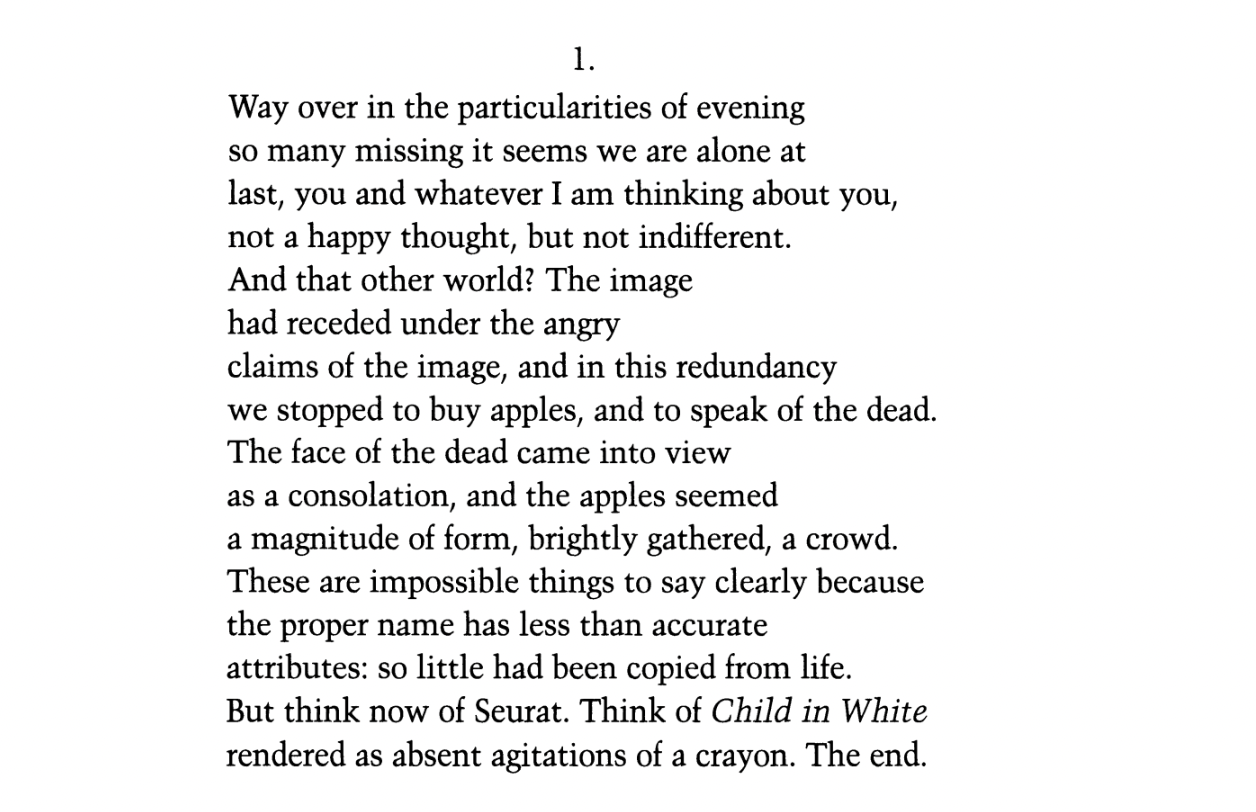

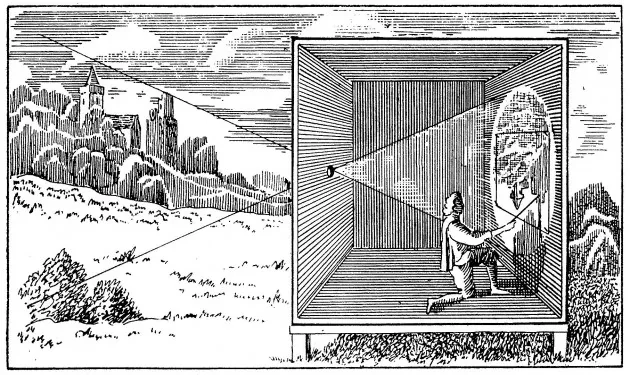

lens 1

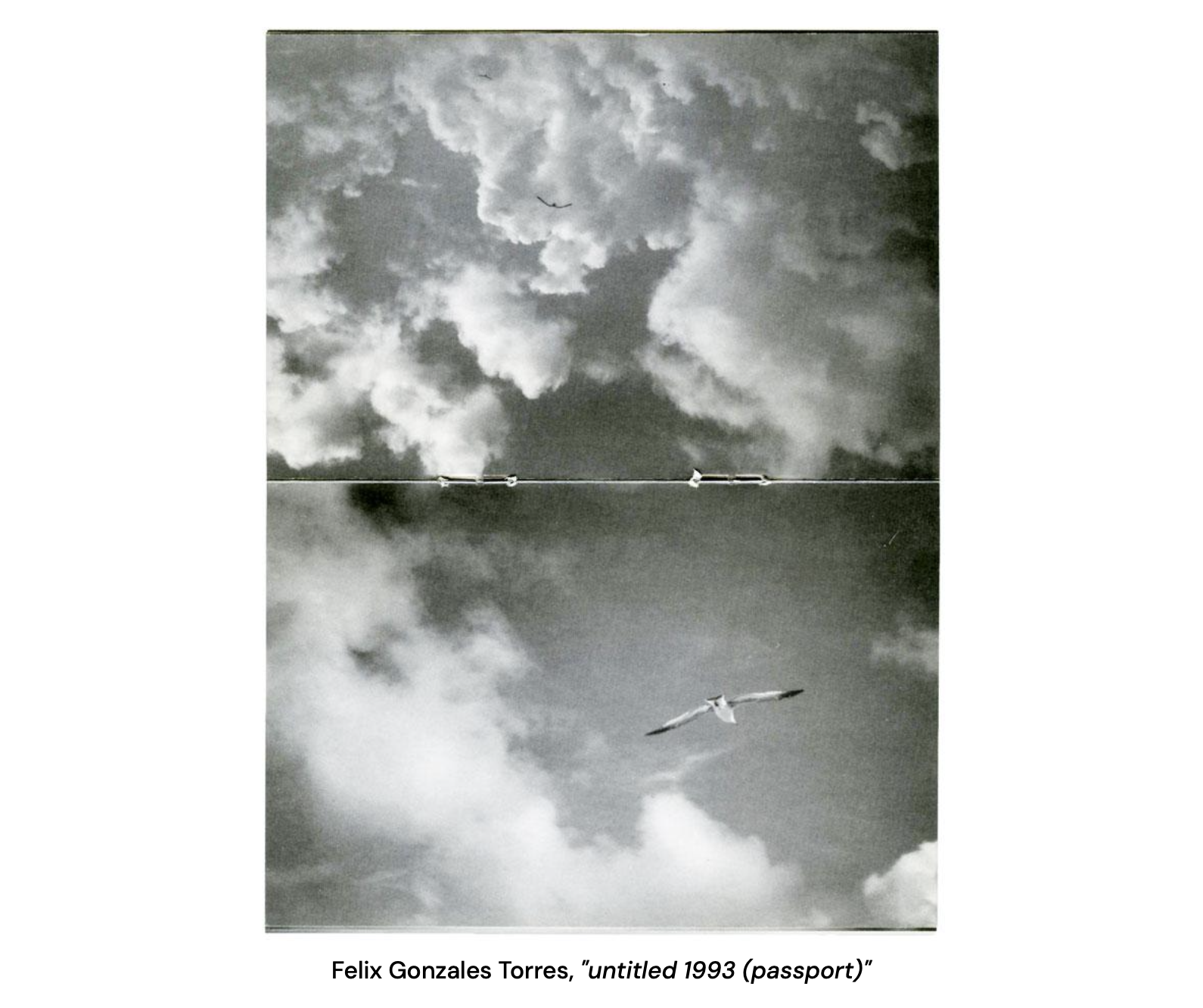

— the incredible lightness of being that Novalis experienced while in Her presence negated the despair that time unfolds on an Us. The ‘solution’ to the existential crisis lies in the reflection. Reflecting allows us to escape our finiteness by encountering the “absolute joy” that remains “eternal – outside all time.” We turn “displeasure into joy, and with it time into eternity,” Novalis whispered to his Reflection.

