Only fiction will accommodate the facts of life...Our choice, insofar as we have one, is not between fiction and fact, but between good and bad fiction…If it's a matter of words, if it's a function of language, if it's concerned with what it's like or not like to be human, it will prove to be some sort of fiction.

—Wright Morris, Time Pieces

1

In 1977, Philip Guston read an essay that changed how he understood his art’s relationship to allegory. This classic Benjaminian moment was described by Guston’s close friend, Ross Feld, one of the three men that the painter selected to perform his posthumous kaddish. Feld admits that “Philip Guston had a nearly limitless appetite for talk.” Their friendship blooms from this loquaciousness:

Once, when I visited him upstate, the first words out of his mouth as he met me on the train platform at Rhinecliff were: “So—about Brancusi..” It wasn't surprising, then, to hear him begin telling me one day over lunch in the Village in 1977 about something he'd been reading a few days before that had excited him greatly. He'd read an essay by Charles Rosen that had appeared in The New York Review of Books, a piece that concerned Walter Benjamin's 1928 book, The Origins of German Tragic Drama. This had been Benjamin's first and only completed longer work, his doctoral thesis (though rejected); and Rosen's discussion of one of Benjamin's signature ideas there—the notion of art as ruin— seemed to have enveloped Guston in a blaze of sparks.

The enthusiasm, coming from a painter whose father had for a time peddled junk— and who himself for forty years had been picturing garbage cans, middens, old pots, and crumbling walls—was understandable. Yet on that 1977 midday Guston seemed to me unusually wound up. His talk leapfrogged here and there. When we hadn't seen each other for a few weeks I tended to be more conversationally correct, spending some time tugging Guston back to earth a little when his kite seemed headed for a tree. But this idea of art as finished not only in a practical, immediate sense but in an elongatedly temporal sense—as something dead and in its very essence decaying—was something Guston clearly responded to on the deepest level, and there was no stopping him.

Not that many months later Guston would bring up Benjamin again, this time at a public “discussion” the two of us had together at Boston University. Guston was a University Professor there during the seventies [...]

After noting the “schmoozing” that characterizes this event, Feld tells us that Guston kept drawing the panel discussion back to Benjamin’s book on the Trauerspiel. “Not fifteen minutes into it, Guston again was back on the Benjamin book, this time recommending as ‘very very interesting’ Benjamin’s analysis of Baroque allegory as outlined in the Roten essay,” Feld noted:

