...the poor man you let become guilty.

— Goethe

Each thought has its own cell. But each cell can, in an instant, and apparently almost without cause, become a chamber, a legal chamber over which language presides.

— Walter Benjamin in an essay on Karl Kraus

POINTING.

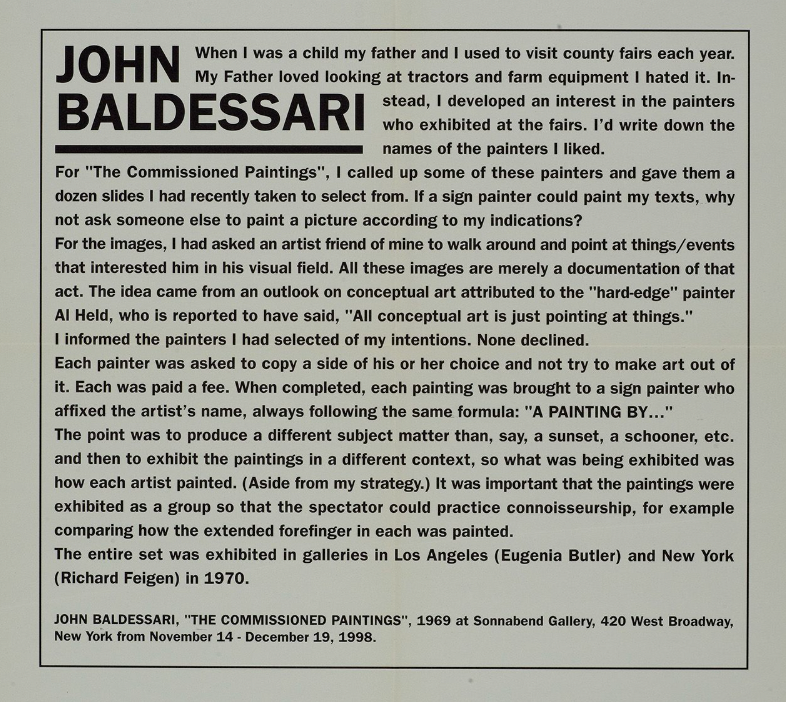

John Baldessari’s The Commissioned Paintings center the gesture known as “pointing,” which also happens to play a central role in the the developmental tests used to diagnose children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Al Held said that “all conceptual art is just pointing at things.”

It is said that young autists do not point to things that they desire.

It is said that pointing is part of pre-verbal language that begins in the first years of life, prior to the acquisition of words.

At what point does the conceptualization of the gesture becomes the gaze?

