A religion is finished in the moment when it no longer generates heresies.

— Emil Cioran, 29 November 1959

1

Sibiu shutters with gorgeous loopy wiring, where loose wires are necklaces or ornaments for houses that carry sound and vibes in through the ancient walls.

Tuesday afternoon in Sibiu. June 2025.

At one point, while the family ate gelato, I scampered into the Humanitas bookstore and snagged a copy of Emil Cioran’s Caiete: 1957 - 1972, translated from the French into the Romanian by Emanoil Marcu and Vlad Russo. Admittedly, the translation loses a bit of velocity in the movement from one Latinate tongue to another: Cioran’s sparsity depends on the perambulations of syntax and phrasing, precisely what gets tangled in multiple translations. To put it another way, Cioran is intense and biting in the original Romanian; he is gorgeously rich with intonation in French; he is sublimely translated by Richard Howard; and yet middling when I try to revive him from the Marcu and Russo translations.

In the entries dated 14 July 1962, Cioran sits in Paris, looking back at Sibiu:

My feet sound different on every street, I think, comparing the beat of Sibiu’s cobblestone-steps to the asphalt of Bucharest.

2

Sibiu window: Dogwood flowers or orchids glimpsed through a lace curtain.

This date, 14 July 1962, takes Cioran back to his adolescence and childhood in the small village of Rășinari, which was was connected to Sibiu by a 8-km tram line through the Dumbrava Forest. Regular service for this tram line ended in 2011, and much of line was dismantled after 2013. The Rășinari Orthodox bishops' residence was built in the late 18th century. It incorporated pastoral and monastic traditions and provided a locus for the church in Transylvania. And, of course, Cioran’s father was an Orthodox priest, a man esteemed by the village, an esteem that Cioran simultaneously coveted and rejected.

3

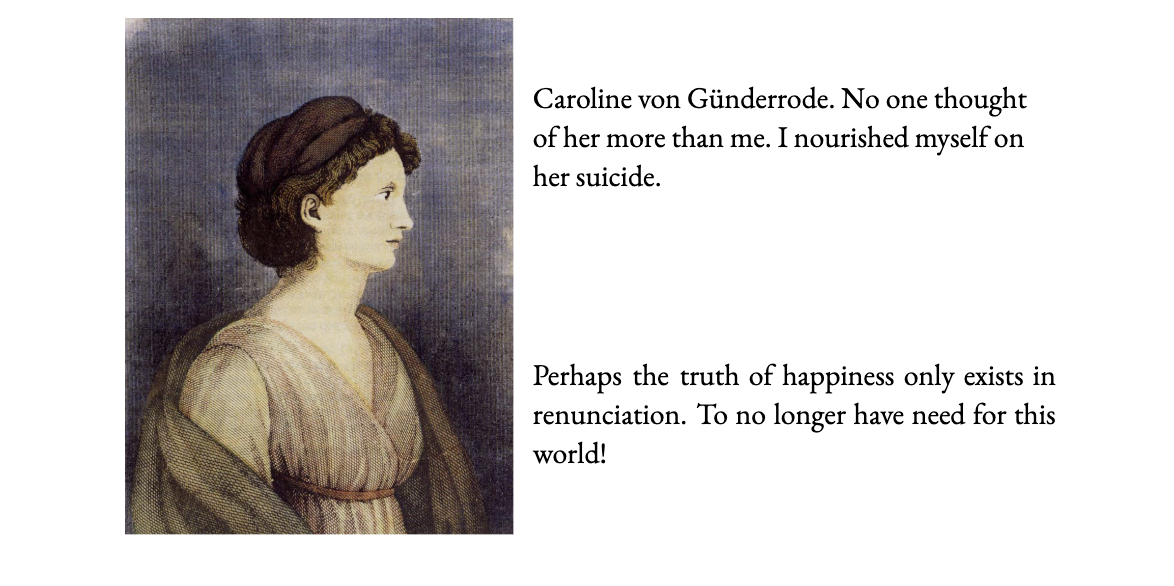

Cioran’s putative affection for Karoline Friederike Louise Maximiliane von Günderrode, a German Romantic poet who wrote under the pen name, Tian, was hardly unique. The female poet who dies by suicide due to “mental issues” and literary misogyny has always been fascinating to us, perhaps because these women dare to raise their voices and reveal the chafe-marks of the brindle. Their fury bothers and implicates us. We are torn between pity, chagrin, and contempt. In the confusion of our own affective responses, there is a tendency to lionize their deaths rather than the thing which mattered most to them, namely, their minds as written and felt.

