The first week they wrote a letter.

He wrote it.

She thought about it.

Peace was in the house like a broken staircase.

— Robert Creeley, “The Interview”

What is the point. That is what must be borne in mind. Sometimes the point is really who wants what. Sometimes the point is what is right or kind. Sometimes the point is a momentum, a fact, a quality, a voice, an intimation, a thing said or unsaid. Sometimes it's who's at fault, or what will happen if you do not move at once. The point changes and goes out. You cannot be forever watching for the point, or you lose the simplest thing: being a major character in your own life.

— Renata Adler, “Brownstone”

1

“Where to begin.”

To quote Renata Adler.

To start with the favorite, or one of the favorites, or the favorite at 2:13 p.m. in the week of Robert Creeley’s For Love: Poems 1950-1960.

To refuse to think about these poems in the order they are given.

To choose, instead, the unscrupulous preferences of one’s own exuberance, one’s own tonalities, one’s own stammering speculations.

To be small, then. Small as this spare poem that spares us nothing.

A creature of three stanzas that reassures the extra line of its role as tiny ruiner. 3-3-4, the extra word.

The Rhyme

There is the sign of

the flower—

to borrow the theme.

But what or where to recover

what is not love

too simply.

I saw her

and behind her there were

flowers, and behind them

nothing.

To move into “The Way,” and notice the way a tone of conclusiveness undercut the speaker’s claims and abrades his putative ego.

To admire the riffing on Shakespeare’s famous sonnet, creating a dialogue with that particular strain of romantic bravado . . .

The Way

My love’s manners in bed

are not to be discussed by me,

as mine by her

I would not credit comment upon gracefully.

Yet I ride by the margin of that lake in

the wood, the castle,

and the excitement of strongholds;

and have a small boy’s notion of doing good.

Oh well, I will say here,

knowing each man,

let you find a good wife too,

and love her as hard as you can.

To go from this difficulty, this impossibility, with its “small boy’s notion of doing good,” back to the lake and the lack and the riffing on emblematic lines from poetry as a way into the poem:

The Bed

She walks in beauty like a lake

and eats her steak

with fork and knife

and proves a proper wife.

Her room and board

he can afford, he has made friends

of common pains

and meets his ends.

Oh god, decry

such common finery as puts the need

before the bed, makes true what is

the lie indeed.

”Laughter releases rancor the quality of mercy is not / strained,” as Creeley reminds in the droll seriousness of “The Crisis” — there is the collective resilience of laughter.

2

To see things differently in a white dress.

To admit the frame in the framing of it.

To move into the openly-sacrificial gesticulations of “A Marriage,” with its sombre tonality, an accomplishment of syntax and declarative hints.

To study the connotations and flexing of this legal word, retainer, even as it develops from the traditional “first time, second time, third time” punchline to the classic storyteller-style joke or else the fable:

A Marriage

The first retainer

he gave to her

was a golden

wedding ring.

The second—late at night

he woke up,

leaned over on an elbow,

and kissed her.

The third and the last—

he died with

and gave up loving

and lived with her.

To consider the trinitarian impulse in triples, and the human belief that magic occurs in numbers.

To be one two three about things.

To speak of pain in relation to form, where eternity is the duration of that see-saw between existence and penitence, as in “The Letter”:

The Letter

I did not expect you

to stay married to

one man all your life,

no matter you were his wife.

I thought the pain was endless—

but the form existent,

as it is form,

and as such I loved it.

I loved you as well

even as you might tell,

giving evidence

as to how much was penitence.

To feel slightly medieval when reading him.

To extend lais-like thought into something lighter. A gist in Creeley’s marriage and courtship poems reaching back loosely towards medieval fabliau (plural: fabliaux), that species of brief and bawdy tale that made use of satire to challenge clergy, women (as femininity), and marriage, wherein humor develops from plot through an intrigue or practical joke told in a rapid succession of events that form a single episode. Narrated in eight-syllable rhyming couplets, fabliaux were very popular in France during the Middle Ages. The effectiveness of the fabliau depends on the recognition of cultural cues and behaviors that point to easily discerned conceptions of human nature and gender. This type of literary form recurs throughout Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and Boccaccio's Decameron, where it is not limited to rhyming couplets. Clearly, Creeley isn’t playing the by the rules of the fabliau in these poems, but he seems familiar with the form, perhaps culling its rhetorical strategies when drafting poems like “A Marriage.”

