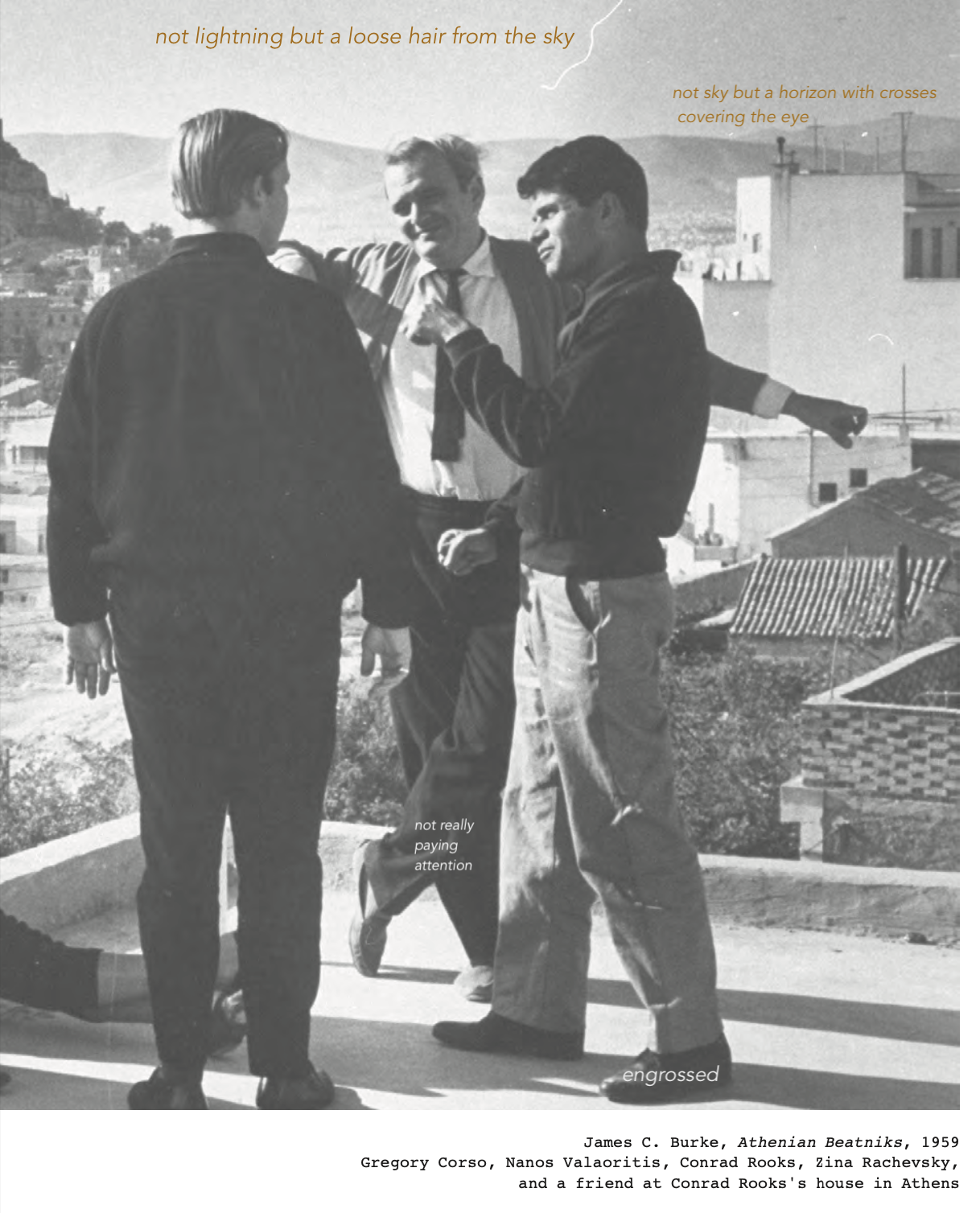

With goosebumps, I offer this one for the road, an ars poetica as text alongside the absented image of Jean Follain finidng words for the wind that unleafs the trees near the emptied homes and ruined lives of Saint-Lô.

History

As history seems

sad to the world at times

the heavy dinner gets cold

the great orator never returns

his mistress follows her dreams

later on

it's the uprooting

the muffled gunshots

the bells of a grand congress

on which night falls

while out in the fields

of his eternal childhood

the poet is walking

not wanting to forget a thing.

*

Alexandra Stréliski, “Plus tôt”

Camille Corot, The Gust of Wind (1871)

Jean Follain, Earthly translated by Andrew Seguin (Song Cave)

Leos Janáček, “A Recollection” (performed by András Schiff)

Samuel Beckett,The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989 (1995)