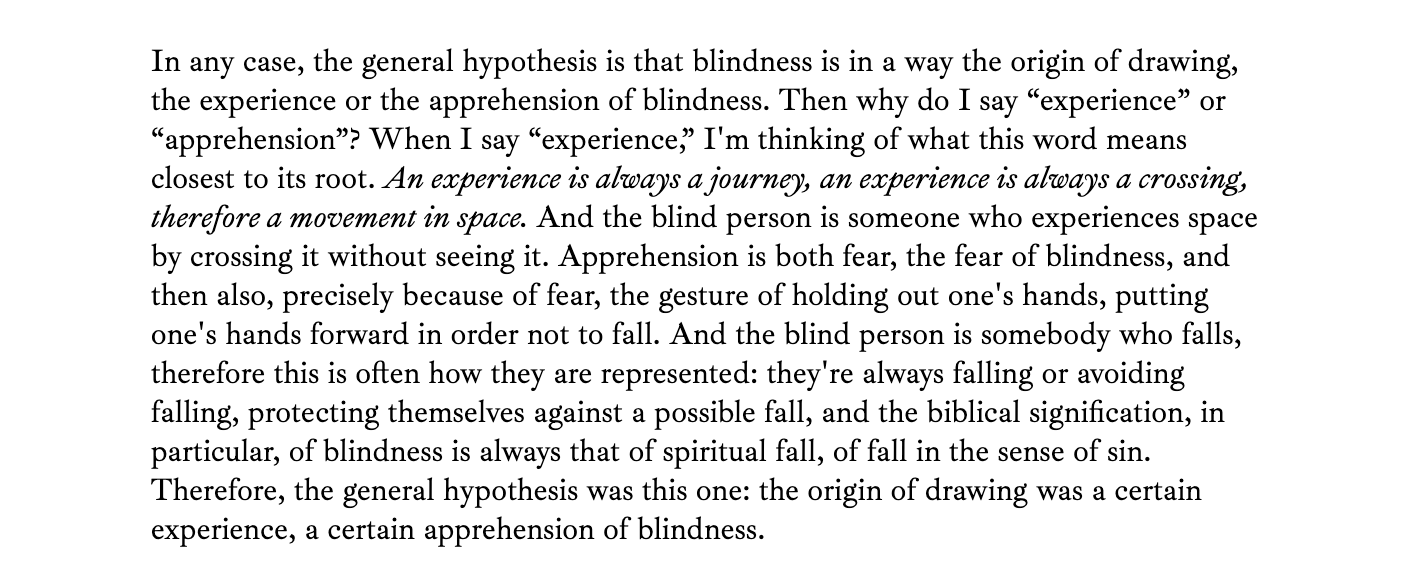

At extremes of human experience, the habitual reflective syntax of language breaks, just as reflective consciousness breaks, opening to the catastrophe of a present that recalls no precedent and anticipates no aftermath.

— Donald Revell, “Better Unsaid: On Poetic Fragments”

Last night, after texting back and forth with the teens about whether they would return before midnight— whether they should return before midnight —- whether midnight, itself, can be asked to stand for a line that my partner likes to call a “curfew” — whether boundaries make us safer or just protect us from imagining how one day’s feelings spill over into the next day’s not-quite light yet.

. . . No fear alone at night she’s sailing through the crowd . . . . .

