“Something is absent, offered to you, perchance. A hole made in a poem; a poem made whole by a cut.”

– McKenzie Wark in a letter to Cybele

Boris Tishchenko, Requiem (1966), after Anna Akhmatova, for soprano, tenor and orchestra

1 - OFFICIALLY.

A simile is a figure of speech in which one thing is likened to another, in such a way as to clarify and enhance an image. It is an explicit comparison (as opposed to the metaphor, where the comparison is implicit) recognizable by the use of the words ‘like’ or ‘as.’

2 - ETYMOLOGICALLY.

“Simile” comes to English from the Latin similis, meaning like.

3 - NOTATIONALLY.

See Boris Tishchenko’s Requiem after Anna Akhmatova, for soprano, tenor and orchestra (1966), pictured above.

4 - COMPARATIVELY.

“Dreams resemble poems in their crucial mechanisms: compression, condensation, preference for metaphor to simile, and in how little time they take,” said William Matthews of the being shared by poems and dreams.

5 - PROVISIONALLY.

“A good simile refreshes the intellect,” said Ludwig Wittgenstein in the year 1929.

6 - ESOTERICALLY.

A “simile reveals more than what is already in that for which it has been chosen,” as Hans Blumenberg put it.

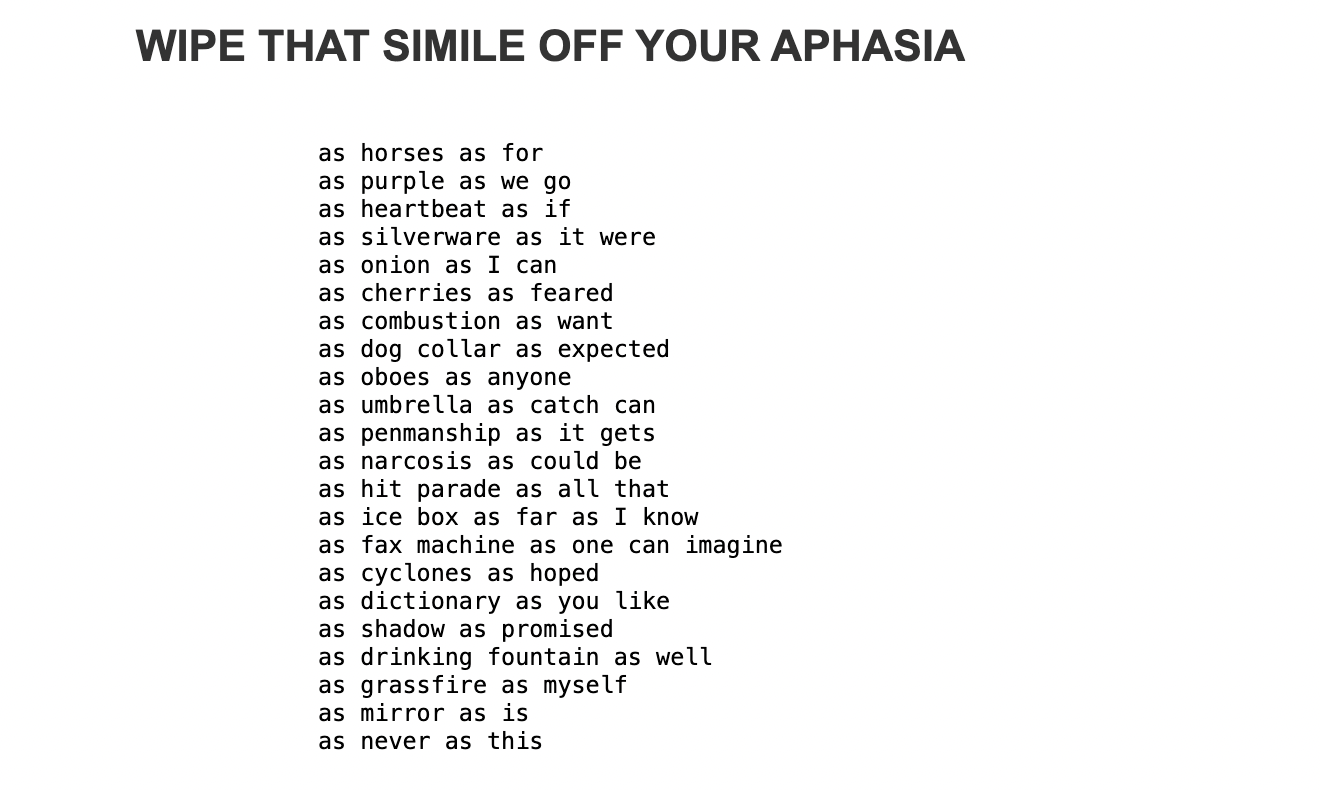

7 - TITULARLY.

Similes may glimmer as with Stephanie Burt’s “Like: A Speculative Essay About Poetry, Simile, Artificial Intelligence, Mourning, Sex, Rock and Roll, Grammar, Romantic Love”. Other similes may toot their poem’s horns brazenly, as with Albert Goldbarth’s “How Simile Works.”

8 - APPETITIVELY.

“Like that unpocketed peppermint which has, from fingering, become unwrapped, we always plate our sexual subjects first. It is the original reason we read…the only reason we write.” So wrote William Gass in On Being Blue.

9 - HALF-HEARTEDLY.

“But I shall leave my simile and I shall return my subject,” wrote Heinrich Kleist in an essay titled “On the gradual formation of thoughts in the process of speech”.

10 - REVERBISHLY.

Similitudes in Olivia Giovetti’s brief on graphic scores and Kurdi forms of notation that admit indeterminacy.

11 - IMPULSIVELY.

As If Only. This was the title of a small, limited edition sonnet corona I printed and passed out at a reading in Tuscaloosa, on the spur of the spur of the moment.

12 - DIEGETICALLY.

“As if I had become happy,” Mahmoud Darwish begins, in Fady Joudah’s translation.

13 - WITH AN EYE TO THE EXIT.

A simile may appear when a poem prepares to take leave of the reader. I’m thinking of how Sara Teasdale ended her poem, “The River,” where simile seals a final image that attests to the change the poem describes: “And I who was fresh as the rainfall / Am bitter as the sea”

