I am not interested in the prick per se. I am interested in prose.

— Wayne Koestenbaum, “Darling’s Prick”

First things first.

— David Shields, “Life Story”

“A KISSPROOF WORLD OF PLASTIC TOILETSEATS TAMPAX AND TAXIS”

Someone in the apartment to my left applies his drill to the wall in between us, forcing the hard buzz into the drift of my reading, altering the smooth of images, and I am reminded of how perception in poetry depends on pacing, on the rate of movement and the appearance of speed bumps, sirens, pauses.

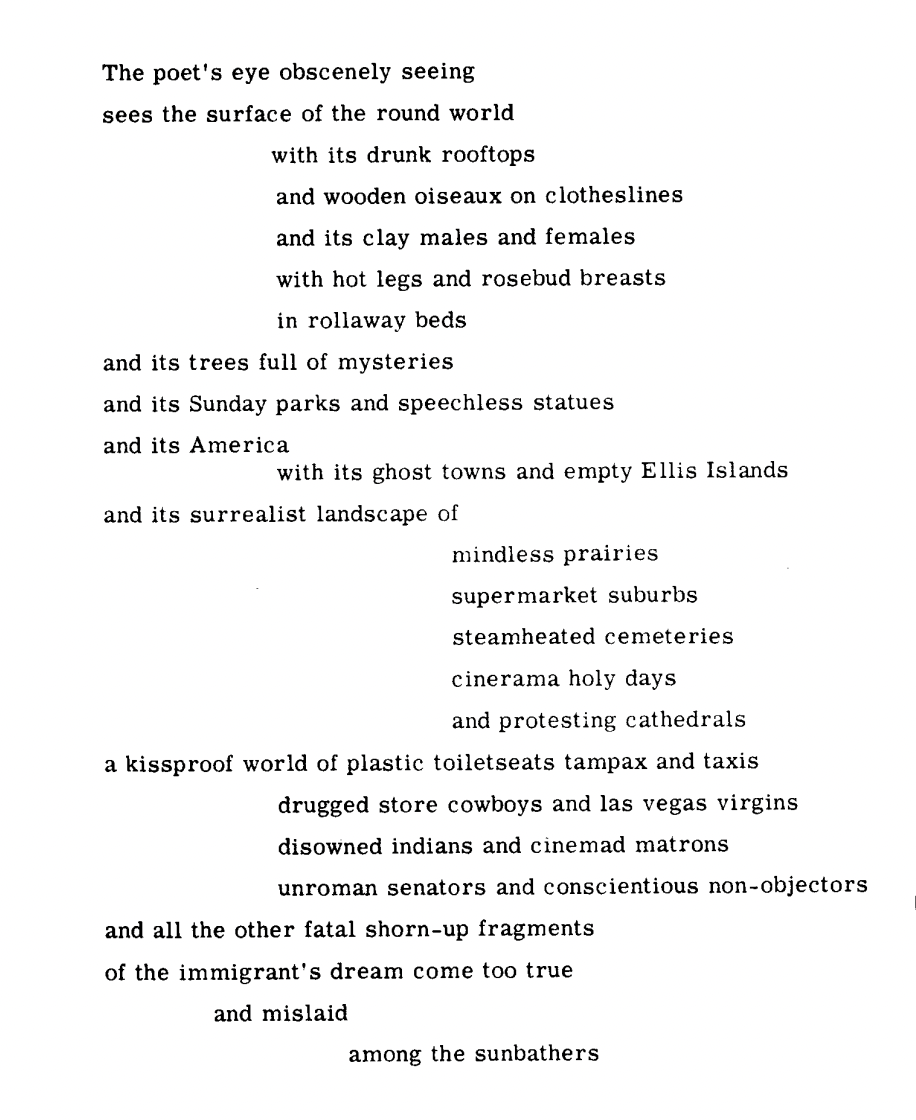

It is morning. Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind drags its “drunk rooftops” into the light. “The poet’s eye obscenely seeing” — tracking, collecting, studying — “hot legs and rosebud breasts”…

The teens are among the sunbathers today, their voices retreating as they move towards the beach; a clump of busy vowels to which no consonant can cling by the time the teens’ shout ascends to where I stand, watching, from the balcony. Ferlinghetti builds from association and accumulation: the images link to each other mnemonically, like the simple dogs and cats on those flashcards once used to teach phonics.

