From the destroyed notebook:

(At the top margin, the word:) Nightmare -

(then disordered numbers, small, meaningless additions, then:)

— Rainer Maria Rilke’s blue notebook (translated by Mark Karnak)

These days rank among the most difficult....

Rilke realizes that he cannot possibly write, cannot find the necessary separation from life, while in Meline’s presence. So he sets off for Switzerland to stay in a pseudo-chateau and swears off contact for six months. His “Testament” collects straying thoughts as he tries to write, despite the presence of a loud mill nearby.

A poem from what would becomeThe Duino Elegies, written a decade prior, waits to encounter itself in others. “The aversion to what remains unfulfilled corrodes my body like rust, even sleep offers no relief —, half-awake, the blood pounds in my temples like heavy footsteps that refuse to rest,” writes Rilke, before turning to his absent interlocutor, and adding:

“If only I could call you… but that would destroy my last refuge — : this court where I recognize myself. You recently wrote that am not one who can be consoled by love. You were right. After all, what could be more useless to me than a life that allows itself to be consoled?”

”Striving & resisting: I am exhausted by it. Where is the heart that never 'insisted' on a stubborn happiness, but allowed me to prepare for it what springs inexhaustibly from me? Yet no consensus exists on this. Ah, if only the struggles would cease! If only we could hear as in the final stanza of Girard de Roussillon: Les guerres sont finies et les œuvres commencent. (The wars are over and the works begin.)”

Rilke is drawn to the gurgles and bubblings of a water fountain in the courtyard. True to form, he courts the inspiring on paper, noting how “the slightest breeze changed it, and when it was completely still around the suddenly isolated jet, cascading upon itself, it sounded quite different from the noise it made in the mirrored surface of the water.”

“Speak, I said to the fountain, & listened. Speak, I said, and my whole being obeyed it. Speak, you pure meeting of lightness and weight, you, the tree of games, you, a parable among the heavy trees of fatigue that fester within its cortex. And with an involuntary & innocent cunning of my heart, so that nothing would be but this, from which I wanted to learn to be, the distant, restrained, silent one.”

“If I did not resist the lover, it was because, among all the powers one can hold over another, hers alone, her unyielding power, appeared justified to me. Vulnerable and exposed as I was, I did not seek to evade her; yet I yearned to pierce her, to cross her boundary! Let it open a window onto the broader realm of existence... (not a mirror.)”

The lover and the writing exist in tension for the poet. Nothing will relieve or alter these intersections in his life— the duress of intimacy and its attendant conflicts. “Vulnerable and exposed” . . . like a man battered by winds on the cliffs near the Duino Castle, where his elegies would be finished.

Elsewhere, in an essay by Dan Beachy-Quick, there is a cliff that recollects the landscape near Trieste, the drift of Rilke’s Duino. Or there is my memory of this year’s cliff, the wind sweeping through rocks, a whistle crossing the surface of water. Yet— “(not a mirror.)”

I do remember a rose-bush growing on the edge of a cliff overlooking the sea, and a butterfly deep in a bloom; on the horizon a sailing ship seemed to move slowly from one flower to a next, a distance the butterfly crossed with but a few beats of her wings, while for the ship it took hours; I remember I wrote next to the passage love collapses subjective distances into a single span; but that page is hidden in a book hidden behind another book so that my own thought is a rumor I tell to myself.

I see I have been speaking again about books when I meant to speak about the ocean.

I see I have been speaking again about books when I meant to speak, about the ocean.

I see I have been speaking again about oceans when I meant to speak about sleep.

I see I keep saying you when I mean to say she, and say yours when I mean to say hers.

