How sad it is when a luxurious imagination is obliged in self defense to deaden its delicacy in vulgarity, and riot in things attainable that it may not have leisure to go mad after things that are not?

— John Keats, 7 July 1818

Freud said one of the reasons we laugh at jokes is because we need to experience again and again hiding and finding. Our love of being fooled is a vital need to recover first recognitions, to make if only for a moment our recognition innocent.

— Dean Young, The Art of Recklessness

Berlin. December 8, 1894. It is the secret of love that man and woman can never completely understand each other and therefore the desire persists.

— Harry Kessler, Journey to the Abyss

And wild is the wind

— David Bowie

[Poem in image above comes from Christian Morgenstern’s The Gallows Songs, a fantastic collection that revisits the 15th century ballades and forms fashioned by the French poet-troubadour Francois Villon, particularly his immortal Ballade des pendus.]

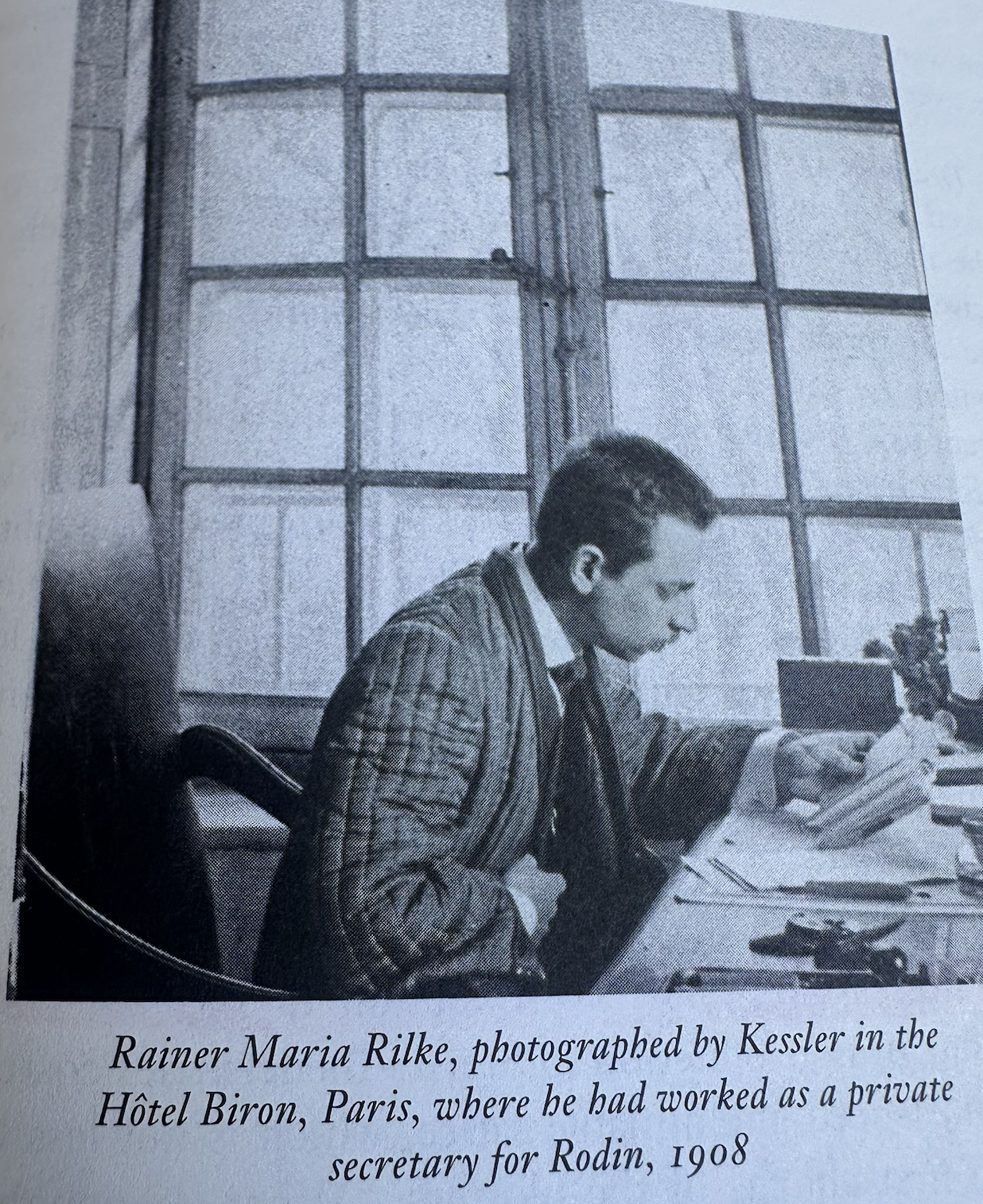

Count Harry Kessler knew everyone in early 19th century Europe— and we have his diaries to evidence it. I’ve excerpted his entries on Rainer Maria Rilke from 1907 to 1909; Rilke grapples with the role of relationships and families for the writer. He critiques the way Rodin made use of women rather than apprehending them as autonomous persons, artists, humans. Certainly I could raise a large mirror to Rilke here, if I had time, but I leave that to my betters and share, instead, these journal entries from Kessler, who also became Rilke’s correspondent in letters.

Bremen. December 21, 1907. Saturday.

In the evening the Rilkes came to dinner. She [presumably Clara Westoff] has something great and simple, willful, almost masculine. He appears to be the more feminine of the two. When he sits, while speaking, crunched up in his chair, his legs and arms crossed, you get the impression from his thin body and his soft voice, that sounds as if it were pleading, of an ugly young girl. He spoke of Prague, Russia, Paris, always in quite long, soft, somewhat precious sentences. He goes only unwillingly to Prague. For him it's still too reminiscent of a very confused childhood, in which the mystery of the great palaces, the strange, old princesses or young countesses who disappeared in their coaches through the briefly opened gates of great courtyards, heightened by the fact that the lower classes in this city spoke a tongue he didn't understand and even was not permitted to understand. In his parents' house the servants had been Czech, but this fact was ignored as much as possible and the children were only permitted to speak a pair of the most unavoidable words for making themselves understood.