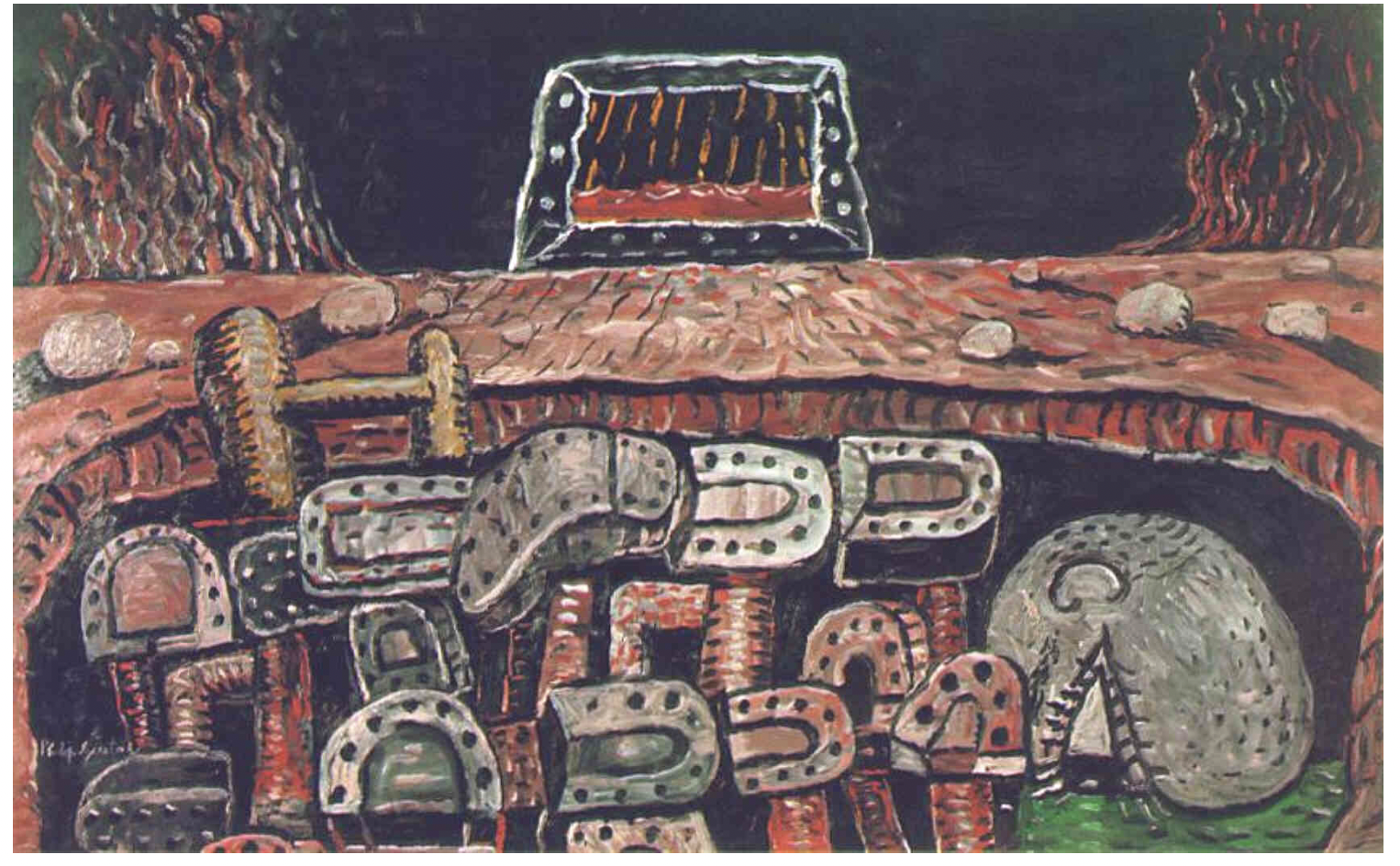

Guston then went on to refer to his own current paintings as allegories, which made me cringe a little. An unusually articulate man, he was hardly someone to use words he didn't mean—-but Allegory? So trampositional. So obvious. Besides, modernity had effectively neutered the whole category. Guston patiently granted that allegory was, yes, all that, modern and certainly obvious. But then, with a small mischievous smile, he said: “That's why I think I like the whole idea.” And more than simply liking it, he reminded me, he also had lately gone ahead and happily used the armature. For what else would I call a painting such as one he'd done a year before, Pit (1976) — a sulfurous sinkhole in Hades abrim with the heads of the grossly (and yet somehow happily) damned – other than an allegory?

I still wasn't convinced. Neither was Joseph Ablow, who was in the audience that night. Between us we came up with lots of reasons why allegory was merely a curiosity, why Guston's interest in the subject was somewhat perverse. Guston was good-naturedly unmoved by all of this. “Well, I still think I'm making allegories.”

2

We spent 8 hours in the car over the past 24 hours, only one of these hours involving any shard of sunlight. I tried to catch up on my reading. Heaven forbid there should be allegory at work in any of this.

3

Ben Lerner describes one of his dreams involving Keith Waldrop. In this dream, Ben is an undergrad “trying to impress Keith by saying something about Olson’s ‘Projective Verse.’ When I finish my little speech Keith is quiet for a moment and then says: “It’s always seemed to me that lines of poetry are broken less by the way a poet breathes than by the way a poet blinks his eyes.”

4

Excerpts from Philip Guston’s letter to Ross Feld, dated September 1978:

Sunday-Sept. '78

Thoughts (or Advice to myself)

Ross,— So it is truly a bitter comedy that is being played out now—A ‘Painting’ which is like ‘real’ life—as it is lived from hour to hour, day to day, cannot be a picture! It is an impossibility! Feelings change—keep shifting— it is a fantasy the mind makes, the attempt to fix—it could be like accepting a dogma of some kind— of belief. But it won't stay still—remains docile. One cannot tame anything into docility with oneself as the master—be a lion tamer?—that is razzle-dazzle, that's circus. Fool the eye.

Sometimes I spread out all over the canvas, the rectangle of action, and try to fix—make the momentary ‘balance & unbalance’ into a form that I can look at— ‘live with’ —and because of its very instability and precarious condition I can. I did this last week. Now, this week, in reverse, I made a huge & TOWERING vast rock with platforms—ledges, for my forms to be on—and to play out their private drama. A Theater— maybe? A STAGE?

This will remain for a while—this series.— Of course they needed platforms— steps—to act it out. But then the rock itself became precarious, shaky and wouldn't stay still-it, too, participates in the changing instability of everything. So even when I want & need to make something solid-just there—like a Pyramid—it starts shaking and the whole thing—-the rock as well as the forms are swarming– moving in all directions at once— As if there were ne possibility of any kind of order— that we know of, or have seen before. If we are weak, we distrust it?

