The world is everything that is the case.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein’s first statement inTractatus

What we cannot speak of we must pass over in silence.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein’s final proposition inTractatus

What can be written down is mere foolishness. Only the ineffable is of any importance.

– Paul Valery, Mon Faust (a play)

1

In 1940, Walter Abish and his parents fled Austria and the Nazis. A few years later, they had to flee Italy. When the Germans took the Ardennes, they fled France. Later they fled China when the Maoists gained control. Finally— if such words can exist in our world — Abish wound up in the US metropolitan of New York City, the place that became his home.

“I lie and I am lied to, but the result of my lie is mental leaps, memory, knowledge,” Abish wrote or remarked — somewhere.

The world is everything that is the case.

But no where is what it seems. Abish’s novels and essays are constructed from texts cobbled together from the memoirs, correspondence, experience, and lives of others. He doesn’t cite his sources or name the humans whose lives he collages. Nor does he guise his own autobiographical presence in what he tells or re-collects.

Across his writing, the use of a collective first-person pulls us back from the autonomous being of the neoliberal subject. Oddly, nothing feels more contemporary to this moment than Abish’s novel, How German Is It (1980) . . .

2

As sovereigns would have it, the child lives under the sign of the name given by the father.

Walter Abish’s protagonist, Ulrich Hargenau, lives in the shadow of his father’s execution by the Nazis for his involvement in the 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler. The father was part of a terrorist conspiracy to invalidate the rule of the sovereign. Worst of all, the planned assassination symbolized a rejection of the Furher principle from within the ethnocentric shelter of what was constructed as the “German family.” There is no foreign Other — no “alien ideology” like Bolshevism, no filthy blood of drawn from Slav minorities, no “contamination” of Jewish or Roma blood— involved in this plot. Which is German.

But what is German about the terrorist.

And what is German about the son who returns to the region of Württemberg, where he was born, in order to find the father.

What we cannot speak of we must pass over in silence.

What Hargenau seeks is history, a narrative to structure the frayed threads of his life— the marriage to a woman named Paula who nevertheless remained a mystery, his pseudo-participation in the leftist radical Einzieh Group and the resulting arrests of his friends, the role he played in their judicial trial and subsequent conviction, the novel he didn’t write, the novel he seeks to finish, the lived and unlived lives that haunt his experience.

What part of repetition do we need to remember the lullaby’s texture.