Günderrode’s first poetry collection was published almost two decades after Bettina von Arnim’s epistolary novel, Die Günderode (1840) created the Caroline as a character in the public imagination. Christa Wolf also drew attention to Günderrode with her novel, Kein Ort. Nirgends (1978), imagining a fictional meeting between Günderrode and Heinrich von Kleist, another German author who died by suicide.

To his credit, Cioran never lied about envying the suicides. His early affinity with Stoic philosophers cast a covetous eye on the self-chosen death. “I cannot escape death, but at least I can escape the fear of it,” Epictetus declaimed. But if one can train the self to “escape the fear” of death, one can never entirely free life from the fear of how one’s death will hurt those who love you. Epictetus’ “I” is as solid and stiff as a Greek column: it exists in relation to the object it sustains, whether Parthenon or the ego, and has no truck with being-in-relation to others. But Stoicism wound up ornamental in Cioran’s writing, since he couldn’t entirely abandon the romance of mythology and religion. He never completely gave up the possibility of transcendence that came with releasing the world; he coveted the indescribable passion of the saints and the conviction of the martyrs.

The contradictions that create tension throughout Cioran’s texts are personal, which is to say, drawn from the author’s own obsessions and fears. That is why Cioran’s affection for Günderrode loves her death rather than her life. Certainly, one of the world’s greatest aphorists erases and ignores the poet whose life is given in her own hand, in her words and poetic texts, for the legend created by the novelist. Again, this should not be surprising: Cioran wasn’t a particularly insightful close reader of poetry. His philosophy and theory gravitated around myth and mythology: the eternal persona as sanctified by the meaningful death. His nihilism never stopped lusting for meaning.

As for Günderrode, her first poems were published under a male pseudonym. In her own words, as communicated in a letter to Kunigunde Brentano, she lamented her gender: “Why was I not born a man? I have no sense for feminine virtues, feminine bliss. Only that which is wild, great, radiant appeals to me.”

[These lines are so evocative of Marina Tsvetaeva’s verses and letters that I am tempted to speculate Tsvetaeva read Günderrode or von Arnim at some point while in exile, whether in Prague or Berlin. ]

4

The heretic cares more for the afterlives of ideas than for the human investment in a personal eternity. Each heresy nudges the door to a room open. In one of these rooms, Jacques Derrida sits at a small table in Paris, giving what could be his final interview, the progression of pancreatic cancer marked in the slightly yellow tint of his olive skin. There is no peace for the living, he suggests, for we are constructed from the tensions that animate the founding questions of philosophy, and not even death frees us from the legacy of those questions. Derrida tells the interviewer that the things which construct him are inseparable from the things that give him life. This contradiction which I cannot entirely assume is also what keeps me alive, or creates the conditions for my living, which is irrevocably bound up in thinking with and through the tensions that others will inherit.

5

Our final night in Bucharest required us to find a restaurant capable of seating almost twenty people at a single table with a courtyard. My cousin found a restaurant located in the old home of conductor Sergiu Celibidache. There is a particular void that one encounters in the mirrors that has held the bodies of your poetic subjects prior to their death—- the ghost of a self-encounter or self-critique, depending on one’s relation to reflections. I thought about Günderrode, contempt and Cioran’s sense of security in a language that ripped him from association with his roots.

A kneeling child in plaster, glimpsed between bars on Strada Plopilor (Street of the Poplars).