“Right now, in the heat of the moment, with everything in a fever—my hands and my head and the weather—I still have not sensed it fully. But I know myself, I know what awaits me! I’ll break my neck looking back: at you, at your world, at our world.”

— Marina Tsvetaeva to Anna Tesková, June 7, 1939, five days before Tsvetaeva's final departure from Paris

“Writing cannot bring anything back.”

— Judith Schalansky, An Inventory of Losses

1. “MY PUSHKIN”

A. Naumov, Alexander Pushkin's Duel with Georges d'Anthes (1884)

And ever since then, ever since when Pushkin was killed right in front of me, in Naumov’s picture, daily, hourly, over and over, right through my earliest years, my childhood, my youth, I have divided the world into the poet and all the others, and I have chosen the poet, I have chosen to defend the poet against all the rest, however this ‘all the rest’ is dressed and whatever it hap- pens to be called.

But even before Naumov’s duel, because every memory has its pre-memory, its ancestor-memory, its great-great-great memory, just like a fire escape ladder which you climb down, never knowing whether there will be another rung – and there always is – or the sudden night sky, opening up ever higher and more distant stars to you – but before Naumov’s The Duel there was a different Pushkin, a Pushkin, when I didn’t even know that Pushkin was Pushkin. Pushkin not as a memory, but as a state of being, Pushkin forever and forever-forth, before Naumov’s Duel there was a morning light and rising out of it, and disappearing into it, was a figure, cutting with its shoulders through the light as a swimmer cuts through a river, a black figure, higher than everyone else, and blacker than everyone else, with his head bowed, and a hat in his hand.

— Marina Tsvetaeva, “My Pushkin”