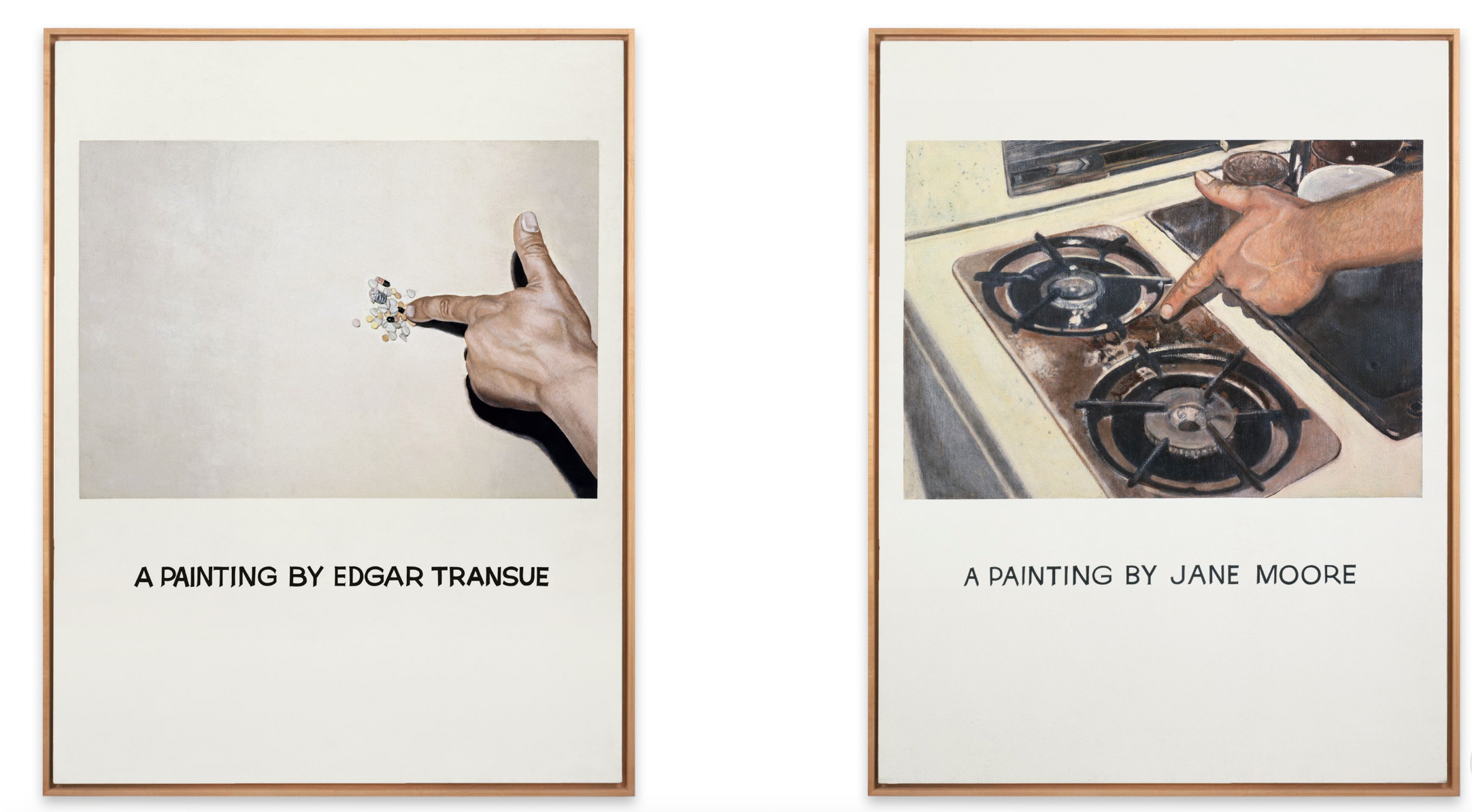

John Baldessari, Flying Saucer: Rainbow/Two Cyclists/Dog/Gorilla and Bananas/Chaotic Situation/Couple/Tortoise/Gunman(Fallen), 1992.

POINTLESS.

It is said that a raptor escaped from the NYC zoo and returned home a few weeks later only to due of a pigeon virus acquired in his ramblings outside the safety of the administered cage.

