“I didnʼt think it would turn out this way” is the secret epitaph of intimacy. To intimate is to communicate with the sparest of signs and gestures, and at its root intimacy has the quality of eloquence and brevity. But intimacy also involves an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way.

— Lauren Berlant, “Intimacy”

Rumor has it.

Rumor has it that Donald Barthelme was obsessed with the letter that Soren Kierkegaard wrote to his ex-fiance’s husband whose family name was Schlegel. As evidence would have it, the private letter that has never been made public inspired a short story by Barthelme titled “Kierkegaard Unfair to Schlegel.” It’s difficult to overstate how central this story remains to understanding what Barthelme was doing in literature.

Gossip and hearsay: these are the details that condemn humans in the court of public opinion. Every public has its own rumor mill, just as every intimate relationship has its hearsay.

But rumor has it that the writer Tyrtamus of Eressos only had sex intercourse once in his entire life, at the age of 47, with Aristotle's son. Trytamus (also known as the philosopher named Theophrastus) was Aristotle's favorite pupil, and the one-off lover of his son. But this character from Eressos remained unimaginable to me until Plutarch dropped the sort of lubricious detail that brings a dead man to life: “The offensive man is the kind who exposes himself when he passes married women on the street. At the theater he goes on clapping long after everyone else has stopped.”

What else — apart from rumor — does the work of fleshing-out small details in fiction and prose?

Those small things not speaking.

Plutarch believed that “small things” – an offhand remark, an aside, a quick dialogue, a joke, a ritual gesture – illuminated the subject of an essay more effectively than explanation and description. His essay “On the Failure of Oracles” rants and raves like a tell-all, offering a view behind the curtain into the secret practices of his job at the Delphi Oracle. Plutarch tells us how he unscrambled puzzles from the underground chamber where answers were received. He gives vent to his suspicion that the chamber was filled with hallucinogenic gas. The reader is given an intimate foretaste of how the genre of the “tell-all” creates buzz around a subject. Even the deconstruction of its secret parts seems to add to the mystery and marvel.

Could mention weather.

In his notebooks and writings, Roland Barthes was drawn to mundane everyday details about weather, schedules, clothing, lodging and biography – minutiae that fleshed out the sensorium of incarnation, artefacts of the ordinary. The immediate was relevant. Barthes felt there was more to learn from tactile consciousness than from what he called “insipid moral musings.”

Could mention the hair on his pillow.

The self is often identified with its loyalties and affiliations. The details that evoke such loyalties also tend to be the source of tension in human relations. Lush tidbits in the Sei Sonagon’s “pillow book.”

They say she dreamt the whole thing ten years before it happened.

Dreams are the form that can do absolutely anything. Never forget that. No part of a dream can be disproven. The data of dreams is non-falsifiable as a lived or received experience.

My mom used to remove the marrow from soup bones and put on it bread as a school sandwich.

The margins aren’t really tangents. Margins are the things we would say if we stop skewering language with the pretexts.

In his introduction to Urban Gothic, Bruce Benderson aligns his work with the French genre known as “textes” that offers a more capacious narrativity and blurs ontological boundaries. At several points in different stories, Benderson mentions “tenderness” in surprising contexts: when feeling overcome by an “irresistible reverence” for beauty that isn’t sexual, and just after being strangled by a john in a “contrived situation” that resembled “the feeling of love.”

