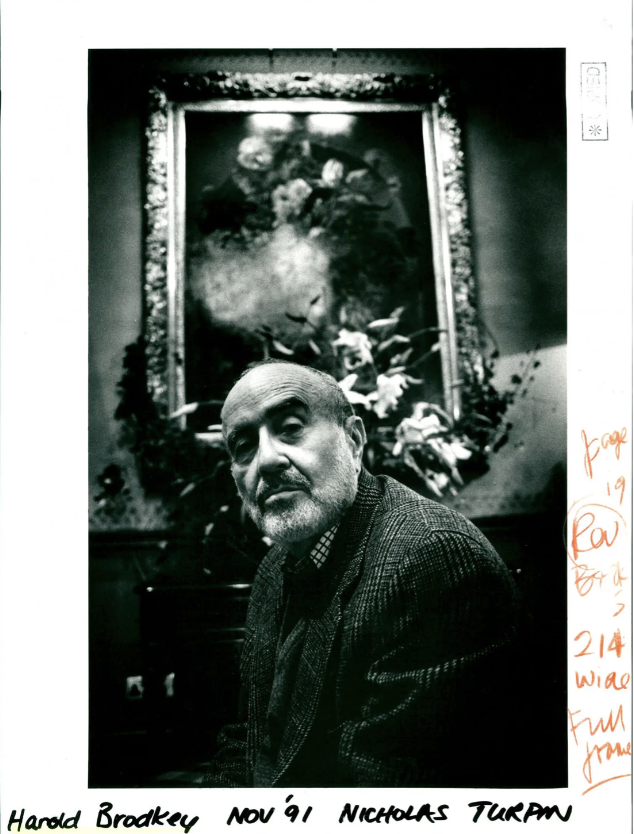

Harold Brodkey (Source: Alto de la Luna)

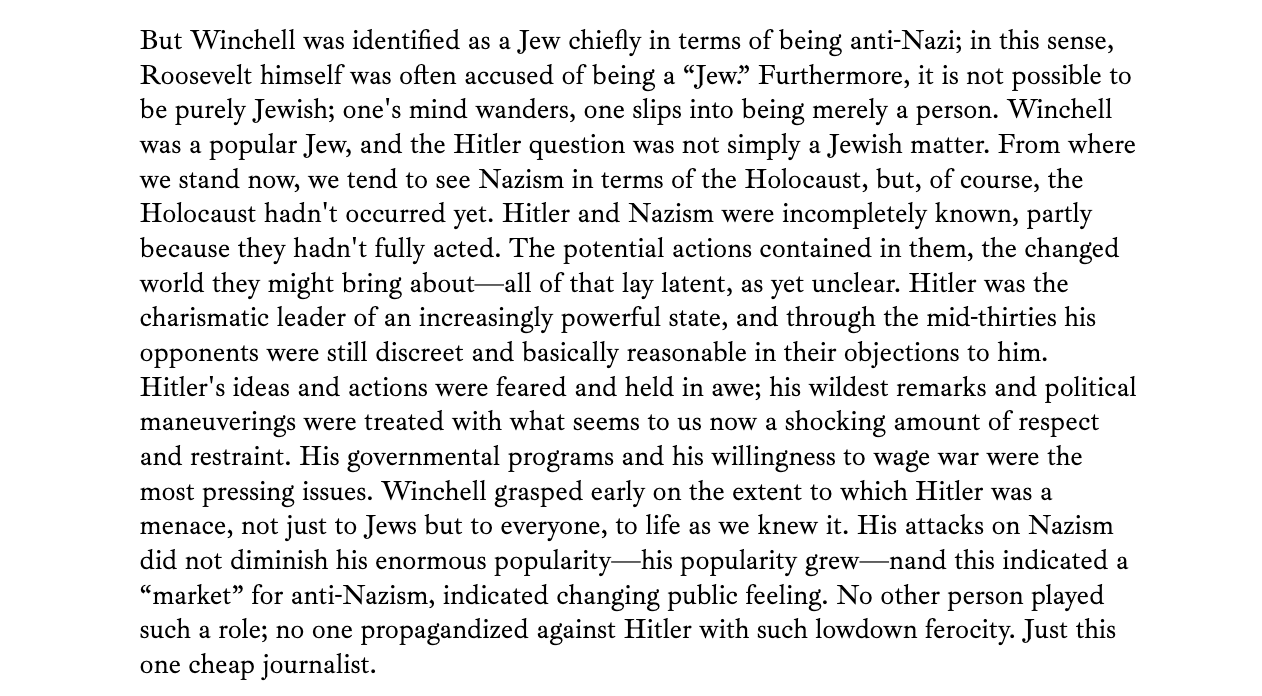

Take “order” as the arrangement of sensible things that permits repetition, ritual, and recognition. Then go for a walk with Radu, head tingling with recent readings. Enter Harold Brodkey’s 1995 essay, “The Last Word on Walter Winchell” — and my urge to excerpt abundantly, if only to imagine talking to other humans about it.

