7 /

Undisputable acumen is what Nathaniel Hawthorne noticed in his frenemy, Henry David Thoreau, whom he called “a genuine observer”; Thoreau, whom he saw as the “especial child” of Nature who “shows him secrets which few others are allowed to witness”; Thoreau, who remained “on intimate terms with the clouds” as the two men ate watermelon and muskmelon from Hawthorne’s garden; Thoreau, who had written a piece for The Dial containing “passages of cloudy and dreamy metaphysics, and also passages where his thoughts seem to measure and attune themselves into spontaneous verse, as they rightfully may, since there is real poetry in them.” Thoreau, whose words contained “a basis of good sense and of moral truth . . . which also is a reflection of his character.” Thoreau, whom Hawthorne found to be “a healthy and wholesome man to know,” like the granola cereal boxes lining the shelves of the 20th century’s market for good health.

8 /

Carnivorous fortunes, delicately referred to here as “bull market.” Obviously, Hans Richter continued to mourn his unfinished cinepoem, Minotaur, as the heart of the art mourns the unfinished and the unwritten.

“This isn’t what I imagined,” said the active child.

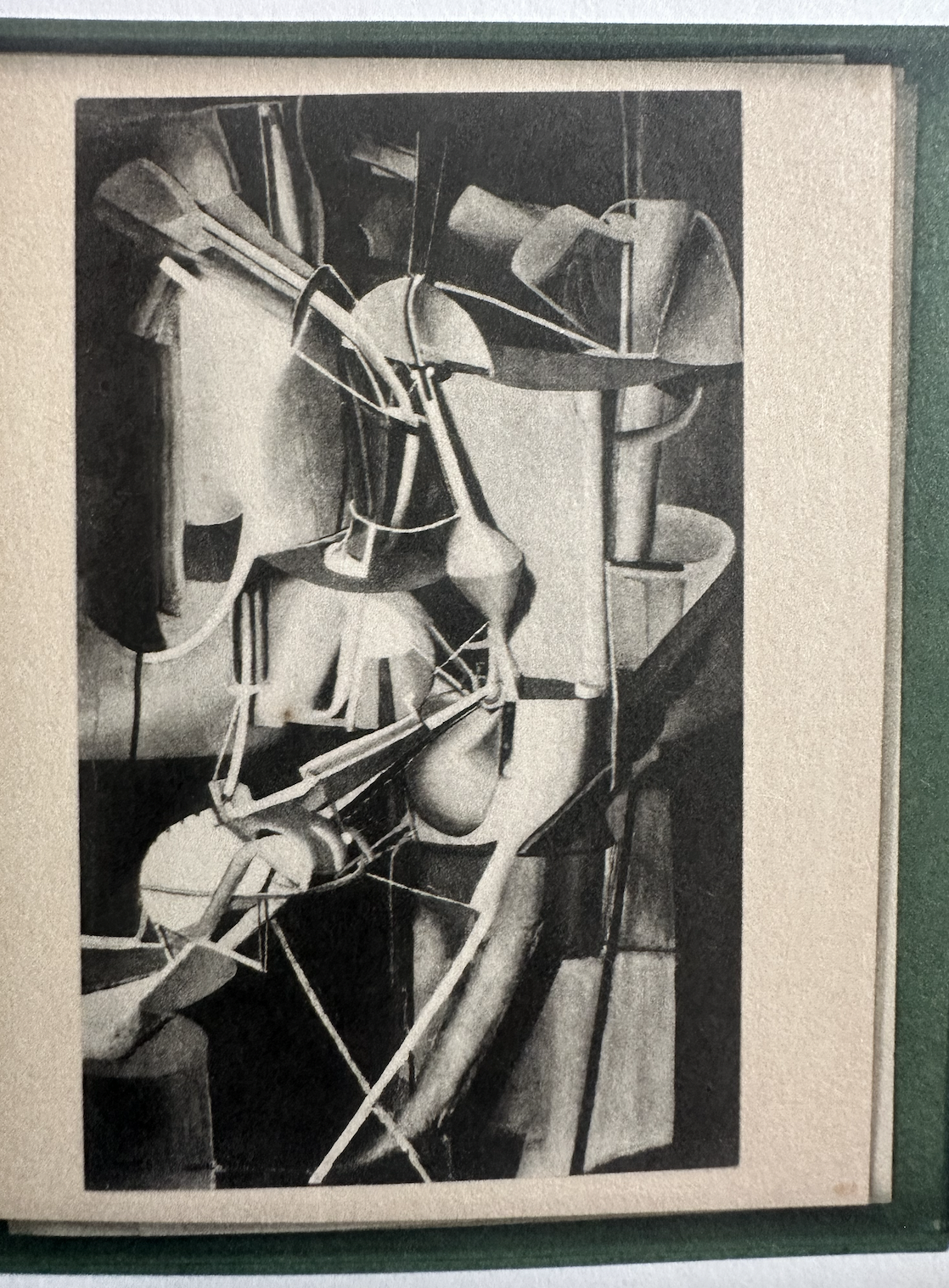

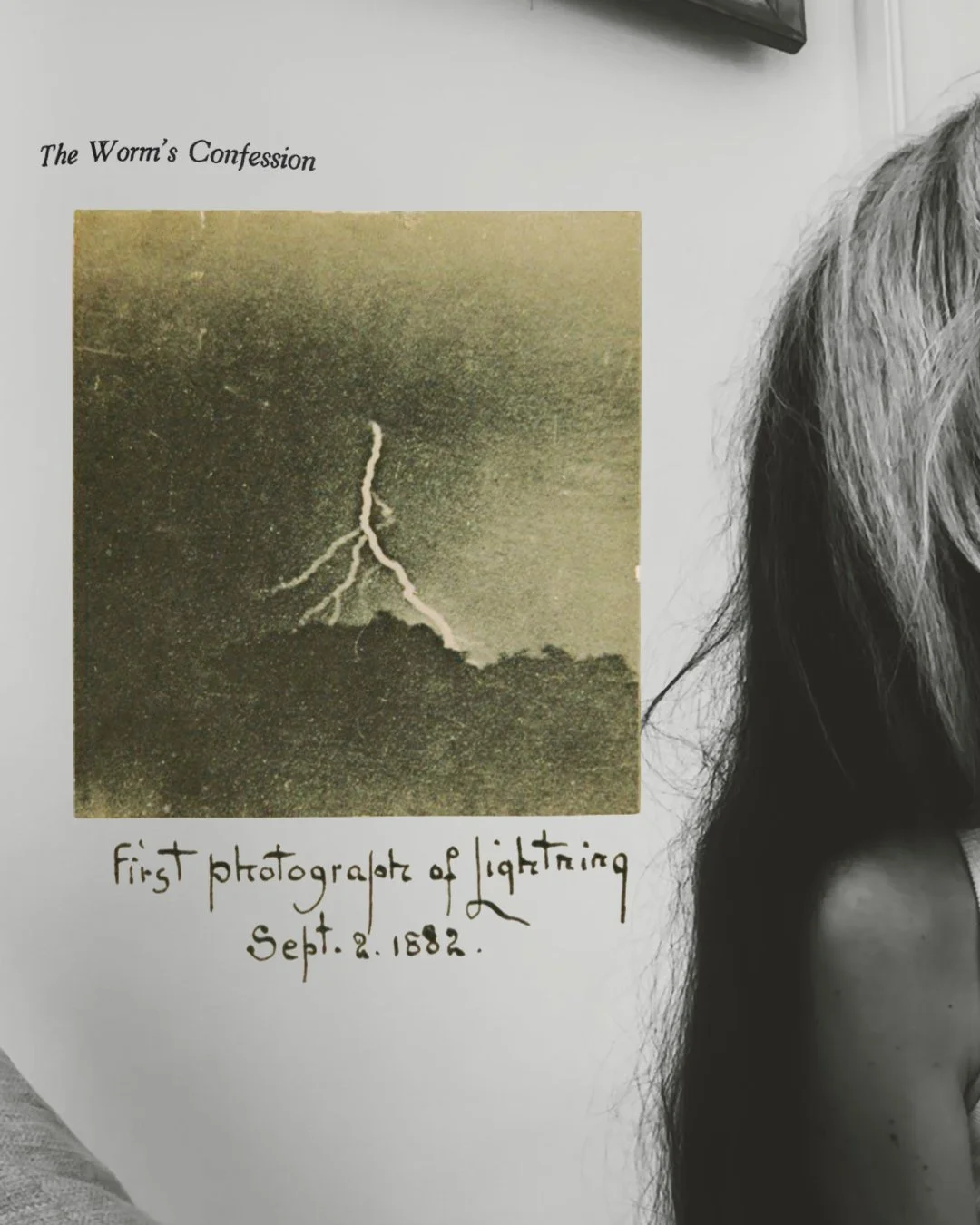

At some point near or around the year 1935, Mary Sully created a portrait that was closer to an evocation than a realism-based representation of celebrity scientist Charles Steinmetz, an electrical engineer who discovered the Steinmetz Curve of electric alternating currents. In Sully’s panel, blue energy waves alternate with arrow-like cross currents which appear and concentrate in the center panel. Loosely resembling a circuit diagram, red diamonds connect with the green ovals, and the bottom panel links the alternating currents with the cosmologies indicated in Dakota and Lakota patterns.

“This isn’t what I had in mind,” the child remembers saying.

What was the heart doing on March 17, 1922, when Rainer Maria Rilke sent a letter to Countess Margot Sizzo-Noris-Coury, announcing the completion of his Duino Elegies, and connecting the lyrics, themselves, to