*

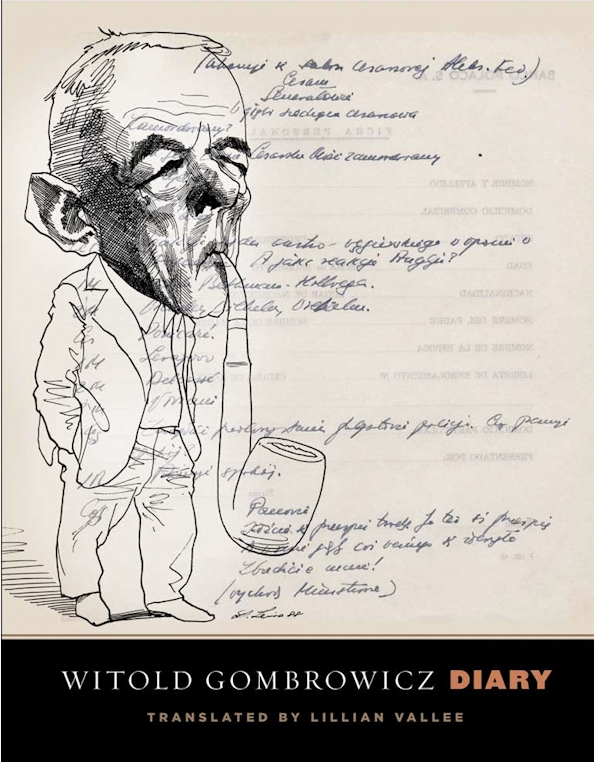

When returning to my notes on Witold Gombrowicz’s magnificent diaries this weekend, I came across an entry in 1954 that is given as two Sundays in a row. Not one Sunday that follows another but one Sunday that becomes many Sundays and then another Sunday that will be in the future. As an aside on chronology and the uses and self-abuses of selfhood in modern prose, I offer Gombrowicz’s two Sundays, excerpted from Gombrowicz’s Diary (as published through Yale University Press’ fantastic Margellos World Republic of Letter Series and translated by Lillian Valee) below.

Sunday

The cold wind from the south swept a mass of hot and humid air out of Buenos Aires and now it is blowing at a clip, howling, whistling, buzzing and slamming windows, throwing papers into the air at the intersections and causing real orgies of invisible witches. This pseudoautumn wind grabs me, too, and spurs me on into the past. It has the privilege of evoking the past in me and sometimes 1 submit to it for hours, sitting somewhere on a bench. There, blown through and through, I attempt something that is beyond my power but nevertheless ardently desired: contact with the Witold Gombrowiez from irretrievable epochs. I spend a lot of time reconstructing my past: I diligently establish a chronology and stretch my memory to its limits, looking for myself the way Proust did, but to no avail. The past is bottomless and Proust lies. Nothing, one can do absolutely nothing. Yet the southern wind, in causing certain upheavals in my organism, creates in me a state of almost amorous desire in which, desperately losing my way, I attempt to awaken my old existence in me for just an instant with a grimace.

On avenida Costanera, staring at the waves dashed into the air with relentless fury by the stone masonry of the shore, I, today's Gombrowicz, summoned that distant protoplast of mine in all of his tremulous and youthful vulnerability. Today, the triviality of those events took on (for me who already knew, who was now my own past, the solution to the riddle of that boy) the sanctity of legends about distant beginnings and today I knew the seriousness of that ridiculous suffering, I knew it ex post. I reminded myself, therefore, how one evening he-I went to the neighboring village of Bartodziei to attend a party, where there was a person who transported him– me into raptures and before whom I-he wanted to show off, shine. I-he needed this. Instead I walked into the salon and there, instead of admiration, l was greeted by the pity of aunts, the jokes of cousins, the crass irony of all those local landowners. What had happened? Kaden Bandrowski had “run down” one of my novellas in words that were actually full of indulgence but which categorically denied me any talent. That newspaper had fallen into their hands and they, of course, believed it because, after all, he was a writer and he knew what he was talking about. That evening I did not know where to hide my face.

If he-I was helpless in situations like this, then it was not at all because he was not up to them. On the contrary. These situations were irrefutable because they were unworthy of being refuted— they were too silly and frivolous to take the suffering that they caused seriously. You suffered and, at the same time, were ashamed of your suffering so that you, who at that time could easily handle far more menacing demons, broke down at this juncture, disqualified by your own pain. You poor, poor boy! Why hadn't I been at your side then, why couldn't I have walked into that drawing room and stood right behind you, so that you could have been fortified with the later sense of your life. But I—your fulfillment—I was—I am—a thousand miles and many years away from you and I sat—I sit—here, on the American shore, so bitterly overdue .. and thus, staring at the water that shoots up from behind a stone wall, filled with the distance of the wind speeding from the polar region.

