We want fire; a little less mutton and a little more genius.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

As I stood waiting, a scene from Kafka’s Trial flashed through my mind—with the help of a washerwoman, Josef K. gets to see what is in the judge’s law book: pornographic drawings.

Dimitris Lyacos

Is this not literature pleading guilty?

Georges Bataille after reading Lautréamont

/ hatred of poetry no. 9

In the summer of 1912, Franz Kafka and Max Brod took and trip to Weimar and visited the Goethe House and the Goethe-Schiller Archive. According to custom, the guest book lay open beside the front door. As he prepared to sign his own name, Kafka recognized the signature of novelist Thomas Mann. It seems that Kafka studied Mann’s signature and then opened his notepad to re-render the curves and sinews of Mann’s lettering. The notepad includes shorthand descriptions and key words from Kafka’s Weimar excursion, as well as his “forgery” of Mann’s signature— which he promptly crossed out. Kafka’s decision to scribble over the signature may have been a way of expressing his feelings about 1) the failure of the forgery 2) the failure of the man named Thomas Mann 3) the failure of the forger’s whim 4) the failure of the author’s forger 5) the death of the author as Other 6) boredom, contempt, or any human state Alberto Moravia used as a title for one of his novels. Beneath Kafka’s forgery of Mann’s signature sits “as a digital reconstruction of the signature without his cross-out,” as rendered in a book by Reiner Stach. The digital reconstruction opens a different story about authorial death and forgery. According to Stach, Thomas Mann’s signature in “the original” guestbook has never been located.

/ hatred of poetry no. 4

* Point of clarification, with gratitude to James Marcus, who noted on twitter that “Updike's father was a small-town schoolteacher and after his childhood in Shillington the future author lived in a small farmhouse with his parents and grandparents.” Updike came from a stable, loving, supportive family and attended Harvard on full scholarship. “Also, his mother was a writer and so his literary aspirations were respected from the beginning.” The third John may not have needed to pay for college, which is a good thing— a thing that should be the case for all students.

/ hatred of poetry no. 8

Heinrich Marx fumed as he paced across the freshly-swept floors of his home. His son, Karl, had been sucked into the fever of romanticism. He was wasting his life on poetry. Determined to reason with his son, Heinrich agreed that poetry was an art worthy of consumption — memorizing and reciting poems could even elevate a fellow’s social standing among peers — but, for gentleman, poetry could only be a noble side-stint, relegated to moments of leisure. Poetry, said Heinrich, was perfectly cultured activity as long as it remained marginal to a career in law. Among the bourgeoisie, the poet could only be a hobbyist. (Centuries later, Heinrich’s view is shared by most middle-class American professionals.) Nevertheless, despite his father’s harangues, the rankled young poet named Karl persisted in versifying. Perhaps his father’s careerist hectoring drove the son even more deeply into the realm where poetry constitutes rebellion? Perhaps Marxism owes its a splinter of its existence to the chip that bloomed on Karl’s shoulder vis a vis his father? Leaning on the conventions of Heine's Book of Love (1827), Karl Marx wrote romantic poems and titled his books thematically. He gave the Book of Love and the Book of Songs to Jenny von Westphalen. Obviously, she loved it. Perhaps History owes a debt to these love poems that inspired the educated woman to renounce her studies and become a housewife? Obviously, History owes its wives nothing. But on November 10th of 1837, Karl Marx announced to his father that he’d abandoned poetry. No more lyric, Karl said, no more of this “shattering” activity which he had pursued rather vigilantly for the previous five years. Surprising: Marx's condemnation of Paul Proudhon's “poetic images” as unserious fluff-balls that elide the logic of social utility. Unsurprising: to note how the son grows to resemble the father in his puritanical seriousness and practicality.