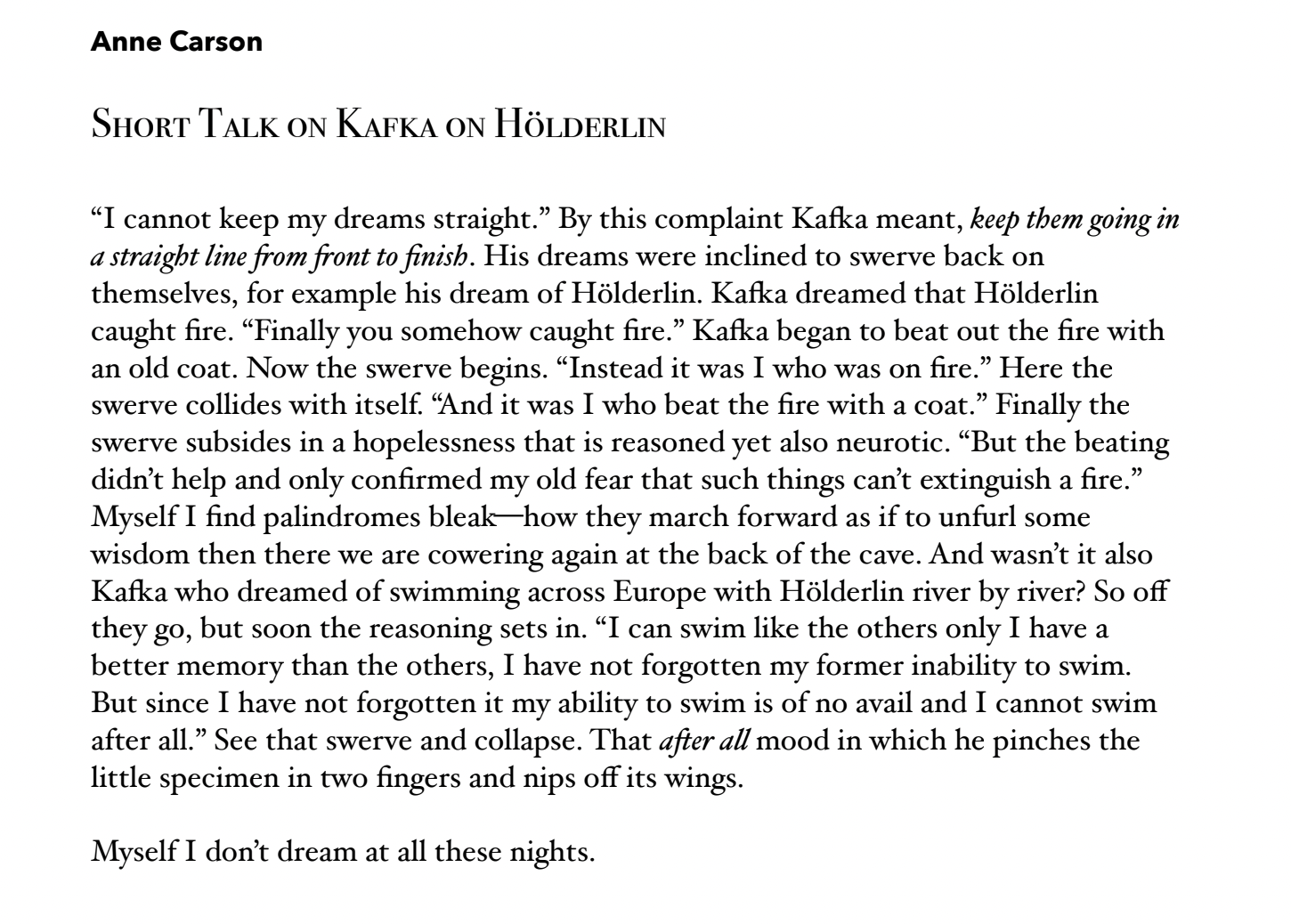

Yes, said Anne Carson. “The words we read and words we write never say exactly what we mean. The people we love are never just as we desire them. The two symbola never perfectly match. Eros is in between.”

*

Anne Carson, “Short Talk on Kafka on Holderlin”

Bruce Benderson, Urban Gothic (2022)

Donald Barthelme, “Kierkegaard Unfair to Schlegel”

Lauren Berlant, “Intimacy”

Magnetic Fields, “It’s Only Time”

Plutarch, “On the Failure of Oracles”

Sei Sonagon, The Pillow Book of Sei Sonagon (translated by Ivan Morris)