Sunday

Today, years later, when I am a lot calmer, less at the mercy and the lack of mercy of judgments, I think about the basic assumptions of Ferdydurke regarding criticism and I can endorse them without reservation. There are enough innocent works that enter life looking as if they did not know that they would be raped by a thousand idiotic assessments! Enough authors who pretend that this rape, perpetrated on them with superficial judgments, any kind at all, is something that is not capable of affecting them and should not be noticed. A work, even if it is born of the purest contemplation, should be written in such a way as to assure the author an advantage in his game with people. A style that cannot defend itself before human judgment, that surrenders its creator to the ill will of any old imbecile, does not fulfill its most important assignment. Yet defense against these opinions is possible only when we manage a little humility and admit how important they really are to us, even if they do come from an idiot. That is why the defenselessness of art in the face of human judgment is the sad consequence of its pride: ah, I am higher than that, I take into account only the opinions of the wise! This fiction is absurd and the truth, the difficult and tragic truth is that the idiot's opinion is also significant. It also creates us, shapes us from inside out, and has far-reaching practical and vital consequences.

Criticism, however, has yet another aspect. It can be seen from the author's side but it can also be seen from the side of the public and then it takes on even gaudier tones of scandal, mendacity, and deception. How do these things look?

The public desires to be informed by the press about books that appear. This is the source of journalistic criticism, manned by people having contact with literature.

Yet if these people really had something to do in the field of art, if they really were rooted in it, they certainly would not stop at these articles. So, no, these are practically always second- and third-rate literary figures, persons who always maintain merely a loose, rather social, relation with the world of the spirit, persons who are not on the level of the concerns that they write about. This then is the source of the greatest difficulty, which cannot be avoided and from which arises the entire scandal that comprises criticism and its immorality. The question is the following: How can an inferior man criticize a superior man, how can he assess his personality and arrive at the value of his work? How can this take place without becoming absurd?

Never have the critics, at least the Polish ones, ever devoted even a single minute of time to this delicate matter. Mr. X, however, in judging a man of Norwid's class, for example, puts himself in a suicidal, impossible position because in order to judge Norwid, he must be superior to Norwid but he is not. This basic falseness draws out an infinite chain of additional lies, and criticism becomes the living contradiction of all of its loftiest aspirations.

So they want to be judges of art? First they must attain it. They are in its antechamber and they lack access to the spiritual states from which art derives.

They know nothing of its intensity.

So they want to be methodical, professional, objective, just? But they themselves are a triumph of dilettantism, expressing themselves on subjects that they are incapable of mastering. They are an example of the most unlawful usurpation.

Guardians of morality? Morality is based on a hierarchy of values and they themselves sneer at hierarchy. The very fact of their existence is in its essence immoral: there is nothing that they have exhibited and they have no proof that they have a right to this role except that the editor allows them to write. Giving themselves up to immoral work, which consists of articulating cheap, easy, hurried judgments without basis, they want to judge the morality of people who put their life into art.

So they want to judge style? But they themselves are a parody of style, the personification of pretentiousness. They are bad stylists to the degree that they are not offended by the incurable dissonance of that accursed "higher" and "lower." Even omitting the fact that they write quickly and sloppily, this is the dirt of the cheapest publicism. ...

Teachers, educators, spiritual leaders? In reality, they taught the Polish reader this truth about literature: that it is something like a school essay, written in order that the teacher could give it a grade; that creativity is not a play of forces, which do not allow themselves to be completely controlled, not a burst of energy or the work of a spirit that is creating itself but merely an annual literary "production," along with the inseparable reviews, contests, awards, and feuilletons. These are masters of trivialization, artists who transform a keen life into a boring pulp, where everything is more or less equally mediocre and unimportant.

A surplus of parasites produces such fatal effects. To write about literature is easier than writing literature: that's the whole point. If I were in their place, therefore, I would reflect very deeply on how to elude this disgrace whose name is: oversimplification. Their advantages are purely technical. Their voice resounds powerfully not because it is powerful but because they are allowed to speak through the megaphone of the press.

What is the way out of this?

Cast off in fury and pride all the artificial advantages that your situation assures you. Because literary criticism is not the judging of one man by another (who gave you this right?) but the meeting of two personalities on absolutely equal terms.

Therefore: do not judge. Simply describe your reactions. Never write about the author or the work, only about yourself in confrontation with the work or the author. You are allowed to write about yourself.