Restraint deepens passion by refusing to give it easy vent.

— Garry Willis, Lincoln of Gettysburg

I take androgyny for granted in everyone.

— Harold Brodkey, “Translating Brando”

NOTE ON “POSITION”

Like Pierre Guyotat in his table-less studio in Passy, I write with my notebook pressed against my knees, the scent of dust in the corners of the hardwoods, transfixed by the sculpted eros of the unswept. This position is ordinary for me: a repetition, a motion that involves returning to a familiar place and position, in order to ascertain what has changed. With my notebook in my lap and the couch behind my back, I reconvene the scene of small details.

Notice— the new dog bone under the gray sofa, the vine strangling the birdfeeder near the window, the virulent green of the man’s pants in the framed drawing, an undated pastel piece that escaped time’s signature. It is this green on my wall that calls to the green parrot in Pierre Guyotat’s Idiocy.

Green pants to the green parrot who recites its repertoire of apartment sounds in the scene where Guyotat helps an elderly woman write the detective novel she has dreamed.

The parrot recites (or cites again,re-citing being another way of re-saying): the elder’s cough, “the creaking floors, the hubbub of voices on the avenue, the paintbrush twirling in its pot, my footsteps” — cut by the flashback of twins’ sexual escapades.

The woman holds her paintbrush, just as she has held it for many years and offers him “her other hand” which he kisses as he has done since “tall enough to do so.” The narrator returns to the woman’s text, which must be set on a particular street “where she passed one night during the interwar years in a taxi taking her home from a Boulevards theater with her husband, also a rentier.” This is the ride the woman wants to continue: to go from there, where a protest halted their taxi near the oysterman she can’t forget. This the scene she returns to sketch, now that her husband cannot prevent her from imagining the mystery, or inventing an amorous intrigue with “his young, half-niece from Brittany.”

The writer types the woman’s words onto paper and a “new phrase” appears, a phrase that ends with a flourish “which delights her.”

“At the heart of love”: he types it.

The parrot repeats the woman’s words but the writer’s ear hears: “the hurt of love, the hurt of love” – and the dance between monosyllabic near-homphones (heart, hurt, heart, hurt) continues as he repeats the conventional act of closure at the end. “The hand re-kissed, the thing half- written, the story interrupted by the murmur of faraway water and “half-light” on the street outside.

The re-petition. (To petition again.)

The seasons recur (return, recurve) in stories of phosphorus–the mark of early spring when leaves turn dark green and then deepen into purple as they grow deficient in phosphorus, a mineral that isn’t available or active in cold, wet soil. The first signs of warming beneath us involve this darkening of the leaves.

NOTE ON PARROTS

Mornings inch towards autumn only to be defeated by the dry heat which conquers the front porch by afternoon. This is the weather of the week, a background of sorts. And Guyotat’s heart/hurt — his Kierkegaardian distinction between the said/heard— returns on an afternoon when I find myself studying Auguste Renoir's paintings with one of the teens.

We agree that Renoir makes sumptuous use of black paints . . . BLACK, on his canvas, is a charged enigma, offering itself as a bridge between foreground and background.

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Woman with Parrot (1871)

Amid this orgy of deep blacks, I pause near Woman With Parrot, Renoir’s portrait of Lise Tréhot. She is holding a small green parrot in an elegant room, her pointer finger flush against the bird’s head. The fern to her right is given in a loud green, a rakish, vaguely-decadent green that draws attention away from the yellowish-green of the parrot.

My eye inclines to Renoir’s signature, placed neatly beneath the fern in a small oval on the carpet, as if to remind the viewer that color is a discipline. Color is how Renoir tames the scene. When I remove my glasses, the painting appears as from a distance, forcing me to consider his distribution of color. Forest green fronds on the wall; green patterns set atop grey on the wallpaper. Renoir’s greens draw the eye upwards from the fern to the ceiling. But Renoir’s reds draw the eye downward from the ribbons to the floor, down towards those marooned splotches covering the carpet. A sickly yellowish-green occupies the center, linking the cage to the parrot and the olive undertones of Lise’s skin.