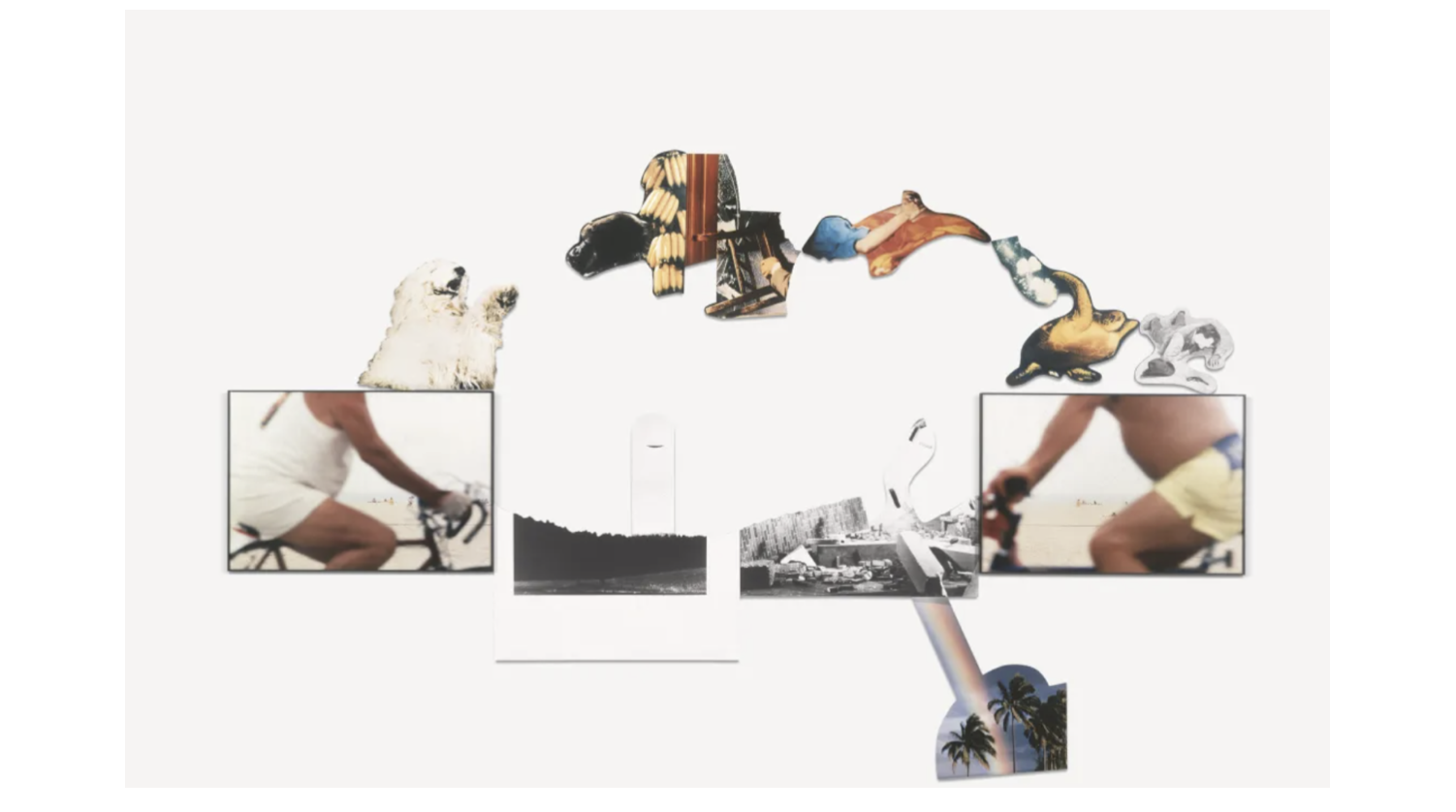

John Baldessari, Wrong, 1968.

THE POINTED FINGER OF JUDGEMENT.

Walter Benjamin said the “judging word expels the first human beings from paradise; they themselves have aroused it in accordance with the immutable law by which the judging word perishes - and expects its own awakening as the only, the deepest guilt.” The judging word returns in the affect of wretchedness: the plunging of guilt to the center of one’s being, leaving the person defined by that judging word. That judgement.

After devoting several notebook pages to a description of his writing desk, Franz Kafka must have paused and walked to the window. Surely two blankets of time passed in black boots. Maybe something involving a dog also happened. According to the next paragraph in his notebook, what he created is wretched:

“Wretched, wretched, and yet well intended. It's midnight after all, but considering that I'm very well rested, that can only serve as an excuse insofar as I wouldn't have written anything at all during the day. The burning lightbulb, the quiet apartment, the darkness outside, the last waking moments entitle me to write, even if it's the most wretched stuff. And I hastily make use of this right. This is just who I am.”

