They are, it seems, savage and impenetrable, black and russet, extravagant, secular, swarming, diametrical, negligent, ferocious, fervent, and likeable, without yesterday or tomorrow. . . . Naked, they dress only in their majesty and their mystery.

— Max Ernst on the forests of Oceania (t. by E. Childs)

Frotter, meaning “to rub.”

Ernst’s first frottage, Animal, emerged from rubbing a pencil over the back of a telegram. But frottages didn’t become a systematic part of his work until he executed the Histoire Naturelle series in 1925. This conception of frottage as an archeological practice that creates art/efacts reminds me of rubbing lead over white paper in graveyards, back in the days when I collected epitaphs from tombstones and grave markers. There is a relational aspect to this rubbing— a sort of effort to rub life up from the traces, or to create an image that can’t resist its eternity.

The uneveness of a surface is what makes frottage possible. The lead picks up the traces of dips and blips. I always thought of radio waves as I did it. In a sense, frottage is all about riding the glitch and agreeing to dabble in the hauntological.

Frottage, the art of rubbing an uneven surface for relief.

And how Max Ernst described it:

Ernst’s first frottages came from an interest in grain. He dropped pieces of paper at random on floor boards and rubbed them with pencil or chalk, thus transferring the design of the wood grain to the paper.

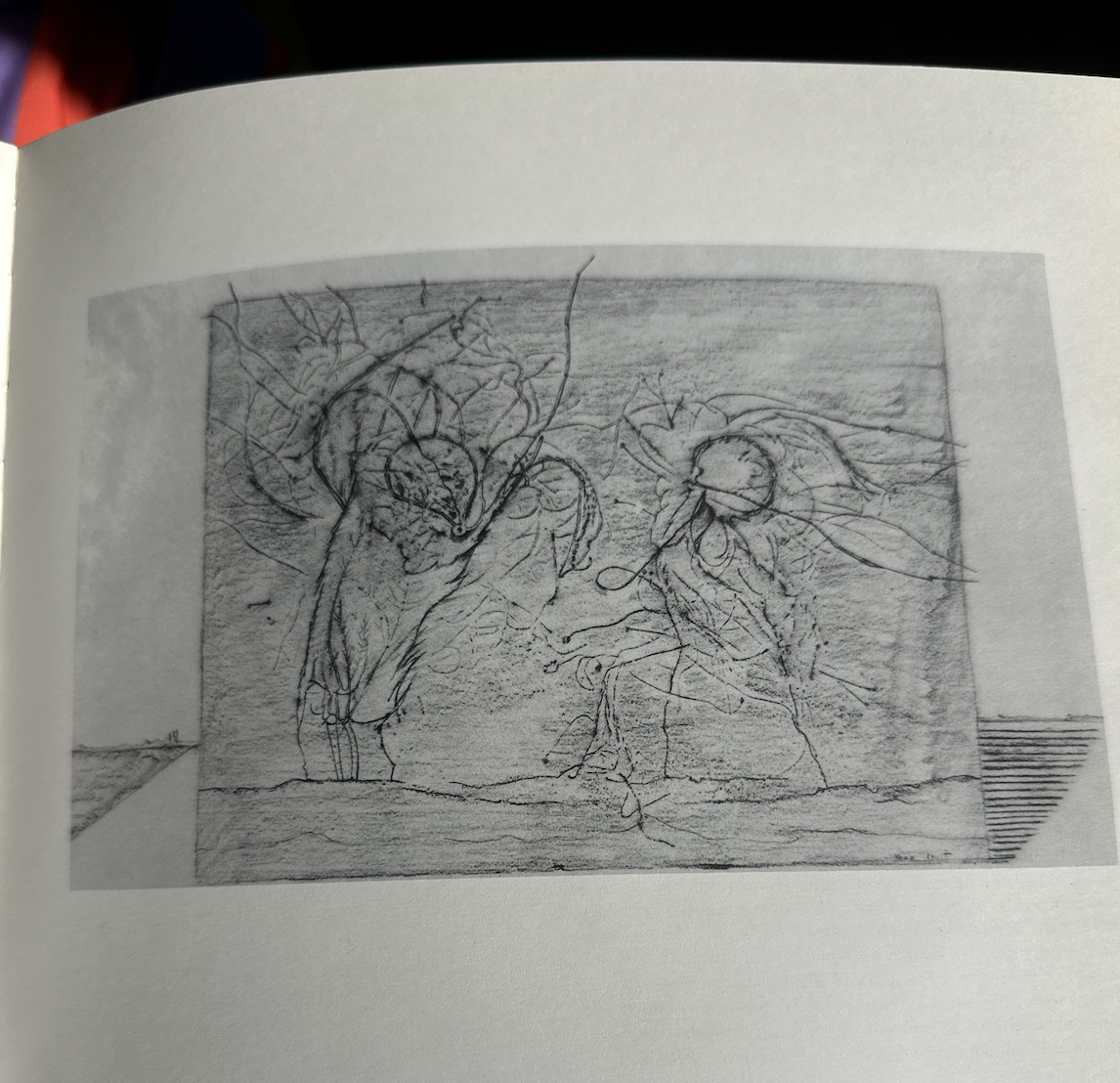

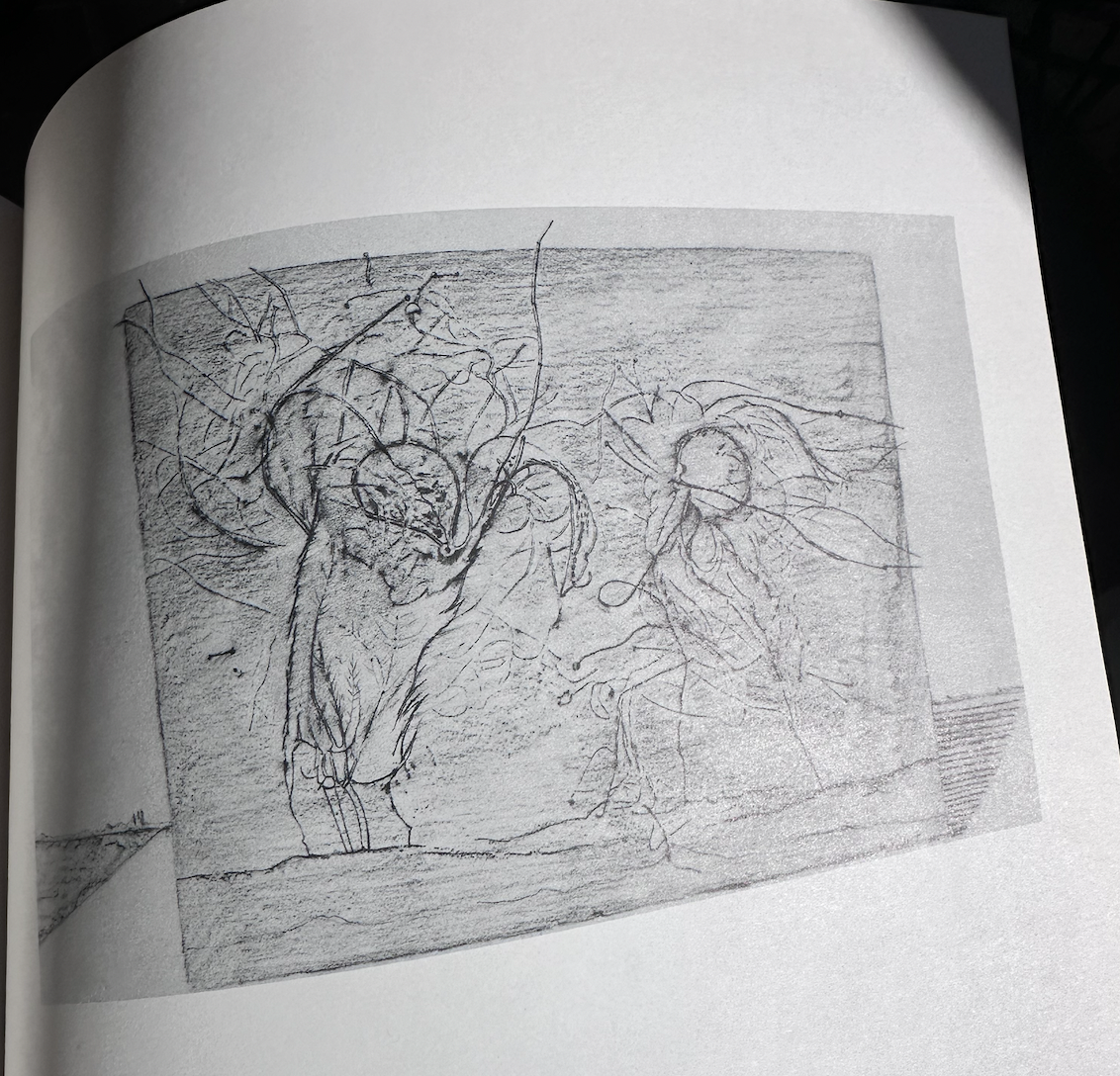

Max Ernest, Les coups de fouet ou ficelles de lave (1025)

Number 11 from Ernst’s Natural History series is titled Les coups de fouet ou ficelles de lave (“Whip lashes or lava threads”). It has enchanted me through this vicious little migraine that perches above my right eye and tries to punish every glimmering light ray. I forgive even the migraine for the sake of Ernst’s whip lashes and lava threads.

*

According to Elizabeth Childs, Ernst adapted his frottage technique to oil painting by “scraping paint from prepared canvases laid over materials such as wire mesh, chair caning, leaves, buttons, or twine. His repertory of objects closely parallels that used by Man Ray in his experiments with Rayograms during the same period. Using his grattage (scraping) technique, Ernst covered his canvases completely with pattern and then interpreted the images that emerged, thus allowing texture to suggest composition in a spontaneous fashion.”