Lise appears in at least 16 of his canvases during the six-year period when she and Renoir were companions. This painting was finished in 1871. In April of the following year, Lise married wealthy architect and never set eyes on Renoir again.

Certainly, he resented this. In a letter dated from March of 1912, Renoir downplayed the significance of this painting. He relegated Lise to a lost sight, a thing no longer given to his seeing. “I’m returning the photographs of the two paintings along with this letter,” Renoir wrote, adding that “The Woman with Parrot must have been done. . . in 1871 at the latest, because after this time I lost sight of the woman who posed for this picture.” Either way, Renoir continues, the paintings “are of no value, especially the Woman with Bird [sic].”

Colors and pictures on paper. Juvenilia.

“Pray do not get too excited over such daubs,” Renoir advises his correspondent.

The bright red of Lise’s necktie align with the gash of red ruffles pouring from back of her black dress, lending a dignity and respectability to the scene at this precise moment when she refuses our interest, electing, instead, to offer herself entirely to the bird in her hand. Aloof— but not really pensive so much as eager to withhold her attention from the painter? One wonders what thoughts whisk through the decidedly-hidden interior.

According to the Guggenheim Museum, genre paintings of the 1860s and 1870’s often featured “richly dressed young women” who were assumed to be “lorette, or high-class courtesans.” In these genre paintings, “the parrot and the gilded birdcage are sometimes interpreted as erotic symbols.” The way Renoir leans into this genre might have upset Lise as she sought to varnish her reputation for a marriage into the ruling classes.

The Guggenheim also mentions that the subject of woman holding parrot “appears in works from the 1860s by Gustave Courbet, Edouard Manet, and Edgar Degas,” a statement clearly worded as an encouragement to share one of my favorite parrot-themed portraits, namely Gustave Courbet’s Woman with a Parrot.

Gustave Courbet, Woman with a Parrot (1866)

The woman in this painting hides nothing from the parrot. Like Renoir’s woman, her interest is given entirely to the bird on her hand — but the expression is one of fascination rather than disdain. Her fingers are spread open, resembling the gesture of a statue I saw last week in New Orleans: a posture of the hand that beckons winged things. And the parrot complies. In Courbet’s painting, the walls are tent-like, set to sway and curve like the fabrics beneath the nude: the distance between inside and outside is permeable, as illustrated by the slight crack in the wall — with its chlorophyll-warmed greens — that enabled the parrot to enter. Courbet’s parrot is an expected guest who visits and delights the woman. Renoir’s parrot is a caged creature intended to please the residents of the cultivated bourgeois interior. I could riff on this forever . . .