To stand back from the particulars.

To glance downwards with the eye of the bird, noting how his use of adynaton, the “not possible,” lays bare love’s rhetorical strategies and hyper-magnifications. Say my love burns like a hundred suns. Say heart throws itself into the headlights. Say my superlatives stack up in his “Ballade of the Despairing Husband”:

Oh lovely lady, morning or evening or afternoon.

Oh lovely lady, eating with or without a spoon.

Oh most lovely lady, whether or dressed or undressed or partly.

Oh most lovely lady, getting up or going to bed or sitting only.

Oh loveliest of ladies, than whom none is more fair, more gracious, more beautiful.

Oh loveliest of ladies, whether you are just or unjust, merciful, indifferent, or cruel.

Oh most loveliest of ladies, doing whatever, seeing whatever, being whatever.

Oh most loveliest of ladies, in rain, in shine, in any weather.

Say any working-poet can sympathize with the rhyming couplet that concludes this “Ballade”:

Oh lady grant me time,

please, to finish my rhyme.

3

To consider the way he uses a comma.

To push his commas away and look for the sharpened points of his periods.

To say: if you.

To think: if then.

To read “If You” closely as if to resolve whether the repetition can offer closer.

To mean: I’m not sure how I feel about the repeating couplet that book-ends the conditional.

To admire the poem’s construction from a simple conditional, where the marital crisis involves a pet . . . and the bow touches the violin in the second-to-last couplet, with the crisp serial of monosyllabic words:

Dead. Died. Will die. Want.

Morning, midnight. I asked you

if you were going to get a pet

what kind of animal would you get.

To know and not know.

4

To study the material, itself.

To consider Robert Creeley’s intent when he said: “Things continue, but my sense is that I have at best, simply taken place with that fact... So it is that what I feel, in the world, is the one thing I know myself to be, for that instant. I will never know myself otherwise. Intentions are the variability of all these feelings, moments of that possibility. How can I ever assume that they come to this or that substance?”

To be apprehended by the mirror on the stream’s reflective surface in “The Awakening" —like the smallness of the man rubbing the myth from his eyes, reckoning with seeing “his size with his own two eyes” in the dark water.

To move through the locutionary ache of “The Tunnel,” with its variations and degradations of loneliness and echo . . . “time isn’t.”

The Tunnel

Tonight, nothing is long enough—

time isn’t.

Were there a fire,

it would burn now.

Were there a heaven,

I would have gone long ago.

I think that light

is the final image.

But time reoccurs,

love—and an echo.

A time passes

love in the dark.

To note how three returns in the tunnel’s structure: those three stanzas doing the work of completion, not by ordinary standards but through the sleight-of-hand that evokes our inarticulable expectations.

To see these threes in Creeley’s heroes.

To note this three-stanza poem, each quatrain quivering with Creeley’s extraordinary enjambment, the way he imposes rupture within a breath, where imposing plays into “possibility,” and reminds the reader of its kinship with the pose, which is to say, the hero, the poet, the sibyl, the speaker, the meteoric mythos:

Heroes

In all those stories the hero

is beyond himself and into the next

thing, be it those labors

of Hercules or Aeneas going into death.

That was the Cumaean Sibyl speaking.

This is Robert Creeley, and Virgil

is dead now two thousand years, yet Hercules

and the Aeneid, yet all that industrious wis-

dom lives in the way the mountains

and the desert are waiting

for the heroes, and death also

can still propose the old labors.

No heroes can rest without imagining the singular. Even if the singular only exists as a frame for the lack that imagines a partner.

The logic of lack commits “Heroes” to a pseudo-companion, a poem titled “The Hero” — the first stanza smattered with internal slant rhymes that create a beat or sense of motion, as in:

Each voice which was asked

spoke its words, and heard

more than that, the fair question,

the onerous burden of the asking.