And yet he had had already a half-unconscious but deep sympathy for the Slavic. He only came to a clear awareness of this sympathy when he accompanied, completely unprepared, a friend on a trip to Moscow. “When I awoke in the morning in the large hotel, I suddenly felt: This is my home! I had always felt homeless and had never really believed that I would find a home anywhere. But suddenly everything here made sense. The feeling may have been strengthened by the fact that my window was across from the entrance to the Kremlin, exactly opposite a small chapel into which one could see from my window. Everything in it was completely silvery, with silvery icons, before which eternal flames burned night and day. Pilgrims came constantly and fell on their knees, and the carriages, racing at a gallop through the streets, always stopped for a moment so that a gentleman or some high officer would jump out, cross himself, and then depart again at a full gallop. There was such a connection between the primeval and the completely modern, between mysticism and the life of a large commercial city, that I was deeply moved. On that trip I only visited Moscow. Later I traveled through Russia for three-quarters of a year everywhere: in cities, in villages, on estates in the country. I traveled the entire length of the upper Volga then. And confirmed what I had felt the first time, the deep connection between these things and something in myself.”

I asked Rilke about Paris, how his deep relation to Paris related to his love for Russia.

Rilke: “That's something completely different. Paris is for me a school. I learn so much there. I departed from nature and have always felt things very deeply, almost too deeply. But, however that may be, I was less interested in people. People always seemed to me to be too confused inwardly. But in Paris it is as if every single person has a clearly recognizable voice, expressing his inward being. The people there are like birds. You listen and say to yourself, Aha, that is the voice of this bird who wants this, and this is the voice of a different bird who wants this other thing. When I first came to Paris it was only because of Rodin. I rode out every day to Meudon and concentrated entirely on my task, my book. But when I finished the book, I became aware suddenly that along the way, without noticing, I had absorbed all these other impressions and now they were coming to the fore and with such force and so painfully that I suddenly couldn't stand it any longer and fled in a hurry to a small part of Italy where I had retired several times before when the outer impressions had become too strong. My only thought was, 'Never go back to Paris.' But then it wouldn't let me go. I said to myself, 'I must try again and see if I can stand it.' And when I arrived the second time I was able to stand it and now I never work so much as in Paris. Paris is for me a school, which teaches me to endure what is frightful and heart-wrenching about modern life because people there are so sharply delineated from each other. There is so little confusion. The beggar on the street is just a beggar and nothing else, and the street boy and the old maid. With us a beggar is ashamed to be a beggar.”