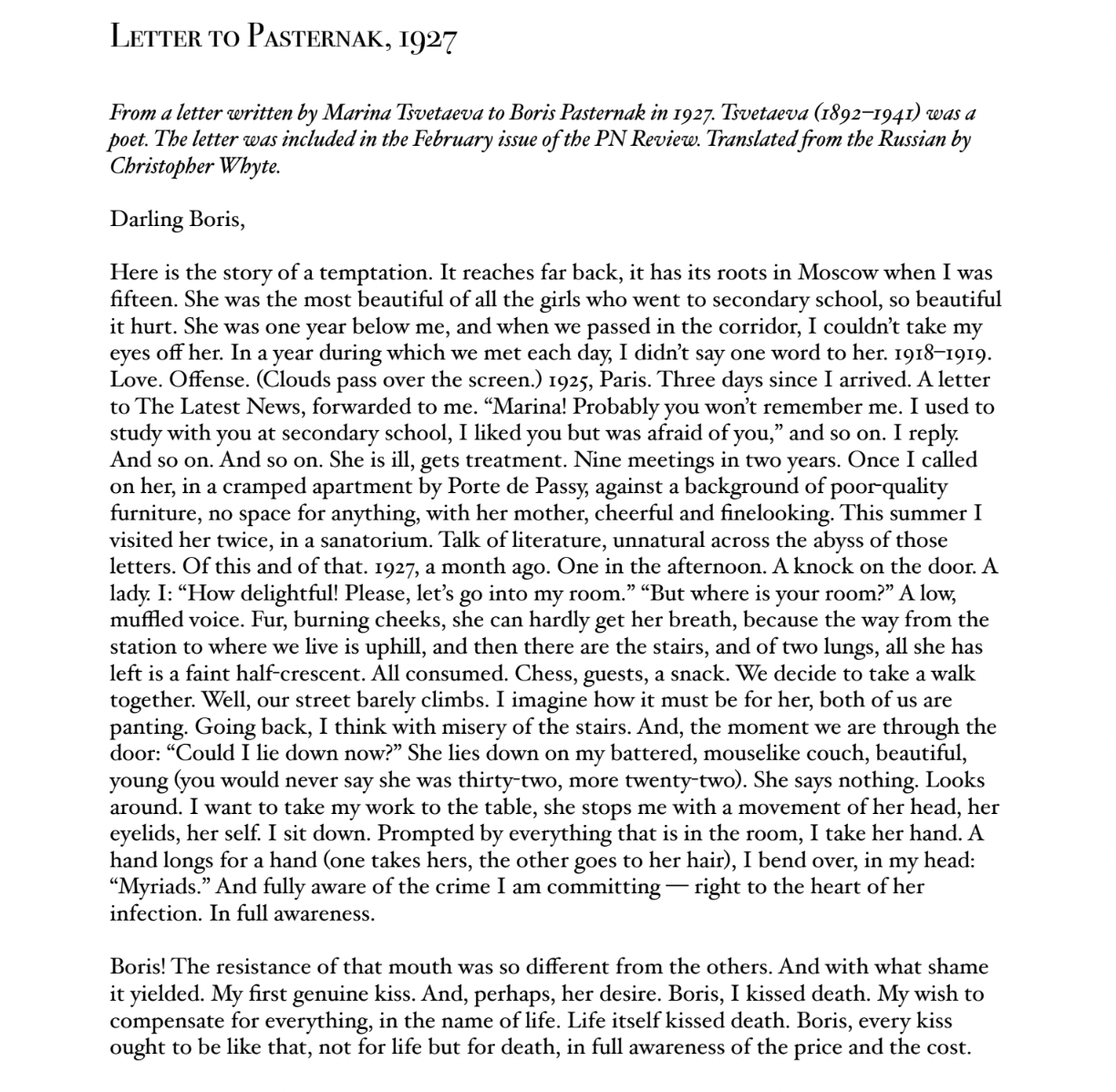

2. THE EPISTOLARY “I”

"Writing cannot bring anything back," warns Judith Schalansky. Writing cannot recreate what is absent, but it can create the conditions for an experience of what is missing. It can make space for the possibility. In letters, we see this often— we feel the way in which the interlocutor stands in for a hope that is not simply local but rather rooted in a form of address, an opening-unto the world. Nowhere is this more apparent perhaps than in the correspondence between Boris Pasternak and Marina Tsvateva.

