a freedom which excludes is less than free

— James Schuyler, “Immediacy is the Message”

I could go on. I go on.

This is why I love James Schuyler.

He doesn’t care

that “the plants against the light

which shines in”

is a dull observation. Or that

”Trees, and trees, more trees”

is just the layered visual experience

we all have in the forest, waiting

to let ourselves take in the sign

to turn back, go home

and really hate someone.

— Emily Skillings, “The Duke’s Forest”

*

In celebration of Emily Skillings’ delightfully-furious new collection, Tantrums in the Air, I returned to James Schuyler’s sharply-chiseled lines this week, admiring his inventorying eye, his corduroy-smooth syntax, and how closely he hewed to the syllabic texture of sound, particularly in his Letter Poem series.

LETTER POEM #3

The night is quiet

as a kettle drum

the bullfrog basses

tuning up. After

swimming, after sup-

per, a Tarzan movie,

dishes, a smoke. One

planet and I

wish. No need

of words. Just

you, or rather,

us. The stars tonight

in pale dark space

are clover flowers

in a lawn the expanding

universe in which

we love it is

our home. So many

galaxies and you my

bright particular,

my star, my sun, my

other self, my bet-

ter half, my one

A series of small things make this poem a marvel. For instance, enjambing that 5th line in order to set up a beat on the rhyme between “up” and “sup” — since “supper” swallows the sound with that purling “per”. The way “we love it is” dangles in the center, detached, quasi-cosmic, supernal and yet simply grounded by the monosyllables. And no period to punctuate the ending of this single-stanza skyscraper. Schuyler certainly wasn’t shy at punctuating his poems with periods. To me, all of his periods are audible, indicative of pauses between steps, like the hollow sound that rises from the ground when someone is pacing and the foot hovers above the floorboards. There is an expectancy of sorts to his pauses, and you can hear it in “Sleep” . . .

SLEEP

The friends who come to see you

and the friends who don’t.

The weather in the window.

A pierced ear.

The mounting tension and the spasm.

A paper-lace doily on a small plate.

Tangerines.

A day in February: heart-

shaped cookies on St. Valentine’s.

Like Christopher, a discarded saint.

A tough woman with black hair.

”I got to set my wig straight.”

A gold and silver day begins to wane.

A crescent moon.

Ice on the window.

Give my love to, oh, anybody.

I cherish this final line with the mute intensity reserved for unexpected sunshine opening in the middle of a thunderstorm — all those “o”s bumping into each other and trying to disentangle themselves from the forward motion of the declarative command: “Give my love to, oh, anybody.” Noting, too, the way “body” alters how the poem’s mouth closes— not with the matching “o” of “anyone” (that could so easily attach itself to “love” and thus vanish in the self-same sounding) but with the gallop of any-bod-ee, and the bump of that d.

Schuyler played with forms of address; he appreciated Frank O’Hara’s roving interlocutions that alternated between moving like arrows and bouncing like plastic balls at a fun fair, seeking a willing conspirator. This friskiness comes out in “Address,” where an ancient appears as an apogee.

ADDRESS

Right hand graced with writing,

my left arm my secondhand new

suit bestrode, from the auto I

say, “Antinous, perched like a

parakeet cracking sunflower seeds

in a hot ice cave or cage,

you’re an apogee. Acid pennies

will fill your mouth, your head

bowl at a soldiers’ revel. Fly

the safety you despise and seek,

a butcher with a butcher’s knife

peers. The lice are fast. Ta ta.”

One can even imagine some of these words coming from a list of A-words in the poet’s notebook. Address; Antinous; apogee; acid; and that final “ta, ta” — a bit of badinage that culminates in “ah”s. . .