So, if things are moving, changing so rapidly, it is folly to hold—to fix—Yet the attempt must exist—& be made. Why?

If I think of the forms as on a surface, on a flat plane—if I give in to the limitations of the plane, its restrictions, and accept its orders, OBEY, and follow through to a fixation, one inevitably ends with a ‘nothing’—an emptiness, which is similar, I think, to the flatness of a belief. A PURITY. This is a fantasy I cannot believe in, for I then become tedious and boring to myself-reminding myself, remembering what I thought or felt yesterday, what the rules are, or were— Here is where it all tumbles and collapses! The image then becomes ‘a picture’ —a sign—an icon—and even though it can be a "significant" and deeply felt "nothing" (OR A THOUGHT) it does soon pall.

[...]

What, then, is there to do—where, then, is there to move?

Only the most feared is left. To create a living thing— as it lives–and to see it! Impossible! (It is somehow evil to make a Golem, but to make a living ‘thing?’) That is a far greater evil —(also ‘unnecessary’). So, to abandon yourself to the unknown of the doing— is all that's left, only the reflection of the passing of time—-but sharply visible made so– as this act of making is lived out.— And— then you move into the next, like a strange and new clock, warping Time into becoming a frightening new other place, a land in which there is no rock and no ‘nothing.’ What is there– then? There is only the next doing which leads only to the next doing. A lifetime of doing?

Nerves. The nervousness of the maker is what one has—very little else—— and even the "else" is rancid, —like old G dried seaweed clinging on.

Advice to myself —

Do not make laws.

Do not form habits.

You do not possess a way.

You do not possess a style.

You have nothing finally but some ‘mysterious’ urge—to use the stuff—-the matter.

5

“The scenery, when it is truly seen, reacts on the life of the seer. How to live. How to get the most life. How to extract its honey from the flower of the world.”

These four sentences were written by Henry David Thoreau long ago.

“This is the religious equivalent of that, especially in music and applied fields, long meadows,” wrote Ben Lerner in “The Media” — which happened to be published in the New Yorker on my birthday a few years ago.

6

Livened by Feld’s depiction of Guston’s reckless relationship to the act of creation, my mind wandered back to passage by Helen Vendler, a passage about poetics which parses Wallace Stevens’ formal feelings within his inchoate hungers:

Since feeling— to use Wordsworthian terms— is the organizing principle of poetry (both narratively, insofar as poetry is a history of feeling, and structurally, insofar as poetry is a science or analysis of feeling), without feeling the world of the poet is a chaos. As we know, as the poet knows, the absence of feeling is itself—since the poet is still alive— a mask for feelings too powerful to make themselves felt: these manifest themselves in this poem (“Chaos in Motion and Not in Motion”) as that paradoxical ‘desire without an object of desire,’ libido unfocused and therefore churning in all directions— like a wind, as the last line of the poem says, ‘that lashes at everything at once.’ Unfocused and chaotic libido does not provide a channel along which thought can move. Once there is an object of desire, the mind can exert all its familiar diversions— decoration, analysis, speculation, fantasy, drama, and so on. But with no beloved object, the mind is at a loss; the hero of the poem has ‘lost the whole in which he was contained.../ He knows he has nothing more to think about!’ The landscape is the objective correlative to this state of mind: ‘There is lightning and the thickest thunder.’

There is also Guston’s The Line, painted in 1978, the year flush with correspondence between himself and Ross Feld. I love how the cloud resembles the frothy lace at the wrist of an 18th-century sleeve . . . . and how the line is drawn by the sun’s shadow rather than a finger in sand. It is as if Guston wished to work an oppositional idiom (contra ‘line in the sand’) and give us the lightning of a god whose stylus arrives by other means. I think this painting in particular demands that allegorical mode.

*

Ben Lerner, “I don’t want to go to Heaven, I want to go where Keith goes” (Poetry Project Newsletter, Summer 2023)

Helen Vendler, Poets Thinking: Words Chosen Out of Desire

Henning Kraggerund, La melancolie (arranged by H. Kraggerud for Razumovsky Symphony Orchestra)

Maurice Ravel, Miroirs: II. Oiseaux tristes (performed by André Laplante)

Philip Guston, The Pit (1976)

Philip Guston, Departure (1963)

Philip Guston, The Line (1978)

Ross Feld, Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston (NYRB Classics)