“If you look attentively at an animal, you get the feeling that a man is hidden inside and is making fun of you.”

— Elias Canetti, as quoted in Jean Baudrillard’s Fatal Strategies

“But I do know what I want here: I want the inconclusive. I want the profound organic disorder that nevertheless hints at an underlying order. The great potency of potentiality.”

— Clarice Lispector, The Passion According to G.H.

1

Oh draw at my heart, love,

Draw till I'm gone,

That, fallen asleep, I

Still may love on.

I feel the flow of

Death's youth-giving flood

To balsam and ether

Transform my blood --

I live all the daytime

In faith and in might

And in holy fire

I die every night.

— Novalis, Hymns to the Night

In 1797, a few months after tuberculosis killed his beloved fiancee, Sophie von Kühn, Novalis added the following words to his diary: The lover must feel this gap eternally and keep the wound open always. God grant me to feel eternally this indescribable pain of love – the melancholic remembrance – this courageous longing – the manly resolution and the firm and fast belief. Without my Sophie I am absolutely nothing – With her, everything.

Four years later, Novalis also succumbed to tuberculosis.

2

In 1888, Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling committed their thoughts on theory and poetry to paper. As Karl Marx’s youngest daughter, Eleanor was in a position to relay her father’s opinions on the Romantic poets who’d nfluenced his own poetry-writing days. And relay them she did, writing, The true difference between Byron and Shelley consists in this, that those who understand and love them consider it fortunate that Byron died in his 36th year, for he would have become a reactionary bourgeois had he lived longer; conversely, they regret Shelley’s death at the age of 29, because he was a revolutionary through and through and would consistently have stood with the vanguard of socialism.

This “true difference” jangles formula rather than resonance. In this, it resembles Karl Marx’s love-addled poems to the woman who would become Eleanor’s mother.

Perhaps no difference is true, though some differences are more compelling than others. I’m thinking of a sentence in which Heather Love compares the two revolutionists who find themselves dying at the end of Sylvia Warner Townsend’s After the Death of Don Juan (1938) to Walter Benjamin’s soothsayers who “can promise nothing; all they have to offer is the depth of their longing.”

3

“By ‘I’, I mean an unknown number of individuals,” wrote Kathy Acker in I Dreamt I Was a Nymphomaniac.

The dedication of Jeff Alessandrelli’s novel, And Yet, reads: “For my selves.”

Like poetry, And Yet is barely autobiographical and yet wholly true, a dialogue between sexual ideals and the constructions of selfhood. The speaker self identifies as a prude, and this identification suffers against the uses of erotic capital in the 21st century. The first three pages repeatedly mentioned the “lack”, the lacking, the not-having of this capital that seems to be abundant.

“Love is an anxious fear,” Allesandrelli admits, quoting Ovid, and thereby calling into play the lover's obsession with his “many different selves,” all of which make it inevitable that the beloved, too, has other selves. Unlike the lover, however, the beloved cannot be trusted. The beloved must be one self: and that self is created by the lover. Fucking is part of prudery here: “as hypersexual so as not to have to deal directly with what one actually feels, who one actually is.”

Another definition of prudery: “the daimon haunting one's life being mistaken for the person living it.”

4

When Tracey Emin’s Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 was incinerated in the 2004 Momart warehouse fire, she responded to the loss of her artwork by saying, “The news comes between Iraqi weddings being bombed and people dying in the Dominican Republic in flash floods, so we have to get it into perspective.”

As Hera Lindsay Bird puts it in a poem titled “Jealousy”: “imagine dating someone worse than yourself on purpose / that’s the kind of fucked up thing only everyone I’ve ever loved would do”.

Arnold Schönberg, Walking Self-Portrait (1911)

5

I pause near a portion of Charles Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal that was crucial to Walter Benjamin’s formulation of aura:

Nature is a temple whose living pillars

Sometimes give forth a babel of words;

Man wends his way through a forest of symbols

Which look at him with their familiar glances.

As long-resounding echoes from afar

Are mingling in a deep, dark unity,

Vast as the night or as the orb of day,

Perfumes, colors, and sounds commingle.