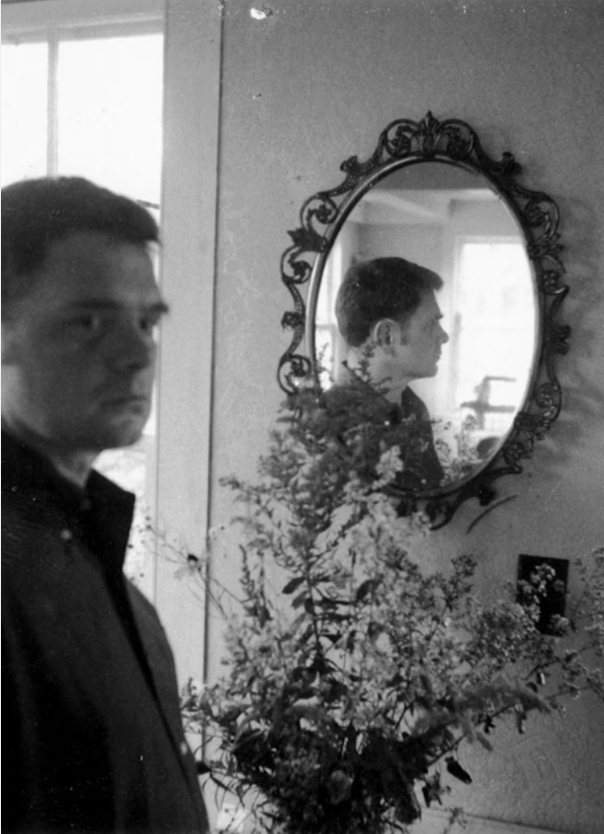

Photo of James Schuyler taken by Joe Brainard, sourced from the The Estate of Joe Brainard.

THE TRASH BOOK

for Joe Brainard

Though I do not know what

to past next in the

Trash Book: grass, pretending

to be a smear maybe or

that stump there that knows

now it will never grow

up to be some pencils or

a yacht even. A piece of

voice saying (it sounds like)

the hum that hangs in only

my left ear. Or “Beer” not

beer, all wet, the quiver

of the word one night in

1942 looking at a cardboard

girl sitting on a moon in

West Virginia. She smiled

and sipped her Miller’s.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse), c. 1896-1908

OVERTAKELESSNESS

after Albert Pinkham Ryder

To speak inaudibly, the outside,

its blurred sentence foreshadowed,

indistinguishable as shining brass.

The room, empty sky, beautiful

or golden bands burn because it is empty.

Without depth of field birds become primitive again.

Unstuck weeds float downstream

completing representation.

A thick green complicating light.

Now face the horizon is silence.

Come down while gladness unbinds sleep

unlike silt. This quiet speech feels right

and will be imitated. To turn away,

to speak fondly without a history.

Come down and rediscover this ancient province

as persons exchange smiles like wind instruments.

There, unlike any road you travel,

are small tidings that awakening,

are pleasing. No history is clear.

(If you hear Schuyler dialoguing with Ashbery, your nose is excellent.) Towards the end of his life, artist Arthur Pinkham Ryder lost interest in exhibiting his art and was said to live “in a decrepit home coated in dust, the floors littered with unwashed dinner plates, and obsessively reworked his existing paintings.” In my imagination, to rework a piece obsessively summons something of Schuyler’s title, that loosely-coined word, “overtakelessness.”

”When I say the ghost has begun / you understand what is being said,” Schuyler says in the first lines of “True Discourse on Power.” Compare the loquaciousness of this poem to the sparsity of “A Ghosting Floral”.

