DELAHAYE: Are you still interested in literature?

RIMBAUD: I don’t think about that anymore.

— dialogue between Rimbaud and his friend in 1879, from Peter Weiss’ notes for “Rimbaud”

1. 23. 26

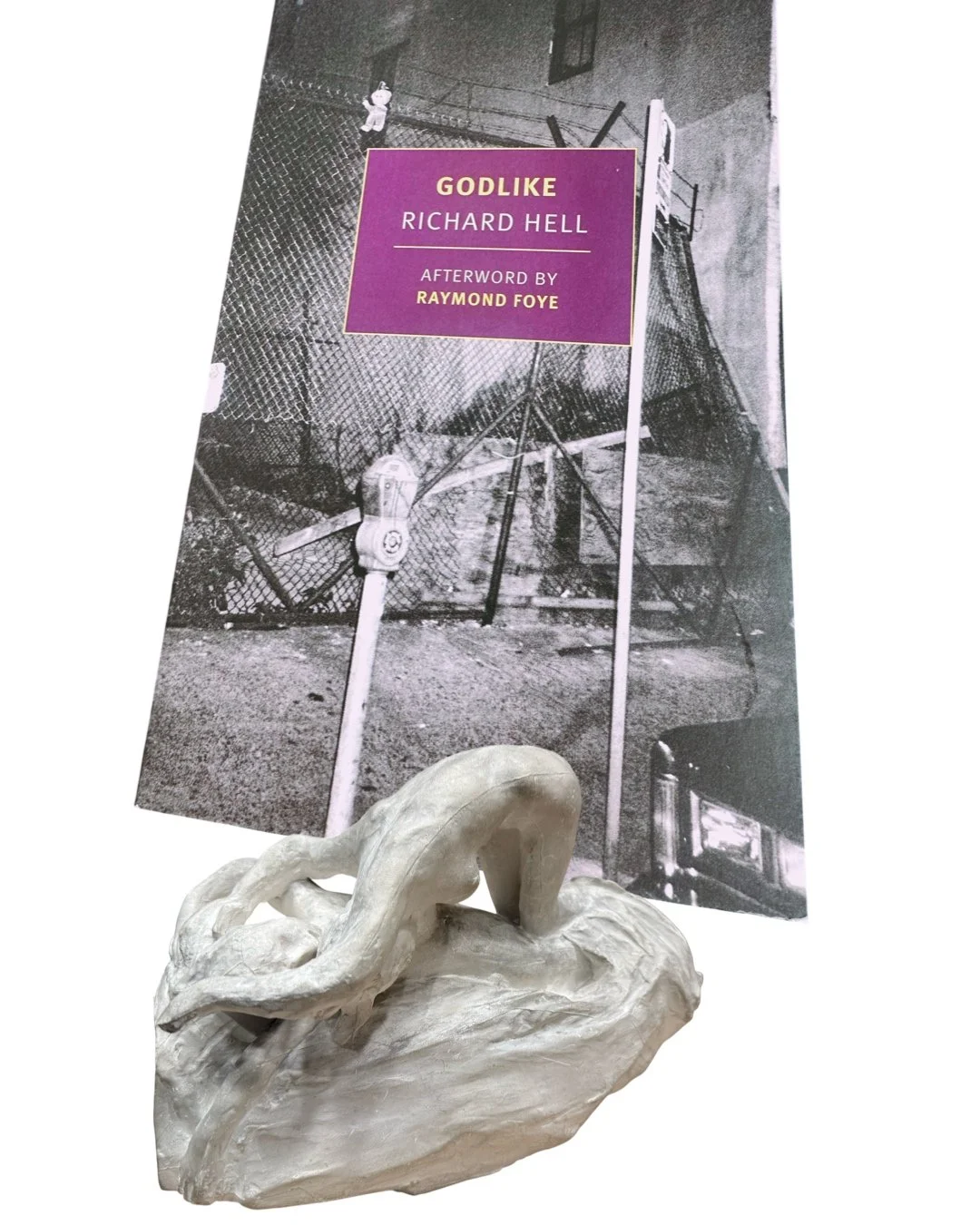

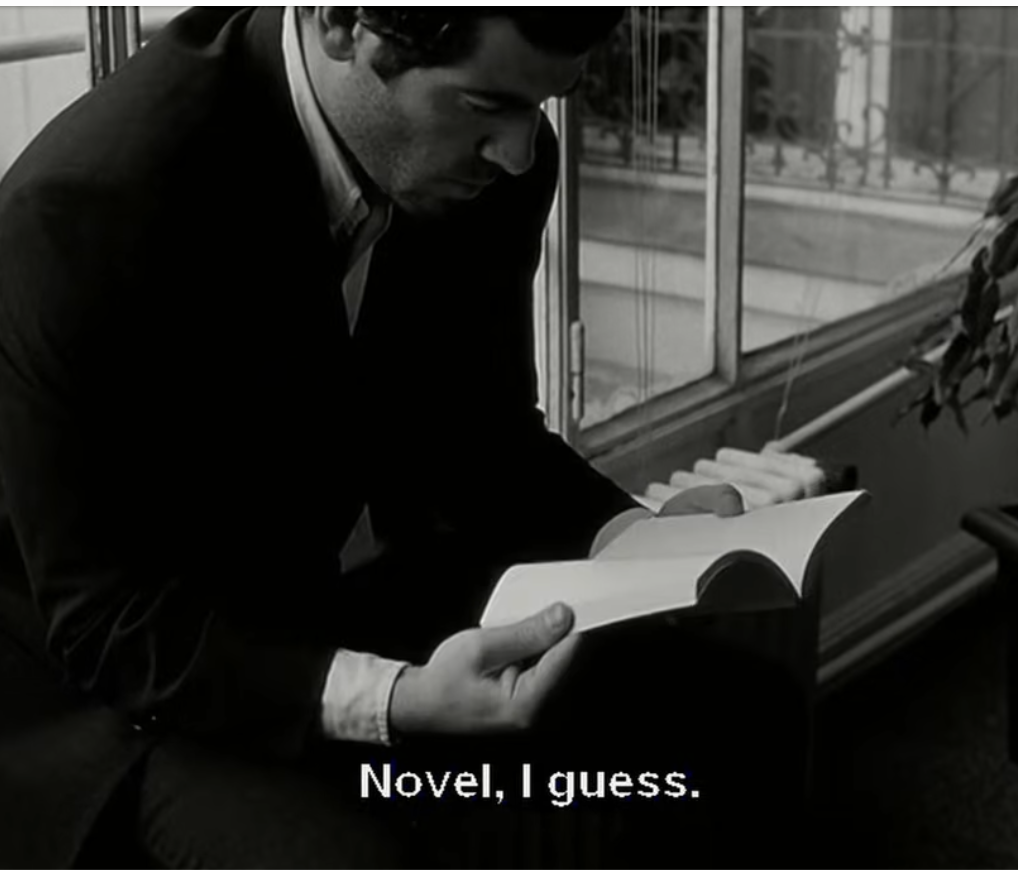

It was sitting on the doorstep in a cardboard envelope. Godlike by Richard Hell. A book that begins in the key of Verlaine meeting Rimbaud, transposed into New York City, lodged in the small studios that held various bodies that wrote from immediacy. An affect that lives somewhere between New Narrative’s practices of promiscuous citation and 19th century decadent self-fashioning. An aura of Proustian wistfulness. An intensified description of events involving scatology and sexuality. An urge to shift into poesie when the moment demands it. An iconic portrait of the Rimbaud we poets channeled and sought from so many midnights. A set piece in the mythography of the American punk scene. “A novel, I guess,” to quote Godard’s In Praise of Love.

Godlike begins in the key of spring: “It was March and the weather was like a pornographic high-fashion magazine.”

1.24.26

The book’s full title is Godlike: The Hospital Notebooks of Paul Vaughn incorporating his memoir-novelette of R. T. Wode. And there is an introduction written by “Paul Vaughn,” dated 2004, that describes the narrator’s reason for writing “in the form of a novel.” The scenes feel familiar, like reading Rimbaud again for the first time at 18. And then again at 23. And then reading him in multiple translations in your mid-30’s. And then obsessing over him when you turned 40.

Leaving these multiple (personal) encounters aside, Hell describes the “tedium” of the older married man and his young poet lover as they loaf towards writing:

They spent the greatest amount of their time together reading and writing and sometimes talking in T's apartment. These were probably their best times too despite being experienced largely as tedium. They preferred the times of thrills, bur the thrills grew out of the tension; and the mild, mildly restless, half-frustrated times of the many nights and late afternoons of doing almost nothing in T's apartment, or walking the streets without direction, were their true lives.