Despite all this commingling, despite the correspondence between hearing and smelling in Proustian time, there is little “scented music” in life. Taste relies on smell, a fact I know well from having lost both for a year after a head injury.

An English chemist named George William Septimus Piesse discovered the “notes” in scents. His The Art of Perfumery, and Method of Obtaining Odors from Plants was published the year after musical scales were first standardized. Drawing on the correspondences between sounds and smells, Piesse introduced what he called a “scent scale” which paired each of 24 musical notes with a scent. This “octave of odors” resembled the octave in music.

Piesse thought that citron, lemon, orange peel, and verbena formed “a higher octave of smells, which blend in a similar manner.”

6

Smound is defined as “a perception or sense experience created from the convergence of scents and sounds in the brain.” A portmanteau of ‘smell’ and ‘sound’, the smound was first approached in 1862 by Piesse, who wrote that “scents, like sounds, appear to influence the olfactory nerve in certain definite degrees.” Symbols look back at man with their familiar glances and smounds, to append Baudelaire.

Elsewhere, in Ashbery’s “Syringa”: The different weights of the things.

7

In a 1989 production of Prokofiev’s opera, Love for Three Oranges, scratch-and-sniff cards were distributed to audience members, but the act of scratching disrupted the flow of the performance.

8

“Affective ventriloquism” occurs when the brain associates sensations and transfers these effects across perceptual media. According to a study in 1978, where Steve Reich's Piano Phase was played at 40% versus 80% original tempo as the low and high arousal musical stimulus, vulnerable subjects can be made “to believe that they have perceived assent simply by presenting a sound,” as seen when a few listeners “repeated olfactory sensations when an ultrasonic tone (actually silence) was played across the airwaves.”

“There’s no salvation without the immediate, but man is it being who no longer knows the immediate,” Emil Cioran wrote in Pe culmile disperării. Man, for Cioran, “is an indirect animal.”

*

Ivo Perelman,The Passion According to G.H. (2012)

Jeff Alessandrelli, And Yet (Future Tense Books, 2024)

John Ashbery, “Syringa”

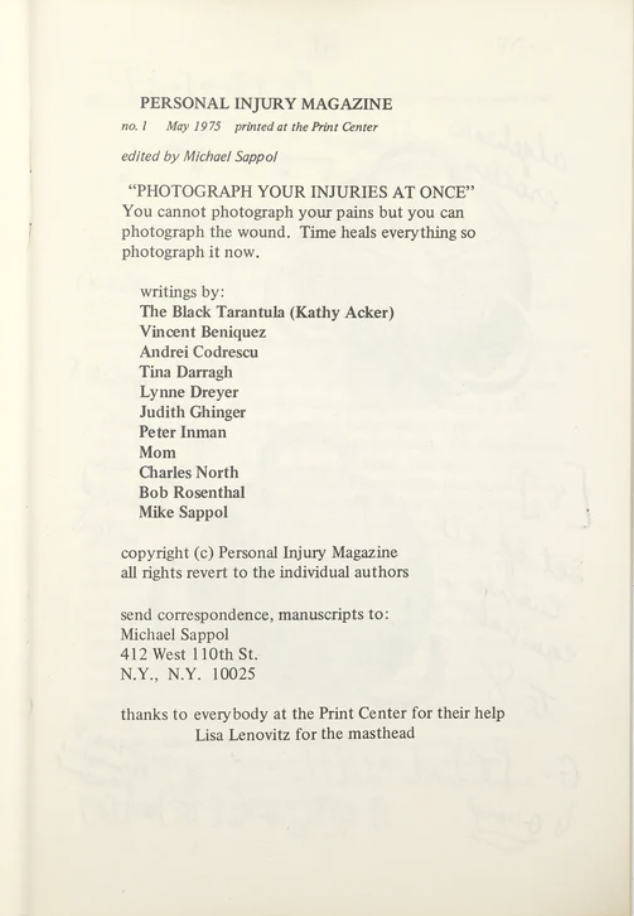

Michael Sappol, ed. Personal Injury Magazine (1975)

Valentin Radutiu and Marcus Rieck, “Interlude” (2015)