Every reading occurs within a structure (however multiple, however open), and not in the allegedly free space of an alleged spontaneity: there is no ‘natural,’ ‘wild’ reading: reading does not overflow structure; it is subject to it: it needs structure, it respects structure.

— Roland Barthes, The Rustle of Language (t. by Richard Howard)

Desire to replace ordinary reading (in which you have to go from section to section) with the spectacle of a simultaneous speech where everything would be said all at once, without confusion, in ‘a total, peaceful, intimate and ultimately uniform flash.’

— Maurice Blanchot, “Joubert and Space” (t. by Charlotte Mandell)

1.

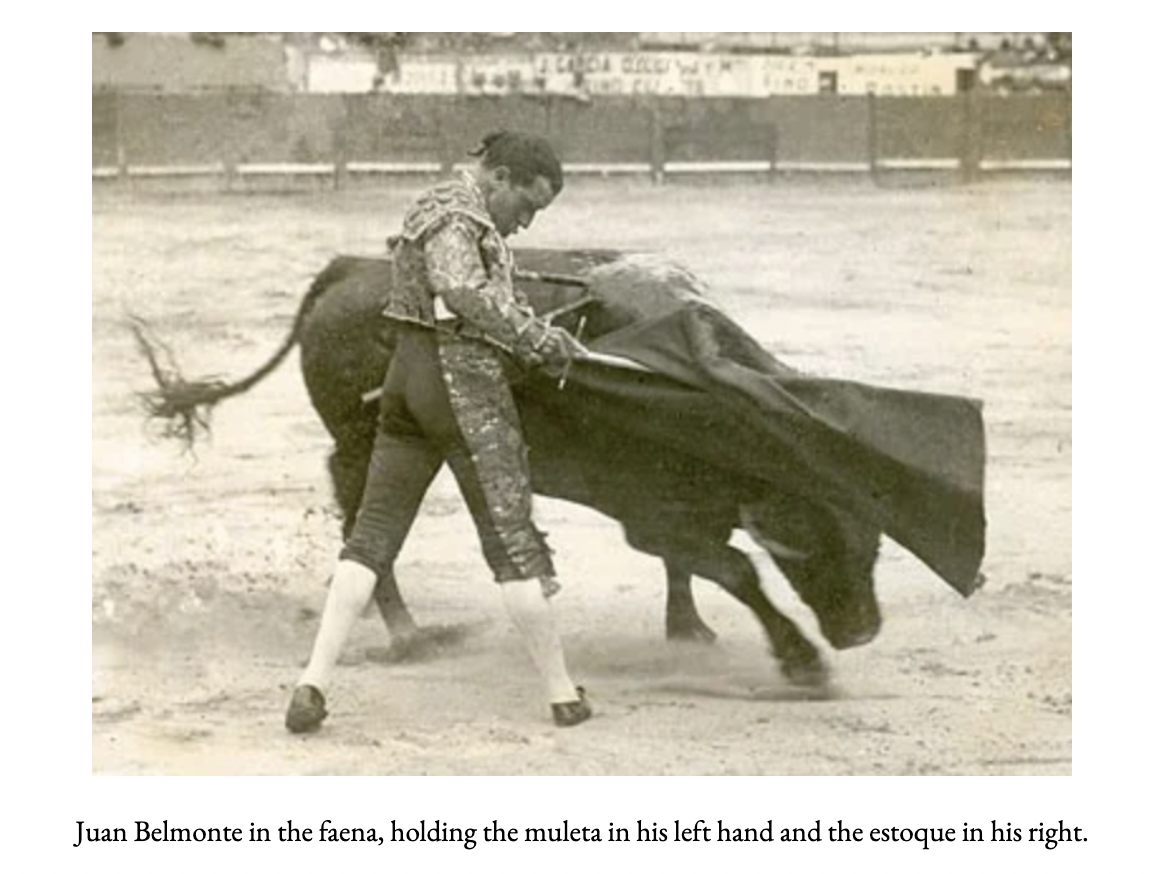

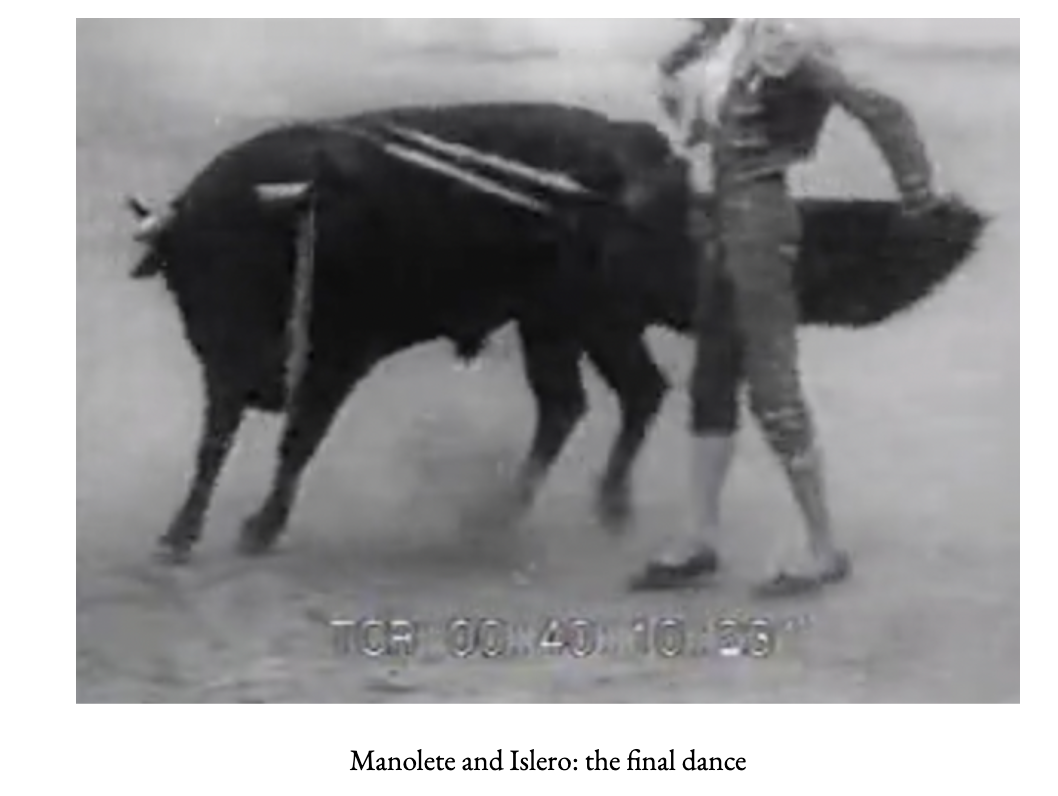

Sibiu, June 2025. I went to the Este Film Festival to catch a screening of Albert Serra’s Afternoons of Solitude (2024). Serra’s reputation as an enfant terrible of European cinema rests on his refusal to clarify boundaries between documentary forms and fictional ones, among other things, of course. The film is a repetitive loop of sheer brutality: the performance of masculinity set against the ‘natural’ animality of the bull, no commentary on bullfighting itself, just the visceral presentation, partly inspired by Francisco Goya’s paintings. There are 14 bullfights in total, and it is a testament to Serra’s enervating cinematography that one manages to sit through all of them.

The beginning: no sound, an austere red in the opening credits, an expectancy. Cut into a scene saturated in darkness: a black night, sown wheat in the wild, and a single bull, breathing, just breathing— his fur glistening in patches, the silver hue of moonlight, a fusion of power and vulnerability —

2.

DC, early 2000’s. G and I stood outside the nonspecific Middle Eastern restaurant in DC that would later be buried beneath a strip mall. — But we could not have imagined that yet. Instead, in that particular moment, G described his summer experience, eyes narrowing as he looked into the near distance, a Merit menthol in his right hand. “I was in Pamplona, studying abroad,” G said. “My girlfriend of two years had dumped me in a phone call. And that's how it happened, during the Fiesta de San Fermín, the city was possessed. I joined strangers in the street, running between alleys . . . the encierro swallowed me. I'm saving up to go again, to be part of the running of the bulls.”

At the time, what I knew of Spain was limited to the rocky coastal areas, and the pink jelly shoes I wore to protect my bare feet from the sea urchins on the rocks. But G. was going back to run with the bulls. His passion for this sadistic ritual astonished me.

3.