Brodkey begins in his feelings, as usual, regardless of what you might prefer. For Brodkey writes in the world that is Brodkey, for the page of his own reckonings. Love him or hate him, at least he doesn’t prevaricate a feigned neutrality or emotional disconnection.

Biographers claimed that Winchell invented the modern gossip column, perhaps as a way of defending their interest in him, but Brodkey disagrees. Journalism as gossip predates Winchell “by at least half a century.” Winchell merely revived a “dying form” and “made it commercially viable” among a mass audience.

It’s no shiner to say Winchell looked fantastic in the bootstraps department. Raised in Manhattan, he left school after the sixth grade. Although Brodkey was raised in a smaller town, he and Winchell were both socialized by a similar American conception of masculinity and nuclear family. Respectability and new money had altered the social terrain. “The rich, the people who mattered, were (with some exceptions) arrivistes, newcomers to power since the Civil War,” wrote Brodkey, emphasizing their inclinations to be “genteel.” The performance and display of “gentility was a constant issue,” and the fiction of the time attested to “this hypocrisy.” Media entered the market fray. “Newspapers were power and blackmail: they printed scandal, often unsubstantiated.”

Perhaps the myth of the American gentleman has always been nostalgic. “America was not gentlemanly except as a quality of longing,” wrote Brodkey, before segueing into a description of early alienation that confronted him when he moved from a small town into a larger city:

Angling into this sociology of small-town abandonment, Brodkey concentrates on the sense of scale; how considerations of scale shaped Winchell’s persona, or provided the terrain for his reactions and self-makings. “The thing about going back in history is that it is difficult to keep your sense of scale”:

Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Winchell “kept this sense of a party through much of his working life” — and the sense of party may have influenced his style, or what Brodkey calls his “swiftness and nastiness and outspokenness.” Style, here, is prophetic and smug in its clapbacks and near-aphorisms. It draws on common language and sounds personal, easygoing, honest as a televangelist. This isn’t why Brodkey traces Winchell’s style back to “Bible, with its air of truth.” What he borrows from the Bible is a certain pithiness: “Winchell's idea of a story was Jezebel in five lines.” He never used “schooled rhetoric” and “his riffs depended on rhythm, brevity, and mocking parody, in ways reminiscent of song lyrics and vaudeville.”

Walter Winchell.

In the absence of authoritative institutions, Winchell’s instincts presumed the market would drive values. Decades later, Pop would be disavowable king around which American culture could be constructed. To quote Brodkey, “Not simply because his work was entertainment but because in a country with so many ethnic divisions and a maddening variety of manners of speech, show-biz vernacular was the only common language.” If Winchell was anything, he was “show biz, was a placeless American, someone who could not be kept down on the farm after he'd seen Paree.” He stayed conversant with trends and presented himself as an afficianado of immediacy and instants.

Perhaps this caused a sense of giddiness in his respectability-battered audience?

“Winchell's constructed persona was based on his being truant, on his autonomy, and it granted us, the citizen audience, our autonomy,” said Brodkey. The man didn’t bother with ancestors or history or “dead men's and women's greatness” or even “memories of greatness.” Instead, Winchell “was absolutely topical. Now. Our lives.” The popularity of his work depended on how he played to “his two lifelong interests . . . sexual reality and conspiracies.”

Content aside, Winchell’s performance had polish. He knew his audience. He met them in their loneliness. “His métier was the folksy deconstruction of officaldom and of lies about class differences.” He finessed headlines and didn’t bother with telling “the ‘truth’ except in a sportive or arch manner, and even then he didn't do it because he was truthful by nature.” He kept his eyes focused on the lies of others. He took so many notes on those lies and contradictions that J. Edgar Hoover assigned agents to listen to Winchell and reap details.

