“The Geist has been known to gather up unwary authors somewhat as Zeus used to do with fleeing maidens and plump them with proper thoughts and attitudes. If writers were not the instruments of history, as often princes and politicians were, they were at least a showcase, a display of the spirit, like a museum's costumed effigies, if not one of its principal actors. Historical forces of this sort are as crudely imaginary as deities have always been, although probably not nearly as harmful since they cannot capture the imagination of millions the way divinities do. But of course the Geist can go behind a curtain and come back out as the Volk or the Reich instead of the Zeit.”

— William Gass, “The Death of the Author”

1. LETTER FROM BRUNO SCHULZ TO ANIA, DATED 19 JUNE 1941

Dear Ania:

I am still under the spell of your charming metamorphoses. I believe the reason they are so touching is that they exist so independent of your will, so automatic and unconscious. It's as though somebody substituted another person to take your place on the sly, and you, as it were, accepted this new person, took her for your own, and continued playing your part on the new instrument, unaware that someone else was acting onstage. Of course I am exaggerating the situation toward the paradoxical. Do not take me for naive. I know what happens is not altogether unconscious, but you don't realize how much of it is the action of more profound forces, how much is the doing of a metaphysical puppetry in you.

Add to this the fact that you are incredibly reactive, transforming yourself instantly into a complementary form, a wondrous accompaniment.... All this goes on outside the intellect, as it were, by some shorter and simpler circuit than thought, simply like a physical reflex. It is the first time in my experience that I have come across such natural riches that don't have enough space, you might say, within the dimensions of a single person and therefore mobilize ancillary personae, improvising pseudo personalities ad hoc for the duration of a brief role you are compelled to play. This is how I explain your protean nature to myself. You may think that I'm allowing myself to be taken in, that I'm pinning a deep interpretation on the playfulness of ordinary coquetry. Let me assure you that coquetry is something very profound and mysterious, and incomprehensible even to you. It is plain that you cannot see this mystery and that to you it must present itself as something ordinary and uncomplicated. But this is a delusion. You underestimate your possibilities and spoil the magnificent demonism of your nature by the ingenuous snobbery of saintliness. It isn't enough for you to be a demon; you want to be in addition and on the side—a saint, as if it were all that easy to combine these traits. You, with your fine nose for kitsch in art, lose your taste and instinct when it comes to the moral sphere and cultivate an unconscious dilettantism of holiness with a clear conscience. No—holiness is a thing of toil and blood that cannot be grafted onto a full and rich life like some pretty ornament. This dilettantism, by the way, is very charming and touching on the part of a soul who communicates with the pit from a yard away. With the Pit, capital P. I don't know how it happens, but you are playing with the keys to the Pit. I don't know if you are familiar with everyone's abyss of perdition or only with mine. In any case, you are moving with light, somnambulist ease on that cliff's edge I avoid in myself with fear and trembling, where the gravel shifts underfoot. I have to assume that you yourself are probably safe. You detach yourself lightly and delicately from the one who has lost his footing and let him slide into the abyss by himself. For a few steps you may actually pretend you are losing the ground under your feet, confident that at a certain point the parachute will open and carry you off to safety. With all this, you remain genuinely innocent and, as it were, unconscious of what you are doing. You are truly the victim, and truly all the guilt falls upon him who bears within him that abyss whose rim you carelessly set foot on. I know all the guilt is on my side, because the abyss is mine and you are only a sylph who has strayed into my garden, where it becomes my duty to keep your foot from sliding. That is why you should feel no self-reproach. You are always innocent whatever you do, and here a new perspective opens on your holiness. Your holiness in fact costs you nothing, for you are a sylph, and we are dealing not with dilettantism but with the superhuman elfin virtuosity of an entity that is not subject to moral categories.

Please come, secure and unthreatened as always, and don't spare me. Whatever happens, I endorse you in all your metamorphoses. If you are Circe, I will be Ulysses and I know the herb that will make you powerless. Of course, I may be just bragging, just being provocative.

Every day I wait till 6 P.M. I have a project for Sunday: let's meet in Truskawiec. I have a morning train there and an evening one back; we could spend the whole day there. Are you game?

Fond greetings, and thank you for coming.

Bruno Schulz

[The Sunday meeting Schulz suggested in the letter above fell on the day of Hitler's assault on the U.S.S.R., June 22. The next letter, written in September, is the first of Schulz's surviving letters written after the Nazi occupation of Drohobycz.]