In what was to be his final book, The Tears of Eros, Georges Bataille curated an arche of the erotic from images made by humans. He pauses near the Lascaux cave, trying to decipher them:

In the deepest crevice of this cave, the deepest and also the most inaccessible (today, however, a vertical iron ladder allows access to a small number of people at a time, so that most of the visitors do not know about it, or at best know it through photographic reproductions), at the bottom of a crevice so awkward to get to that it now goes under the name of the "pit," we find ourselves before the most striking and the most strange of evocations.

A man, dead as far as one can tell, is stretched out, prostrate in front of a heavy, immobile, threatening animal. This animal is a bison, and the threat it poses is all the more grave because it is dying: it is wounded, and under its open belly its entrails are spilling out. Apparently it is this outstretched man who struck down the dying animal with his spear. But the man is not quite a man; his head, a bird's head, ends in a beak. Nothing in this whole image justifies the paradoxical fact that the man's sex is erect.

And there we have it: a man standing over a dead bull with an erection.

Nonsense, scoffs Bataille, refusing my hasty reading, dragging me, instead, into the darker caves of his his head. There is a veil here, Bataille insists, a paradox:

But in these closed depths a paradoxical accord is signed, an accord all the more grave in that it is signed in this inaccessible obscurity. This essential and paradoxical accord is between death and eroticism. Its truth no doubt continues to assert itself. However, no matter how it asserts itself, it still remains hidden. Such is the nature of both death and eroticism. The one and the other in fact conceal themselves: they conceal themselves at the very moment they reveal themselves.

We cannot imagine a more obscure contradiction.

4.

There is a season for death. The Spanish bullfighting season, la temporada, starts at the end of March and continues until early October. When the season ends, top matadors travel to Lima for the month-long Peruvian season before heading to Mexico City in December and January. Aspiring bullfighters, los novilleros, perform in Mexico only in the summer, whereas in Spain they perform from March to October.

5.

Sibiu, June 2025. [From the “Notes” document P kept on his iphone as we watched Serra’s Afternoons of Solitude.]

HE: I’m assuming the bulls are trained to respond to the calls being made by toreadors?

ME: Not really. This is supposed to be an amor fati scenario where neither bull nor matador see each other until the ring. And bulls are selected early on their lives: a bull that chosen for bullfighting is never allowed to see a human on foot, face to face, eye to eye, grounded so to speak until the corrida. The bullfighting bulls are raised separately, and field-hands only approach them on horses. They are raised totally wild in the field . . . as compared to their peers who are fattened in stalls for slaughter so that we can eat them.

HE: Why is he doing this?

ME: Most bulls favor one side so on the first cape run the matador attempts to feel out the bull’s weakness and preferences.

HE: Def machismo cult—you got balls, they’ll suck you off etc, locker room talk over nothing. The idea of this “as it is” presentation is obvi bullshit. No director does something like this without a clear point, imho.

ME: Probably true. For me the bullfight is what we do to men in some ways: epic masculinity meets its peak in this intensity, with the cheers of the audience and death at stake. But it is also not man to me, see, not men as I know them— just the cult of masculinity. The same man who is vulnerable and powerful and alone in his nakedness is different creature when trying to impress other men and prove his manliness. Masculinity isn’t real or sexy to me.

HE: But it is real. You say men egg it on, and that’s true, but women play a huge part in that cult. Women lionize this kind of man. Why do you want to watch this sort of movie? Why are we here? What part of this needs seeing?

ME: I want to understand what we do to men. I want to understand how gender is constituted by and from fear. Why is fear so central to relationality vis a vis gender?

6.

Birmingham, 2025. To raise money for his trip to Spain, G was giving tango lessons to retirees in L. A. I think of G again when looking at a photo of my parents dancing the tango; my mother’s hip glued to my father’s leg, as if lightning had seared them together. There is a splendid moment in Pedro Almodovar’s film, Volver, when our expectations are subverted— and we, the audience, are given to recognize or admit what we expected in the instance of disappointment. Almodovar prepares us for an Argentine tango of the sort that Carlos Gardel made famous in the 1930s, but what he delivers, instead, is Penelope Cruz performing the same song as a soulful flamenco.

