1

According to Javier Marias, when Henry James and Oscar Wilde met, James mentioned that he was missing London, at which point Wilde glanced at him with scorn and disgust. “Really! You care for places?,” Wilde huffed, and then added: “The world is my home!” From then on, James referred to Wilde as "an unclean beast" or "a fatuous fool" or "a tenth-rate cad." On the other hand, James’ “enthusiasm for Maupassant knew no bounds, again thanks to a single visit the French short-story writer had received him for lunch in the society of a lady who was not only naked, but wearing a mask.” It is a fact that Henry James died at the age of seventy-two, after a long illness. Before dying, in a fit of delirium, James dictated two letters to his “brother,” Joseph Bonaparte, urging him to accept the throne of Spain. At one point, James fell to the floor. Convinced that he was dying, James later said he heard a voice which was not his own in the room, and this voice said: “So it has come at last—the Distinguished Thing!”

2

The mythos of nationalism continues to create us. According to the U. S. Declaration of Independence, “the pursuit of Happiness” is one of the “inalienable rights” of man. Robert Calasso draws this to our attention in his book,The Unnameable, if only to point out that the exceptional. . . isn’t. This “magical word is also used in another text,” namely, the Catechism of a Revolutionary, drawn up by Sergey Nechayev. Article 22 reads of the Catechism reads: “The Society has no aim other than the complete liberation and happiness of the masses.”

Calasso argues that the secular world is looking for theories to satisfy the hole left by myth and meaning. He quotes Simone Weil’s essay on the Iliad: “The Gospel is the last and marvelous expression of Greek genius, just as the Iliad is its first.” If "Greece and the Gospels were two independent and non-discordant revelations,” this recognition was achieved by Weil’s metaphor of looking at a cubic box:

There is no viewpoint from which the box has the appearance of a cube: one always sees only a few sides, the corners do not seem right angles, the sides do not seem equal. No one has ever seen, no one will ever see a cube. For like reasons, no one has ever touched nor will ever touch a cube. If one moves around the box, an infinite variety of apparent forms is generated. None of these is the cubic form.

At the same time, we know that the cubic form constitutes the unity of all those changeable forms and “also their truth,” added Weil, who considered this to be a divine gift, so that “enclosed in our very sensibility is a revelation.” From this revelation one could move on to understand all the others. But, “for the secular world the cubic box does not exist," Calasso maintains. Bummer.

3

I walked Radu and thought about these two lines by McKenzie Wark, from her letter to Cybele — “Something is absent, offered to you, perchance. A hole made in a poem; a poem made whole by a cut.”

4

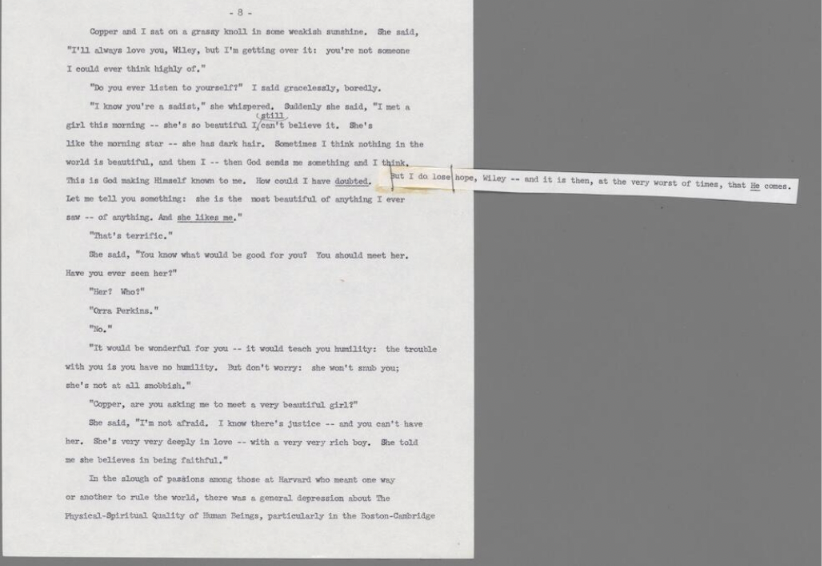

Rambling through my K-related notebooks again, where I found a passage from a book by Paul Zweig that I think speaks best for itself, without my clumsy paraphrasing and pithy summations. Zweig, then:

