I have been one acquainted with the spatula,

the slotted, scuffed, Teflon-coated spatula

that lifts a solitary hamburger from pan to plate,

acquainted with the vibrator known as the Pocket Rocket

and the dildo that goes by Tex,

and I have gone out, a drunken bitch,

in order to ruin

what love I was given,

— Kim Addonizio, “The First Line Is the Deepest”

This morning Caserio Santo, the assassin of President Carnot, was executed; the papers are full of phrases such as: Santo died like a coward. But surely he didn't; it is true that he trembled so that he could scarcely walk to the scaffold, and his last words were spoken in so weak a voice as hardly to be audible, but these words were the assertion of his faith: Vive l'Anarchie. He was faithful to his principles to the last; his mind was as free from cowardice and as firm as when he struck the blow which he knew must be expiated by his own death. That he trembled and could scarcely speak are the signs of the physical terror of death, which the bravest may feel, but that he spoke the words he did shows strange courage. The flesh was weak, but the spirit unconquerable.

— W. Somerset Maugham, A Writer’s Notebook

Speaking of the mythos of “strange courage” and “unconquerable spirits,” I return again to the iconography of Saint Sebastian, this time with an eye to El Greco’s depictions, or the three oil paintings attributed to him— the first of which remains my favorite.

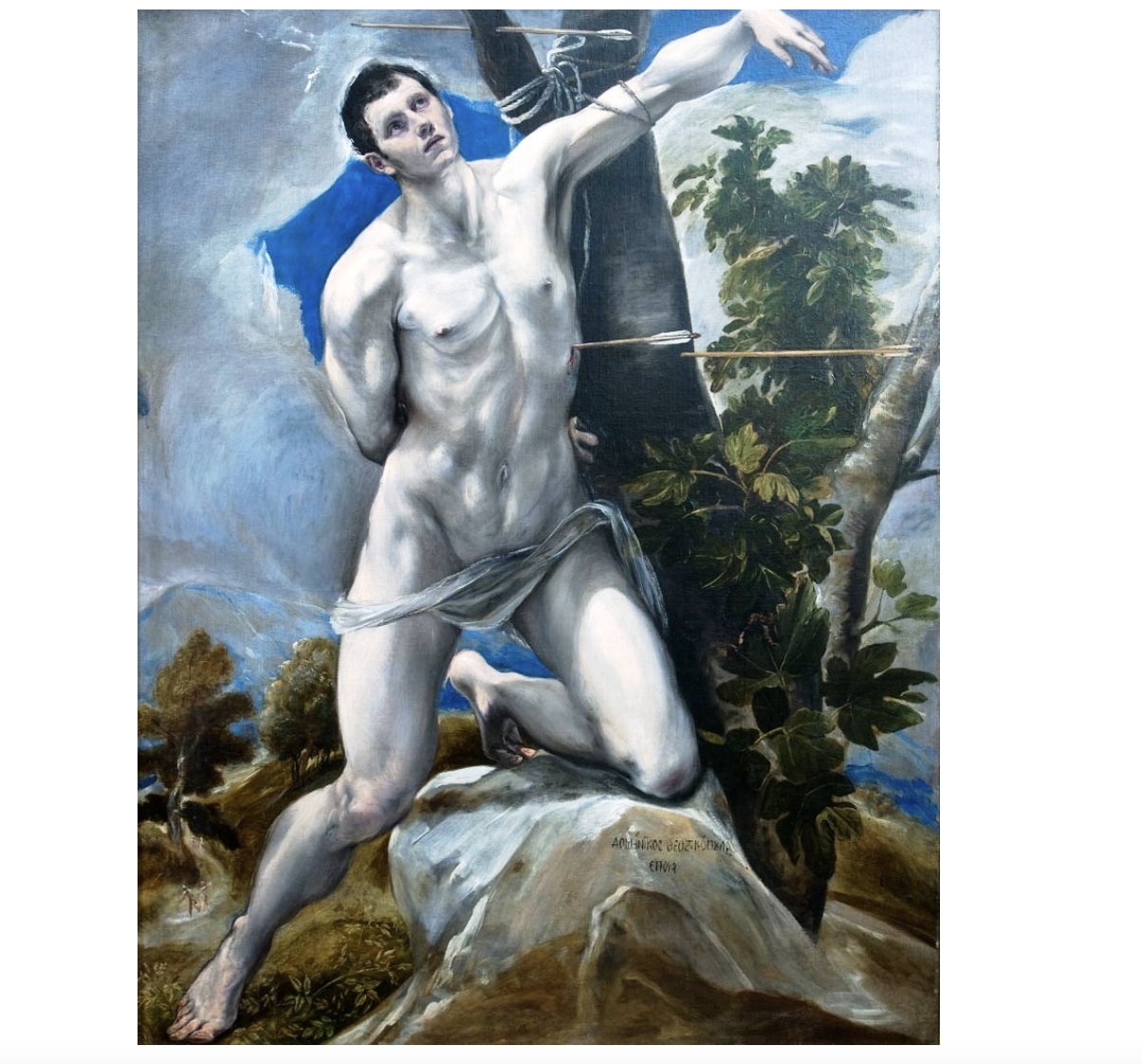

1. El Greco, Saint Sebastian, or Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. 1576-79