— Dan Beachy-Quick, from the essay of echoing cliffs

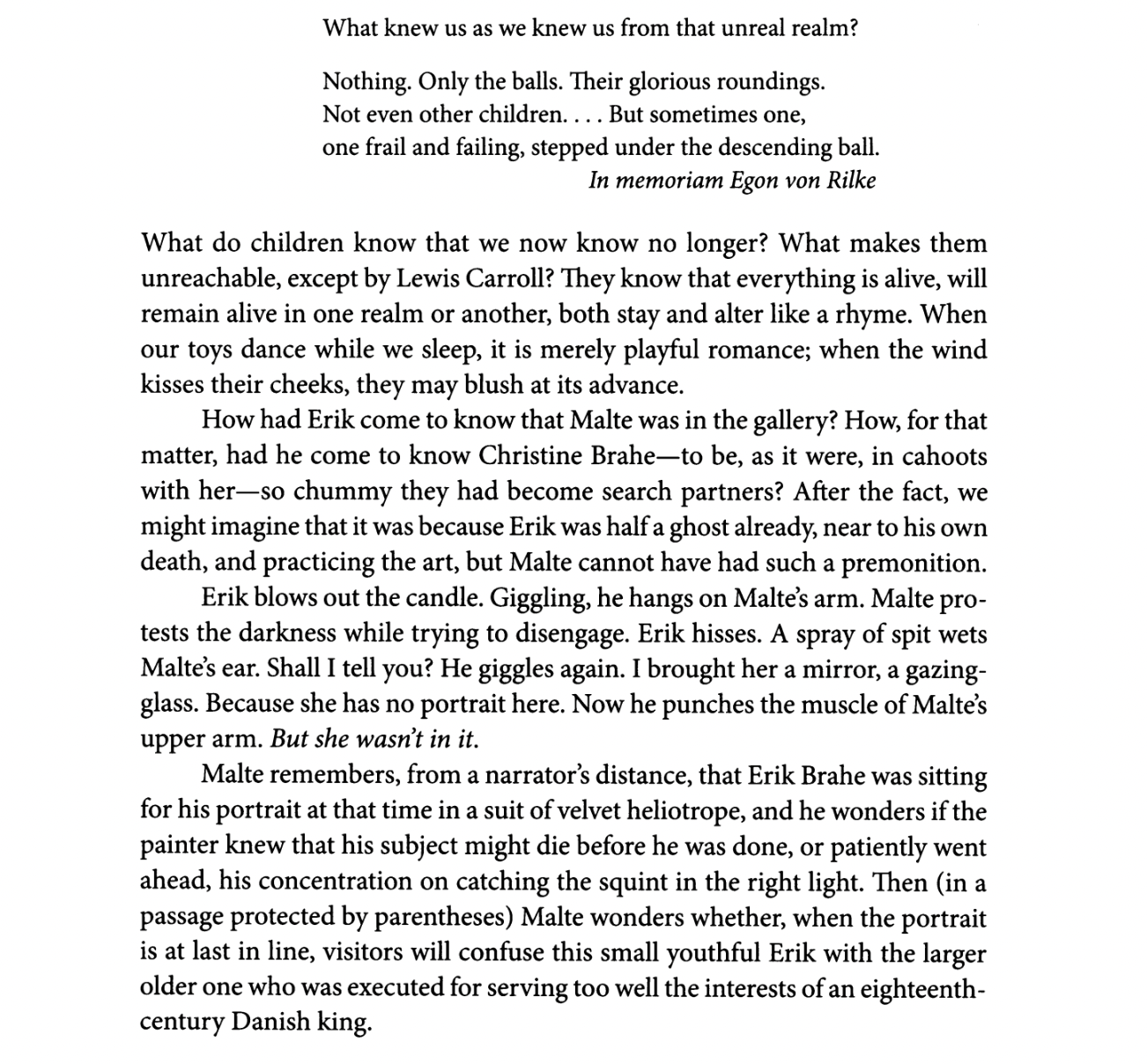

The great William Gass penned an unforgettable essay titled “Rilke and the Requiem” that inventories Rilke’s ghosts through his oeuvre. As an essay, it is immaculate— the sort of sweeping, mind-rattling work that only a devout student of Rilke could muster. We study what we love most: this is what it means to seek knowledge, to pursue its shadows through every syntactical loop and thematic cranny.

Like many such students, Gass translated Rilke’s poems in order to know him better, where better indicates knowing him well enough to risk speculating from that intransigent intimacy that births “my Wittgenstein,” “my Celan,” “my Gass,” “my Tsvetaeva,” etc.

Gass, then:

“Then (in a passage protected by parentheses),” Gass writes, enacting the protection as text, setting his words inside the familiar arms of those half-moon arcs that do not enclose the subject entirely — () — arms that embrace without creating a whole.

I have often mourned the parentheses’ failure to connect completely, or over-read an unassailable loneliness into those gaps —

(O how I . . . ) . . .