Paul Zweig, excerpted fromThe Heresy of Self-Love

5

Greil Marcus opens What Nails It with an essay titled after the father who died before he was born. “Greil Gerstley,” it reads, the “echo of an absent memory” evokes the man he never met, the soldier lost in a Pacific typhoon when his ship went down. This particular absence calls up the ghosts of all epics and shipwrecks, all odysseys and heroes and adventurers located beneath ad infinitum of “whatever comes” — and opening into the risk of oblivion. The waves and crests of Melville’s Moby Dick fill the background. In a later essay from the same book, Marcus mentions how powerfully that Melville’s novel affected him, and how reading it gives an ocean we cannot imagine, a context so betrothed to the unpredictable power of the natural elements that it can only be taken as an opposite of what we experience in our controlled, highly-commoditized lives.

6

Autumn 1940. Lisbon— according to Roberto Calasso— who quotes Arthur Koestler:

“And more suicides: Otto Pohl, Socialist veteran, Austrian ex-Consul in Moscow, ex-Editor of the Moskauer Rundschau, Walter Benjamin, author and critic, my neighbor in 10, rue Dombasle in Paris, fourth at our Saturday poker parties, and one of the most bizarre and witty persons I have known. Last time I had met him was in Marseilles, together with H., the day before my departure, and he had asked me: 'If anything goes wrong, have you got anything to take?' For in those days we all carried some 'stuff' in our pockets like conspirators in a penny dreadful; only reality was more dreadful. I had none, and he shared what he had with me, sixty-two tablets of a sedative, procured in Berlin during the week which followed the burning of the Reichstag. He did it reluctantly, for he did not know whether the thirty-one tablets left him would be enough. It was enough. A week after my departure he made his way over the Pyrenees to Spain, a man of fifty-five, with heart disease. At Port Bou, the Guardia Civil arrested him. He was told that next morning they would send him back to France. When they came to fetch him for the train, he was dead."

I keep staring at the letter “H.” and thinking about Marseilles.

7

Returning to Joanna Walsh’s My Life as a Godard Movie to think about this term she uses as a scaffold— motion parallax, meaning how the world moves with you when seen through the window of a train. The speaker loves riding the rails of her imaginings, running her nimble thoughts over an object and then creating a response. Like many writers, I recognize myself in that particular fissure.