lens 2

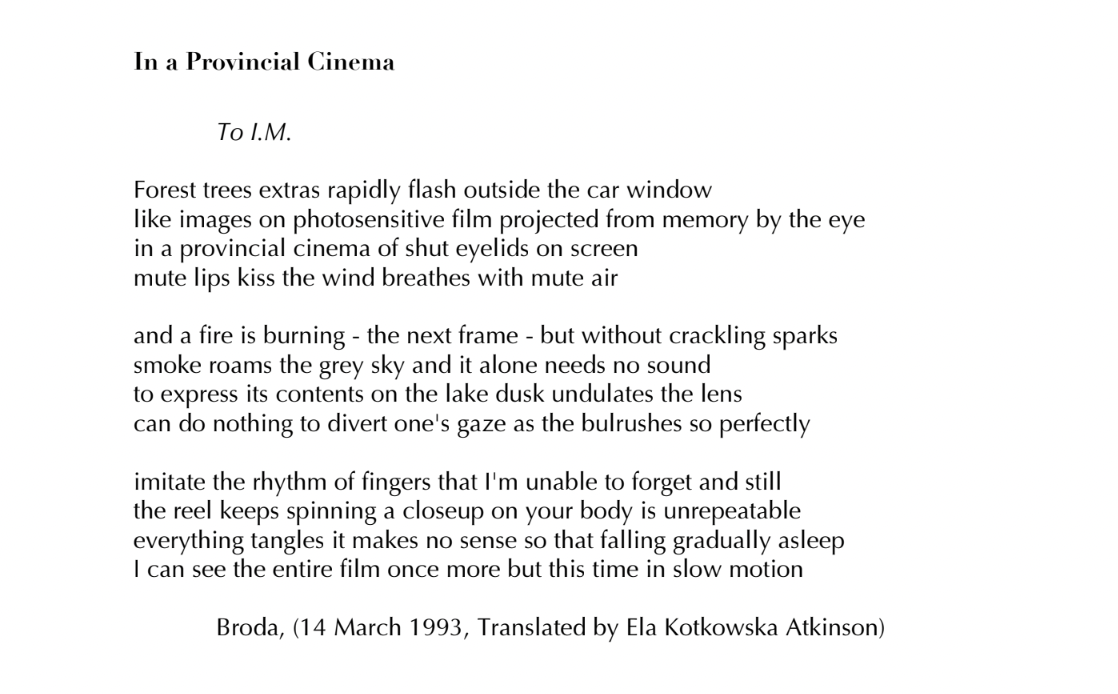

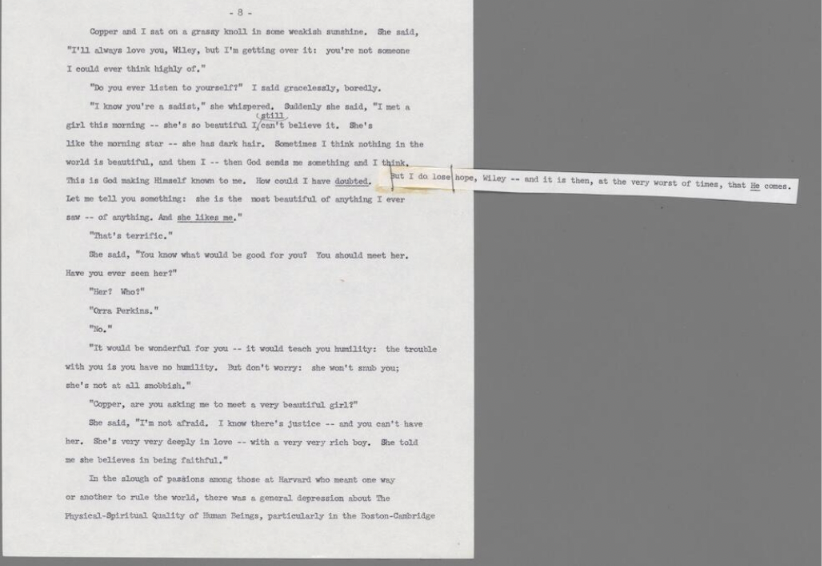

When Constantin Constantius returns to Berlin in order to replay or reexperience his time in the former lodges next to Gendarmenmarkt, he is mining for repetition. And this repetition – the replay of fond images — is the technical marvel accomplished by the family movie, or even the cinema film watched with a first love. There is a loop into Krapp’s Last Tape…though what Beckett reveals is the subject’s failure to recognize the prior selves. To recognize is a way of claiming: it is recognition that precedes both recollection and repetition. (K avoids this, I think.)

lens 3

It is strange to lose the only thing I’ve never lost before— not since the age of 18, when I wore a bob. It is eerie to watch my hair fall out in clumps without explanation. The discomfort of humans in white coats allows me to abandon the confused woman and step forward to reassure the professionals: “Surely it will be fine.” “Just do what you know.” “How will this medication affect my insomnia?” “I understand that diagnosis is a betting game.” “I know you are doing your best.” “I know you regret how the prescription from four weeks prior only caused more hair to fall from my head.” “I’ll be damned if the sun isn’t extraordinary, even though it visits us less. . .”