T's room was like some kind of glum office in its lack of daylight and its featurelessness, but with the little pictures now tacked on the walls, and the typewriter and sheets of paper, and the drugs, it got some character. He'd picked up a few stray pieces of furniture on the streers, including a table and three chairs, crates for shelves, and a bear-up old oriental rug. There was a secondhand portable record player too and a few albums.

They drank coffee and beer and sometimes codeine cough syrup and sometimes smoked some grass or snorted a little THC or mescaline and every once in a while a tiny bit of heroin, but mostly they lay around and lazily, impatiently goofed and wrote and complained, goading each other. Sometimes in the middle of the night one of them would go out for a container of fresh ice cream from Gem Spa. They'd go to a movie sometimes, or wander the rows of used bookstores on Fourth Avenue, or drink in a bar, but most of the time was spent in the dim back apartment.

The days and nights were as endless as wallpaper patterns. Boredom and irritation were normal and lengthened out into sometimes-mean giggles and into pages of writing. Writing was their pay. Books were reality. The room was a cruder dimension-poor annex to the pages of writing. The writing, as casual as it was—smeared eraseable typing-pages with revisions scribbled on and crumpled pages of rejected tries—was the brightly lit and wildly littered universe erupting out from the dark, poor, inexpressive room.

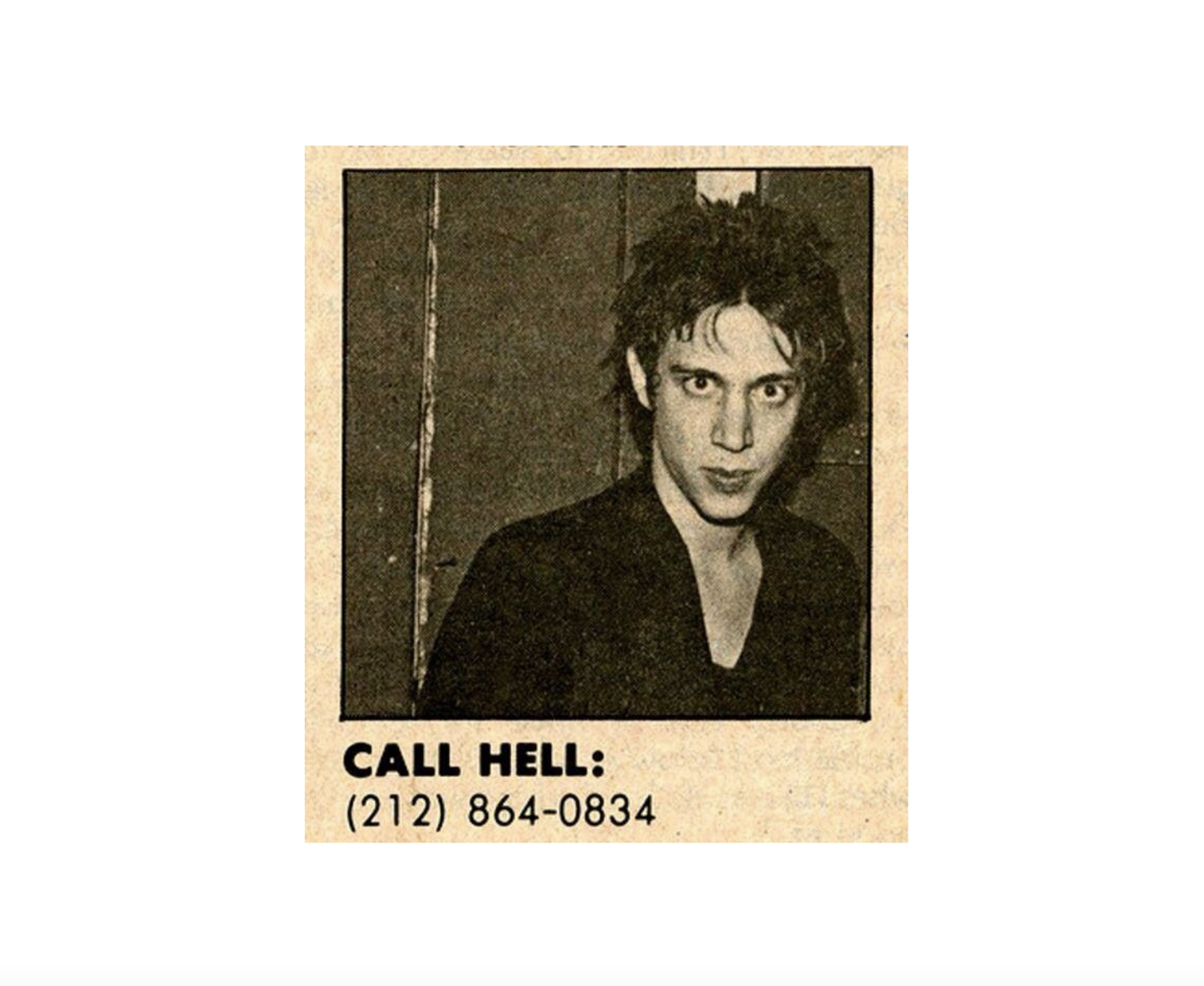

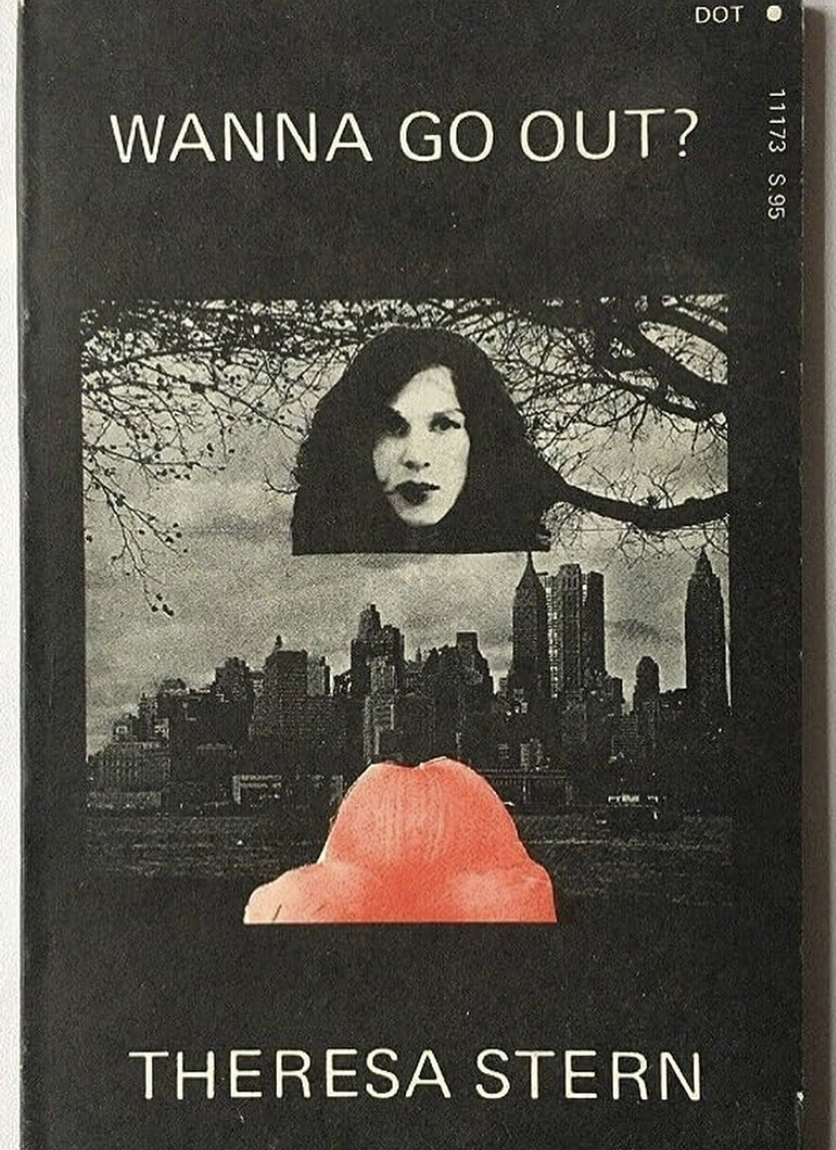

Part of the description matches what what we know of Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine’s love affair, but Hell also had personal experiences to draw upon. In 1973, Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell published a collaborative poetry book titled Wanna Go Out? under the pseudonym “Theresa Stern.” The photo on the book’s jacket is a composite of Tom and Richard dressed in drag (flip through the slides below to see it).