the destruction of Duino Castle during World War I? Where was the heart when Rilke told Countess Sizzo that the elegies felt true— “the more so” — shaped by their form, since the war had destroyed the castle that had inspired them. What carnage of the heart led Rilke, in this same letter, to employ the word “constellation” in a manner that might have reached Walter Benjamin, whose first love was reserved for the idealistic poet friend that died by suicide?

9 /

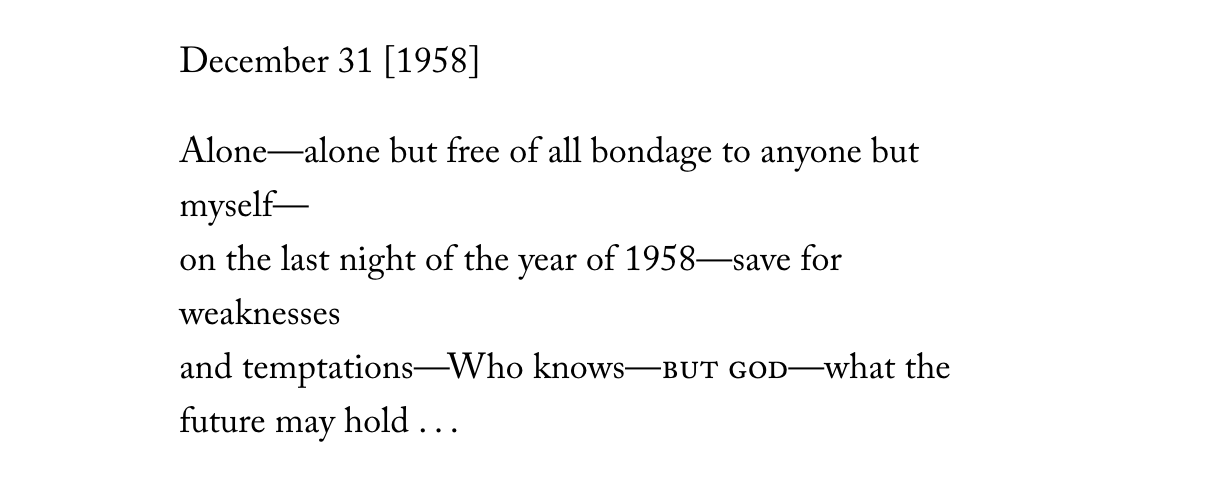

And (of course) other irrational factors, including the desire to accept the selves we performed in the past— which may be what sat like a toad on Fred Davis’ forehead when he wrote: “The proclivity to cultivate appreciative attitudes toward former selves is closely related to nostalgia’s earlier-noted tendency to eliminate from memory or, at minimum, severely to mute the unpleasant, the unhappy, the abrasive, and, most of all, those lurking shadows of former selves about which we feel shame, guilt, or humiliation.”

9 /

Deadly smoke thick over the icecaps.