Paris. October 12, 1909. Tuesday.

Visited Rilke in the afternoon in his beautiful, princely rooms in the Hotel de Biron, next to Rodin. Through the large casement windows you saw the garden in the autumn light. Rilke sat there, weak and shivering, despite the warm autumn sun. He wants to give these rooms up. They have collected so many sad memories for him, he's been sick in them so often, and so often unable to work, that now it's as if spider webs covered him. The previous winter here was so bad for him, in part physically, in part psychically. So many things that he thought he knew had shown him another side that his entire world had been rocked, so to speak.

As one of the things that changed for him, he named Rodin.

I: “In what way?”

Rilke: “Yes, so much that I had thought to have discovered in him proved to be false. I see so much now about him in a completely different light.”

I: “His art?”

Rilke: “Yes, even his art.”

I: “So, his life?”

Rilke: “Yes, things in his life. You see, when I was around him so much several years ago, then he seemed to me to be a living example for how an artist growing old could be beautiful. I knew that, or believed to know it, from the example of Leonardo, Titian, etc., but Rodin for me was the living proof. I said to myself, So I too would like to become old in beauty. And then it suddenly turned out that growing old is something terrible for him, exactly as terrible as for your average person. He is bored. Now when he cannot fill his entire dow with his enormous works, he's bored. One day he came here to me in the studio and said to me, 'I am bored.' And how he said it, I saw how he observed me, how he peeked secretly – almost frightened—to see what kind of impression this confession would make on me. He was bored and seemed not to be able to understand it himself. And this boredom had something frightening, because now, due to it, other things became important for him, which up to then had vanished before his enormous appetite for work. And he took these things, not as one would expect from Rodin, but exactly as one would expect from any other old Frenchman.”

I: “The women?”

Rilke: “Yes, the women and other things as well, which I had always assumed he had somehow taken care of in his life a long time ago, given them a certain fixed place. Now it suddenly turned out that he had not even thought about these things before. So he came running to me here one day, seized by a nameless fear of death. Death, he had never even thought of death! Things that I had assumed he had made his peace with thirty years ago have now seized him for the first time, when he's old and no longer has the energy to be rid of them. And so he looked to me, the young person, for help with his nameless fear of the idea of death! Some years ago it was still different. The first time he spoke to me about death was in Meudon. We stood leaning on a balustrade and looking at the valley below. Then he said he couldn't grasp it that now when he had finally learned how to work, that this work would suddenly stop one day. That didn't seem possible to him. Then it was still the sorrow for his work that must be interrupted, so something noble, that moved him. Now, however, it is the pale, naked fear of death, without anything consoling about it. His entire immense work, in which he, as I believed, had come to terms with all things, now represents just the opposite, an obstacle, something that leaves him no time to think seriously about these things, about death, about women, without the time to find some kind of firm relation to sensuality. These things so overwhelm him now when he can no longer work so hard, when he suddenly has free time, and so everything has become for him a horror.”

Paris. November 16, 1908. Monday.

Visited Rilke, who lives in the Sacré-Coeur cloister, the former Biron Palace, 77, rue de Varennes. He has a tall, round corner room on the ground floor, looking out toward the garden, where he works, and next to it, or, more precisely, in front of it, for you walk through this room, his bedroom.

In its somewhat majestic elegance and isolation the study is a space in which you can imagine Hofmannsthal's Death and the Fool. Rilke has a few Empire chairs and a large old baroque table set up as his desk. Some consoles as well, upon which beautiful ripe fruits and flowers are placed. A bust of his wife stands in front of the garden window. Otherwise everything is empty, but not cold because of the beautiful proportions and light.