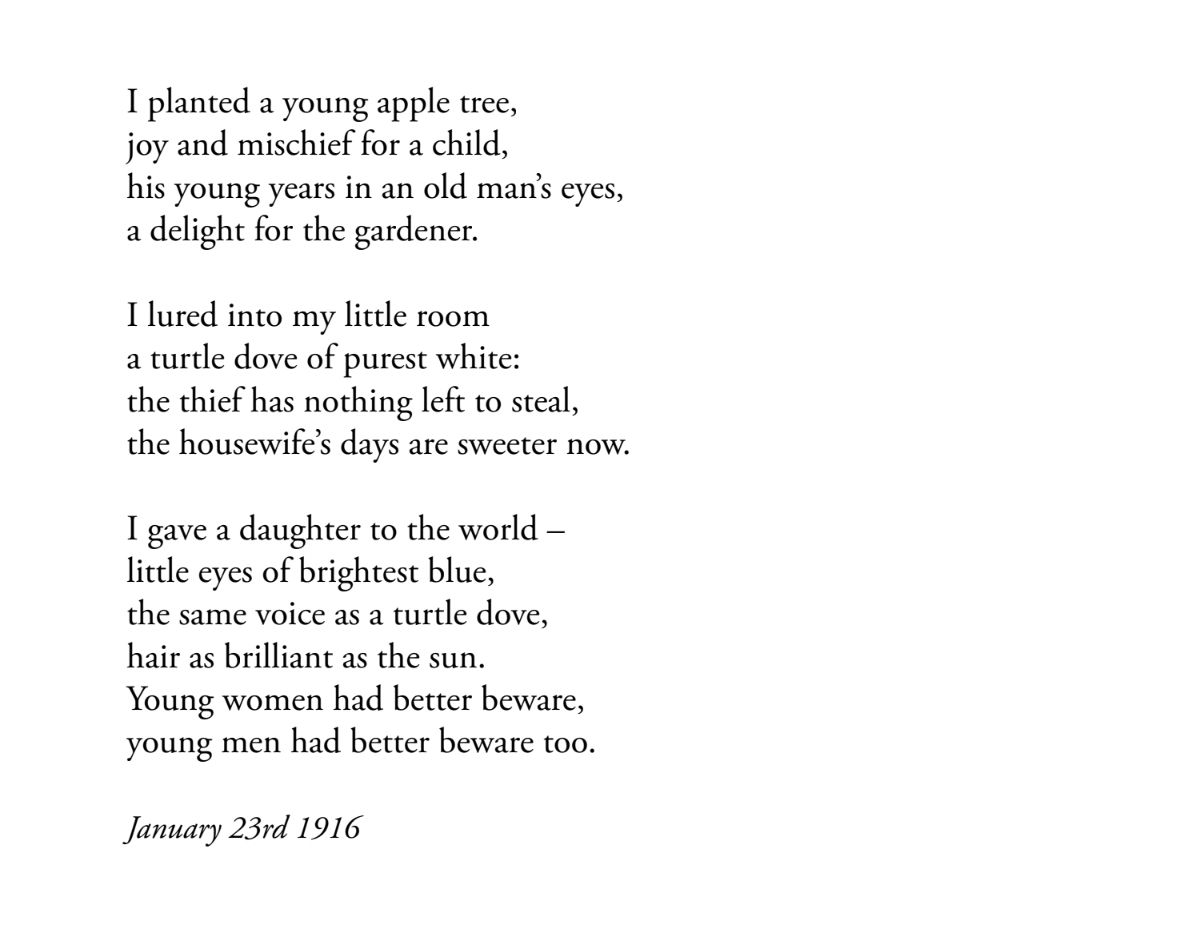

These descriptions and evocations move from Tsvetaeva’s letters to her poems, back and forth, back and forth, she reworks them until she feels them coming to fruit, or fruition. Here is one of her poems published in Milestones, as translated by Christopher Whyte.

The poem marks a date— and the incident described in it could have been written in a letter or a diary. It is a personal event, memorialized, made legible to a public. The turtle dove is the metaphor she is working… trying to touch on the soft coo of the daughter, the infant, this new relationship that defines her being in the world as mother.

3. THE SPEAKER AS SOMETHING YOU DREAMED

The poet Simonides of Caes was the single survivor of the Thessaly house party in 5th century BC. According to legend, Simonides used his memory to relive the seating arrangement, thus identifying the buried dead beneath the rubble. Ancient Greeks took dreams as oracle, pre-visioning what would come, removing "the terror of the unexpected from the future," to quote Judith Schalansky. But dreams don't prepare us for the wind shear of facts.

Attention to dreams prepares us for the fragmentary, the disconnected, the fantastic, the immaterial. But dreams are not always unconscious— we dream of a world in which we can be whole, or be wholly ourselves without violence and terror. We dream of a world in which our dreams matter, our dreams are material to the conditions of living. In this sense, perfect memory can be a handicap that prevents us from re-membering, or piecing the past back together, by making it impossible to choose among pieces. Like the rich, the house of perfect memory is so big that one feels trapped, one becomes claustrophobic, in the ordinary, small houses of others. The richness of one's house ruins the ordinary by estranging us from inhabiting it. One can't abide in the chaos of unpruned synapses. So we pare things down; we reduce and highlight; we narrate over the gaps.

