I journeyed to Fredensborg with two absolutely incredible horses—when they were supposed to stand, they fell down; when they were supposed to get up, they needed support; when they went slowly, they limped; but when they set off in a fast trot, they were the best runners.

— Soren Kierkegaard in his notebooks, at some point between 1840-1842

— Regine again.

Regine, whose favorite hero was Joan of Arc.

Regine, whose beloved could not imagine a heroine as flesh.

K, who made her his Beatrice, despite Regine’s protestations. The rose plant passed back and forth between them in early letters.

In Stages on Life's Way, Kierkegaard reprinted the note he sent to Regine when returning her engagement ring in 1841:

“Above all, forget the one who writes this; forgive a man who, even if he was capable of something, was nevertheless incapable of making a girl happy.”

Allegedly. The refrain in a word that nestles; a sinuation that nests.

In an essay titled “Love and Freedom of the Other,” Svetlana Boym considered the symbolic function played by Kierkegaard’s ring, and his references to it. “From a conventional symbol of union, the ring becomes a mysterious hieroglyph that finds its reflection in lovers' syntax (parenthesis) and body language (embrace),” wrote Boym. “In The Seducers Diary, it is Cordelia who breaks the engagement even though Kierkegaard believes that he has led her to it.” Boym continues exploring this “lovers’ syntax” by naming “the space around the wall” as “the space of their love in this world”: “Once they escaped and met near the cave, they were doomed to misunderstanding. He saw her bloodied clothes and rushed to kill himself, she followed him to the grave. Public disclosure threatens the authenticity of their love. The wall is neither merely an obstacle nor a synthesis, it is the space of the lovers' paradox, of the tragedy of the love experience.”

In K’s Repetition, there is that critical moment when the narrator looks at the young lover and says:

“Nothing could draw him out of the melancholy longing by which he was not so much coming closer to this beloved as forsaking her. His mistake was incurable, and his mistake was this: that he stood at the end instead of at the beginning.”

[This last bit appears in K’s sermon on the lilies as well, and had I more time or a heart less sooted, I’d comb through my notes and find it. . . .]

I’ve been chasing a thread — a confusion between the postman’s trumpet and the spyglass — through K. for months, trying to fasten it to my reading of Vigdis Hjorth, whose books I consumed in a tantrum of reading earlier this year. Who knows what may never come of it?

Michael Wood: “I have sought to remain loyal to this hesitation, whose other name, I believe, it’s not indecision or undecidability, but patience.”

K and I go way back.

And also [Again] through almost every book I’ve written— including My Heresies, with its tribute to the rosewood dresser. Despair has its creative moments and unexpected promises, as with the moment when a despairing Regine told Soren that she could stay out of his way and live in his cupboard, as a part of his furniture.

Let it be known that K was a man of his word to the end! After ending their engagement, Soren granted Regine’s wish by building a special Shrine for her in his home. As he put it:

“I had a rosewood pedestal made. It was constructed after my own design, and after the occasion of a word of hers. She said that she would thank me all her life if I would let her stay with me, that she would even live in a little cupboard. With this in mind it was constructed without shelves. In it everything is carefully preserved, everything that reminds me of her, everything that can remind me of her. Here also can be found a copy of each of the pseudonymous works for her; always they were reserved only to Vellum copies, one for her and one for me.”

[Again] being the condition of the postscript as a paratext, or an addendum to the apparatus of the letter.

[Again] being the addition to a letter K sent to Regine at some point in 1836, as recorded in his notebook. I quote:

Die stehn allhier im kalten Wind

Und singen schön und geigen:

Ob nicht ein süssuertraumtes* Kind

Am Fenster sich wollt' zeigen?

Your S.K.

Postscript: When you have forgotten everything that lies between, I would only ask you to read the salutation and the signature, for as I myself have become aware, it has the power to calm or to excite as have but few incantations.

Piedestal (Danish) a pedestal-like cupboard. Kierkegaard had such a cupboard, custom made, in which he kept letters etc. related to Regine. See also “palisander.”

One of the provisional titles for Fear and Trembling was a neologism by K, who foraged Mellemhverandre (meaning literally "between each other”) from the Danish word mellemuarende (something between two persons, a "between-being"). Mellemhverandre is found in "From the Papers of One Still Living” and The Concept of Irony.