In the margins of the corrida, flamenco reaches towards duende. Where the matador seeks to channel the spirit of his opponent, the bull, in order to anticipate his next move, the flamenco dancer seeks to connect with the dead and the absent. When duende is present, the dance is overcome; the dancer’s ecstasy fills the room. It is captivating. One becomes captive to it.

7.

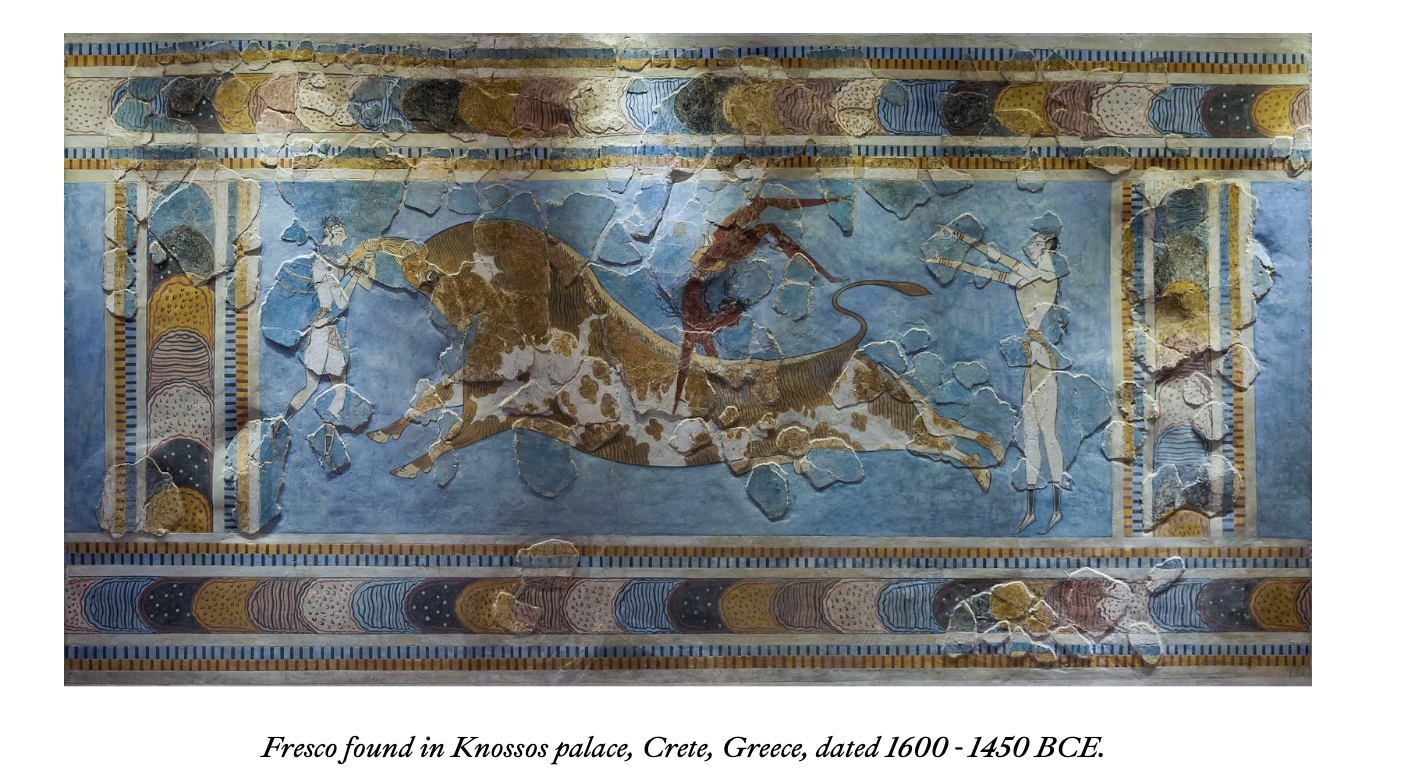

On the island of Crete, archaeological excavations revealed ancient Minoan frescoes (c. 1500 BCE) painted in relief on stucco. To create these frescoes, artists had to negotiate the height of the panel while simultaneously molding and painting the fresh stucco. The colors employed date the frescoes in late Minoan period: the skills for creating such art had already been shaped into methods, making them examples of "mature art" for the Minoans.