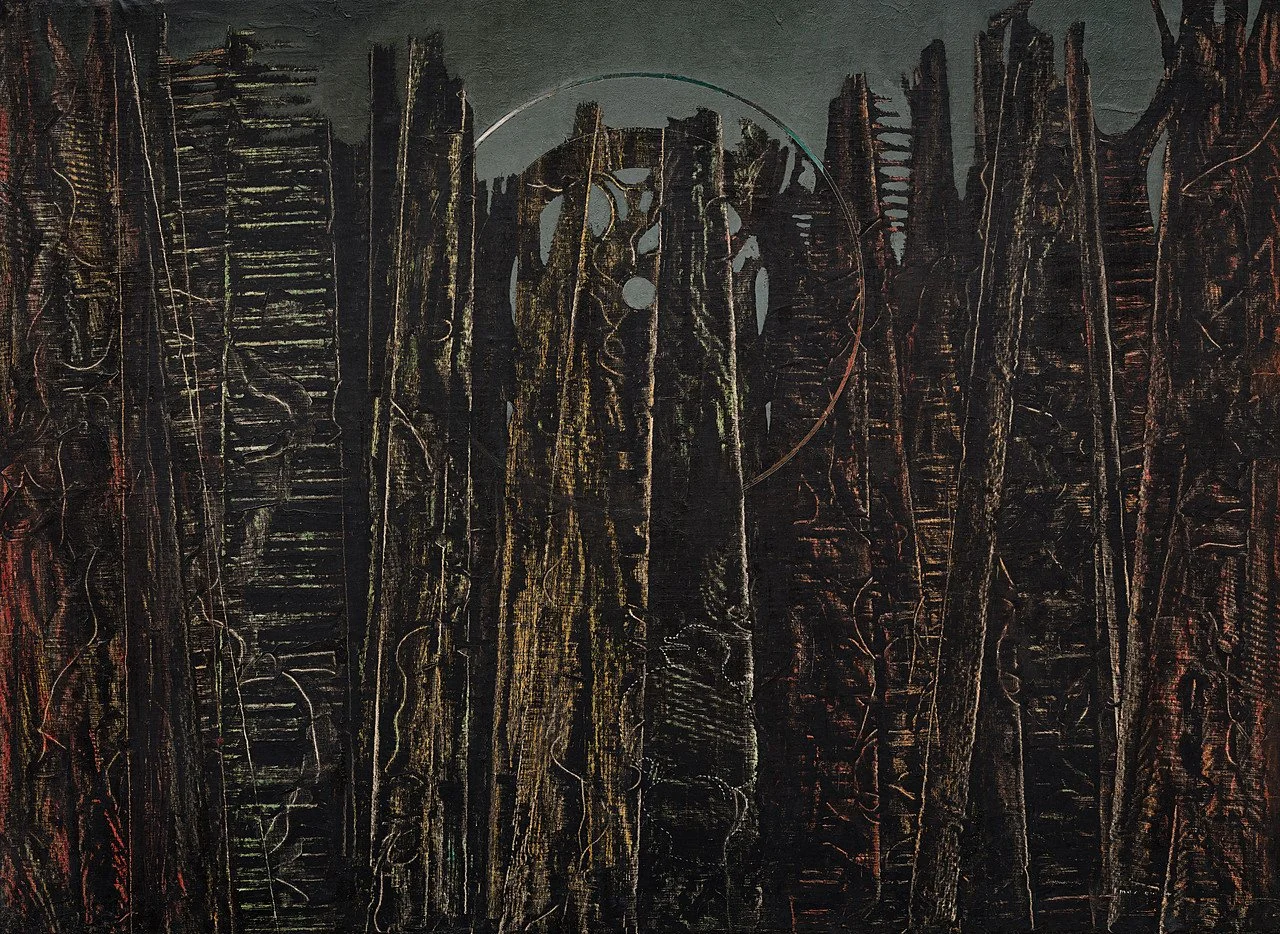

Childs suggests that theThe Forest was likely created when Ernst placed the canvas “over a rough surface (perhaps wood), scraped oil paint over the canvas, and then rubbed, scraped, and overpainted the area of the trees.” He returned to these dense, eerie forests as subjects throughout the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, including theThe Quiet Forest (1927), presenting the viewer with “a wall of trees, a solar disk, and an apparition of a bird hovering amid the foliage.”

“Ernst’s attitude toward the forest as the sublime embodiment of both enchantment and terror can be traced to his experiences in the German forest as a child,” says Childs, foraging his essay “Les Mystères de la forêt,” published in Minotaure in 1934, for the artist’s intrigue with forests and trees.

*

Making animals with Max Ernst (a rubbing activity from MOMA)

Max Ernst, The Fugitive (L’Évadé), 1926

Max Ernst, The Forest (La forêt), 1927-1928

“Max Ernst and His Experimental Art Techniques” (Max Ernst Museum)

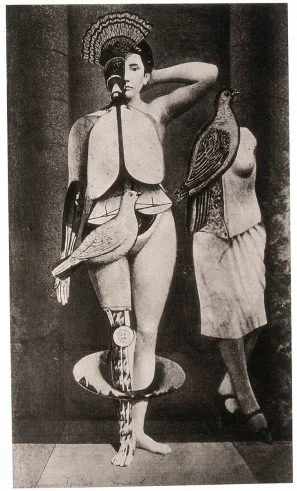

Max Ernst, Sacra Conversazione, 1921. Photography of a collage. (Source)