And then further, in the same poem, once again, there is the suppleness of Creeley’s enjambment, the fractures of motion he uses to build these discrete stanzas, carriers of framed images:

Go forth, go forth,

saith the grandmother, the fire

of that old form, and turns

away from the form.

To study what form solicitates.

To sit on his simple hill and be aware of its shape:

5

To sit on that hill for hours with my dog, Radu.

To spy another hero in the valley from these heights.

To then descend, headily, into the transposition — or the images recollected, the outlines composed by Wallace Stevens in that extraordinary poem titled “Examination of the Hero in a Time of War” —

It is not an image. It is a feeling.

There is no image of the hero.

There is a feeling as definition.

How could there be an image, an outline,

A design, a marble soiled by pigeons?

The hero is a feeling, a man seen

As if the eye was an emotion,

As if in seeing we saw our feeling

In the object seen and saved that mystic

Against the sight, the penetrating,

Pure eye. Instead of allegory,

We have and are the man, capable

Of his brave quickenings, the human

Accelerations that seem inhuman.

To wonder (again) about the concept of “innate music” in poetics.

To re-read a letter written by Wallace Stevens in 1936, when he was working on “The Man With the Blue Guitar,” and theorizing the imagination’s influence.

To read the words of Stevens’ letter aloud in the room of this instance, this Now.

“The validity of the poet as a figure of the prestige to which he is entitled, is wholly a matter of this, that he adds to life that without which life cannot be lived, or is not worth living, or is without savor, or in any case, would be altogether different from what it is today,” said Stevens.

To pause and look up at the overwatered house plant.

To return to Stevens’ letter, and resume my chlorophyll-adjacent reading: “Poetry is a passion not a habit. This passion nourishes itself on reality. Imagination has no source except in reality, and ceases to have any value when it departs from reality. Here is a fundamental principle about the imagination; it does not create except as it transforms. There is nothing that exists exclusively by reason of the imagination, or that does not exist in some form in reality. Thus reality = the imagination, and the imagination = reality. Imagination gives, but gives in relation.”

To acknowledge the italics above as my own — just as this relational imaginary, wherein imagination alters the relations we form with experience, and this alteration is what we carry forward as influence, belongs (somehow) to Stevens.

And to end with perhaps a favorite —

6

— followed by a talisman, a mirror, an echo.

A Token

My lady

fair with

soft arms, what

can I say to

you—words, words

as if all

worlds were there.

— Robert Creeley

When it happens you are not there

— W. S. Merwin, “To the Words”

And you my future constellation

climb up in the sky with me

— Morphine, “Like a Mirror”

To Make a Cento of It

“I’m thinking of that charming phrase: what goes around comes around.”

— Robert Creeley to Bruce Comens

i

House. Your hand is an iron

shovel looking down at me.

Night comes. We sleep.

In hell we will tell of it.

ii

The door to the pantry

in Virgil’s plan is a poem

for the ways of water.

All eyes as if talking — taking

always the beat from the

breath it must have been.

Yielding manner as

simply as that syntactic

accident. The moon

is white in the branches

as we climb the hill for our picnic

I see a face appear.

Kenneth Patchen is hunting deer

inside Russia, too far from

me. . . the nightmare.

You on your back with your

Robert Creeley.

iii

Viz: hey.

Nothing for You is untoward.

Tree, speak. I will be a romantic.

I will sell her hands, her hair, her eyes, all things time isn’t—

cruel instrument.

iv

It is a viscous

form of self-

like flowers

thrown under

their colors.

What I took in my

hand: a man,

a direction — I am.

All beggar.

As if all that

surrounds her

as hair be also

today — a double

flute. To

walk

at night.

The trees — goddamn

them, the galloping

collection of greens,

subservience. I am.

All ears.

Be for me

like rain—

a being nothing

and there.

v

At night, there are other things white in the mind of it.

I took in my hand the possibility cut so small in the wall where you spoke to me.

Were there a fire it would burn now for the sake of the tree.