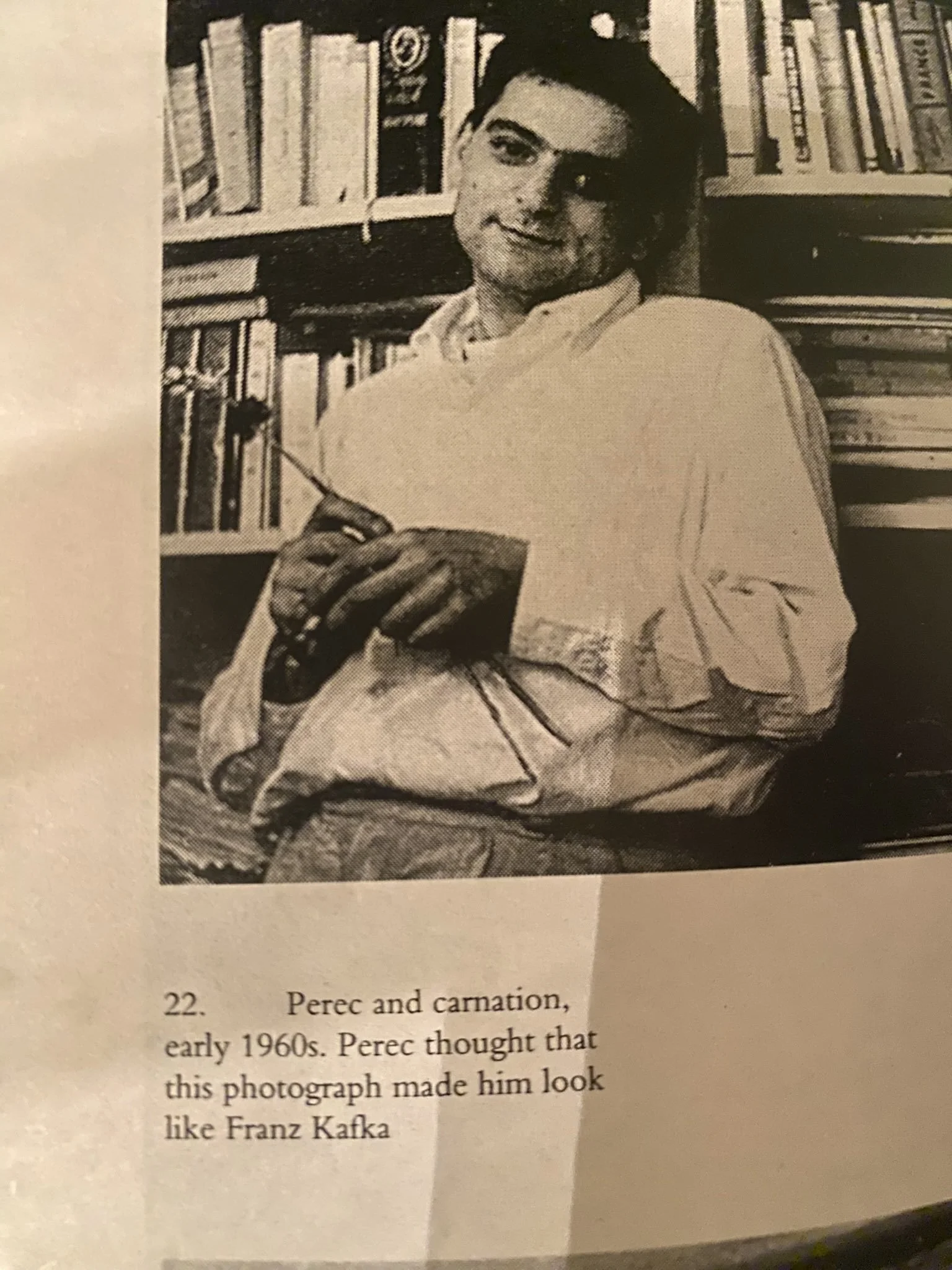

And a poem by Georges Perec, as translated by Jacob Bromberg —

I forgot to mention the nightmare! (I’ll come back to it when the days are a bit less hectic.)