Hell’s Godlike puts flesh on punk’s philosopher-poets. Punk has always been committed to crossing lines, dirtying the parlor, waxing scatalogically about the skyline, transgressing boundaries of decency, gentility, and propriety. The fascist skin-heads on punk scenes are a sort of incoherence, since purity-driven punk grabs is meaningless. It follows from nothing. At its least interesting, punk flirts with nihilism. But any notion of hygiene in punk is ridiculous. And fascism thrives on hygiene. Fascism would not exist without the ministry of social hygiene stomping through our heads. Fascism fears anything queer or trans—anything transformative, really. Any process of transformation that reveals our inherent fluidity is anathema to fascists.

1.25.26

I micro-dosed Hell’s Godlike over the course of a weekend to keep it from ending too quickly.

Between doses, I re-grazed Alan Badiou’s In Defense of Love, a text based on a conversation that continues to provoke and inspire me. Love, as Badiou sees it, cannot be rendered riskless: it always asks more than we are capable of imagining or knowing. It cannot offer the sort of obliging transcendence enshrined by Romanticism and Goethe. “At the end of Faust, Goethe was already asserting that ‘the eternal feminine takes us Above’,” says Badiou, who finds this reliance on the eternal feminine “rather obscene”.

Badiou can speak for himself, of course, in this extended quote:

Love doesn't take me “above” or indeed “below”. It is an existential project: to construct a world from a decentred point of view other than that of my mere impulse to survive or re-affirm my own identity. Here, I am opposing “construction” to “experience”. When I lean on the shoulder of the woman I love, and can see, let's say, the peace of twilight over a mountain landscape, gold-green fields, the shadow of trees, black-nosed sheep motionless behind hedges and the sun about to disappear behind craggy peaks, and know - not from the expression on her face, but from within the world as it is - that the woman I love is seeing the same world, and that this convergence is part of the world and that love constitutes precisely, at that very moment, the paradox of an identical difference, then love exists, and promises to continue to exist. The fact is she and I are now incorporated into this unique Subject, the Subject of love that views the panorama of the world through the prism of our difference, so this world can be conceived, be born, and not simply represent what fills my own individual gaze. Love is always the possibility of being present at the birth of the world.

And Hell can speak for himself in this recent memory:

And I could speak for hours about the places where Alain Badiou’s words meet those of Richard Hell in the godly and godlike, but instead I shall let the wonderful Badiou (again) speak for himself, in the hands (and the head) of William Williamson:

1.26.26

Badiou’s praise of love chimes alongside that of Jean-Luc Godard, whose 2021 movie consists entirely of conversations and dialogues and monologues on Godard’s favorite subject.