lens 4

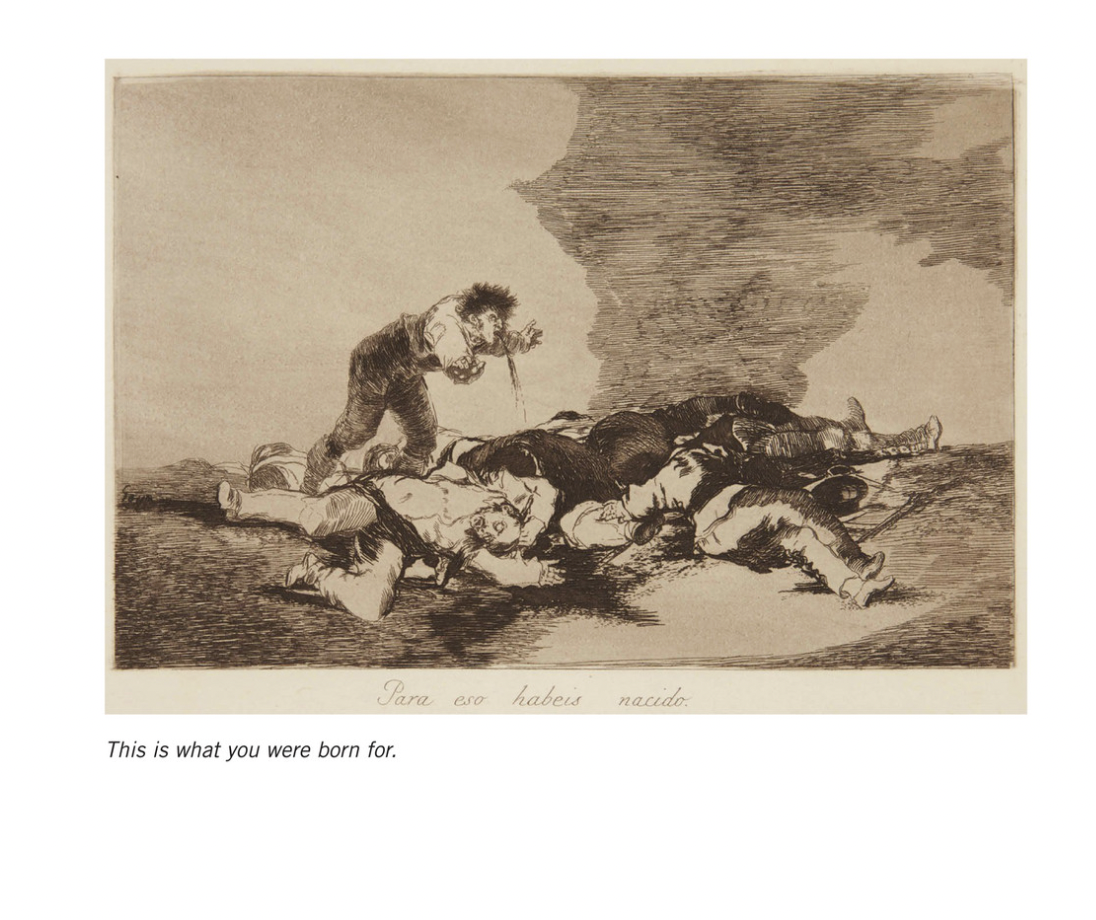

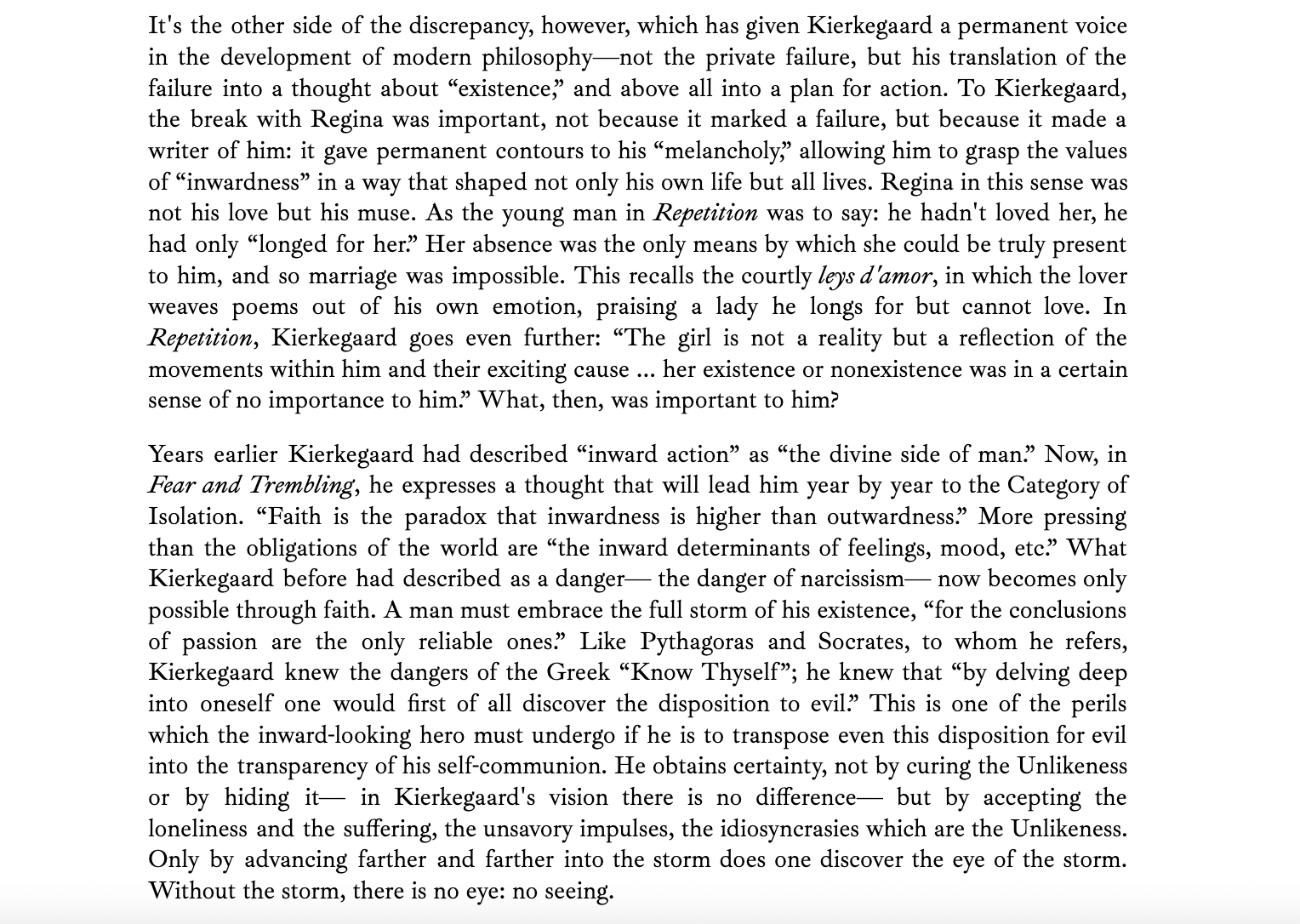

In his journals from the early 1850’s, K meditates on the forgiveness of sin in relation to how we perceive life’s accidents. He argues for an “altered view” that what God shows us isn’t the “punishment” but rather mercy, so no bad things are an “expression of God’s wrath” but rather a thing of suffering, to be born with God, who knows suffering through Christ. And now, K takes this further, saying that “Punishment is not the pain in itself” since the same identical pain or suffering happens to others as “mere accident.” Instead, “punishment is the idea that this particular suffering is punishment. When this idea is removed, so too, really, is the punishment.”

Socrates never sought to prove the immortality of the soul. Instead, he simply lived as if immortality were a fact about the cosmos. In this sense, says K, if there is no such thing as immortality — if the as if that governed his choices proves to be false — “I still do not regret my choice; for this is the only thing that concerns me.” The choice. The decision. The commitment. A little Pascalian wager with his back against the wall.