To speak of mature art in a civilization implies the end of that civilization as a known point.

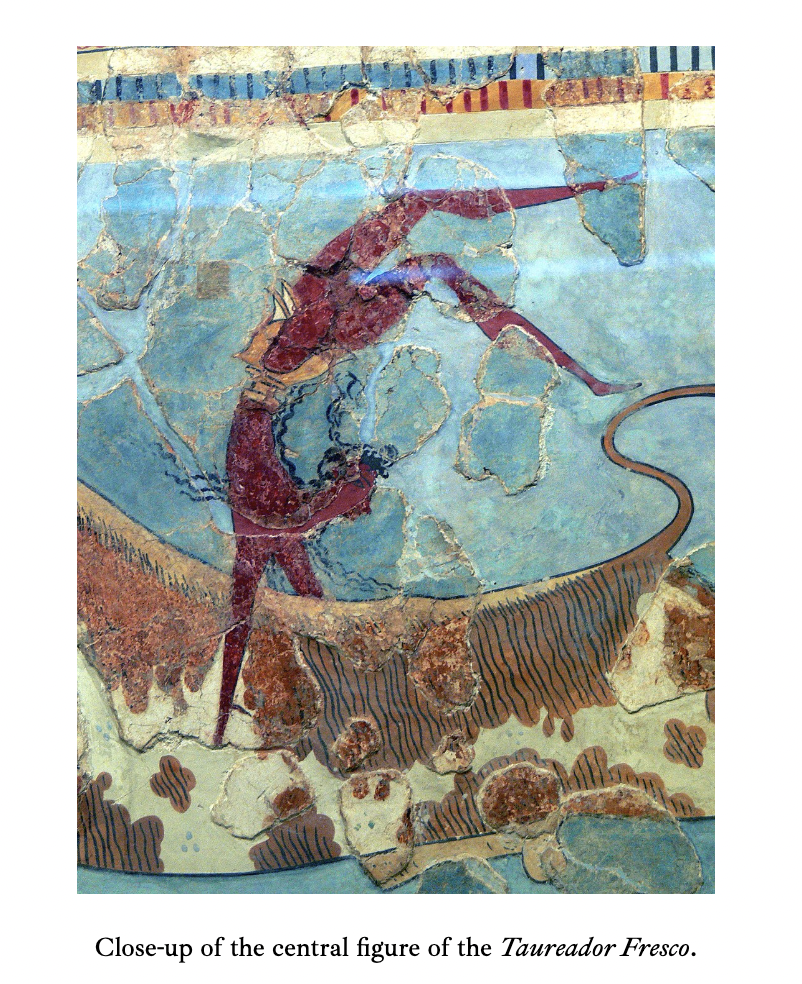

Late Minoan art used the polychrome hues – white, pale red, dark red, blue, black – visible in the Taureador Frescoes. In the scenes, young men and women play games with bulls, grabbing their horns and vaulting over them. Gender is identified by color, according to Minoan conventions that painted women with pale skin and men with dark skin. Social status is indicated in clothing and jewelry.

The frescoes appear as decorative motifs adorning a wall above a ceremonial bull-ring. It is speculated that an earthquake in the Late Minoan period destroyed the palace, causing flakes from the destroyed panels to fall to the ground from the upper story, landing near the east stairwell, which was already ruinous and likely unused.

The Taureador Frescoes don't depict events that occurred in actuality so much as celebrate a conventional trope known as "bull-leaping," a term scholars say continues to lack a viable definition. (“Although it vaguely brings to mind the act of jumping over bulls, the technique and the reasons for doing that remain obscure, a century after the discovery of the frescos,” writes Jeremy McInnerny.)

8.

Macedonian coins depict Artemis Tauropolos (“Artemis Bullrider”) mounted on a charging bull. The Boegia (or "Bull Driving") was held in Miletus, and included a bull-grappling contest. In my copy of Michel Leiris' Manhood, the novel is preceded by an essay titled “The Autobiographer as Torero.”

9.

In The Book of Imaginary Beings, Jorge Luis Borges closes his eyes and burrows into the Minotaur's labyrinth. “It is fitting that in the center of a monstrous house there be a monstrous inhabitant,” Borges writes, for:

Human forms with bull heads figured, to judge by wall paintings, in the demonology of Crete. Most likely the Greek fable of the Minotaur is a late and clumsy version of far older myths, the shadow of other dreams still more full of horror.