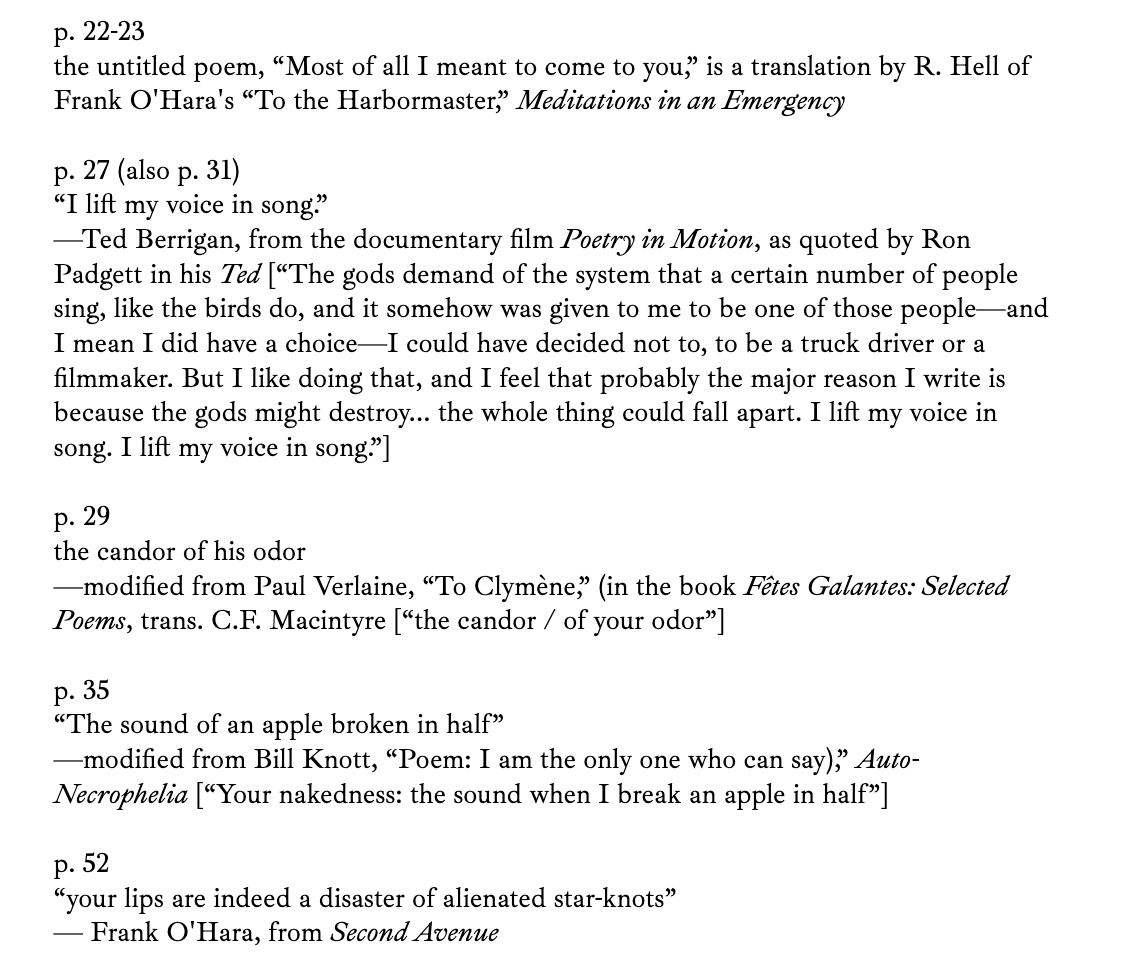

There is an interesting slippage between what Godard does in curating and transposing these images and texts and what Richard Hell does in his translations — as cited in the apparatus titled “Godlike Supplement” at the end of Godlike, where the note lists “R. Hell” as the translator of Frank O’Hara.

I am greedy for this sort of pluck and punk in translation theory. Greedy for the play of “I am the only one who can say,” to quote Hell’s quotation of Bill Knott.

PAST LIFE really is a text, a work, a novel. The things you think happened aren't any more true than a book. Lives differ as much in their complexity as books or movies. Books and movies are better though because their characters don't have feelings. So let's Ay, my darlings, into the leaning heights of folded linen. It's all smudged and smeared. Those bony boy's buttocks of his, I didn't have much to compare them to; to me they were the rear view of his hardon, or what his cock was hidden by, or the way to his cock. I haven't seen too many men's behinds and I never had that gay thing about boys' butts really (while I do like women's) ... Meanwhile, an Other's perception of the "same" events is so unlike one's own. Yes, we do operate in these scarcely overlapping fields, calling to each other from great distances, colors and sounds and smells and tastes incommunicable. Butting up against each other: only touch, touch which is to stimulate the sense receptors of another with one's own same class of sense receptors. Though this is true also in a limited way of the senses of taste and smell, which perhaps is why to kiss is the most intimate: tongue tasting tongue, nose smelling nose, face feeling face. Prostitutes often don't allow kissing. To kiss is to share the world most completely.

— Richard Hell, Godlike

1.27.26

In 1969, Peter Weiss drafted a skit titled “Rimbaud.” And I began this post with an excerpt from Hunter Bolin’s translation of it.

Paternity comes up in Weiss’ skit, when Rimbaud — who didn’t know who his biological father had been — answers a friend’s question by saying: “Just as there was no dick from whence I eddied into the egg, so there is also no world there that would receive someone like me.”

On that note, I encourage you to read this reprint of Godlike — the “Afterword” by Raymond Foye illuminates hell so well.

I leave off where I started in a sense, which is to say — with a grin that spreads like a Cheshire cat over Hell’s last words, as appended to the section titled “Supplement”:

excerpted from the section titled “Supplement” in Richard Hell’s Godlike (NYRB Classics, 2026), pp. 158-159

“It's funny to be living in an imaginary place, but I love the past of blaze and haze. We know that there's a sense in which everything's brilliant and I'll pretend to it.”