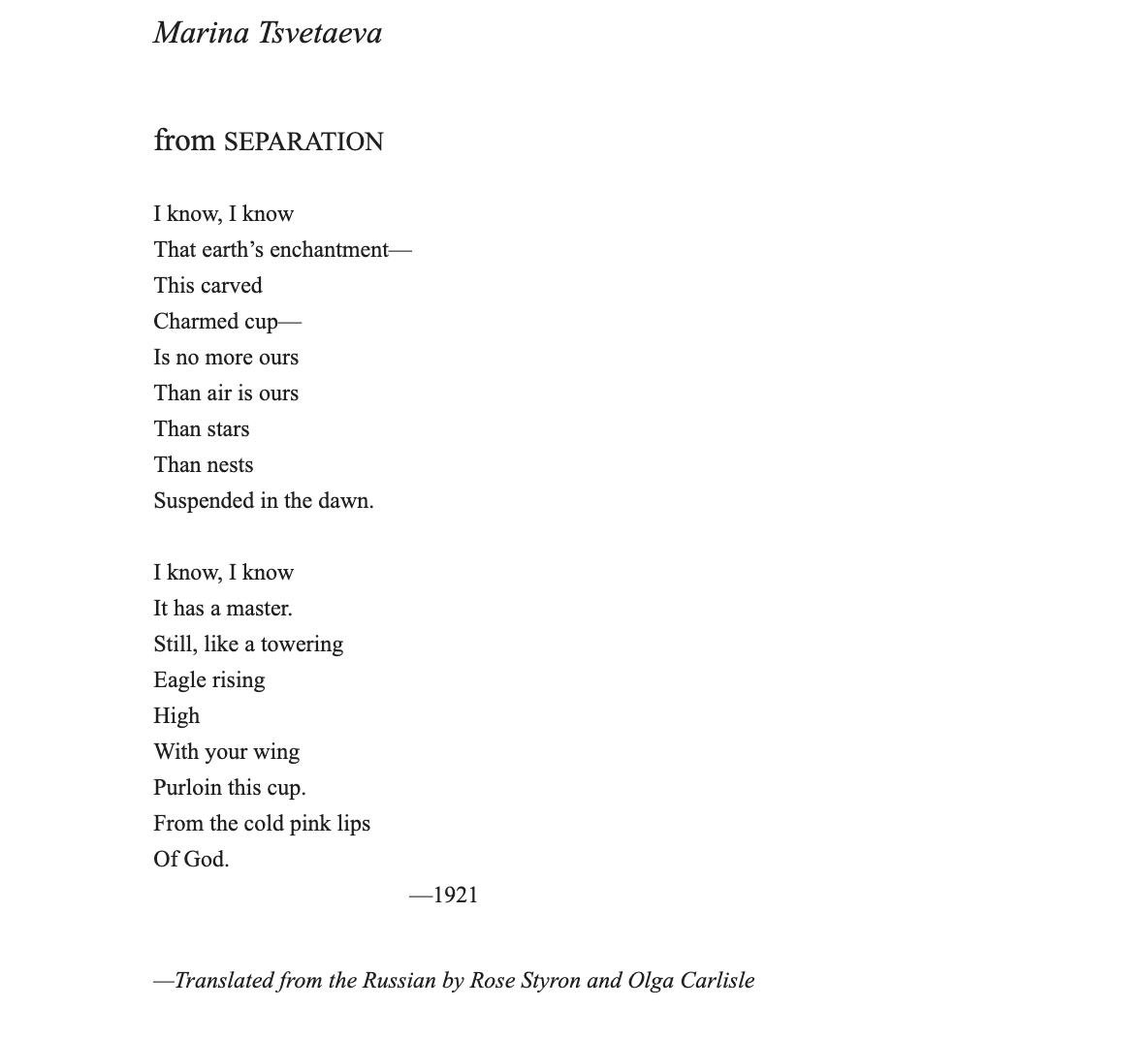

But poetry, perhaps more than any other mode, calls our attention to the gaps. The field and lineation makes those gaps visible and tangible. And this is the visionary, the radically-threatening possibility of the poem. We mourn when touched by the vestige of an absence, when startled by the echo of a correspondence. There is something missing. Everything that exists is a ruin waiting to happen once the curator disappears.

Two more by Tsvetaeva, as translated by Willis Barnstone and Edward J. Brown:

ARS POETICA

I was born with a song in my tongue—but would

not waste it for a phony chasuble or hood.

I dream—not in bed—but in full day, awake,

and can’t live like you with chitchat of a snake.

I come from you, lyre, my lyre, and my voice

and chitchat are your swanlike curve and hiss.

I’m an ally of the laurel, the wind and dawn,

and would rather be happy: I am no nun,

and have a friend who is blond—maybe a rat,

but I stick with him when everything is bad.

I come from you, lyre, my lyre, and my voice

and chitchat are your swanlike curve and hiss.

They say to be a woman is a heavy fate.

I wouldn’t know. I never take my weight.

I freely give—but never sell my goods to you,

and now that my fingernails are turning blue

my death rattle and eagle scream and wheeze,

lyre, my lyre, are your swanlike curve and hiss.

IN MY IMMENSE CITY

In my immense city it is night.

I walk from the house mued tight

in sleep where they say daughter? wife?

but I remember one thing—the night.

Before me a sweeping July wind

and in some window a hint of song.

Tonight the wind will blow till dawn,

blow through my breasts. They are very thin.

A black poplar, and in the window

a lightbulb; chiming on the tower and

a flower in my hand. Shadow

and steps follow no one. There is no

me. Lights! like strings of gold beads.

The taste of a small nocturnal leaf.

Free me from the mouth of day. Friends, please,

try to understand: I am your dream.

The non sequiturs of this post are simply intended to provide additional material to explore for those in the “Flaschenpost” in the Present: Sending Poems Across Language and Time workshop. Obviously, I could ramble on forever since this topic is near and dear to my heart, but instead I will bind my tongue briefly and leave you with the following:

“My Pushkin” by Marina Tsvetaeva (translated by Sasha Dugdale)

”Ars Poetica” and “In My Immense City” (translated by Barnstone and Brown)

An Inventory of Losses by Judith Schalansky (translated by Jackie Smith)

”Limerance” by Yves Tumor

”Je suis le vent” by Working for a Nuclear Free City