Oil on canvas, a wash of blues. Unique for the way the clouds part to frame Sebastian’s head with that bright cerulean blue sky. Both the tree and the torso of Sebastian are punctured by arrows, and there is something alarming or eerie about the arrow puncturing the tree’s upper limb. One can almost feel it. Some think El Greco used Titian’s work as a model, since Sebastian is depicted similarly hanging from bonds which tie his elbows to a tree, and El Greco's decision to put his signature on the stone under the saint's left knee resembles Titian’s sign his piece on the stone under his Sebastian's foot. The signature brings the artist into the composition here; it isn’t peripheral.

*

“Dostoevsky reminds me of El Greco, and if El Greco seems the greater artist it is perhaps only because the time at which he lived and his environment were more favorable to the full flowering of the peculiar genius which was common to both. Both had the same faculty for making the unseen visible; both had the same violence of emotion, the same passion. Both give the effect of having walked in unknown ways of the spirit in countries where men do not breathe the air of common day.Both are tortured by the desire to express some tremendous secret, which they divine with some sense other than our five senses and which they struggle in vain to convey by use of them. Both are in anguish as they try to remember a dream which it imports tremendously for them to remember and yet which lingers always just at the rim of consciousness so that they cannot reach it. With Dostoevsky too the persons who people his vast canvases are more than life-size, and they too express themselves with strange and beautiful gestures which seem pregnant of a meaning which constantly escapes you. Both are masters of that great art, the art of significant gesture. Leonardo da Vinci, who knew somewhat of the matter, vowed it was the portrait-painter's greatest gift.”

— W. Someset Maugham in his notebook from 1917, when he went on “a secret mission to Russia”