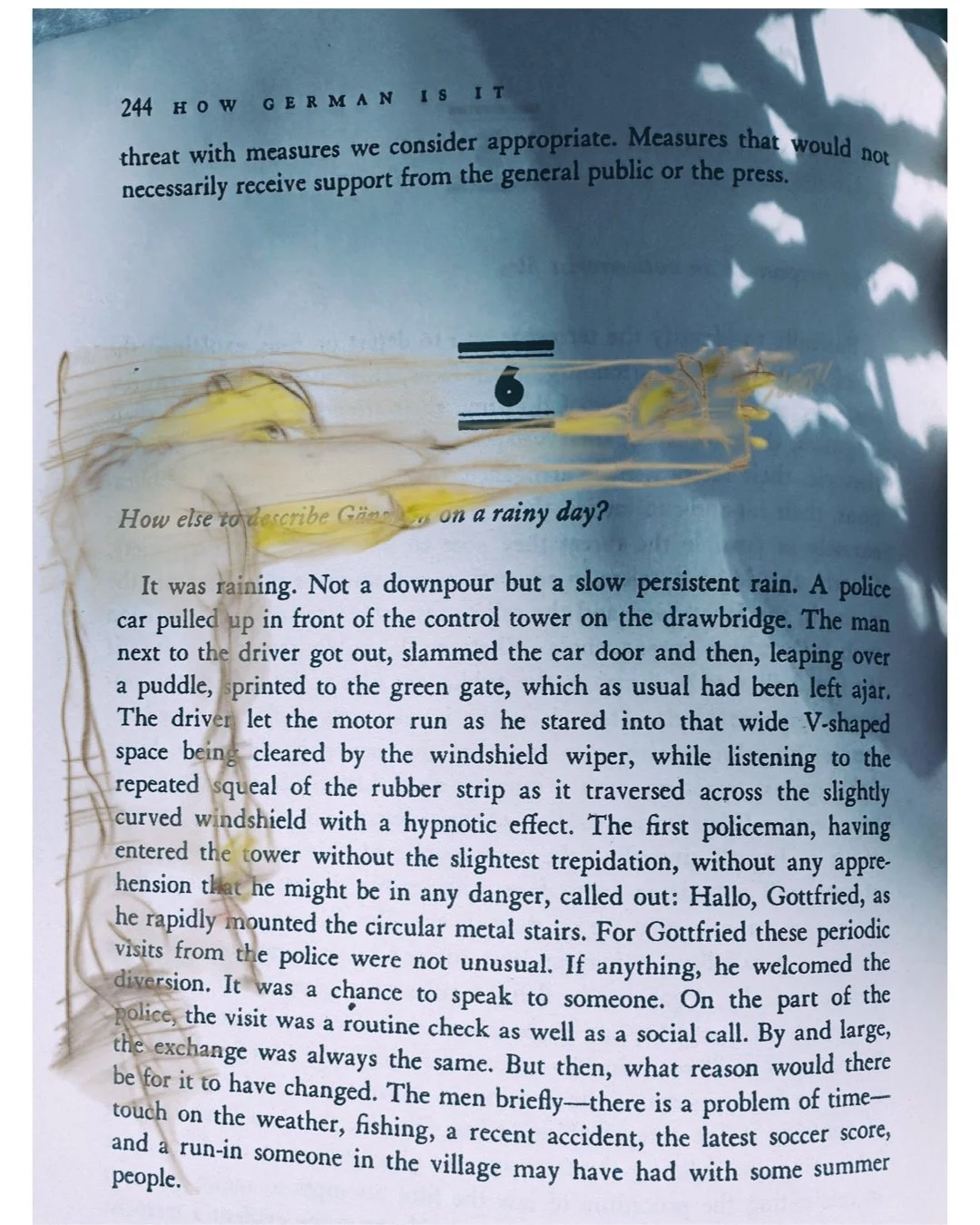

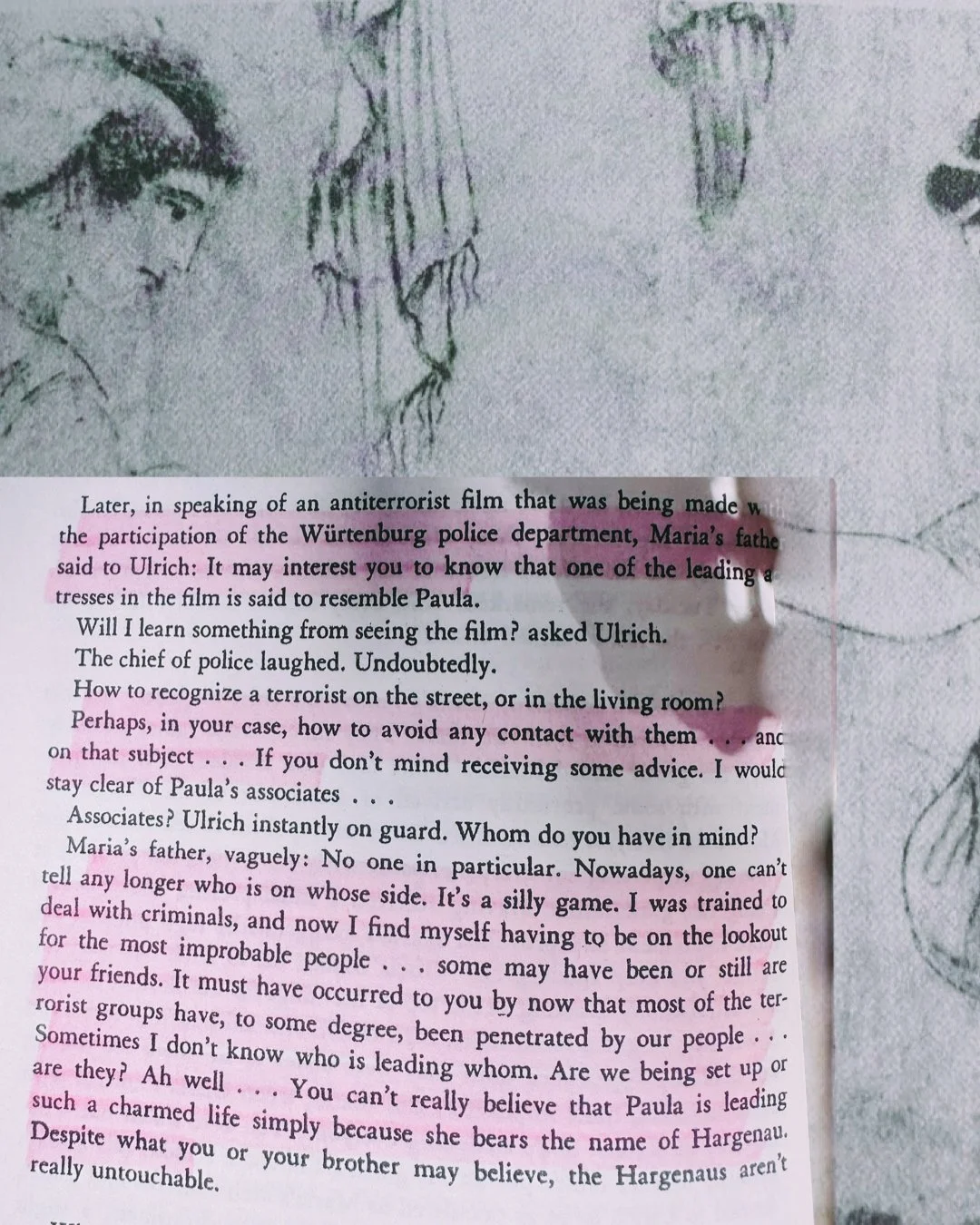

“The purpose of an antiterrorist film” (excerpted below) resembles the language of contemporary global fascism, particularly in the Trump administration’s prosecution of student protesting their government’s support for Israel’s ongoing genocide of Palestinians.