Awful — a word that could have rested in its sublime etymological origins, where “awe-” attaches itself to “full” and looks down from the romantic cliff on the ineffable below. But the perspective has changed. Awful, the look on my daughter’s face when she dreams of her grandmother wandering through the icecaps of Antartica. In the nightmare, the glaciers retain that excruciating brightness, the blue-white of so much light encountering itself in millennia of ice. “Dream,” I tell my daughter. The nightmares know water. We move like a bad scene, shot in the dark.

10 /

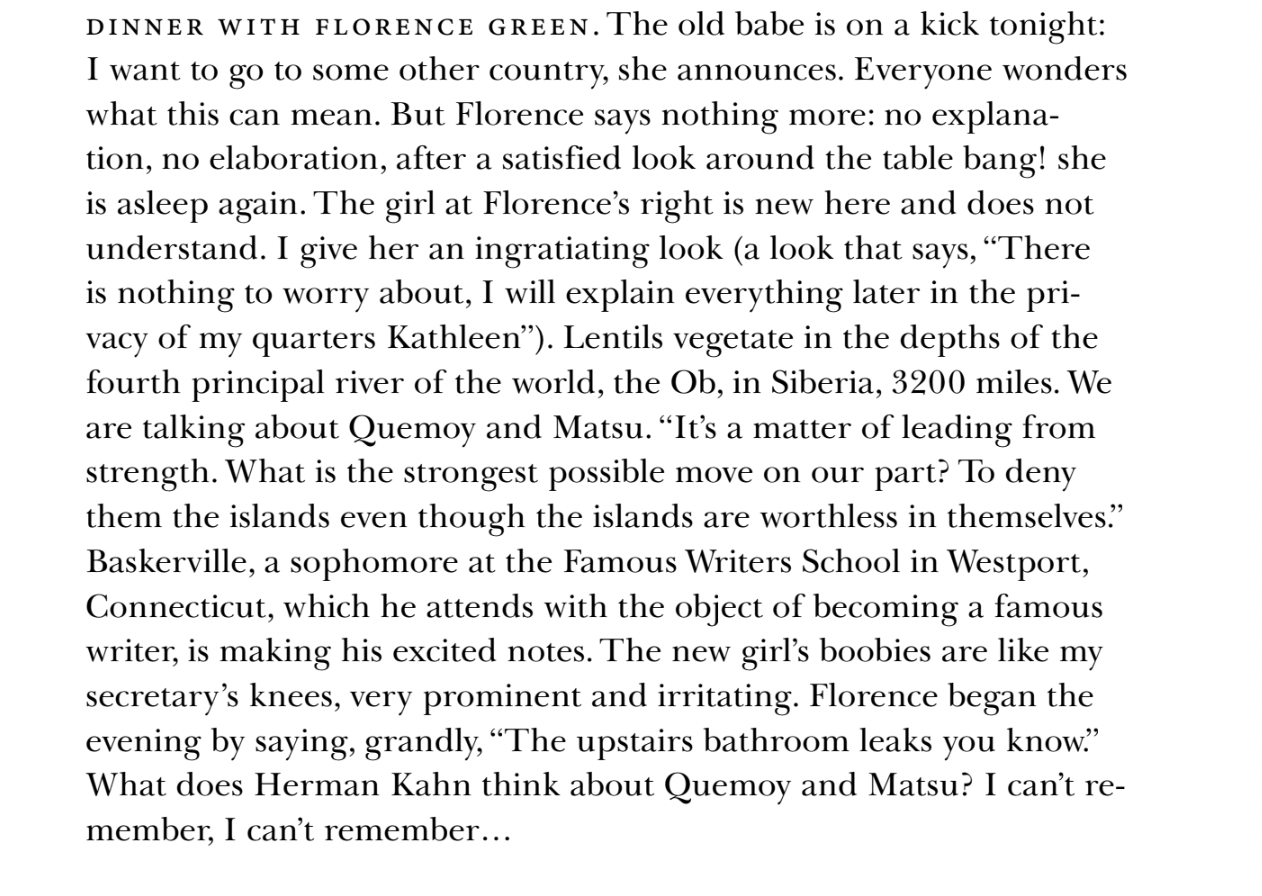

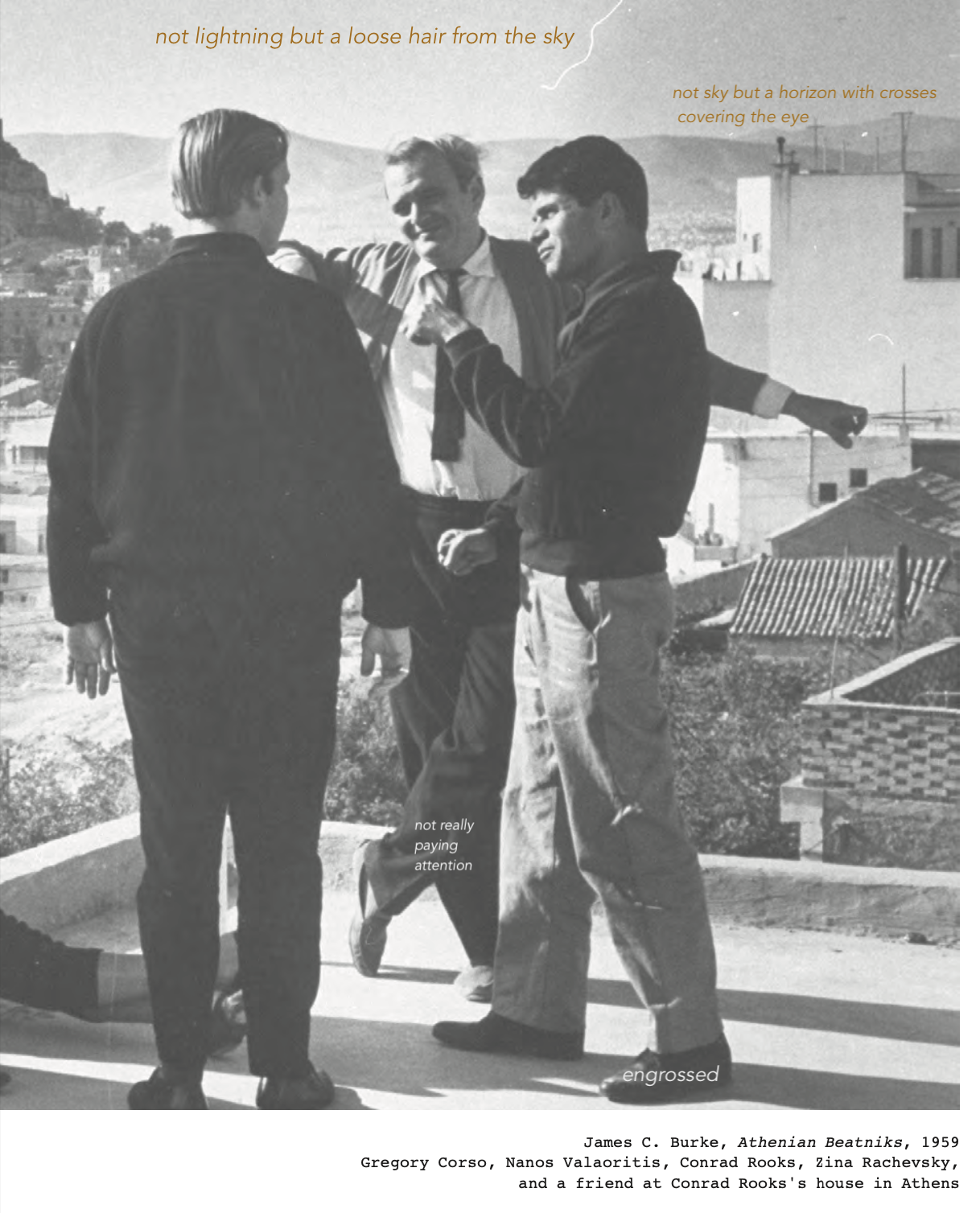

Our man in Saigon, Lima, Tokyo etc.

The poet ignores our man and keeps her eye on the bottle.

She thinks of Mandelstam and all those Egypts — all those possibilities of place and homeland tucked into the correspondence of the writers she can’t forget.

11 /

Etc etc., or the way the umbrella moves through John McGahern’s short fiction, “My Love, My Umbrella”

It was the rain, the constant weather of this city, made my love inseparable from the umbrella, a black umbrella, white stitching on the seams of the imitation leather over the handle, the metal point bent where it was caught in Mooney’s grating as we raced for the last bus out of Abbey Street.