I don’t know if phonics gets taught anymore in this land where lifestyle has become a religion. The joggers return from their runs, sweat laureling their foreheads as if to regale a moment of glory before they reenter the world of their ordinary lives, and the chaotic routines of family. These joggers whom I will never understand— (What is there to understand about humans who run in circles, after having already admitted to themselves that they want to leave, and going so far as to purchase uniforms and expensive gear in pursuit of this goal but then refusing to commit to the continuance of that gesture, electing for a ‘daily run’ over the uncertain marvel of running away completely?) — wear that halo of sweat with its undertones of labor and industry alongside “all the other fatal shorn-up fragments”

and its trees full of mysteries

and its Sunday parks and speechless statues

and its America

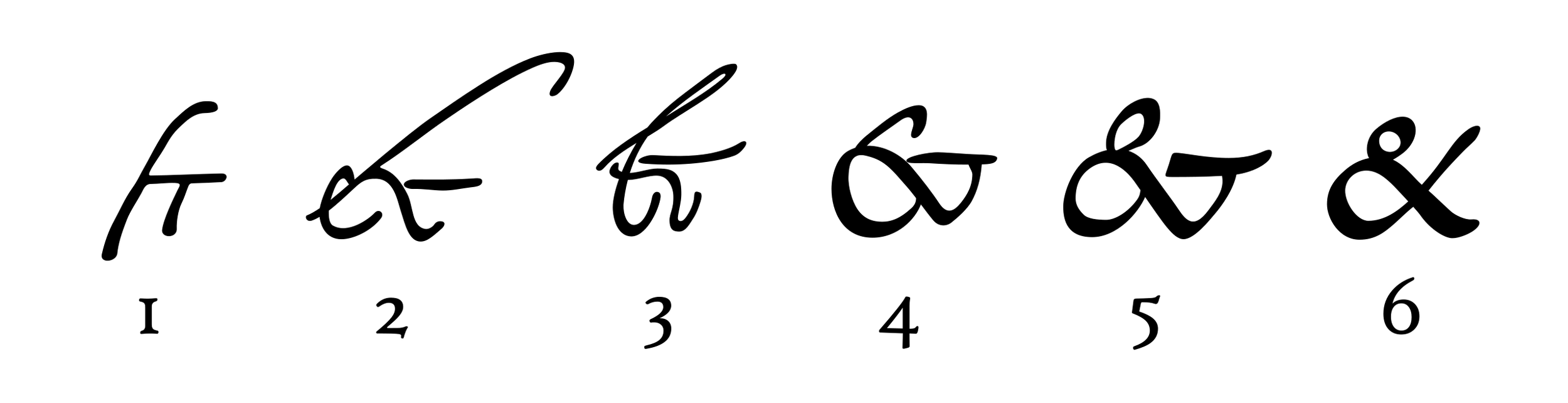

And this anaphora of “ands” turned into ampersands at sunset when I read a poem by Lucy Brock-Broido tweeted by a a fellow ‘American’ on a day when many Americans had planned their Labor Day weekends to coincide with the strenuous accomplishments of Self-Care alongside Family-Time, and the dash attempted to join unlike objects made poetry feel imperative to me, despite the distracting Ameri-can, the beat of that Ameri-can-can, the cancan of demands associated with national holidays in late capitalism.