As a medium, radio foregrounded voice and vocalization. Winchell’s voice ranged an “octave higher than usual” when he was on the air. His “verbal style” celebrated “childishness” and the patina of innocence required for shock. According to his biographer, “Winchell liked to broadcast with his pants undone.” According to Winchell, radio “added to his already terrible nervousness, his stage fright, and helped increase the urgency and drama of his voice on his broadcasts.”

Beginning in 1933, Winchell dedicated his broadcasts to opposing the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany. He wrote frequently about the activities of pro-Nazi groups and funneled this information to a very-grateful Herbert Hoover at the FBI. By 1934, Hoover had even assigned FBI agents as a personal protection force for Winchell, since — in Hoover’s words — Winchell “has been very active in the anti-Nazi movement and feels there may be some efforts to cause him harm or embarrassment.” Protection rackets proliferated, and Winchell received protection from The Mob for several years (though Brodkey doesn’t mention what this cost him).

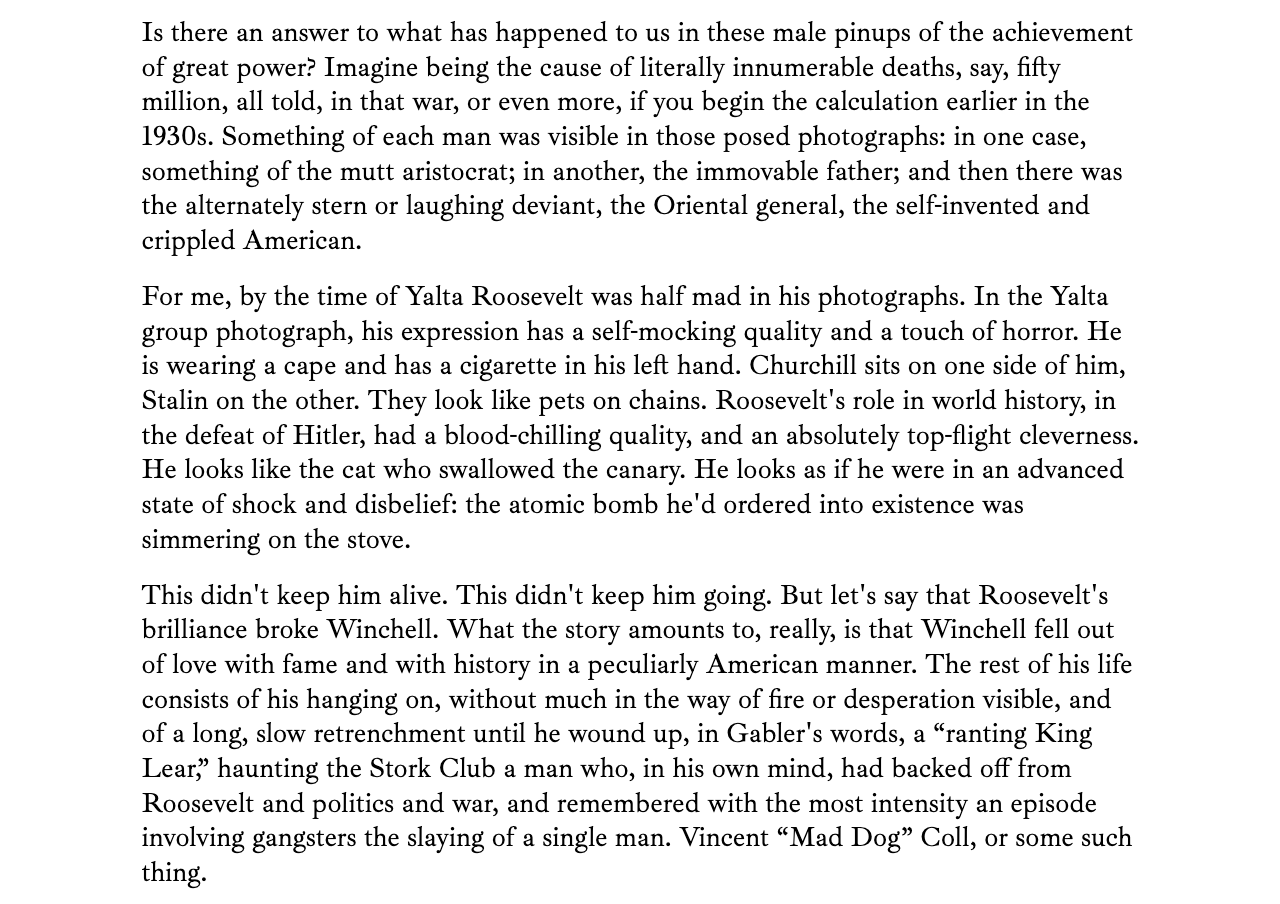

The next passage deserves quotation in full, if not for its grist with fragile masculinity and fascism, a topic that Brodkey never tired of challenging in his fiction:

Brodkey also takes issue with the biographer’s depiction of Winchell’s relationship to Roosevelt (i.e. Winchell started stumping for Roosevelt’s policies because they shared a similar sense of judgement, and not because he was fawning for significance) as well as his relationship Judaism (i.e. Winchell wasn’t deeply indebted to his ethnicity or religious belief for a sense of identity). With a note that he might be projecting a bit, I give you Brodkey’s words on this:

In this directed, ceaseless opposition, Winchell altered the stakes of activist journalism. Policies were not distinct from their consequences on the speaker.

The pleasure of Brodkey’s hard-nosed sentimentalism surges through his irreverent description of the self-styled Great Men — Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, etc.

Speaking of gender, Brodkey loved pontificating from his androgyny platform. No literati did more to elevate the humbug, totally- average androgyne than Brodkey. Take the way he marveled at the newness of Marlon Brando's “questionable morality and the questionable morality of his art, its graffiti quality, its shitting-on-you wildness… “ and described Brando's eyes as “clever, androgynous, hauntingly threatening eyes, somehow also soft and weak, satyr / American-storm-trooper eyes (though they are less famous than his profile).” This is only to provide context for Brodkey’s survey of the “huge, androgynous vanity” of the Yalta bros . . .*

After the war ended and the troops came home, American triumphalism leaned into the profits made by weapons manufacturers. It was a rich man’s war, which is simply to acknowledge that modern warfare tends to expand the ruling classes to include men who get rich from war. In a sidelong manner, Brodkey suggests that Americanism didn’t properly exist until the War created it. All that nostalgia for the 1950’s among MAGA-heads gives credence to longing for a sense of community that was manufactured by media and the culture industry.

In Brodkey’s words:

And then, “we” — by which Brodkey means the Americans — “tried to go back in time.”

Women got shipped back into kitchens—”and into waist cinchers” (which are back, by the way). Tradwifes were more than fifty years away, but the seeds for the domestification of wifey had been planted and women’s magazines would sow the profits. Lawnmowers entered the national lexicon and “the country made suburban noises.”

Behind June Cleaver’s smile brewed resentment. Brodkey traces the rise of xenophobia and McCarthyism to our war-generated obsession with personal safety and greed. The “Roosevelt legacy was so complex and generated so much power and aroused so much ego that moral cowardice and personal safety and corruption and self-doubt and unlimited greed became national characteristics and national virtues.” No one knew how to behave in the newly-minted context. Women clearly weren’t stupid but they acted dissatisfied. Pastors and churches began plotting the Culture Wars that would define the 1960’s (and later make Evangelicals the most faithful voters and supporters of Trumpism). Social change scared the average Joe. “It felt as if this were a country consisting entirely of recent converts, and everyone went on tiptoe,” wrote Brodkey, noting that “McCarthyism came first,” and defining McCarthyism as “an attack on the upper-caste white Protestants that Roosevelt distrusted” and then on Hollywood folks and theatre people before finally becoming “a move toward a popular coup.”

Unsurprisingly to pesso-optimists like me, Winchell swiftly pledged his troth to McCarthy “and publicly attacked Truman and Stevenson, calling them ‘un-American’.”

Like any abstraction based in smug superiority, Americanism is whatever the corporations and politicians desire to emphasize safety against the internal enemy. Brodkey says Winchell later abandoned McCarthy, but I’m more intrigued by his claim that McCarthy spoke for the veterans:

Brodkey ends on a note of demystification (or perhaps remystifying the Everyman as American). “Winchell had a Job aspect and a Noah aspect and a bit of Lot's wife in him, too. He railed at fate, he fought it, and he won for a while and, of course, he lost in the end. And it broke him. It is practically everyone's story.”

As for safety, it always lacks an endgame. Pandering continues. A politician’s vow to offer safety to their constituents is also a promise to build more prisons, more bombs, more carceral spaces, and more violent deportations of underprivileged persons. Investors and the corporate leaders are listening. The “new social reality” shares much with the old social reality of American capitalism: the rich get richer.

*

Denis Donoghue, “Harold Brodkey: A Proustian Progress” (Vanity Fair, March 1985)

Harold Brodkey, “The Last Word on Walter Winchell” (1995)