[...]

We went to cinemas or sat in pubs, it was the course of our love, and as it always rained we made love under the umbrella beneath the same trees in the same way. They say the continuance of sexuality is due to the penis having no memory, and mine each evening spilt its seed into the mud and decomposing leaves as if it was always for the first time.

[..]

‘Would you think we should ever get married?’ ‘Kiss me.’ She leaned across the steel between us. ‘Do you think we should?’ I repeated. ‘What would it mean to you?’ she asked.

What I had were longings or fears rather than any meanings.

Umbrellas protect us from getting wet. The umbrella is also slang for condoms, I think?

Perhaps protection is the “constant weather” of failed love. I mean, “imitation leather” never handles the dead animal; it never risks the unprotected part of it.

Looking forward to thinking aloud with other writers this week, while also thinking on paper, in notebooks, on screens, about filiative schemes, inaugurations, synecdoches, constellations, decomposing leaves — and the Kierkegaardian repetition in the “always for the first time.”

*

Active Child, “Diamond Heart”

Chelsea Wolfe and Mark Lanegan, “Flatlands”

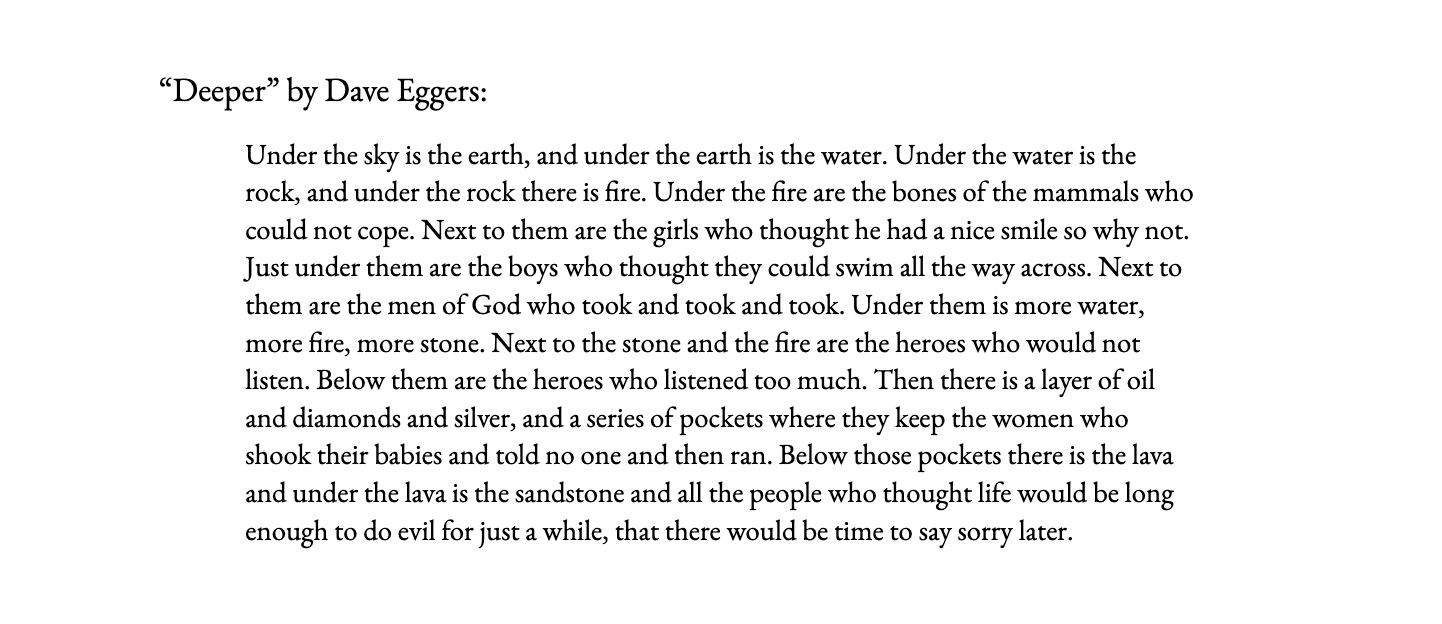

Fred Davis, Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia. New York: Free Press, 1979.

Henry David Thoreau, “1842”, The Thoreau Log.