/ hatred of poetry no. 63

“What joins me to B. is the impossible, like a void in front of her and me, instead of a secure life together. The lack of a way out, the difficulties recurring in any case, this threat of death between us like Isolde's sword, the desire that goads us to go further than the heart can bear, the need to suffer from an endless laceration, the suspicion even—on B.'s part—that all this will still only lead, haphazardly, to wretchedness, will fall into filth and spinelessness: all this makes every hour a mixture of panic, expectation, audacity, anguish (more rarely, exasperating sensuality), which only action can resolve (but action ...).” Thus reads a paragraph from George Bataille’s The Impossible, a hybrid work written as he filled the notebook that would later be published as Guilty. In 1942, Bataille was writing and reading poetry, including Arthur Rimbaud's A Season in Hell, William Blake's "Proverbs of Hell, Emily Bronte's poetry, and Lautréamont’s Maldoror and Poetic.

/ hatred of poetry no. 2

“Mystic hagiographies are writings that challenge the divide between immanence and transcendence and that often include poetry or otherwise heightened poetic language alongside theological reflections.”

/ hatred of poetry no. 19

According to François-René de Chateaubriand’s Memoirs From Beyond the Grace: “Frederick the Great, when he ascended the throne, had an intrigue with an Italian dancer, La Barbarina—the only woman he ever went near: he was satisfied to play the flute on his wedding night, beneath the window of Princess Elisabeth of Brunswick. Indeed, Frederick had a taste for music and a mania for poetry. The intrigues and epigrams of the two poets, Frederick and Voltaire, disturbed Madame de Pompadour, the Abbé de Bernis, and Louis XV. The Margravine of Bayreuth played a part in all this, as did love such as a poet might feel. Literary gatherings at the king's house, with the dogs on the unclean armchairs; then concerts in front of statues of Antinous; then enormous banquets; then heaps of philosophy; then freedom of the press and strokes of the cane; then a lobster or an eel pie, which put an end to the days of a great old man, who wanted to live: such are the things that private society took up during those days of letters and battles.—” Poetry and pet lobsters: the dream of any self-respecting dandy, as well as the scourge of an respectable bourgeois professional.

/ hatred of poetry no. 2025

“In this case it would be necessary—and also possible, easy— for us to make this wound a festival, a strength of the sickness. The poetry that loses the most blood would be the strongest. The saddest dawn? Announcing the joy of the day. Poetry would be the sign announcing the greatest inner lacerations. The human musculature would only be entirely at stake; it would only attain its highest degree of strength and the perfect motion of decision— that which the being is [incomplete sentence]”

/ hatred of poetry no. 117

"And so I dismiss these matters and accepting the customary belief about them . . .I investigate not these things, but myself, to know whether I am a monster more complicated and more furious than Typhon or a gentler and simpler creature, to whom a divine and quiet lot is given by nature," Socrates said in Plato's Phaedra. Like Socrates, sometimes the poet must compare herself to Typhon and ask what sort of monster am I? Certainly I am more clever than Hesiod's serpent version, who gives himself away with his hundred serpent tail legs and hundred serpent heads. But I am also dumber than Typhon, who can imitate any sound and speak and countless voices including the language of the gods with his many mouths. Typhon's goal was to replace Zeus as the most supreme being in the cosmos. The battle between Typhon and Zeus ended badly for Typhon; Zeus used his thunderbolts and threw him into Mount Etna. But Typhon had the last word by inscribing his rage in the sky. Whenever Typhon thinks long and hard about what Zeus did to him, whenever that fury is fondled and recollected to the point of obsession, Mount Etna rumbles and its volcano spews lava into the sky. Zeus strikes those of us on the earth with a thunderbolt, while Typhon strikes at Zeus from inside the earth with lava and smoke. Both are monstrous. What will my desire to unseat the powers that be cost me? What harm will I revisit upon other humans in fighting this battle? This is what the volcanic mind must ask. But this is also what the hero cannot consider when battling the monster. And maybe this is one indirect way of answering your question about why the poet cannot be a hero.