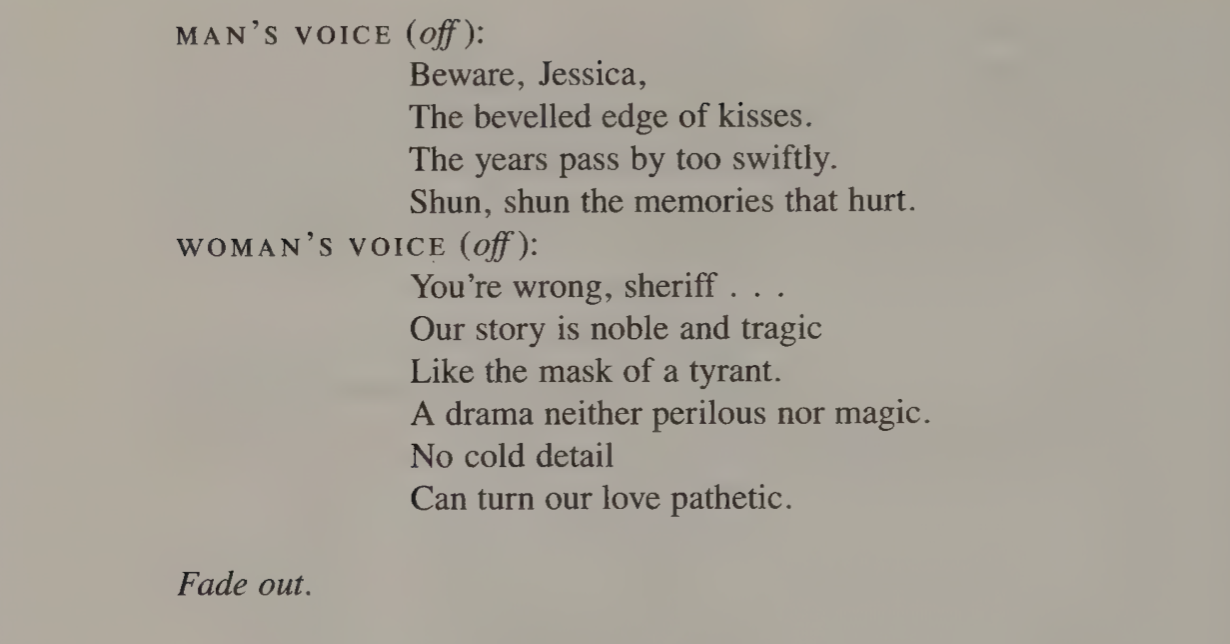

lens 5

HE: What drew you to K?

ME: I recognized my own fear of commitment in him.

HE: Oh? But he is deeply committed!

ME: Committed to the thing he can neither see nor prove. Committed to uncertainty.

HE: False. Kierkegaard is committed to certainty. He knows what he knows by faith.

ME: Maybe. But who knows what the conditions of such knowing might be?

HE: You know what you are . . . or when someone says this, you think ‘a writer’.

ME: In our world, this breaks down into various categories, and each has its corresponding affect. I create texts, but what does that make me to you?

HE: A writer.

ME: Johannes de Silentio identifies as a ‘freelancer’ in Fear and Trembling.. . . I identify with K’s decision here, this choice to name the self as a freelancer in order to expand the field of thought. Don’t you think contemporary thought is drained by genre and brand?

HE: K calls himself ‘a kind of poet’ . . . in his journals, in his texts, in his discourses. Kierkegaard was a poet to himself.