*

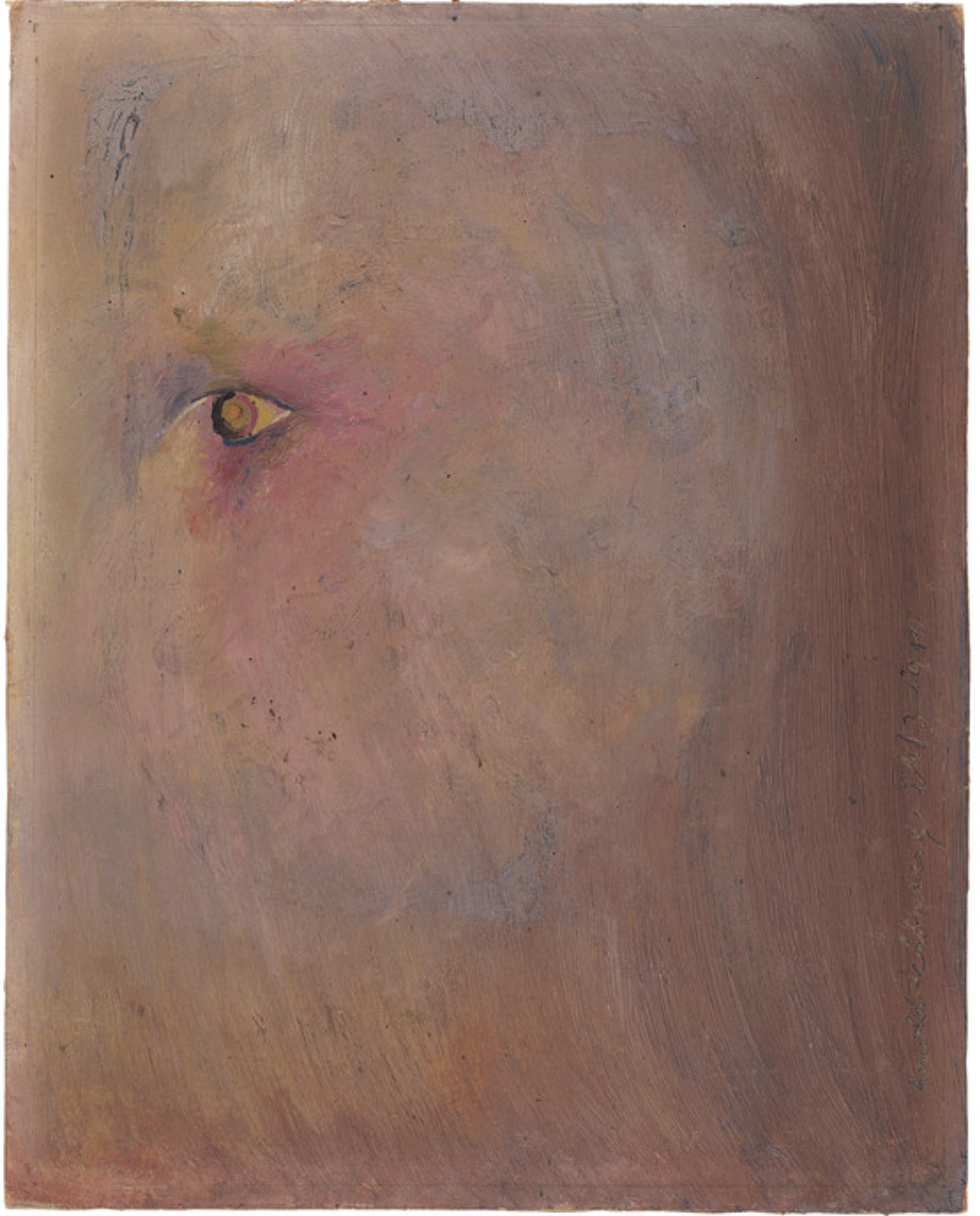

Arnold Schoenberg, Red Gaze (1910)

Bruce Comens, “A Conversation with Robert Creeley by Bruce Comens” (The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Fall 1995)