Harking back to the Minotaur’s cameo appearance at the start of Dante’s Inferno, in Canto 12, Borges suggests — in a disputed interpretation — that Dante draws on the depiction from the Middle Ages of the beast as a bull’s body with a man’s head.

Upon the summit of the rugged slope

There lay outstretched the infamy of Crete

Conceived by guile within a wooden cow;

And when he saw us come, he bit himself,

Like one whom frenzy has deprived of reason.

Just as a bull, when stricken unto death,

Will break his halter, and will toss about

From side to side, unable to go on:

Thus did I see the Minotaur behave.

10.

The early Christian church found its most potent rival in the cult of Mithra, a pagan god of Persian mythology that was widely worshiped in ancient Rome. Central to the cult of Mithra was the Mithraic ceremony that sacrificed a bull to honor Mithra’s legendary slaying of a bull, which was depicted in art throughout the Roman Empire.

Feeling threatened by idolatry and rituals of Mithraism, the Roman church opposed them. The Council of Toledo in 447 drew a line straight from the bull to Satan: “a large, black, monstrous apparition with horns on his head, cloven hoofs, hair, ass’s ears, claws, fiery eyes, gnashing teeth, and huge phallus, and sulphurous smell.”

11.

For ancient Greeks, the bull symbolized fertility and priapism. Zeus (or Jupiter) is depicted riding a bull while holding a phallic scepter in his hand. At some point in time, Zeus trades the scepter for a labrys, or double-bitted ax, so he can throw thunderbolts at those who displeased him. (To please a god—particularly an angry and jealous god who aspires to monotheism, eventually complicated enough to require clerics.)

After acquiring his thunderbolt, Zeus visited his lover, Semele, disguised as lightning. It should be noted that the Thracians held Semele to be the goddess of the Earth who sometimes went by the name, Gaia. In the Albertine museum in Vienna, you can find an etching from the 16th century by master LD which depicts her meeting the thunderbolts, receiving her lover, looking, obviously orgasmic and reminiscent of the ecstatic expression on the face of the ecstatic saints.

Human beings believe things. All humans live in relation to the expectations generated by those beliefs. We believe the sun will rise tomorrow, etc. Faith, as developed by religious institutions, is rational to the degree that it is structured by belief, and given mass through credos, rituals, and affirming slogans. Faith apprehends through recognition, and this is essentially rational, it isn’t thoughtful, but it is still rational. It has a system.

The problem for rationalism and faith is ecstasy. Rationalism cannot touch the sacred or be permitted to reconfigure thought. Ecstasy makes the inarticulate physical, palpable, immediate. The absence of words underscores the absence of divinity. The sound that does not signify points beyond signification, and meets us in what Bataille called the sacred moment, or the instance in which existence is ruptured and lacks transition or explanation.

12.

A sigh, a shudder, a moan, the cry of grief, the veil of the world rent open by the wail. The Kaddish attempts to organize grief by taming it, and making it pleasing to God. The lament orders grief, and prevents it from becoming eternally unfinished like the fragments. God doesn’t want the universe to be riven apart by the pain of humans. Priests want the Divine to remain articulable, ritualized, available for social transaction and accounting. Priests are careerists of the established religion. They are not seekers of the divine so much as hired representatives of the divine timing. And that is the primary difference between monks and priests.

Lazlo Foldenyi says in articulate sounds are “manifestations of ‘God’ turned audible, but also a form of Echo..” his is the sound that John Cage encountered in the anhedonic chamber, where the labor of the heart became the music of silence.

Orphic cosmogony picks up from Hesiod’s Theogeny, after the clash of the titans, when the first human emerged from the ashes and cinder left behind after the Titans, were struck by lightning. The Titans birth, like that of the Dionysus, whom they killed, is born from the devastation rot by lightning. The Christian and Jewish god creates from dirt and language, while the Orphic God creates from ash, from the remnants of burnt materials, from the fragments of what lived, from the poetry manuscript. Lightning, for the ancient Greeks gave the soul to the human body, just as it unifies the sky and the earth. When Asclepius had the audacity to resurrect the dead, Zeus murdered him with lightning, a thunderbolt. In the battle of the Titans, Hesiod tells us that Zeus came from heaven and Olympus in the form of lightning. The heavens themselves hide Zeus‘s name: “ from Heaven and Olympus come forth with, hurling his lightning: the bold, flu, sick and fast from his hand together with thunder and lightning.” This destruction is summed up: “Astounding heat seized Chaos.”