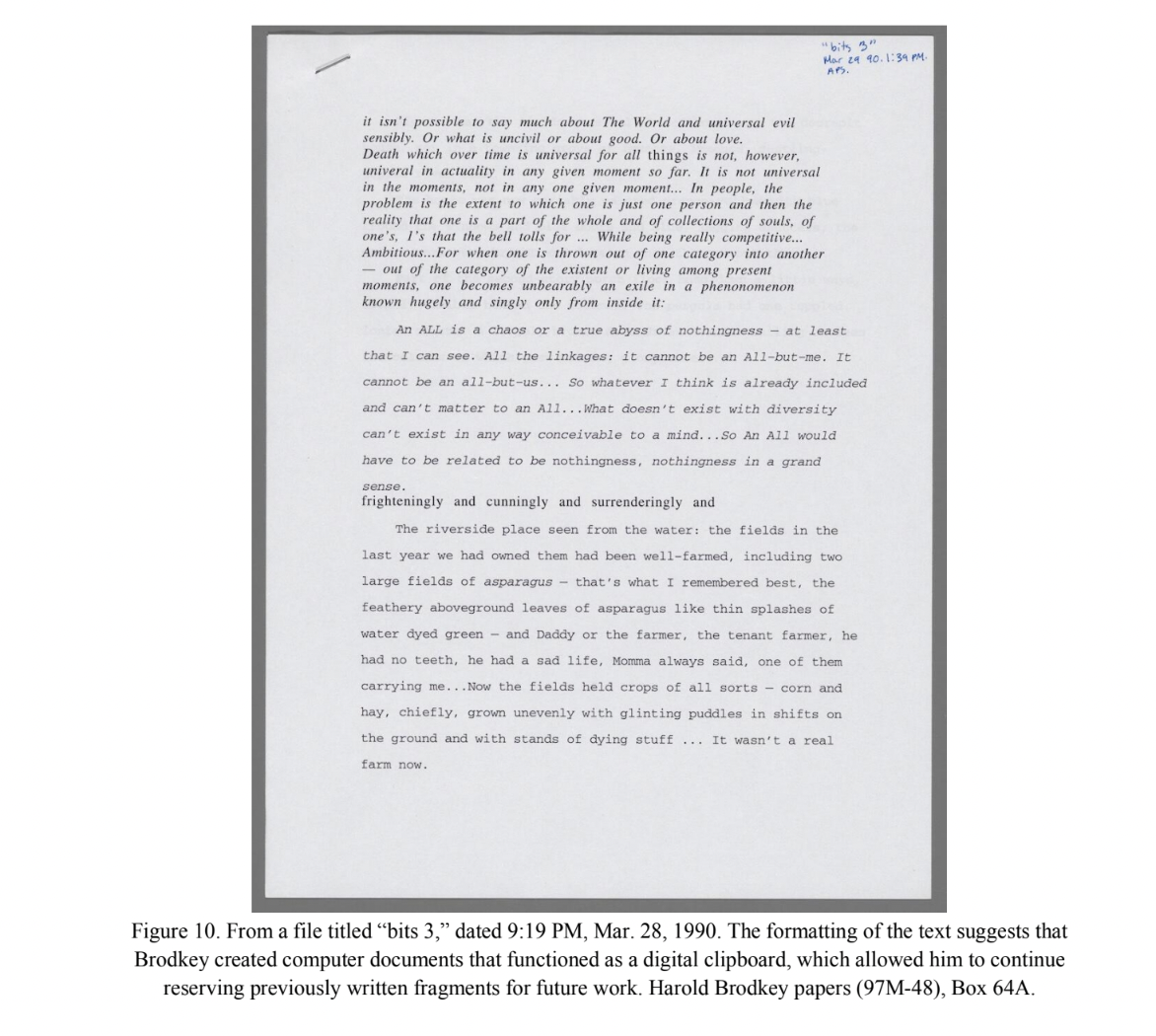

ME: I think many philosophers are poets are heart. But taking K at his word, his books refused the given boxes. Prefaces, Either/Or, Postscript: all situate themselves uncomfortably in relation to communicative function because destructive of the text. The countergenre. A creature that offers itself apophatically by insisting on what it is not. He calls Fear and Trembling “a dialectical lyric” but it is also a mix of exegesis, fabulism, social commentary, farce, and dialectical study. He says his Prefaces are “like tuning a guitar, like talking with a child, like spitting out of the window” and I hear him say, look, anything can happen, and everything that does may be an accident. Postscript, the text titled after the P.S., which is the paratext that names itself as an addendum to the original. It tells us that it is a “postscript to crumbs of philosophy,” the son of its father text. The subtitle calls it a “mimic-pathetic– dialectic compilation–an existential contribution,” a promise to break the cherished molds of thought and classification. K. never tells us where to land. He guts the immediate life at stake: he lays the “I” on the line and then, in the final pages, reminds us to leave this useless text, to abandon its author and his musings just as he urged readers to leave Prefaces, that work of “a light-hearted-do-nothing.”

HE: (sighs) Losing your hair is most noticeable to you, A. Other people have to look closely to see what you’re hiding . . .

ME: I’d rather not. Look, I think what continues to provoke me in K is his obsession with finding a justified exception to the ethical.

HE: Sometimes I think take his subjectivity too far. He was going for an absolute, after all.