But no matter how great these flaws, the need for the film is self-evident.

Who is the terrorist in the history empire tells.

“At the subconscious level nothing is accidental,” said Luis Buñuel in That Obscure Object of Desire, a film that made use of the flashback form and, coincidentally, was cited by Abish as a personal favorite.

The book ends in an abrupt flurry of ellipses structured to represent the associative possibilities of stream-of-consciousness. Sitting in an office, Ulrich recounts his childhood to a psychoanalyst. He was born in Württemberg in 1945, the year after his father’s execution. At age 7 or 8, Ulrich found this gap, but never discussed it with his (mother who later remarried a former Wehrmacht officer with a high status at a bank).

“I am a bastard,” Ulrich says, “an appropriate role for a writer,” or any man who doesn’t want to know who his father might have been, or what his father did during the war.

What can be written down is mere foolishness. Only the ineffable is of any importance.

Ulrich exhibits a subconscious needs to replay his father. By joining the Einzieh Group, he satisfies the urge to identify with the conspirator in his father. Deploying flashback and dialogue to maintain a discontinuous time, Abish renders a time whose movement forward is arrested by the absence of meaning. The characters relate, openly and covertly, to the national history. Neighbors cut shrubbery and hum over the interior monologues; everyday actions drown the proximity of inherited guilt and salvation complexes in the postwar generation.

On the surface of things, Ulrich believes that he joins the Einzieh Group for a love of a woman whose “real name” he did not know. Her name hid her past and buried her father twicefold: once in the ash of public buildings she bombed and again in the effort to trace her lineage back to a father whose sin may have been unforgivable.

“What she couldn’t have known is that the name I hear is not my real name either,” Ulrich tells the analyst.

Ulrich’s search for his father in Württemberg, where he goes to work on his novel, is also a search for his own heritage, an effort to find his inheritance, a question about what it means to be German after the Holocaust. Each time Ulrich pronounces his own name, Germans recognize him as his father’s son. In these moments, he says, “I am practicing a kind of deceit.”

3

Heidegger appears as the father of German metaphysics, the man who lives in the forest of uncontaminated purity, the gnome whose language refuses to be penetrated or altered by the foreign. A town built on top of a mass grave is named after him. A ‘terrorist’ may have studied under him, as did the protagonist. All of Abish’s character have a connection to Heidegger, however large or pithy, if only as residents of a town developed and built atop the crimes of the past to better honor the future.

4

A few excerpted passages from an essay by Walter Abish titled “What Else”:

79

I keep beginning again. I keep taking a fresh notebook. And each time I hope it will lead to something, that it will be a constructive experiment, that I shall open some door. It never happens. I stop before I get to a door, any door. The same invisible obstacle that stops me. I ought at least to try and keep the same notebook, to get to the last page. That would mean that I have said almost everything.

97

From the past, it is my childhood which fascinates me most; these images alone, upon inspection, fail to make me regret the time which has vanished. For it is not the irreversible I discover in childhood, it is the irreducible: everything which is still in me, by fits and starts; in the child I read quite openly the dark underside of myself-boredom, vulnerability, disposition to despair (in the plural, fortunately), inward excitement, cut off (unfortunately) from all expression. Contemporaries: I was beginning to walk, Proust was still alive, and finishing A la Recherche du Temps Perdu.

168

Her apartment: for reasons that are no longer clear to me, a few weeks after that first evening in her apartment, we moved the convertible couch from the north wall of the living room to the west wall. After we parted, but before we were married, the furniture was moved once again, as if to erase my former presence. I can understand the movement of the furniture as well as and as passionately as I understand Schubert's sonatas. The aquarium with its dozen guppies was by now long gone. After we were married but living apart, she once again moved the couch. I often wonder if I avoided sleeping with her after we were married for the sake of the text-to-be? I believe she, had not read The Sun Also Rises but her parting words seemed straight out of that all too familiar exchange in the novel. Am I reading into her parting gift, Malraux's The Voices of Silence, a meaning that wasn't there? Why write?

4I

July 31. One can imagine a face for the void. Then it strikes us how much the void resembles us. Is it myself I am staring at? The dark is checked by the dark, as a hand by a stranger's hand.

I3

Jean Jacques Rousseau confesses himself. It is less a need than an idea.

46

What tense would you choose to live in?

I want to live in the imperative of the future passive participle-in the “what ought to be.”

I like to breathe that way. That's what I like. It suggests a kind of mounted, bandit-like equestrian honor...

An epigraph from the second part of Walter Abish’s novel, Eclipse Fever.

*

Arvo Pärt, Silentium

Broken Social Scene, “Hug of Thunder” (2017)

Dennis Cooper on Abish’s How German Is It

Jacek Malczewski, Zesłanie Studentów, or “Student’s Exile” (1891). Black and white reproduction.

Leoš Janáček, Idyll For String Orchestra, V. Adagio, performed by Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra

Walter Abish, How German Is It (New Directions Press, 1980)

Walter Abish, Eclipse Fever (Nonpareil Books, 1993)

Walter Abish, “What Else”