NOTE ON THE BOOK, ITSELF

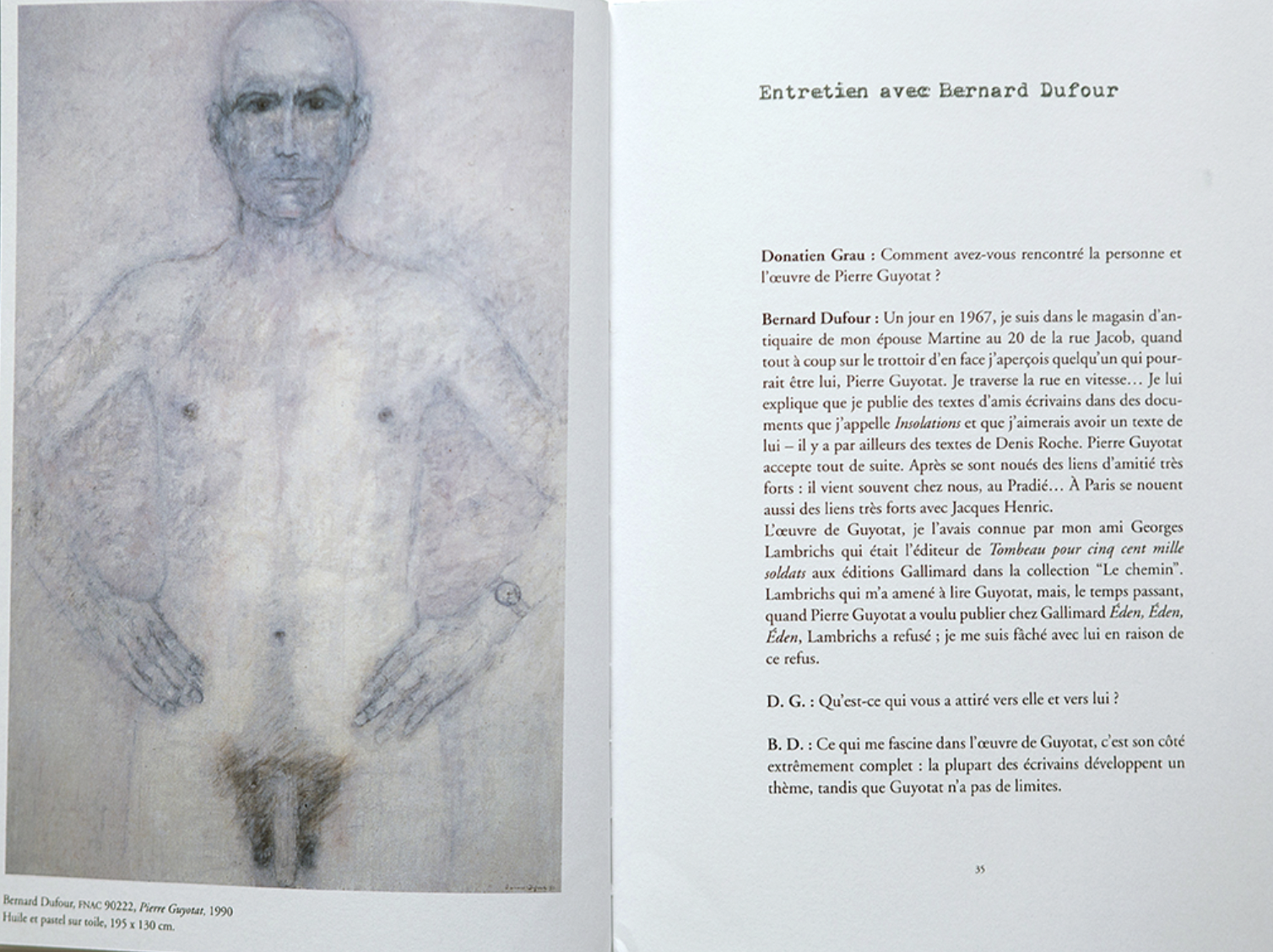

My diversion into Guyotat’s green ignores one of the primary themes in his work, namely, his experience in Algeria, where he discovered his own solidarity with the anticolonialist struggle of Algerians. HisTomb for 500,000 Soldiers (1967) was based on these experiences and scandalized the French reading public with its depictions of war, servitude, and sexuality. Idiocy traces a similar space: its most riveting parts occur later in the book, in a testament of the atrocities he witnessed as a French soldier in the Algerian war. Guyotat details his own arrest for inciting desertion as well as his three-month imprisonment in a hole in the ground. Where mystics sought solitary confinement as a means to apotheosis, Guyotat learns nothing from the hole. He is not transfigured or redeemed.

When Edmund White called Guyotat “one of the few geniuses of our day,” he was not lying. Idiocy’s searing condemnation of colonialism and militarized violence implicates its speaker. In refusing social constructions of personal innocence, Guyotat writes against himself, against his culture and the cult of ‘decent men’. His sentences wind through the mind like those of a Proust who dared pledge his fides to a queer icon of Saint Sebastian.

I must keep quiet for a little space and then walk very slowly along that bright sound of pain, towards that blue, blue wave. What bliss there is in blueness. never know how blue blueness could be.

– Vladimir Nabokov, Laughter in the Dark

*

Claude Debussy, Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien: Fragments Symphoniques (1911)

Gustave Courbet, Woman with a Parrot (1866)

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Woman with Parrot (1871)

Pierre Guyotat, IDIOCY, tr. by Peter Behrman de Sinéty (NYRB Classics, 2025)

“Pierre Guyotat Reading Matter Pt. 1” a feature from CABINET

Fondation Azzedine Alaia, from the catalog titled Pierre Guyotat, la matière de nos œuvres