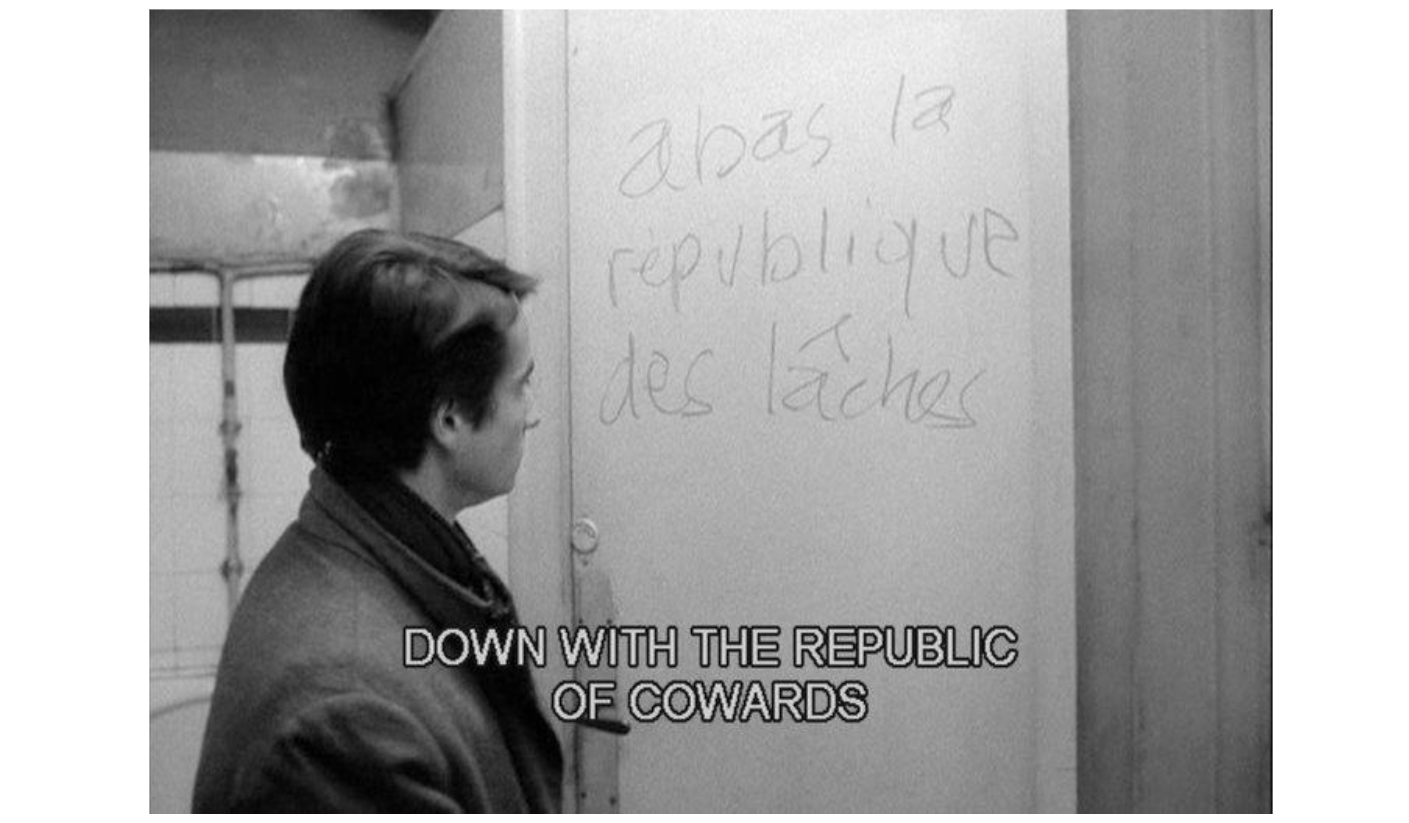

ME: But an absolute couldn’t absolve him of going for it. The self is disclosed in the reading, the labor of interpretation. There is no system that K wants to create. No temple or ideology. No comfortable institution that would enable the flourishing of police, or their cousins, the pastors.

HE: “I fear no one as I fear myself. Woe unto me in case I were to discover that there had been one deceitful word in my mouth, one single word whereby I had sought to persuade her —”

ME: Ha ha. God’s money in those worries. And maybe that is connected to what I was thinking, namely, how K refuses to tender the coin of the realm —

HE: And that coin is what?

ME: Respectability. Same game, different costumes.

HE: You mean flaying himself on the page in order to make sure that no part is left pure. I’m assuming. His refusal to offer an out.

ME: (nods) This refusal forces us into anxiety about our own choices–his dread becomes our own, the possible life, the one we could have lived if life and work was a thing we wanted to take seriously. Which is to say: existentially. As if eternity is at stake. One must choose.

I have the courage, I think, to doubt everything, to fight, I think, against everything. But the courage to recognize nothing, to possess nothing: that I lack. Most people complain that life is too prosaic, that life is not at all like those novels where lovers are lucky, as for me, I complain that life is not like those novels where one has hardened fathers to fight against, virgins' bedrooms to force open, convent walls to leap over. I have only the pale Figures of the night, stubborn and bloodless, to battle with, and I am the one who gives them life and being.

— Kierkegaard, in a journal entry several years before the Corsair affair