John McGahern, “My Love, My Umbrella”

Junior Wells, “In the Wee Hours”

Lorenzo Thomas, “Inauguration”

Man Ray, Gift, 1921.

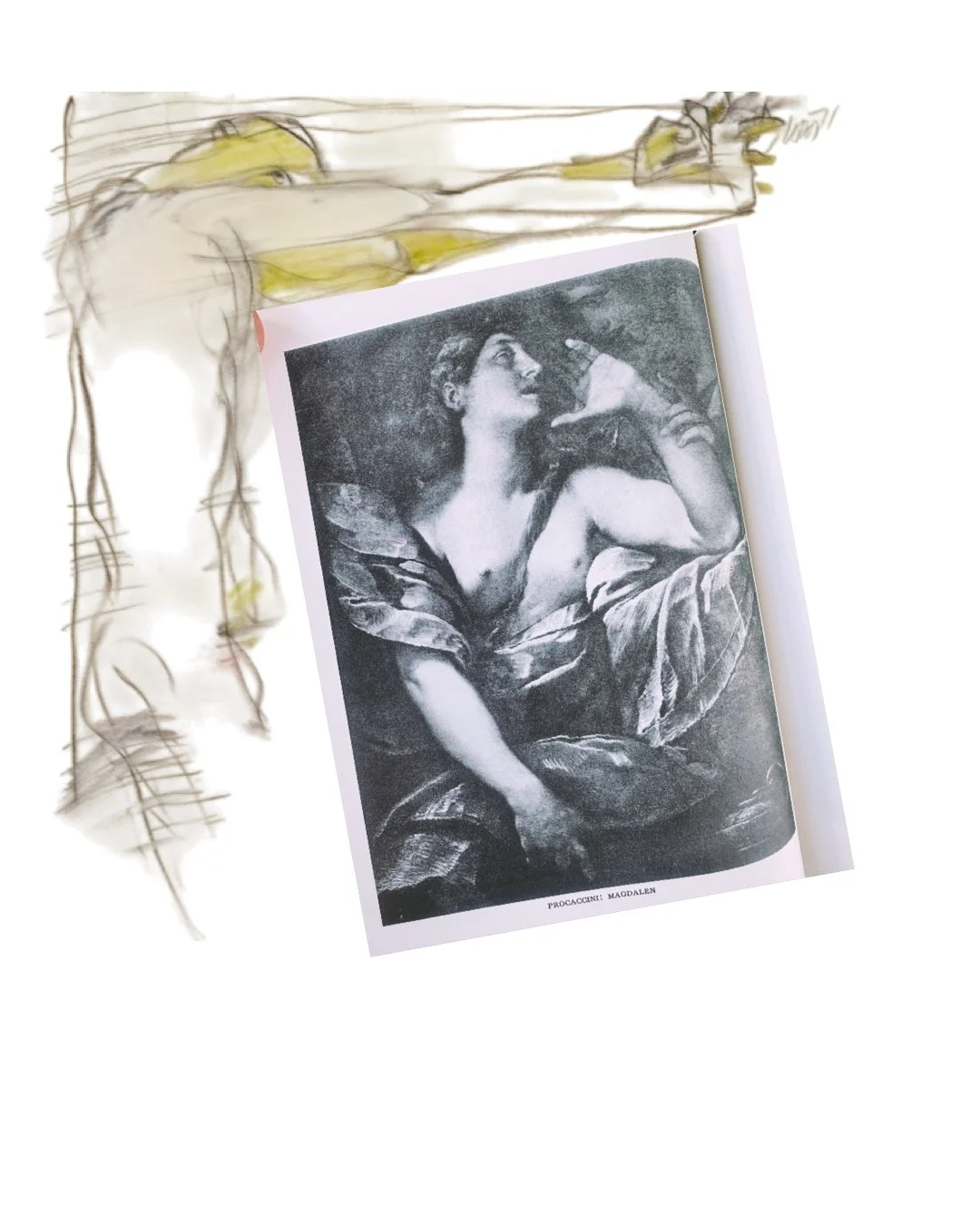

Mary Sully, Steinmetz, c. 1935.

Paul Bogard, ed. Solastalgia: An Anthology of Emotion in a Disappearing World. University of Virginia Press, 2023.