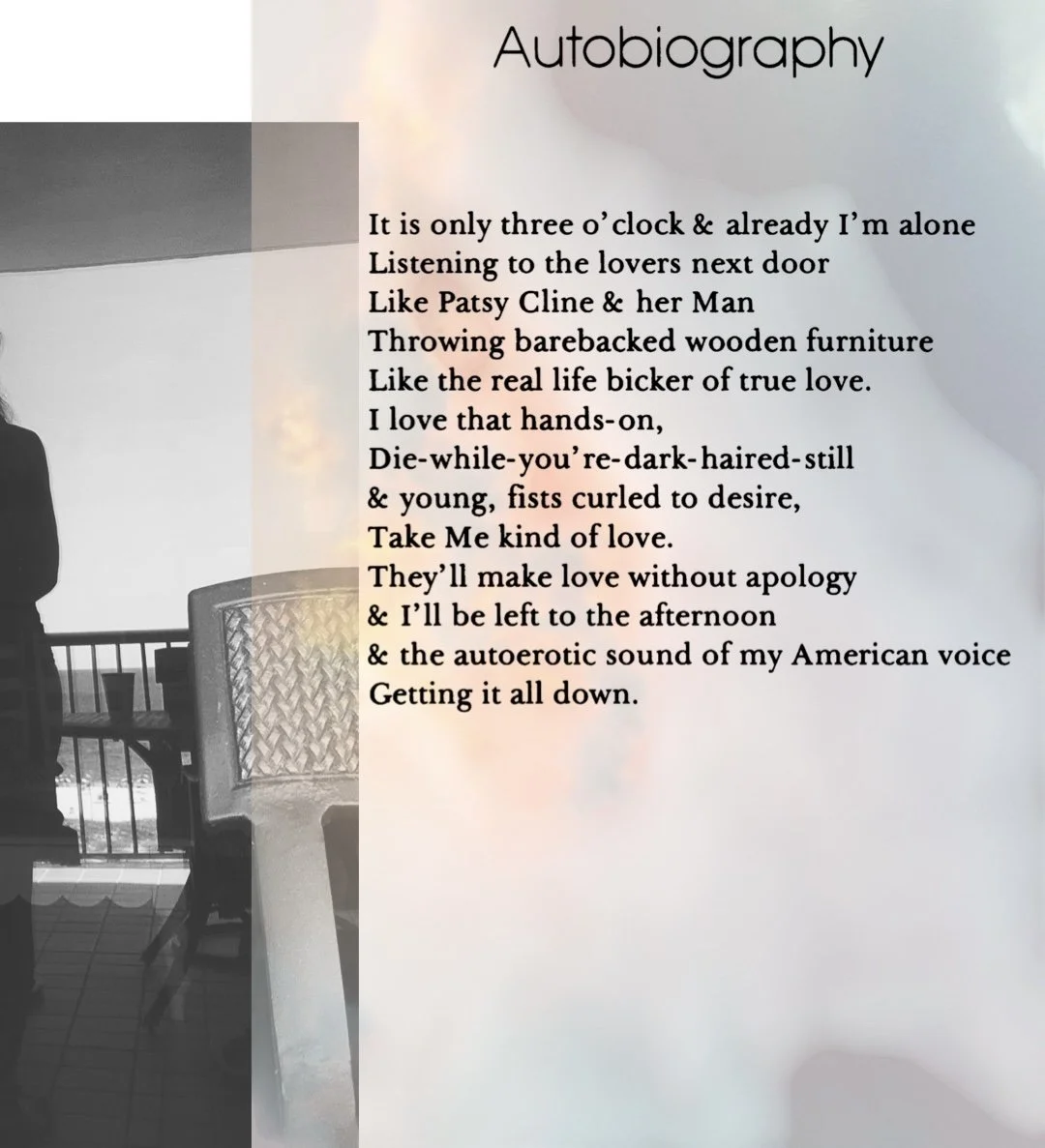

“& ALREADY I’M ALONE”

Maybe I was relieved to find Brock-Broido’s speaker announcing her condition of aloneness at the outset of the poem, telling us that she is alone

Listening to the lovers next door

Like Patsy Cline & her Man

Throwing barebacked wooden furniture

Like the real-life bicker of true love.

Two similes shoved up against each other violently, like a scene being remembered from a movie, a superposition insisting on similarity, investing in repetition, indulging the interpretive muscle known as loneliness, a muscle that works itself into a frenzy and then begins to hurt. Humans are the creatures for which that hurt signifies development, or the making of new muscles through repetitive motions, all this labor being the ride involved in fantasizing, that imaginative bench-pressing of other possibilities, taking us directly to the poem’s next moment:

I love that hands-on

Die-while-you’re-dark-haired-still

& young, fists curled to desire,

Take Me kind of love.

The emblems & stereotypes & associations are freely given here: her Man, the one that Loretta Lynn might stand by in a different song that has its own movie, rubs shoulders with the expression of abandon that communicates a demand, namely, Take Me. And an entire line linked up by that stitchmark of dashes which ties the urgency of temporality to not having grey hair, or not yet — then pausing at the line break which is (maybe) startled by that “still” — since it could insinuate a still-life, a genre of painted objects frozen in their domestic scenes like pears on a kitchen table . Or else a film still, ripped from the motion of moments galloping forward on a screen until the speaker freezes a frame and frees it from time’s ineluctable Progress in order to apply a Future, which is to say, a wild guess about else’s, in thrall to the Otherwise, wherein what comes next — “They’ll make love without apology”— leaves the knots unresolved between them. And it is precisely this irresolution which the poem presses (where to press is to apply pressure) across the cultural referents, building its stride from the discord between images and the sputters of mind remembering — recognizing the syntax of lovers as a series of sounds that require reading — and requiring the speaker to build from association, layering the lines with anaphora of ampersands, the & and & and & like soft pleas whispered into a phone receiver at midnight, a plea that reminds me of precisely what the motorist in Italo Calvino’s short story, “The Adventure of the Motorist,” sought to avoid when barreling down the highway to reach his lover’s home after an argument, speaking only the language of speed and momentum, the pure directionality of driving towards a destination unimpeded by the details of hurt feelings and recriminations that mobilize the plea, that particularly desperate form of desire given to language and lovers and midnight.

Where does that leave the speaker of Brock-Broido’s “Autobiography”?

& I’ll be left to the afternoon

& the autoerotic sound of my American voice

Getting it all down.

The ampersand’s logogram (&) looks nearly unrecognizable in italics (&,) — a reminder that signs depend on one’s familiarity with typeface and font and script, all of which begs the condition of recognition in semiotics.

“The only situation I can accept is this transformation of ourselves into the message of ourselves,” says Calvino’s motorist, intent on narrating the rain on the windshield as he careens down the dark highway towards the furious and wounded beloved or the “bicker” of thrown furniture and naked bodies collapsing into one another between invectives, moral claims, objections, fatal shorn-up fragments, and brilliant scenes they remember from screens.

*

Alessandro Sbordoni, “Anti-Hauntology & the Semiotics of the End” (&&&)

John Berger, Understanding a Photograph (Penguin Books)

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, A Coney Island of the Mind (New Directions)

Lucy Brock-Broido, “Autobiography”

Italo Calvino, Difficult Loves (New Directions)

Phil Collins, “A Groovy Kind of Love” (alternately, see Brock-Broido’s “Take Me kind of love”)