He read to me his requiem for Wolf Kalckreuth. While reading his profile was outlined against the mighty baroque window and I noticed for the first time the energy in his traits. A very curious profile: the long slanting forehead, the long slanting nose, almost in a line with the forehead, both springing forward like a beak, and then, almost in contrast to this sharp line, the heavy thick lips, the heavy eyelids. He reads somewhat like a pastor but with a clearly defined pronunciation. In conversation afterward he spoke repeatedly of his "writing poetry according to nature."

Rodin said to him, "Why don't you sit before the landscape and do what you see?" I asked him what he meant with this "writing poetry according to nature."

He: To write into things instead of away from them. Not to latch onto some— perhaps only fleeting – impression in order to attach feelings or observations so that the poem would arise out of the beautiful beginning, but rather to amalgamate the feeling with the things themselves, to fill them with it, so to speak.

Ever since he has forced himself to do this, a new epoch has begun for him. At first he thought he would never learn it. But he felt that now it's either bend or break, and he broke through. Now he's gone so far that it's easy for him to "write according to nature."

*

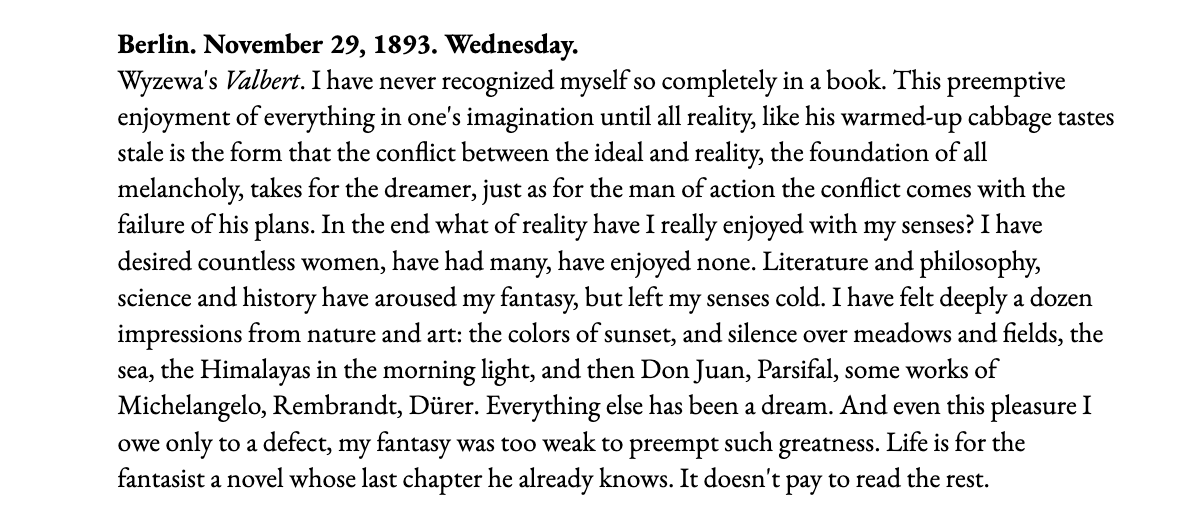

Leaving Rilke in the margins for a moment, there is one particular diary entry that made me love Harry Kessler, or at the very least, begin to fathom why he collected art and kept notebooks. I share the entry in full below, for the spark of recognition that occurs early in a man’s life, and gives rise to Montano’s malady:

"... what pleasure wants is the site of a loss, the seam, the cut, the deflation, the dissolve which seizes the subject in the midst of bliss.”

– Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text

“I don't believe in perfection or perfectibility (although the shark sure comes close).”

— Dean Young, The Art of Recklessness

*

An earlier version of Kessler’s diaries was published as Berlin In Lights, and introduced by Ian Buruma. For more on Kessler and his multivariate life . . .

Alex Ross, “Diary of an Aesthete,” New Yorker, April 23, 2012.

Jonathan Steinberg, “The Man Who Knew Everybody,” London Review of Books, 23 May 2013.

Peter Gay, “The Right Man to Keep a Diary,” New York Times, August 22, 1971.

”Dined with the Einsteins,” The Diary Review, November 30, 2017.