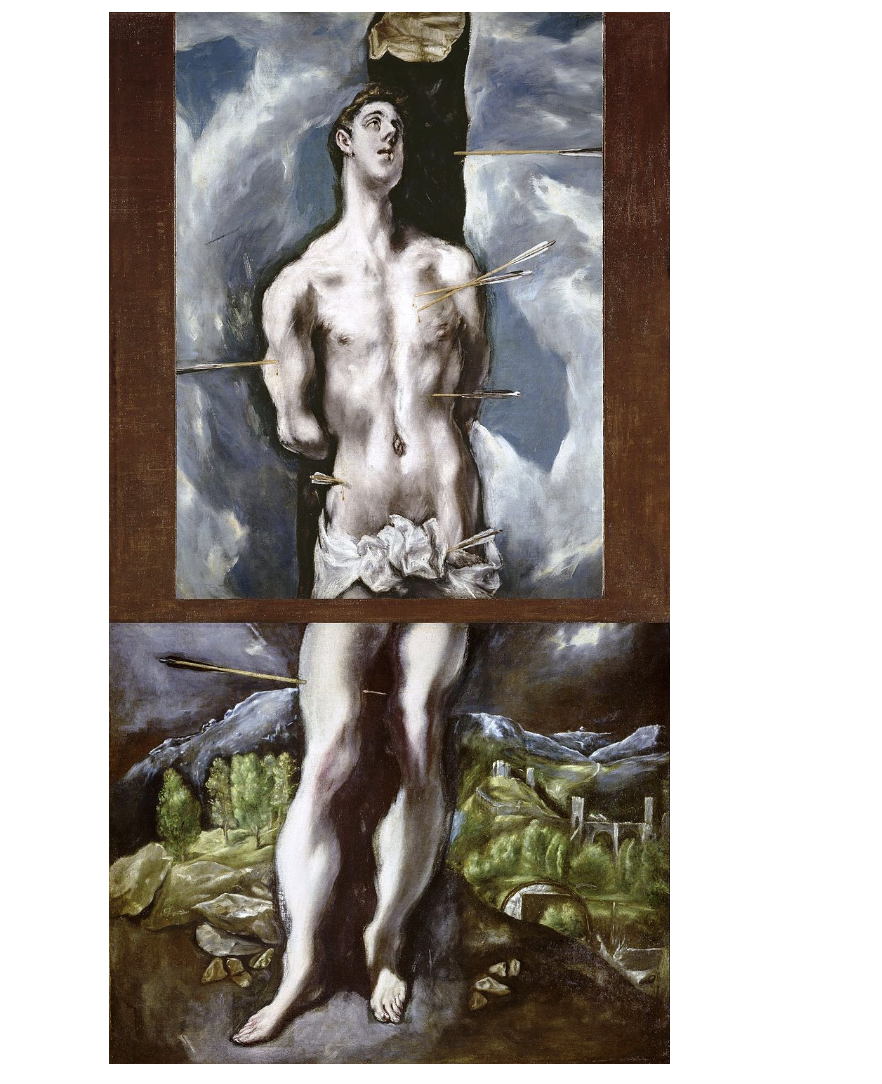

2. El Greco, Saint Sebastian c.1600-1605 or c.1610-1614

The second Saint Sebastian bears a much stronger resemblance to the final portrait in El Greco’s series— and the date reflects this confusion, naming it as c.1600-1605 (according to Tiziana Frati’s catalogue raisonnés) or c.1610-1614 (according to Harold Wethey’s catalogue raisonnés). Historians surmise that it was originally a rectangular full-length portrait that was cut down into an oval at an unknown date.

A legal battle over the ownership of an El Greco painting withdrawn from a Christie’s New York auction in February is advancing, as Romania has secured a “long-term hold” on the work, Saint Sebastian (ca. 1610–14), claiming it is part of its national collection. Court documents now reveal the painting’s owner is Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, who acquired it in 2010 from dealer Yves Bouvier through his offshore company, Accent Delight. The El Greco painting will remain at Christie’s until the dispute is resolved by legal authorities. It had been estimated to sell for between $7 million and $9 million.

— The Art Newspaper, June 2025

In 1898, Romania’s King Carol I acquired the painting and bequeathed it to the Romanian royal collection. El Greco’s oval-cut Sebastian stayed in Romania until 1976, when the art-dealing firm Wildenstein & Company had ownership of the painting transferred to them. In early 2025, the Romanian government claimed that the El Greco had been taken from Romania illegally in 1947 by Carol's descendent, Mihai, who also happened to be the last king of Romania and who fled his homeland after Petre Groza and Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej forced him to sign a pre-written abdication letter on December 30, 1947.

*

”Melville. A tall man, with a saturnine countenance, long, dark, curling hair, turning gray, and strongly marked features. He is going to Australia to produce American farces and musical comedies. He has traveled all over the world and talks enthusiastically of Ceylon and Tahiti. He is very affable when spoken to, but naturally silent. He sits reading French novels all day long.”

— W. Somerset Maugham in his 1915 notebook

3. El Greco, Saint Sebastian. 1610-1614

Oil on canvas. The final of El Greco’s three portraits of the saint. It survives in two large fragments, both of which are in the Prado Museum; the top half was donated by the Countess of Mora y Aragón in 1959 and the lower half was acquired in 1987. Frankly, I hate it. The elongated neck and throat of Sebastian plays into the grotesque, but doesn’t play hard enough. The background includes a view of the town of Toledo that places Sebastian in a context that has nothing to do with him, possibly at the request of his patron or to create an artificial association between the saint and the city.

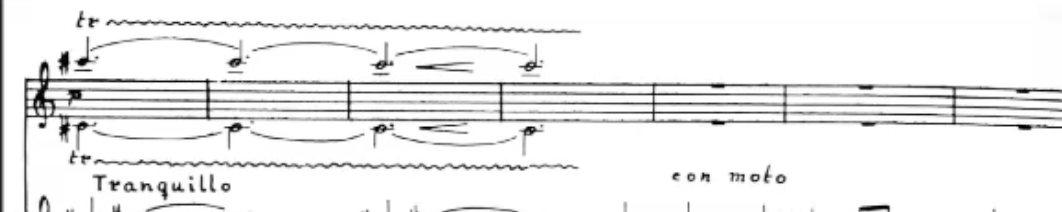

From Atterberg’s score for Suite No. 3

There are times when I look over the various parts of my character with perplexity. I recognize that I am made up of several persons and that the person which at the moment has the upper hand will inevitably give place to another. But which is the real me? All of them or none?

— W. Somerset Maugham, early notebooks

*

Kurt Atterberg, Suite No. 3 for Violin, Viola & String Orchestra, Op. 19, No. 1 (1917)

W. Somerset Maugham, A Writer’s Notebook (1915)