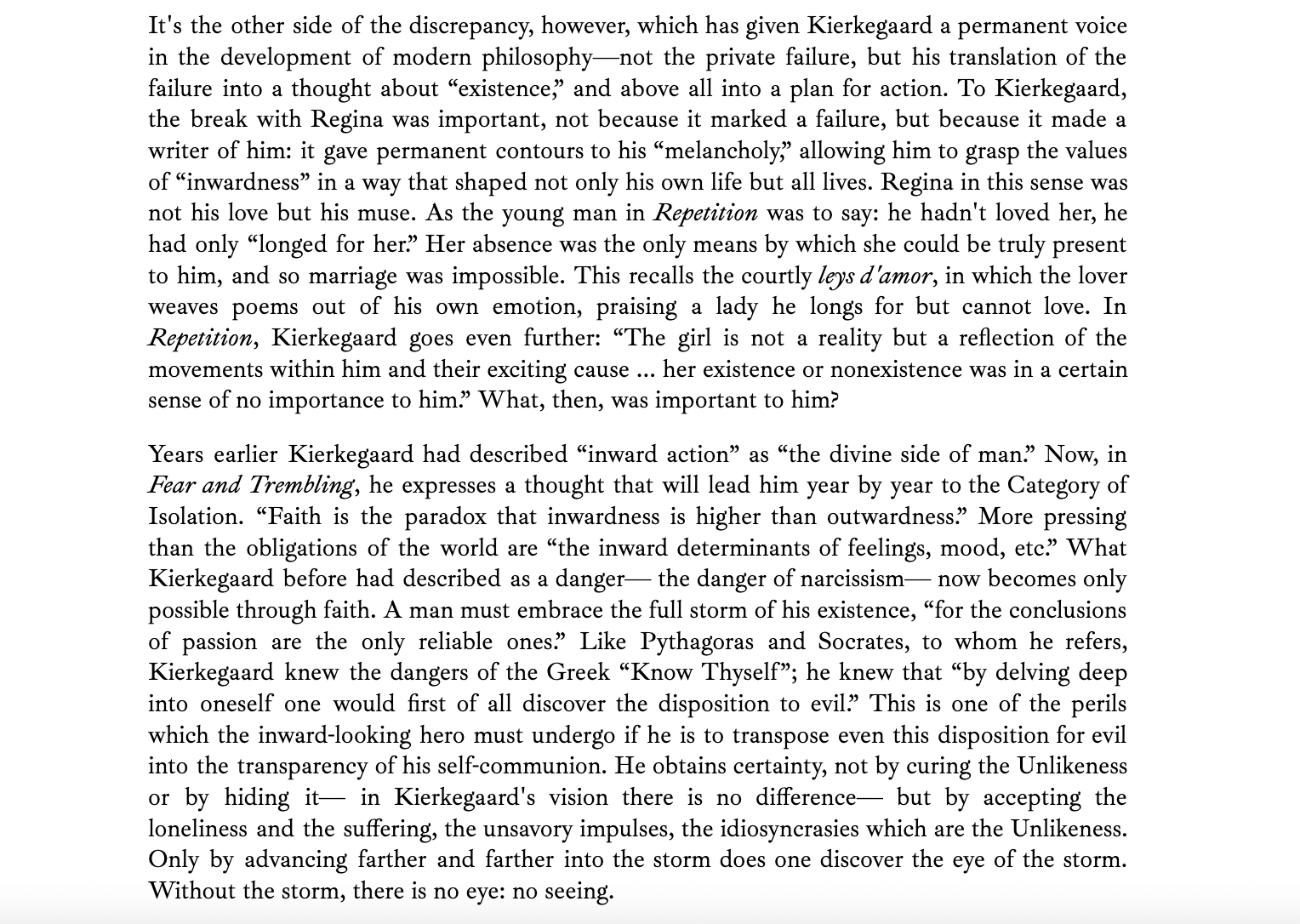

Walsh quotes Kierkegaard’s Repetition— “Does he love the girl or is she just another thing that moves him?” — but the quote could just as well apply to the speaker as to the Him of her book. And her book is about beauty, about the desiring gaze that defines the Godard's female protagonists. In turn, Godard builds his aesthetic from the appearances of his stunning heroines, Walsh sees "a resistance in Godard's women … in the way they look at Godard's men" so uncomprehendingly. That "moment of resistance" in their gaze is what Walsh takes to be "his study of their hesitation . . . the kind of interest that holds its object at a distance." Walsh appreciates this recognition from Godard. She backtracks, acknowledging that he does use some green in his films: he uses sea-green and eau-de-nil and "a green that is almost black." She uses the color of paint, her medium, to describe his colors. she refuses in a sense to Grant his frame. "Godard plots are driven by desire.. Love is their by-product; beauty is their currency." But the women do not look as if they desire the men: "they prefer her to be desired without desiring." "Ethics are the aesthetics of the future," Bruno says. Godard showed Walsh the beauty and power of saying “J'hesite.”