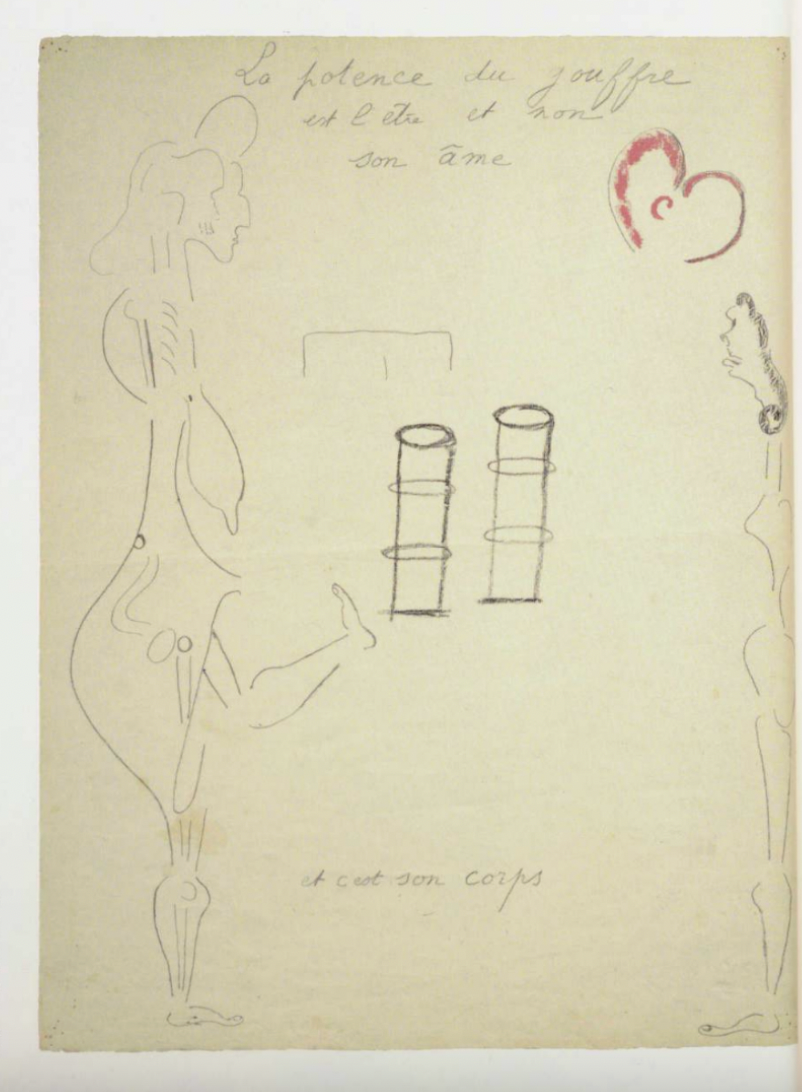

Antonin Artaud's sketch from October 1945. “The gallows for the abyss / is his being and not / his soul / and it is his body.”

2. CSZESLAW MILOSZ AND “THE ABYSS OF EXILE”

Translator Simon Leys’ essay, “In the Light of Simone Weil: Milosz and the Friendship of Camus,” trace Simone Weil's influence through the lives of two very disparate intellectuals. Czeslaw Milosz's own experience fighting against the Nazis in the underground altered his view of what was possible. "Naked horror" imprinted itself on his understanding of reality. As Leys writes: "The everyday order of our lives may seem to us natural and permanent, but it is in fact as fragile and illusory as the cardboard props on a theatrical stage. It can collapse in a flash and turn at once into black chaos. Our condition is precarious; even basic human decency can shatter and vanish in an instant," says Leys, before quoting a passage from Milosz’s The Captive Mind:

The nearness of death destroys shame. Men and women change as soon as they know that the date of their execution has been fixed by a fat little man with shiny boots and a riding crop. They copulate in public, on a small bit of ground surrounded by barbed wire - their last home on Earth.

Leys continues with Milosz's biography, noting that in the period following the war, like many Polish intellectuals who hoped that, by collaborating with the Communist regime, they might help it to reform itself, Milosz became a diplomat and was sent as cultural attaché, first to Washington and then to Paris." There, Milosz quickly learned that "serving a Stalinist regime" would cost him—would demand both moral and intellectual compromise—and, worst of all, would cultivate a deep sense of self-repugnance and cynicism.

"A man may persuade himself by the most logical reasoning that he will greatly benefit his health by swallowing live frogs; and thus rationally convinced, he may swallow a first frog, then a second, but at the third his stomach will revolt," Milosz wrote of this revulsion. In 1951, he abandoned his assignation and publicly broke with the Polish regime, taking that particular leap of no return into what Milsosz called “the abyss of exile, the worst of all misfortunes, for it meant sterility and inaction.” But he refused to relinquish the Polish language, his mother tongue, the speculative soil of a homeland he would cultivate in exile. Leys confirms that Milosz did all his writing in Polish, “with the exception of his private correspondence” which he conducted in French and in English, until his death. The first ten years of his exile were spent in France. There, “the prestigious title of an official representative of 'Democratic Poland, the French progressive' intelligentsia (under the pontificate of Sartre-Beauvoir), had warmly welcomed him; but as soon as it became known that he had defected, he was treated as a leper." In 1953, Milosz “made his situation even worse by publishing what was to become his most influential work, The Captive Mind, written not for a Western audience, but against it' - against its obtuse and willful blindness; the purpose was indeed to remind his readers that 'if something exists in one place, it will exist everywhere.” It was a self-indictment, though Americans who lacked background in the context of Iron Bloc dictatorships would easily misread it.