14 - INVOKING ORAL TRADITION.

In an interview with Barbara Guest, Haryette Mullen cited the lines “hip chicks ad glib/flip the script” as a reference to the performance of female rappers Salt N Pepa who used rap as AIDS education through their song, “Let’s Talk About Sex.” Mullen told Guest: “When I sought a line to complete the quatrain that fit the rhythmic and phonemic patterning of the other three lines I’d written, ‘tighter than Dick’s hat band’ popped into my head, as an automatic simile that I’d heard throughout my childhood whether my mother or grandmother referred to tight clothing, or tight situations. But it was only in the context of the lines about female rappers, whose tight distichs (couplets) inform my own improvisational approach to rhythm and rhyme in this poem, that I grasped, for the first time, the origin of this folk simile: a metaphorical description of a condom. I saw a continuum, in terms of oral tradition or verbal performance style from my own matrilineal heritage—in a religious, lower middle class family that spoke of sexuality through metaphor, circumlocution, and euphemism— to the bold public style of today’s women rappers. The poem embraces all of that, while also using language as verbal scat. Print and electronic media, as well as orality, provide my materials.”

15 - AS A WAY INTO “IMAGINATIVE CRITICISM”.

Similes are central to critique in Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful, a book that pays tribute to the jazz musicians Dyer adored. The preface tells us how the piece will be played, namely by allowing the writing to be “animated by the defining characteristic of its subject.” All Dyer’s attention goes to his subjects; form and content do the work of co-creating a shape that deserves to be studied on its own terms, as an object that works in its own way, which may or may not be recognizable. Moving into his subject without invoking an authoritative elitism, Dyer practices what he calls “imaginative criticism,” a speculative telling that admits its debt to fiction. “Even the briefest simile introduces a hint of the fictive,” Dyer reminds us, since a good simile becomes emblematic to the reader. Associations build across paragraphs, and Dyer doesn’t try to tame them. His metaphors bloom into “episodes and scenes” with dialogue and action. Asserting his loyalty to the “improvisational prerogatives of the form” itself, as seen in his improvisation around the jazz standards and his use of quotation cribbed from the way quoting functions in music, Dyer speculates data and information into scenes.