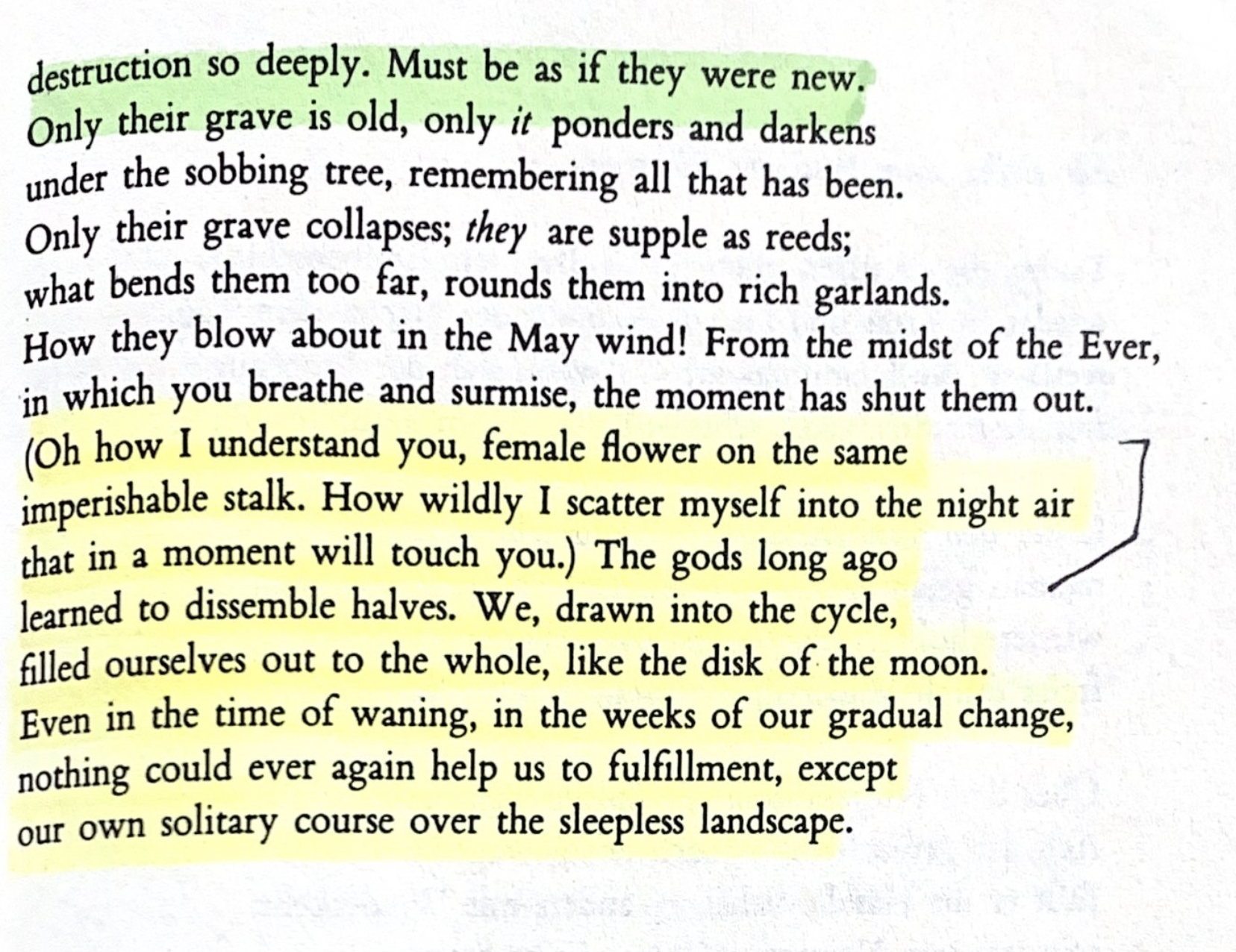

Among my three copies of Stephen Mitchell's Selected Rilke translations, there is one filled with color-markings, the text that peeks out from the rainbow of my Rilke readings. Yellow markings made in my 20's. Green arrived my late 30's during the nursing-while-returning-to-Rilke days. Rilke’s "Elegy” for Marina Tvsetaeva is a forever favorite in its form as well as its direction. His preemptive elegy to a friend would be matched by her own New Year’s elegy to Rilke, following the shock of his death.

It hurts to write. It hurts to not-write. This, too, is an unassailable rhythm that rocks the raft of a life.

(New page:)

return loved one diver bird's head cold sweat choker frost

vikuña ring-band trolley Liebknecht Agnese

— from the blue notebook that Rilke destroyed

*

Alfred Schnittke, “Die Geschichte Eines Unbekannten Schauspielers” (Schnittke, Film Music Vol. 1) as performed by the Berlin Symphony Orchestra

Dan Beachy-Quick, “Writing From Memory”

Gidon Kremer, “Oblivion”

Rainer Maria Rilke, “Elegy (for Marina Tsvetaeva-Efron)” as translated by Stephen Mitchell

Rainer Maria Rilke, The Testament & Other Texts (Contra Mundum Press), ed. by Rainer J. Hanshe, tr. by Mark Karnak

William Gass, “Rilke and the Requiem” (Georgia Review)