3. BEETHOVEN’S ABYSS

In conversation with Edward Said, Daniel Barenboim argued that music creates a greater sense of understanding about the world—it actively teaches rather than promoting escapism. "The Fourth Symphony of Beethoven is not only a means of escaping from the world,” said Barenboim. "There is a sense of total abyss when it starts, with one sustained note, a B-flat, one flute, the bassoons, the horns, and the pizzicato, the strings... and then nothing happens. There's this feeling of emptiness, only one note sticking there alone, and then the strings come in with another note, a G-flat, and at that moment, the listener is displaced.” He takes "this sense of displacement” to be “unique” in its capacity to alter the mind's relationship to itself:

When you hear the first note, you think, "Well, maybe this is going to be in B-flat." In the end it really is in B-flat, but by the second note you don't know where you are anymore because it's G-flat. From that moment alone you can understand so many things about human nature. You understand that things are not necessarily what they seem at first sight. B-flat is perhaps the key, but the G-flat introduces other possibilities.

There's a static, immovable, claustrophobic feeling. Why? Because of the long, sustained notes. Followed by notes that are as long as the silences between them. The music reaches a low point from which Beethoven builds up the music all over again and finally affirms the key. You might call this the road from chaos to order, or from desolation to happiness. I'm not going to linger on these poetic descriptions, because the music means different things to different people. But one thing is clear. If you have a sense of belonging, a feeling of home, harmonically speaking—and if you're able to establish that as a composer, and establish it as a musician—then you will always get this feeling of being in no-man's-land, of being displaced yet always finding a way home.

This is what Wagner cultivated, and what other composers reproached him for. Wagner's intuition for acoustics changed how we hear music, and how we hear is always relational, or pitched towards the sense of expectation. Barenboim credits Wagner as being the first with such a sense, though he adds a caveat for “Berlioz, and in a certain way Liszt, although Liszt was more limited to the piano.” He continues speaking to Edward Said:

By acoustics I mean the presence of sound in a room, the concept of time and space. Wagner really developed that concept musically. Which means that a lot of his criticism of performances of his own time, conducted by Mendelssohn and other people, was directed at what he considered a very superficial kind of interpretation of music, namely, one that took no risks, that didn't go to the abyss, that tried to find a golden path without having the extremes. Of course, this kind of performance leads to superficiality. This also affected the speed at which the music was performed, because if the content was poor, the speed has to be greater.

Therefore Wagner complains bitterly about Mendelssohn's tempi. How did he propose to fight that superficiality? In two ways. One, by developing the idea of a certain necessary flexibility of tempo, of certain imperceptible changes within the classical movements.

Here, Barenboim is talking about how Wagner saw Beethoven rather than how he conceived of his own music. But this idea of flexibility of tempo, for Wagner, put more emphasis on performance and affect. "Every sequence—every paragraph if you want to speak in literary terms—had its own melos and therefore required an imperceptible change of speed in order to be able to express the inherent content of that paragraph," Barenboim said. To quote him at length:

What Wagner really maintains is that unless you have the ability to guide the music in this way, you are not able to express all that is in it, and therefore you remain on the surface. He was diametrically opposed to a metronomic way of interpreting music. He had this idea of Zeit und Raum, time and space. Obviously tempo is not an independent factor: in order to sustain a slower tempo, which Wagner considered necessary for certain movements (not everything had to be slow, only certain movements and certain passages), he considered it an absolute necessity to slow down imperceptibly the second subject in a classical symphony where the first subject was dramatic—masculine, or whatever you want to call it—and the second was a contrast to that. But in order to make the slightly slower speed not only workable, but to allow it to express the content of the paragraph and to keep it within the context of the movement, there has to be, of course, some tonal compensation, and this is how he came to the concept of the continuity of sound: that sound tends to go to silence, unless it is sustained. From this came the whole concept not only of the color of sound—which is what so many people talk about today and which has led to (to my mindi superficial ideas about the "international sound of orchestras" — but of the weight of sound. And Wagner was more interested in the weight of the sound.

The weight of sound v. the weight of the sound.

*

the name Osip comes toward you, you tell him what he already knows,

he takes it, he takes it off you with hands,

you detach his arms from their shoulder, the right, the left

— Paul Celan (see translation as dismemberment), as translated by Pierre Joris

the name, the name, the hand, the hand,

there, take them as your pledge,

he takes that too, and you have

again what's yours, what was his

— Celan from same poem, I think he was translating Mandelstam at the time, and in dialogue with him