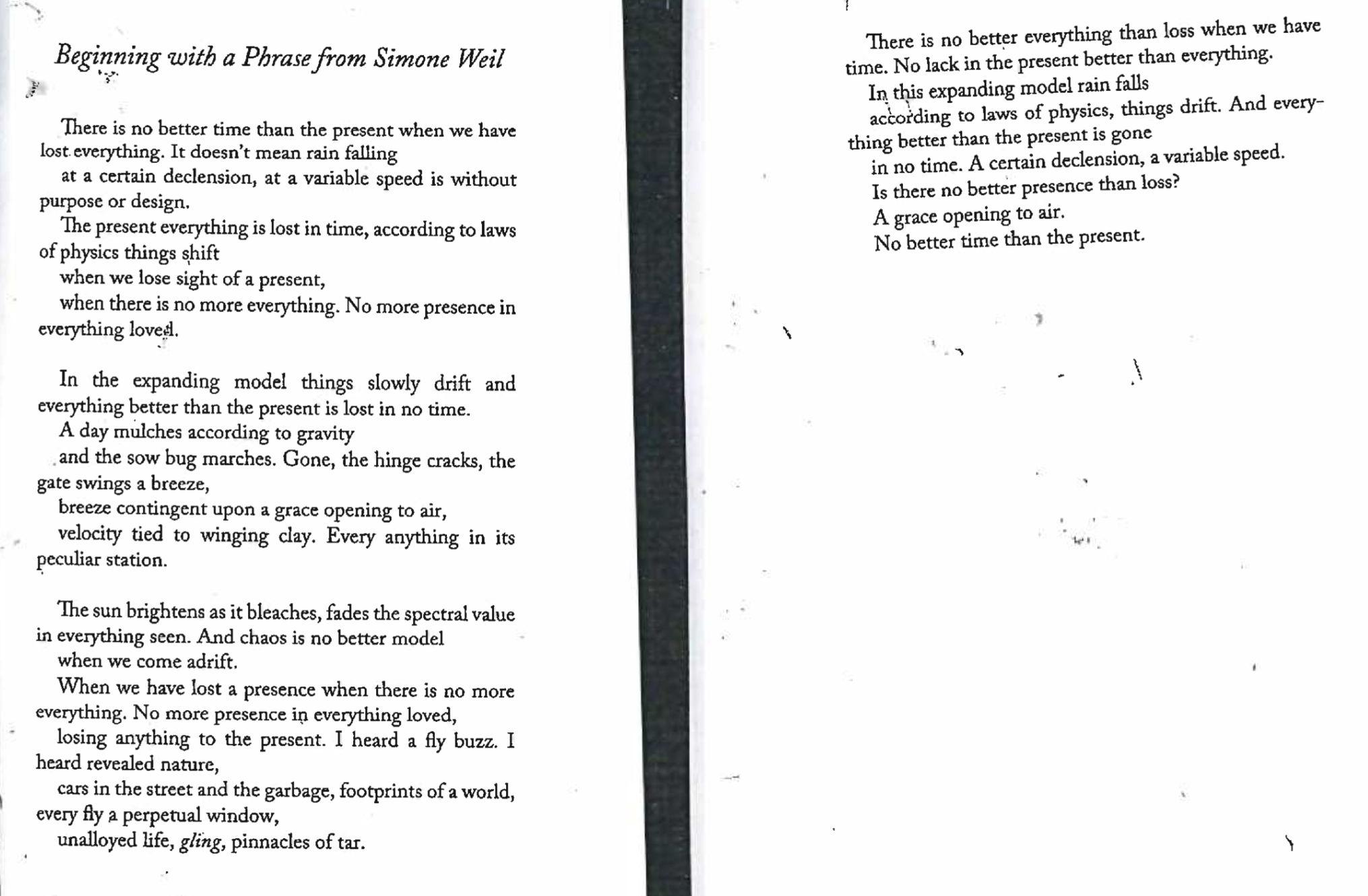

Schuyler also wrote many poems with lengthier lines, and “Revival” (a poem dedicated to Gregory Corso) is one of them. “It’s good to not break in America,” the poet tells his friend. Lament and comraderie is the backdrop, and that surface is also recognizable in “Beginning with a Phrase from Simone Weil”:

THE PRESENT IS CONSTANT ELEGY

Those years when I was alive, I lived the era of the fast car.

There were silhouettes in gold and royal blue, a half-light

in tire marks across a field — Times when the hollyhocks

spoke.

There were weeds in a hopescape as in a painted back-

drop there is also a face.

And then I found myself when the poem wanted me in

pain writing this.

The sky was always there but useless— And what of the

blue phlox, onstage and morphing.

Chance blossoms so quickly, it’s a wonder we recognize

anything, wanting one love to walk out of the ground.

Passion comes from a difficult world — I’m sick of twi-

light, when the light is crushed, time unravels its string.

Along the way I discovered a voice, a sun-stroked path

choked with light, a ray already blown.

Look at the world, its veil.

. . . And a little Schuyler cento for the moon in West Virginia—