One who identifies with his creation may be damned by its judgement. While “its” may include the judgement of others, the most devastating judgement is that of the raven perched on one’s shoulder, urging you to finish the manuscripts with the help of a blowtorch.

Wretched the feeling of wronging the subject or failing the object.

Grotesque the shame upon encountering the ill-depicted desk.

Miserable the instant when passing the hallway mirror and noting the WRONG writ large on the forehead.

John Baldessari, For Barbara Rose, 1966–68.

POINTING WITH POSTAGE.

Little Ella, whatever do you look like, I've already forgotten you so completely that it's as if I'd never patted you.

Best Regards

Yours, Franz.

— Kafka’s first postcard, addressed to his younger sister

John Baldessari, Goya Series: This, That, or the Other, 1997.

PROJECTED POINT.

What follows is one of the unwritten stories that Kafka told Oskar Baum that “he had no hope, or even intention, of ever carrying out,” as recorded by Baum, who could be therefore be accused of doing something akin to telling it:

A man wants to create the possibility of a social event that tales place without anyone being invited. People see and speak to and and serve one another without knowing each other. It a a banquet where everyone can eat according to his taste without imposing on anyone else. Each person can arrive and leave whenever he pleases, he has no obligations to the host, and yet the host is always genuinely pleased to see him. When the man finally succeeds in executing his absurd idea, the reader recognizes that this attempt to rescue people from their solitude has in the end only produced— the invention of the coffeehouse.

Kafka’s unwritten stories differ from “projected works” in that they are utterly hopeless. They inhabit a timbre of hopelessness unique to Kafka in that they lack the proper ambition towards fruition. The singular instant of their projection is the entire point.

John Baldessari, Emoji Series: INT. BUSCH’S JEWELRY STORE – DAY MICHAEL Lugubrious movies of lost love, 2017.

TURNING POINT.

According to Gershom Scholem, the year 1921 marked “a turning point” in Walter Benjamin's life. Part of this turn was political in that “Critique of Violence” drew on Georges Sorel’s work to think about myth, religion, the law, and politics. The Weisse Blätter originally solicited the essay only to turn it down. Nevertheless, “Critique” appeared (awkwardly) in a sociological journal that same year.

Scholem said Benjamin “also tried hard to place his review of Bloch's book, of which he sent me a copy.” Scholem said Benjamin didn’t succeed in getting his review placed “due to the fact that this rather long essay was couched in such esoteric terms that the critic's own views— which were, after all, what mattered to the editors—remained virtually concealed.”

Scholem said the political was personal and the turning point couldn’t escape this imbrication. As Scholem told it:

In April 1921 the disintegration of Walter's and Dora's marriage became evident, and I was confronted with it during my visit. Between July 1919 and April 1921 I had known nothing about its status and had no idea of the extent of the deterioration of their relationship. Only when the explosion was already at hand (and afterward) did I learn about it in conversations with Dora. When Ernst Schoen renewed his amicable relationship with Walter and Dora in the winter months of 1921, Dora fell madly in love with him and for a few months was in an altogether euphoric mood. She discussed this quite openly with Walter. In April, the sister of his school friend Alfred Cohn, Jula Cohn, with whom Walter and Dora were already friends in the Youth Movement and before their departure for Switzerland (though I am not sure how close the friendship was) came to Berlin, and Benjamin saw her again for the first time in five years. He developed a passionate attachment to her and probably plunged her into confusion for some time before she realized that she could not commit herself to him. There developed a situation which, to the extent that I was able to understand it, corresponded to the one in Goethe's novel Elective Affinities.

When I came to Berlin, Walter and Dora let me in on this state of affairs and asked me to counsel and assist them as a friend in a situation in which both were considering marriage to someone else. Neither marriage materialized, but with this crisis the dissolution of Benjamin's marriage had entered an acute stage. That summer was a period of great tension and expectations. Both of them were convinced they had now presenced the love of their lives. The process that began at this time lasted for two years, and during that period Walter and Dora resumed their marital relationship from time to time, until from 1923 on they lived together only as friends, primarily for the sake of Stefan, whose development Walter followed with great interest, but presumably out of financial considerations as well. In the following years, until their divorce, this situation remained unchanged and was interrupted only by Walter's long trips and by periods in which he took a separate room for himself. From then on they went their separate ways, but they discussed with each other everything that affected them.

