“the withness of the body”

— Delmore Schwartz’s epigraph to the poem “The Heavy Bear Who Goes With Me”

BAUDELAIRE

When I fall asleep, and even during sleep,

I hear, quite distinctly, voices speaking

Whole phrases, commonplace and trivial,

Having no relation to my affairs.

Dear Mother, is any time left to us

In which to be happy? My debts are immense.

My bank account is subject to the court’s judgment.

I know nothing. I cannot know anything.

I have lost the ability to make an effort.

But now as before my love for you increases.

You are always armed to stone me, always:

It is true. It dates from childhood.

For the first time in my long life

I am almost happy. The book, almost finished,

Almost seems good. It will endure, a monument

To my obsessions, my hatred, my disgust.

Debts and inquietude persist and weaken me.

Satan glides before me, saying sweetly:

“Rest for a day! You can rest and play today.

Tonight you will work.” When night comes,

My mind, terrified by the arrears,

Bored by sadness, paralyzed by impotence,

Promises: “Tomorrow: I will tomorrow.”

Tomorrow the same comedy enacts itself

With the same resolution, the same weakness.

I am sick of this life of furnished rooms.

I am sick of having colds and headaches:

You know my strange life. Every day brings

Its quota of wrath. You little know

A poet’s life, dear Mother: I must write poems,

The most fatiguing of occupations.

I am sad this morning. Do not reproach me.

I write from a café near the post office,

Amid the click of billiard balls, the clatter of dishes,

The pounding of my heart. I have been asked to write

“A History of Caricature.” I have been asked to write

“A History of Sculpture.” Shall I write a history

Of the caricatures of the sculptures of you in my heart?

Although it costs you countless agony,

Although you cannot believe it necessary,

And doubt that the sum is accurate,

Please send me money enough for at least three weeks.

“I think it is the year 1909.” The narrator is sitting in a darkened movie theatre, watching a newsreel of his parents as they stroll on the boardwalk at Coney Island, four years before his own birth. As the film unfolds, Schwartz listens to his father boast of how much money he has made, “exaggerating an amount which need not have been exaggerated,” and starts to weep, overcome by his father’s suspicion that “actualities somehow fall short, no matter how fine they are.” The son, transfixed by the tragedy unfolding before his eyes—his parents’ unhappy marriage, his father’s lost fortune in real estate, his mother’s lonely widowhood—leaps up from his seat in the darkened theatre at the very moment his father is about to propose to his mother and shouts, “Don’t do it! It’s not too late to change your minds, both of you. Nothing good will come of it, only remorse, hatred, scandal, and two children whose characters are monstrous.”

— James Atlas recounting Schwartz’s short story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities”

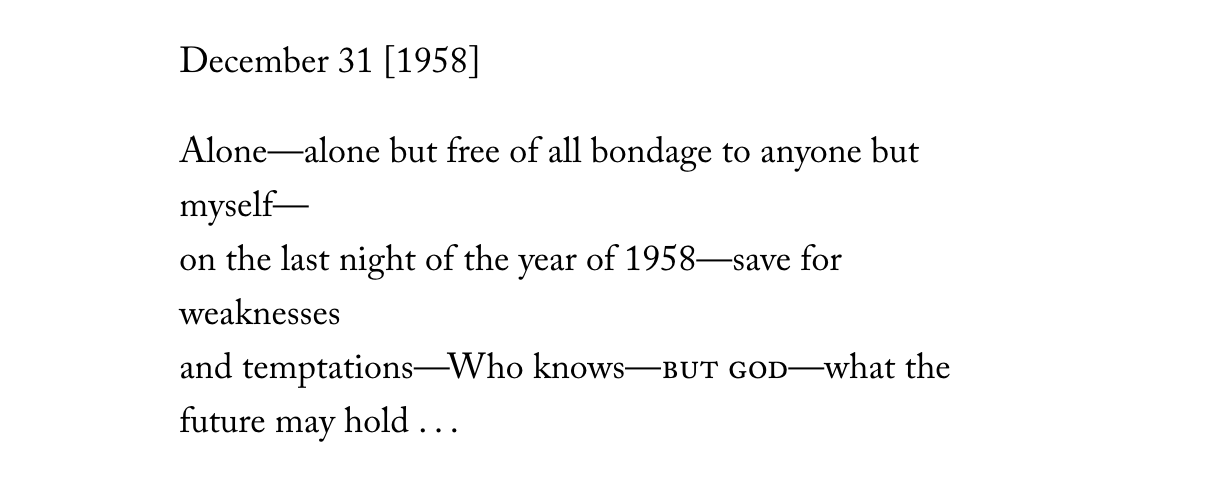

It was pleasant to learn that you expected our correspondence to be read in the international salons and boudoirs of the future. Do you think they will be able to distinguish between the obfuscations, mystifications, efforts at humor, and plain statements of fact? Will they recognize my primary feelings as a correspondent—the catacomb from which I write to you, seeking some compassion? Or will they just think that I am nasty, an over-eager clown, gauche, awkward, and bookish? Will they understand that I am always direct, open, friendly, simple and candid to the point of naivete until the ways of the fiendish world infuriate me and I am forced to be devious, suspicious, calculating, not that it does me any good anyway?