8

True to New Narrative’s celebration of gossip, Rob Halpern drops a lovely morsel of blab in his introduction to Robert Gluck’s Jack the Modernist, originally published in 1985 — but with the thrill of a forthcoming NYRB reprint due out this year. As blab would have it, the character named Martin “is the confirmed nomen à clef of Fredric Jameson . . . whose article ‘Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism’ was first published in 1984, the year before Jack.” At one point in Jack, Bob (a.k.a. the narrator who goes by “Robert” on the cover page, where he plays author) writes: “If there was a Red Queen, she would have been Martin, a famous art historian and Marxist critic who really wielded some French majesty.” Of course the juiciest blab gets tucked into footnotes, which is why I read them with gusto. And Halpern’s footnote number 5 doesn’t disappoint: he nods to the role played by Fredric Jameson in the San Francisco Bay Area circles where New Narrative emerged during the late 1970’s, and mentions Jameson’s presence in Bruce Boone's Century of Clouds, where he appears undisguised as “Fred . . . the captain of our destinies and true Teddy Roosevelt of our souls.” Coincidentally, Boone's essay “Gay Language as Political Praxis: The Poetry of Frank O'Hara” appeared beside Jameson's "Reification and Utopia" in the first issue of Social Text in 1979.

In a note appended to the novel, Gluck locates the text in “art of collage” before offering an inventory of sources. Halpern hones in two of these sources to frame the intertextual references, adding that the title of the book comes from the “art criticism” of Denis Diderot and “the novelesque dialogue” deployed in Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist, where gossip and rumor create possibility. Gluck’s Jack, of course, is the modernist—his cool distance repulsed by intimacy and sentimentalism, eager to prove itself in abstraction. And Bob represents himself, which is to say: the postmodernist impulse of play, experimentation, and self-abnegation.

9

“Power of absence,” — as noted by Paul Valery in his Cahiers from 1929.

“We have to be in a desert. For he whom we must love is absent.” — replies Simone Weil.

10

Autumn 1940, according to Roberto Calasso— who notes that “Bertolt Brecht was writing The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, where Hitler is presented as a gangster trying to take control of the cauliflower racket.” Calasso continues:

Young Viereck couldn't know it, but in the introduction to Metapolitics he was already perfectly reiterating Brecht and many who would follow him: “The common question is: are the men on top, Hitler particularly, as sincere as the masses below or only cynical gangsters laughing at their own stolen ideas? But the very question is too heavy-footed, too lacking in psychological awareness, to answer either positively or negatively. Here the real question is not either-or. Both the 'either' and the 'or' combine; that combination is a logical impossibility but a psychological fact. In other words, most successful frauds are sincere; most demagogues are honestly intoxicated by their own dishonest and cynical appeals.”

11

Samuel Beckett: “Molloy and the others came to me the day I realized my stupidity. Only then did I start to write what I felt.”

12

McKenzie Wark to Cybele again . . . “There’s so many of their myths where the cut balls give rise to monsters. As if that could only be a bad thing. You and girls like me, Cybele, we love monsters. They’re modern. They demonstrate the ways the world could become otherwise. They’re the sign of fresh things. This is your world in all the ways it comes and cums.” — and my heart in the cumberbund.

13

Ah well. . . C’est comme ca, la vie. “Realism is a corruption of reality,” wrote Wallace Stevens in Opus Posthumous.

*

Anne Carson, Plainwater

Bruce Boone, Century of Clouds

Denis Diderot, Jacques the Fatalist

Greil Marcus, What Nails It (Yale University Press)