In the critical months when their marriage was beginning to break up they both, as far as I was able to witness, acted with a touching and loving friendliness toward each other. I never saw either treat the other person with such infinite considerateness and profound understanding as in those April days and the following year. It was as though each was afraid of hurting the other person, as though the demon that occasionally possessed Walter and manifested itself in despotic behavior and claims had completely left him under these somewhat fantastic conditions. My encounters in those days with them and Ernst Schoen—Dora came to Munich with him for a few days on her way to Breitenstein on the Semmering—are among the most beautiful that I remember.

During my remaining period in Germany, Dora was still greatly attached to Walter, and yet she started speaking about him in a new tone. Not that she doubted his gifts and his genius that meant so much to her, but she began to speak about features that had never before been voiced between us, including her experiences in the marriage. She labeled Walter a person suffering from an obsessive-compulsive neurosis, and this came as a surprise to me, for both of them had great reservations about psychiatric terminology. Later I heard this term from her on a number of other occasions, though I could not really corroborate this diagnosis on the basis of my own experience. Dora, a very sensuous woman, said that Walter's intellectuality impeded his libido. Breaking away from his intellectual sphere, to which she was to remain attached for a long time to come, proved very difficult for her and brought about a radical change in her life.

Later I spoke with several other women who personally knew Walter Benjamin very well, including one to whom he proposed marriage in 1932. They all emphasized that Benjamin was not attractive to them as a man, no matter how impressed or even enchanted they were with his intellect and his conversation. One of his close acquaintances told me that for her and her female friends he had not even existed as a man, that it had never even occurred to them that he had that dimension as well. “Walter was, so to speak, incorporeal.” Was the reason for this some lack of vitality, as it seemed to many, or was it a convolution of his vitality (which often enough burst forth in those years) with his altogether metaphysical orientation that gained him the reputation of being a withdrawn person?

Scholem pointed to Benjamin’s character as the source of his personal failings. This pointing grew more vociferous after his friend’s sudden death. Perhaps it is beside the point to wonder if Scholem envied Benjamin’s inability to commit to ideology, given Scholem’s own tendency to commit himself things that felt like popular movements. Unlike Benjamin, Scholem took himself to be “going somewhere,” and the sheer fact of his goingness enabled him to commit to Zionism without entirely subscribing to its tenets. Like many intellectuals, Scholem wanted to be famous. Unfortunately, Arendt (the woman whom he alleged to be a “self-hating Jew” in diaspora publications) believed Benjamin’s writing deserved be to be read. And she had considered Scholem to be a friend. In a strange turn of events, the man who was going nowhere wound up being translated into English while the man with a pronounced sense of destination lingered on university shelves to emerge, however briefly, at parties and social events during the era I call My Time Among the Straussians.

ONE POINT.

At one point, Benjamin said that "to be in the possession of truth is sufficient justification for one's claim to a living.”

According to Kafka, one of the compartments in his writing desk contained the following: “old papers that I would have thrown away long ago if I had a wastepaper basket, pencils with broken-off points, an empty matchbox, a paperweight from Karlsbad, a ruler with an edge that would be too bumpy even for a country road, a lot of collar buttons, dull razor blades (the world has no place for them), tie clips, and yet another heavy iron paperweight.”

The broken-off points strike me as the most interesting ones.

*

Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith, eds. Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing (Northwestern Univ. Press, 2011)

Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship (NYRB Classics)

Susan Buck-Morss, “The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore,” New German Critique, no. 39 (Fall 1986)

Walter Benjamin, “On language as such and on the language of man”