SILENCE

Along the city streets,

It is still high tide,

Yet the garrulous waves of life

Shrink and divide

With a thousand incidents

Vexed and debated:—

This is the hour for which we waited—

This is the ultimate hour

When life is justified.

The seas of experience

That were so broad and deep,

So immediate and steep,

Are suddenly still.

You may say what you will,

At such peace I am terrified.

There is nothing else beside.

T. S. Eliot

A glissando in the pigeons of Bucharest recurs in waves, and wavers through the simple end-rhymes of Eliot’s “Silence” only to be pulled into language by one of Robert Schumann’s greatest pieces, the Ghost Variations . . .

According to legend, on February 17, 1854, Robert Schumann heard angels dictating a musical theme to him and immediately wrote down this theme. A few days later, on the 22nd or 23rd, Schumann started writing variations on this theme.

Five days later, at 2 pm on February 27, Schumann lept into the iced waters of the Rhine river and attempted to drown himself. He lived because some boatmen spotted him and dragged the composer safely to shore.

No one can say what Schumann was thinking when he climbed out of bed on the following day, having survived his attempted suicide. No one can know what drove him to return to the Ghost Variations in an effort to complete them.

The Geistervariationen (“Ghost Variations”) are Schumann’s last work. The following week, Schumann voluntarily committed himself to an asylum in Endenich, where he would die just a little over 2 years later.

To note, briefly, the way the final three lines of Eliot’s poem refuse to settle into a single meaning:

You may say what you will,

At such peace I am terrified.

There is nothing else beside.

The terror of peace is cinched to the efficiency of ending, and the poem’s speaker resists this, the way the Ghost Variations resist the conclusive peace of the piece’s final passage in Schumann’s Ghost Variations.

Such an exquisite ending. Hand on my heart.

Schumann’s Ghost Variations cling to the ear: their intimacy is audible. And while this intimacy is characteristic of Schumann’s final pieces, he accomplishes it by narrowing the soundscape and adhering closely to original theme, building precariously and elliptically from its resonances, refusing to abandon the original melody entirely.

“There is nothing else beside,” wrote Eliot, lingering near the expectation of a plural “besides” before rejecting it for the intimate spatial proximity of “beside.”

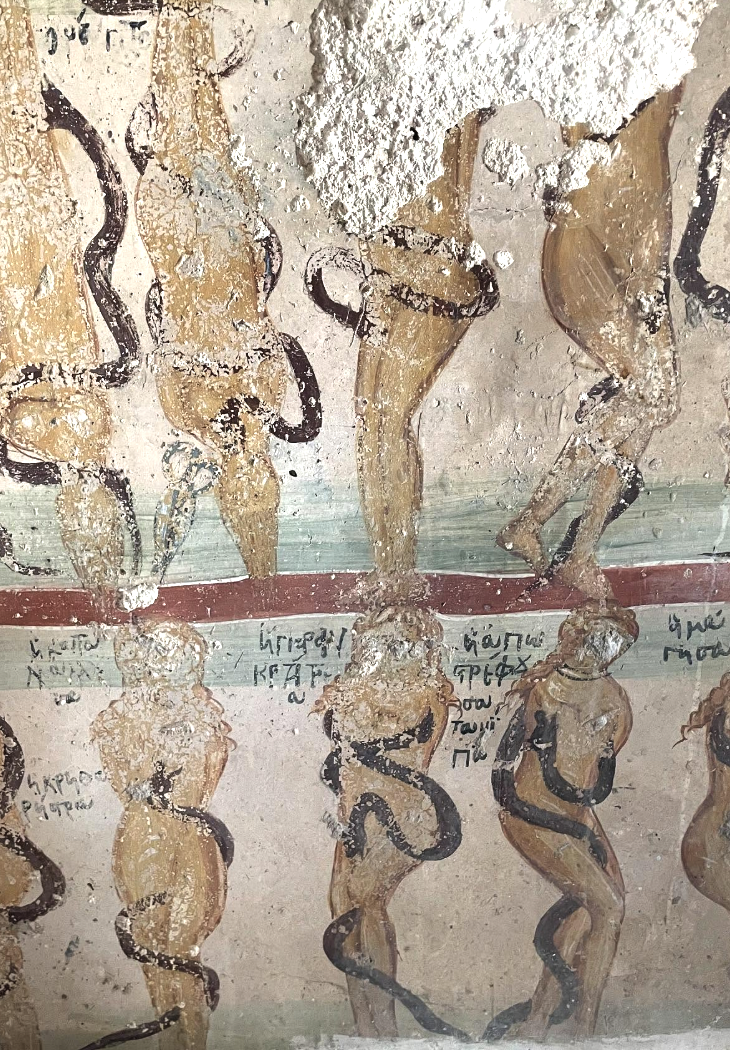

The snake encircling the bodies of the faceless women in a fresco from the chapel in Crete that haunts my imagination for the past week, and an excerpt from Agustín Fernández Mallo’s The Book of All Loves:

Inertia (“there are no doors”) and repetition (“we are the doors”), the he-sees/she-sees seesaw that Mallo works throughout the book of all loves that cannot be exhausted.