— Richard Hell, Godlike

*

Alain Badiou with Nicholas Truong, In Praise of Love translated by Peter Bush

Jean-Luc Godard, In Praise of Love (2021)

Peter Weiss, Rimbaud (Tripwire Pamphlet #11, 2021) translated by Hunter Bolin

Richard Hell, Godlike (NYRB Classics)

Richard Hell on collaboration

Richard Williams on Verlaine, Hell, Eno, and Television

Richard Hell playing live At Bunky's on March 28, 1985

Richard Hell reading poetry and Baudelaire-ing at Frieze Poetry Marathon 2009

Television’s Ork Loft Tapes from 1974

Television, “Marquis Moon”

Tom Verlaine, “Bomb”

William Williamson, “Lovesick: The Question of Love” a film about Badiou’s philosophy

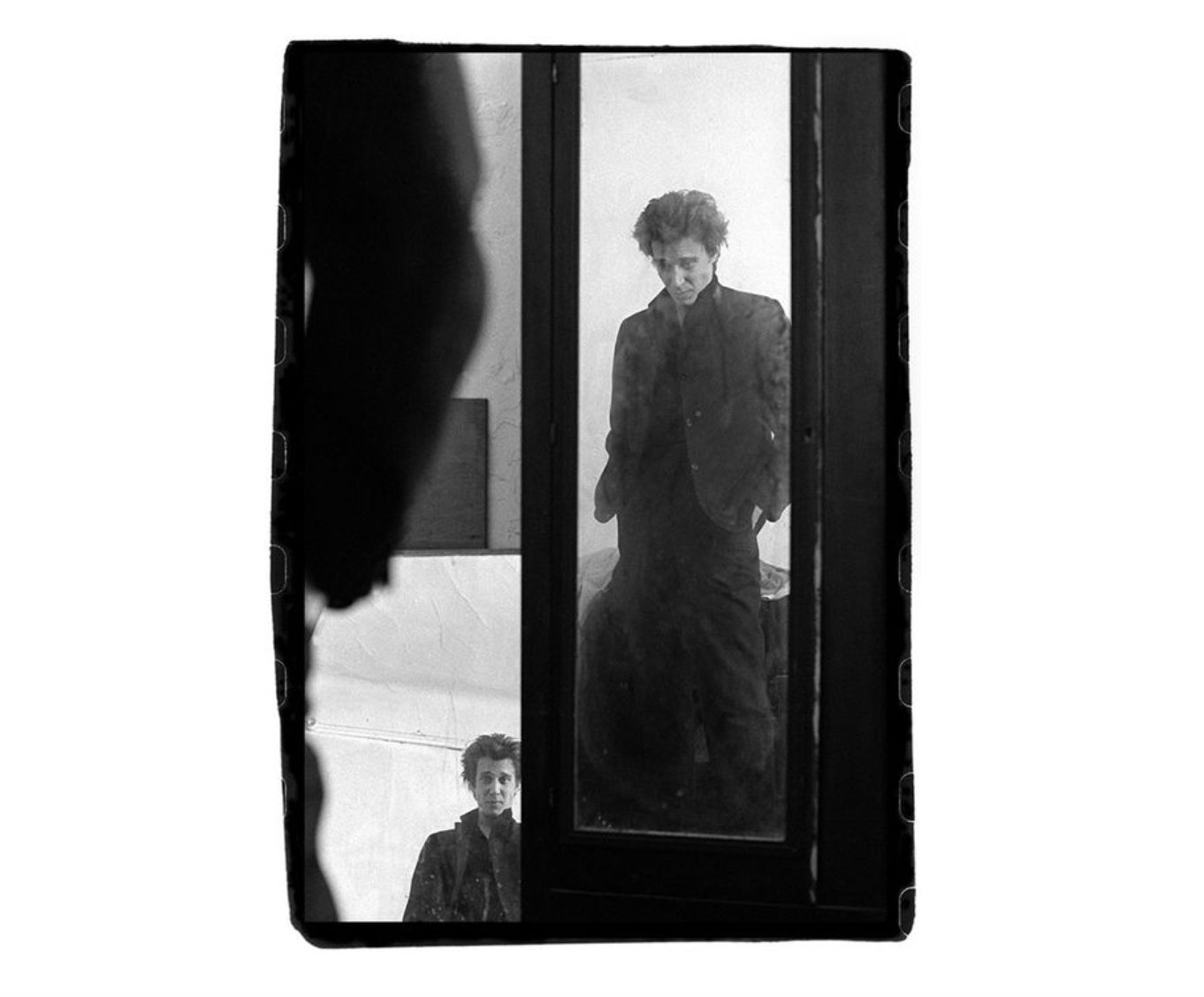

Richard Hell, New York City, by Stephanie Chernikowski