Generally, musical scores don’t cite their quotations. That labor is left to the performer or the listener. Reading voraciously expands the field of possible recognition. This goes for music as well: the more you listen to, the more you can recognize. At a jazz performance (or a classical one), music-lovers are more likely to “overhear” conversations between the performer/composer and the quoted source. Although musicologists help listeners decipher the quotes, the composer's responsibility doesn’t include citation. Dyer, to his credit, applies the composer's expectation of his audience to the text. He doesn't bother with fastidious citations because this is jazz. This is music. The quotes blend in.

16 - INTERROGATIVELY.

“My pain is like . . . — what is my pain like?” asks Albert Goldbarth in “Like”. Ricard Selzer’s essay, “The Language of Pain”, circles the simile-despair that strikes us when attempting to describe pain.

17 - ASPIRATIONALLY.

Once upon a time, Friedrich Schlegel imagined a fragment that didn't aspire to wholeness, a fragment capable of standing as a smaller work of art divided from its surroundings. “It must be complete in and of itself, just like a hedgehog,” wrote Schlegel. But this simile flattens me. No matter how one looks at the hedgehog, the simile feels fruitless. What is uniquely complete about the hedgehog? The hedgehog is completed by our description of it, and this hedgehog, once it exists, is already tangled with its life, the conditions of its livingness, its food sources, its ecological niche, its particular habitat.

18 - SINUOUSLY.

“Shadows rise like water / white fences comb through their hair” as in Denise Levertov’s “Images for Odette”

19 - WONDROUSLY.

Srikanth Reddy’s “On Wonder” touches the simile beautifully.

20 - DISCURSIVELY.

Sometimes a gap entertains the possibility of a simile, perhaps because the simile agrees on its own transience.

21 - FOUNDATIONALLY.

“Despite those who say that poetry makes nothing happen, humanity continues to be built on the literary device of the simile: Love thy neighbor as thyself,” Mark Yakich wrote somewhere.

22 - INTERLUDICALLY.

Trying to eat while reading Dan Albergotti’s poem, “Listening to ‘Twin Peaks Theme’ while Thumbing a Smooth Stone Nine Months after Angelo Badalamenti’s Death” — and admiring his similes.

23 - SCORNFULLY.

Daniil Kharms actively denounced the simile, setting his mind against the “like” and the likening, opting for a more esoteric, mystic-inflected space which may have been influenced by his father’s pacifist spirituality, or the man his father became after decades of prison. Kharms et. al traded the simile for apophatic speech (using the language to negate itself). Apophasis is found in the writing of Christian mystics including the Philokalia, which Kharms read in 1926, alongside Gregory the Theologian.

24 - POSITIONALLY.

Denis Donoghue looked down on the simile’s feebleness when comparing it to the metaphor.

25 - ATHELETICALLY.

Robert Rauschenberg’s etchings of Dante’s Cantos leaned heavily on images of athletes engaged in physical activities. He used these images to map Dante and Virgil's journey through hell, to suggest movement, or to picture the characters' actions. In Canto XV, for example, an athlete running gives visual form to Dante's simile in the famous final lines in which Ser Brunetto, running to rejoin his band, is compared to the winning runner for the green cloth in Verona."

26 - OMINOUSLY.

“As the world grows more terrible, its poetry grows more terrible,” said Larry Levis, quoting Wallace Stevens.

27 - BRILLIANTLY.

A. E. Stallings said many wonderful things under the title “Shipwreck Is Everywhere”.

28 - DARKLY.

“Grieved like, pined like... Why must there always be a simile? Why must you drive always to first questions, way beyond the goalposts every time. Well, what do you keep sacking our quarterback for, when it comes to that.”

— Renata Adler, Pitch Dark

29. DOUBLY.

Haryette Mullen

30 - CONVERSATIONALLY.