13.

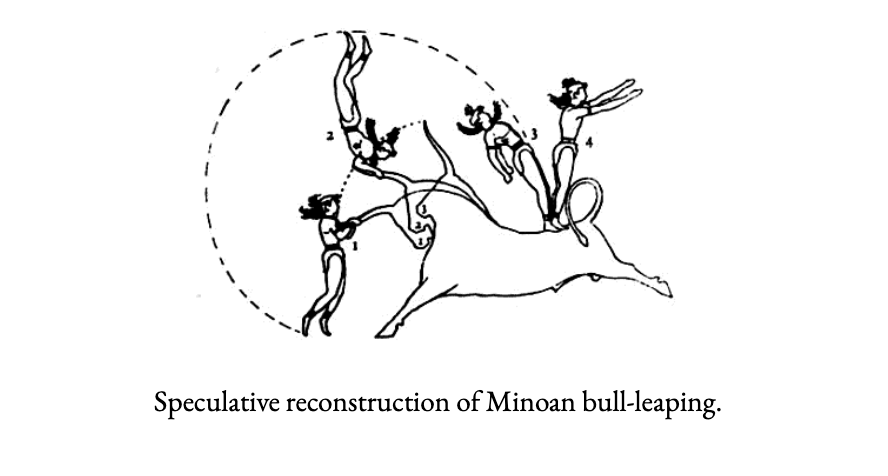

To return to Bataille and the ancients differently, with my head upside down, paraphrasing myself as well as the position from which some things are best glimpsed: seals and sealstones from the middle and late Minoan periods depict identical bull-leaping scenes where the leaper goes over the bull upside down. It’s not clear if the leaper is diving from above, leaping up from below, or being helped by another human or a pole. These scenes are taken as evidence of the Mycenaean Flying Leap, which occurred at full gallop. The bull’s legs are extended to show that he is motion while the woman stands in the front, holding his horns, preparing to leap over the bull or to land.

Today, Birmingham. Flashback of the opening scene from Serra’s Afternoons of Solitude: the redolent darkness filled by the heavy soundings of the bull’s breath, the freedom of that breath before being civilized .. . now I see Serra’s corrida bulls completely tied to the performance, just as the matadors and men are subject to the norms of masculinity, that brutish contestation of cajones and herms. . . . But how gorgeous and powerful, that naked man alone in the darkness, the air around him filled by his breath, the tempo of his concern and vulnerability, the animal who escapes, however briefly, the performances of convention in masculinity.

As to the question of how many more times . . .

To express the point in almost Heraclitean terms, we are dealing here with the difference between performing an action in the universe and ‘repeating’ it, that is, performing it ‘again’ in a universe already changed by the ‘first’ occurrence. Whereas classical arithmetic can assign no sense to the quote marks here, non-Euclidean arithmetic erases them by internalizing the distinctions they notate.

— Brian Rotman, Mathematics as Sign

*

Brian Rotman, Mathematics as Sign: Writing, Imagining, Counting (Stanford University Press, 2000).

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, trans. Lawrence Grant White (Pantheon Books, 1948).

Jay Wright, Presentable Art of Reading Absence (Dalkey Archive, 2008).

Joe Dassin, “Taka takata (La femme du toréro)”.

Jorge Luis Borges with Margarita Guerrero, The Book of Imaginary Beings, trans. Norman Thomas di Giovanni (E.P. Dutton, 1978).

Maurice Blanchot, “Joubert and Space,” The Book to Come, trans. Charlotte Mandell (Stanford University Press, 2003).

Reginald Dwayne Betts, “Remembering Hayden”.

Roland Barthes, The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (University of California Press, 1986).

Suzanne Dracuis. “The Macho's Marathon, the Major's Martyrology, and the Conqueror's Cavalry”, collected in Elektrik: Caribbean Writing. Calico Translation Series. Two Lines Press, 2023.