— Delmore Schwartz to James Lauglin, 1951

Much of the writing life occurs by chance. Someone knows someone who introduces someone to their agent. Someone works for the publisher of New Directions. Someone’s best friend knows the fiction editor at New Yorker. Being in the right place at the right time (usually NYC). Knowing the right people. Provoking the right editor. The unpredictable route to publication is rarely pure or uninflected by inner circles and networks. Meritocracy is our favorite lie, and we sustain it with a mixture of guilt and the particular sense of entitlement inherited as privilege.

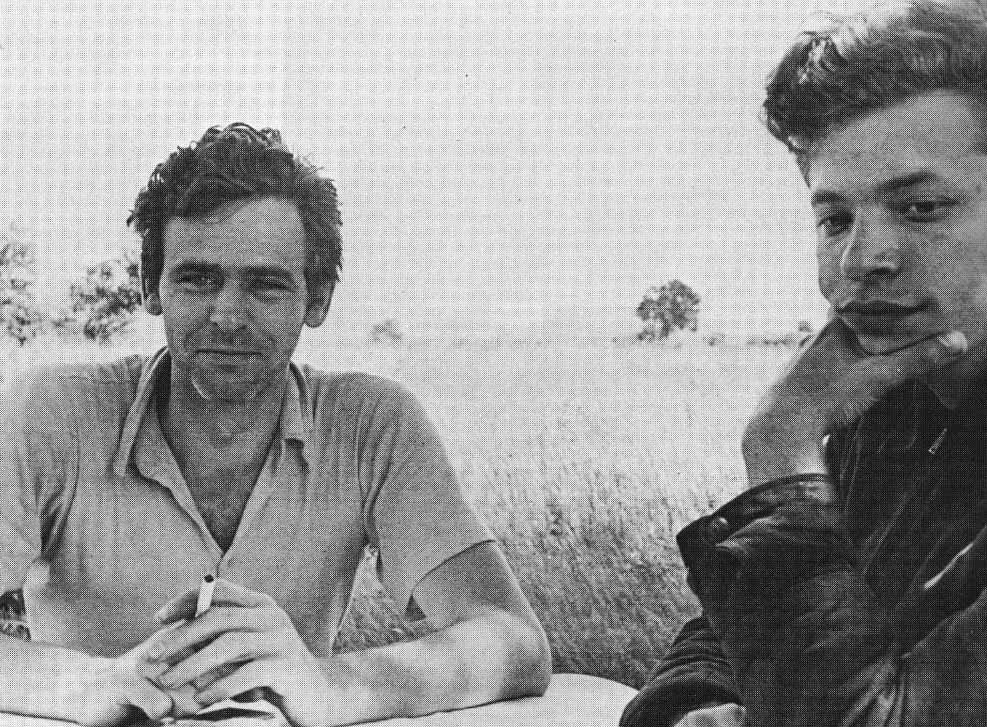

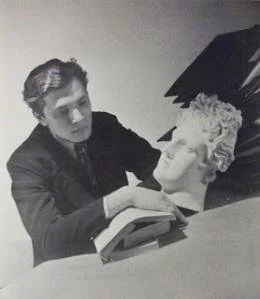

Interviews ask us to consider the writing life, or to speak of our own, and the Archimedean point is a temptation, as the statue of eternity lures us with its smooth surface from the margins. The truth is that writing resembles death in that we never know when it will end the book we haven’t finished. Nor do we know if the book will live beyond us, or whether our unpublished books will fall into the hands of friends that have the time and energy to push them into the world. Luck, friendship, and uncertainty . . . It was Schwartz’s friend, Dwight Macdonald, who preserved the papers and random materials present in Schwartz’s hotel room at the time of his death— and this only occurred because Dwight’s son ran into the owner of a moving van company in a bar who informed him that the hotel room was being cleared.

*

Delmore Schwartz, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” (Partisan Review, Autumn 1937) — read by Lou Reed

Delmore Schwartz, “In the Naked Bed, In Plato’s Cave” (1967)

Delmore Schwartz, “The Heavy Bear Who Goes with Me” (1967)

James Atlas, “Delmore Schwartz and the Biographer’s Obsession” (New Yorker, August 2017)

Walker Percy, The Moviegoer