One night in 1908, as Hans Richter journeyed home from anatomy class, the sculptor Max Krause, unexpectedly asked him what was his “special credo” might be. Although surprised, Richter replied without hesitation: “Cosmos seen from a charmed star, looking like a melody of forms and colors.”

31 - INTERTEXTUALLY.

Shortly before Krause asked this question, Richter had been reading Schopenhauer, who said that “the cosmos, looked at from a blessed star, should appear like a solved geometrical problem,” in Richter’s interpretation.

32 - COSMOLOGICALLY.

Hans Lichternberg’s desire to use the mineral ball a simile of the Earth had long been preceded by his seeing in the terrestrial body "a miniature tourmaline" 17—one of a long series of ideas that use miniaturization as an optical means to grasp the whole: a higher being might perhaps think the tree and plant cover of the earth a mold. The human optic on the universe could thus have arisen from the exaggeration of the incidental, and the preponderance of emptiness in the universe could be more exactly captured through a reversed telescope, because in that perspective "the most beautiful starry sky" would simply vanish.

Magnification also produces speculative analogies, above all with Lichtenberg's repeated fascinated viewings of the planet Saturn, which he regarded not as the exception but as the norm of planetary eidos. It leads to the forecast that Jupiter is also in the process of acquiring a system of rings, and to the still bolder speculation that the Earth is already like Saturn. The whole anthroposphere unfolds on the surface of the outermost ring, conceived as a solidified shell; it also supplies another explanation of the Earth's magnetism.

33 - DISLOYALLY.

Tristan Tzara’s poem, “Maison Flake” (from of our birds), gives us the chair that “is soft and comfortable like an archbishop,“ a figuration of speech in the form of the simile Tzara had repudiated in a dada manifesto. He was never faithful to himself, I think. That’s why he wanted to banish the weight of personhood, this idea of a voice, a language, a nation, a construction that could be faithful. Tzara preferred loyalty to fidelity.

34 - APOSTROPHICALLY.

TO HÖLDERLIN

We are not permitted to linger, even with what is most

intimate. From images that are full, the spirit

plunges on to others thar suddenly must be filled:

there are no lakes till eternity. Here,

falling is best. To fall from the mastered emotion

into the guessed-at, and onward.

To you, O majestic poet, to you the compelling image,

O caster of spells, was a life, entire; when you uttered it

a line snapped shut like fate, there was a death

even in the mildest, and you walked straight into it; but

the god who preceded you led you out and beyond it.

O wandering spirit, most wandering of all! How snugly

the others live in their heated poems and stay,

content, in their narrow similes. Taking part. Only you

move like the moon. And underneath brightens and darkens

the nocturnal landscape, the holy, the terrified landscape,

which you feel in departures. No one

gave it away more sublimely, gave it back

more fully to the universe, without any need to hold on.

Thus for years that you no longer counted, holy, you played

with infinite joy, as though it were not inside you,

but lay, belonging to no one, all around

on the gentle lawns of the earth, where the godlike children had left it.

Ah, what the greatest have longed for: you built it, free of desire,

stone upon stone, till it stood. And when it collapsed,

even then you weren't bewildered.

Why, after such an eternal life, do we still

mistrust the earthly? Instead of patiently learning from transience

the emotions for what future

slopes of the heart, in pure space?

Rainer Maria Rilke (translated by Stephen Mitchell)

35 - POLYPHONICALLY.

From Paul Klee’s notebooks dated July 1881:

Thoughts at the open window of the payroll department. That everything is transitory is merely a simile. Everything we see is a proposal, a possibility, an expedient. The real truth, to begin with, remains invisible beneath the surface. The colors that captivate us are not lighting, but light. The graphic universe consists of light and shadow. The diffused clarity of slightly overcast weather is richer in phenomena than a sunny day. A thin stratum of cloud just before the stars break through. It is difficult to catch and represent this, because the moment is so fleeting. It has to penetrate into our soul. The formal has to fuse with the Weltanschauung.

Simple motion strikes us as banal. The time element must be eliminated.

Yesterday and tomorrow as simultaneous. In music, polyphony helped to some extent to satisfy this need. A quintet as in Don Giovanni is closer to s than the epic motion in Tristan. Mozart and Bach are more modern than the nineteenth century. If, in music, the time element could be overcome by a retrograde motion that would penetrate consciousness, then a renaissance might still be thinkable.