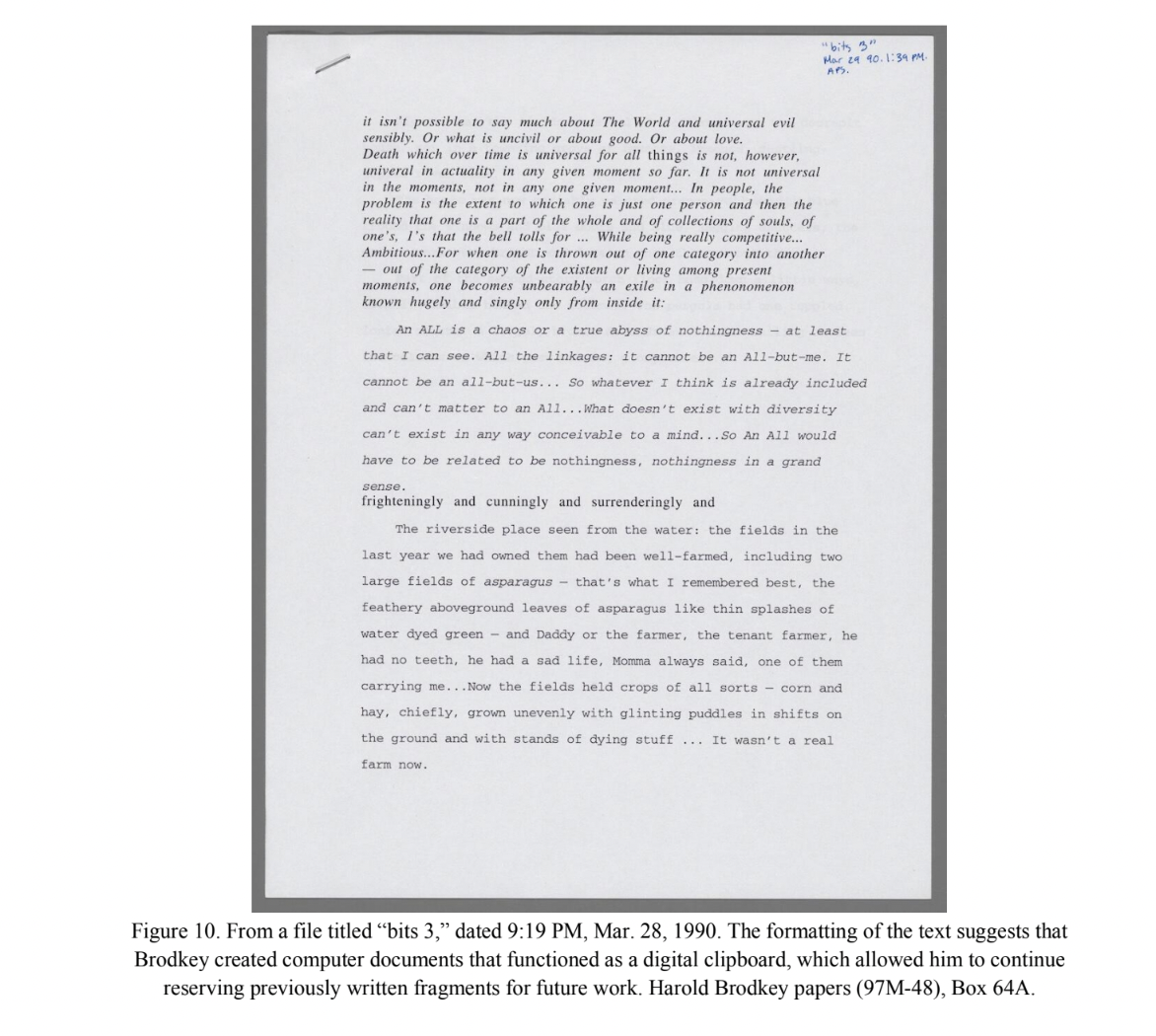

Jeff Noh, “Harold Brodkey’s Paper Attachments”

Joanna Walsh, My Life as a Godard Movie (Transit Books)

McKenzie Wark, Love and Money, Sex and Death: A Memoir (Verso)

Nadine Shaw, “Ville morose”

Paul Valery, Cahiers

Paul Zweig, The Heresy of Self-Love (Basic Books)

Robert Gluck, Jack the Modernist (NYRB Classics)

Roberto Calasso, The Unnameable Present (translated by Richard Dixon)

Egon Schiele’s 1911 painting of a “poet” — and it goes without saying that Schiele is the model for his imaginings and self-objectifications