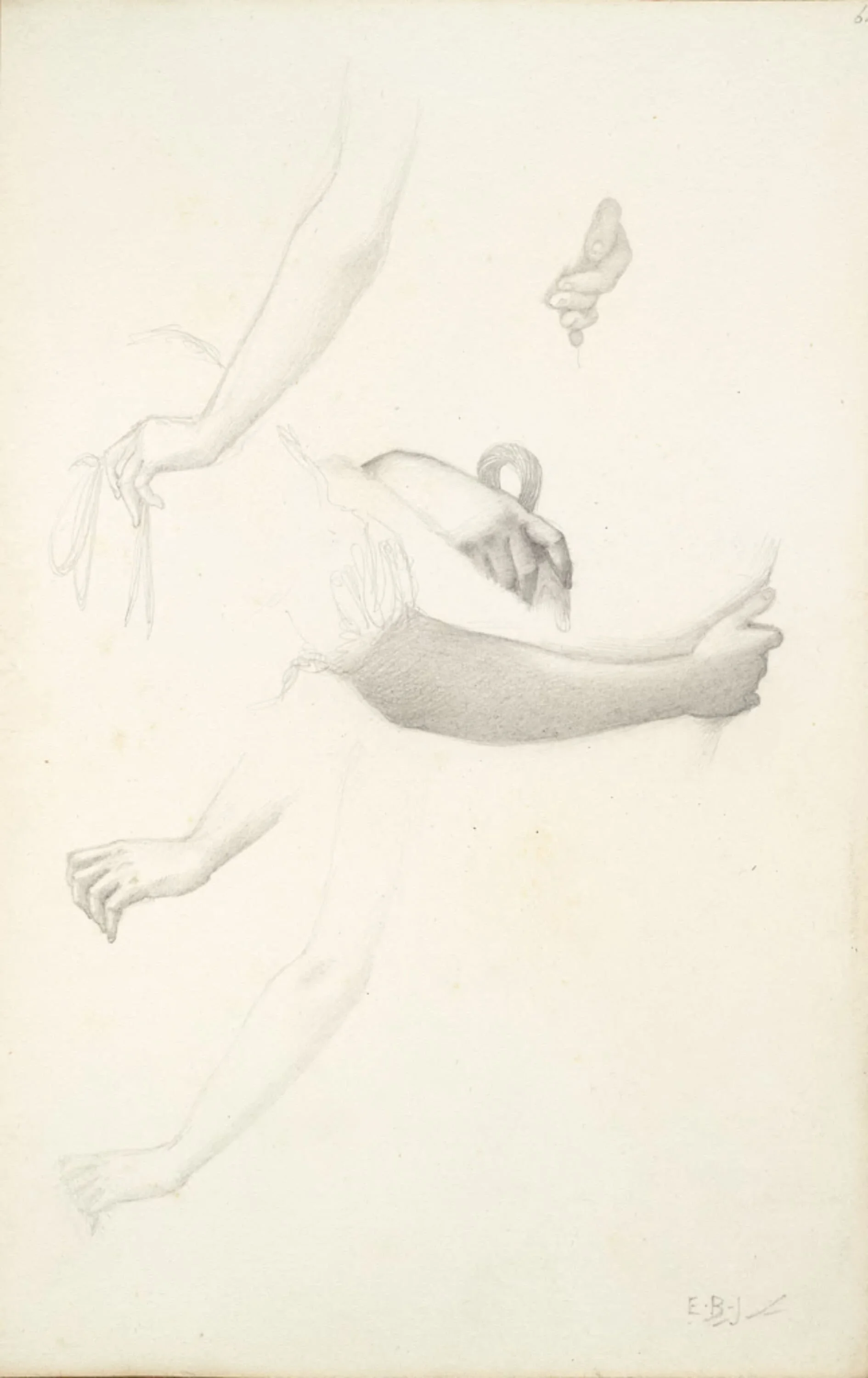

Edward Burne-Jones’s sketchbook (Harvard Art Museum)

Max Richter, “Psychogeography”

Morphine, “Bo’s Veranda”

Morphine, “Like a Mirror”

Renata Adler, Pitch Dark (NYRB Classics)

Robert Creeley, For Love: Poems 1950 - 1960 (PDF)

Robert Creeley, “To Say It”

W. S. Merwin, “To the Words”

Wallace Stevens, “Examination of the Hero in a Time of War”