We investigate the formal for the sake of expression and of the insights into our soul which are thereby provided. Philosophy, so they say, has a taste for art; at the beginning I was amazed at how much they saw. For I had only been thinking about form, the rest of it had followed by itself. An awakened awareness of "the rest of it" has helped me greatly since then and provided me with greater variability in creation. I was even able to become an illustrator of ideas again, now that I had fought my way through formal problems. And now I no longer saw any abstract art. Only abstraction from the transitory remained. The world was my subject, even though it was not the visible world.

Polyphonic painting is superior to music in that, here, the time element becomes a spatial element. The notion of simultaneity stands out even more richly. To illustrate the retrograde motion which I am thinking up for music, I remember the mirror image in the windows of the moving trolley. Delaunay strove to shift the accent in art onto the time element, after the fashion of a fugue, by choosing formats that could not be encompassed in one glance.

36 - HOMERICALLY.

Among the techniques Homer used in The Aeneid, we find invocation to the Muse, the expanded simile, the conventional or repeated epithet, and the use of the supernatural to influence events. Vergil would borrow these, as would many others.

37 - HOPEFULLY.

And to you, reader—let us here recall together William Carlos Williams's famous lines— “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die Miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.” Let us embrace the good news, which is that we do not have to be like these miserable men. There is so much crazy shit we can stuff into our mouths, with or without the simile.

— Maggie Nelson, Like Love

38 - AS PART OF “A SINGLE SEMANTIC STREAM”.

[In 1933] Mandelstam read the essay [Conversation about Dante], read his poems, and talked copiously about poetry and about painting. We were struck by the remarkable affinities between the essay, the poems, and the table talk. Here was a single semantic system, a single stream of similes and juxtapositions. The image-bearing matrix from which Mandelstam's poems emerged became strangely tangible.

— Lidiya Ginzburg, “Poetika Osipa Mandelstama” in Izvestia Akademia Nauk SSR, July-August 1972, translated by Sona Hoisington in Twentieth Century Russian Criticism, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975

39 - FIRST-CONFESSIONALLY.

The Catholic Church understood Freud's concept of the superego centuries before he articulated it in 1940. The cathedral on a hill is its palpable and visible representation, or, in Freud's simile, the superego is “like a garrison above a captured town.” In the case of the church, it is a garrison so effective that it doesn't even need soldiers. Its windows are beautiful. Its frescoes and painting and sculptures, depicting absence in enormous detail, are priceless. It enabled Dante to imagine hell, and it was at least the stepmother to a ninety-year period of Italian art, a period of corruption, betrayal, incest, assassination, intrigue, and unsurpassable art. The church knew beautv and evil were sleeping together, and gave doth allowances to do it. Iwo thousand years of stolid, industrious virtue and Swiss peace perfected the cuckoo clock and the dairy cow. I suspect the Swiss dairyman had a good deal of placid self-esteem. Michelangelo hated himself. And a later figure, Caravaggio, was mean-tempered, an inadvertent murderer whose self-portrait, as Goliath, is full of self-contempt and despair.

In the Age of Therapy, First Confessions could be seen as a ritualized form of child abuse, psychological in method, permanent in effect. But you can't take the Vatican to court. The painting on the chapel's ceiling doesn't respond to a summons and is tricky evidence.

In my case, I would lie awake as a child, full of vague yearnings which were sexual, which I did not know were entirely normal. I was never abused nor molested nor violated as a child. I simply felt that I was a violation, that I was guilty of being alive.

But if it was a violation, it was a pleasure. Besides, how guilty can anyone feel, at seven or eight? I was a boy like other boys. I didn't rebel against guilt, I forgot about it.

— Larry Levis, “First Confession”

40 - EVENTUALLY.

The final day of notes for Roland Barthes’ projected work, Vita Nova, was September 2nd, 1979. In these notes, Barthes referred to “Account of my evenings ( endless, futile diachrony)”, and quotes Pascal’s Pensees again, “Fragments: like the remains of an Apology for something.”