/ responses to hatred[s] of poetry

Toti O’Brien’s interview with the extraordinary Dimitris Lyacos

May Ray, Adrienne Fidelin and Nusch Eluard (1938)

The hatred of poetry

The art of hating

The hatred

The gender of sound

The unfortunate fate of childhood dolls

The work of fire

The plastic semiotic

The behavior of mirrors on easter island

The phaedra

Eva Hesse, Untitled (1962)

Michael Hamburger, “No Hatred and No Flag”

The conditional

The hairpin curve

The custom of wearing clothes

The absent meow

The scythians

The well-ventilated conscience

The grocer’s cat

The autobiography of death

The privilege button

The art of inhumation

Brisees by Michel Leiris

The illusion of historic time

The palimpsest of the human brain

J. M. W. Turner, Death on Pale Horse (maybe 1825-1830)

Benjamin Fondane’s Philoctetes

The collective afterlife of things

The surreality of community

The postscriptum

Rosa Boshier González’s “Philip Guston Now”

Material in Seurat’s nude study of an old man: “powdered vine charcoal and charcoal with stumping and lifting, on laid paper”

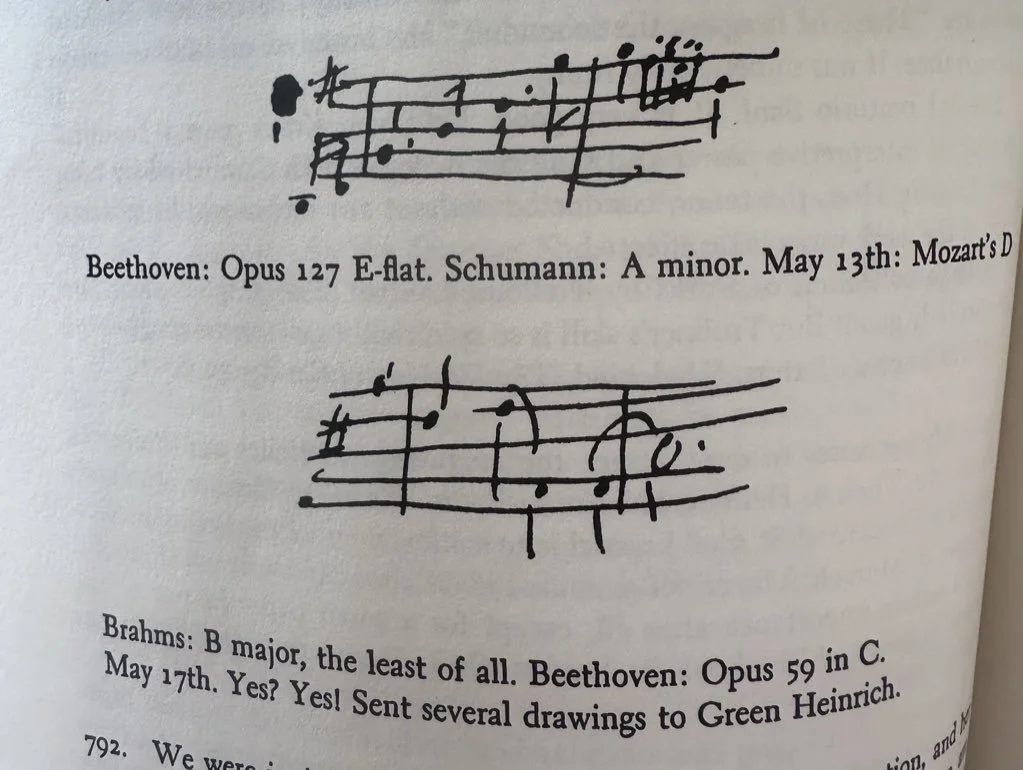

Paul Klee speaking B.

*

François-René de Chateaubriand, Memoirs from Beyond the Grave: 1768-1800 (NYRB Classics) tr. by Alex Andriesse

Georges Bataille, The Impossible (City Lights Books) tr. by Robert Hurley

Georges Bataille, Guilty (Lapis Press) tr. by Bruce Boone

Georges Bataille, Guilty (State University of New York) tr. by Stuart Kendall

Harold Brodkey, Sea Battles on Dry Land (Metropolitan Books)

Reiner Stach, Is That Kafka? (New Directions Press)