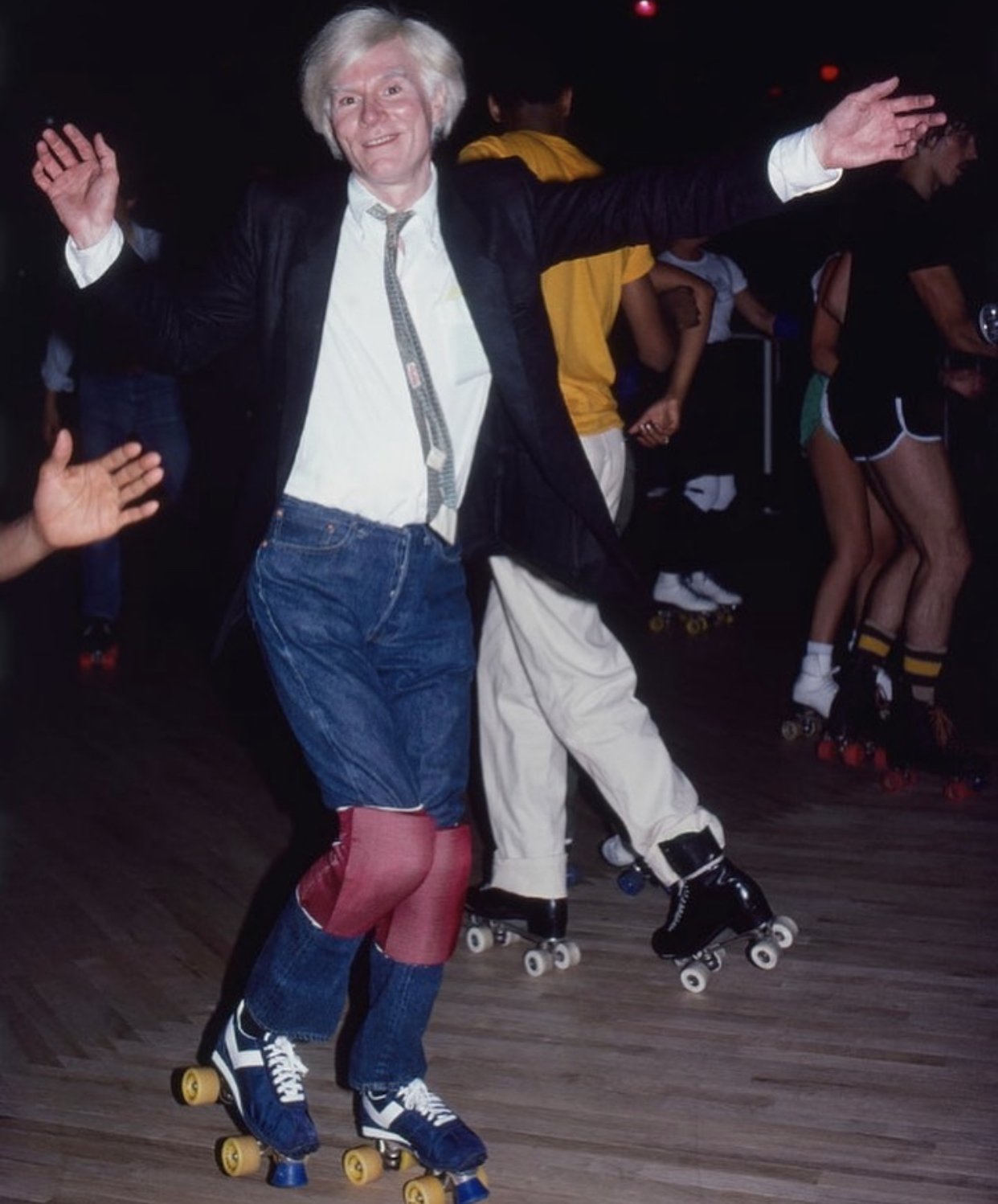

In 1980, The Dire Straits released their album, Making Movies. To this day, any bar from its rhymes drags my mind back to the age of 17, the signifiers and psychogeographies of that terrain. Whiplash. Skateaway careening from the kitchen speakers, calling me elsewhere, mid-text. The realistic mom-mask falls from the face. The tongue finds the fork in its path.

An intersection captions the crossroads:

“Your mom remembering what she was doing at 11 pm on a Friday night at your age.”

Hell, it’s an anthem for me. Why not read the corniness closely?

In this case, the unpacking must begin with the titular luggage. “Skateaway” is that particular form of neologism known as a portmanteau word. Beloved by Surrealists and OULIPO, portmanteau words erase the spatial gap between two words, in this case, cramming “skate” (a verb) and “away” (an adverb that modifies skate), rendering an action that also alludes to a state. Skateaway is given as a way of being precipitated by a certain type of action which the song’s subject— a girl on skates— creates.

Aside: One of my favorite portmanteau words, Barococo, or “excessively ornate in style,” combines baroque and rococo. Baroque is a borrowing from French that originates in the older Portuguese barroco or Spanish barrueco, “irregularly shaped pearl,” though linguists have also connected it to the Spanish berruca, “wart” (from Latin verrūca). Rococo is also borrowed from French and derives from Medieval Latin rocca, “rock,” which may come from a Celtic source or, alternatively, Latin rūpēs, “cliff.” In music, Barococo refers to a certain type of “impersonal” background music that originated in the Baroque and pre-Classic periods and was popularized in the early 20th century by technology that permitted longer-playing records and allowed listeners to demote music to ambiance rather than active listening.

“Skateaway” is recognizably Knopfleresque in its snappy refrain, guitar bridges, and extended guitar solo rounding out the end. The song opens with a view: the speaker sees a girl breaking the rules of traffic by skating against the flow. “I seen a girl on a one-way corridor / Stealing down a wrong-way street.” She is stealing, as he puts it, though we don’t know yet if this is an accusation or reason for admiration.

The misheard lyric is a convention of my listening practices. Accordingly, I spent most of my life believing the lyrics to be:

For all the world like an urban toreador

She had wings on, on her feet

when in fact the lyrics did not include wings, or any other allusion to flying. My wings are Knopfler’s wheels, which is a more sensible thing for a skater to have on her feet. The difference between wings and wheels is that the former has little connection to the ground while the latter allows one to move over the ground quickly. Wheels are eminently grounded.

The first allusion to dance comes with the cars: “Well, the cars do the usual dances / Same old cruise and the curbside crawl.” At this point, we have an “urban toreador” (an image I adore) inserted into a scene where cars are doing the sort of dance that has rules, conventions, an ordinary. The girl disrupts the dances doubly: first she disrupts them by going the wrong way, or breaking the rules, and then she disrupts them by jamming the familiar aesthetic with the provocation of bullfighting.

It is the ambivalence of the car’s drivers that creates excitement. Bullfighting is a bloodsport: one of the lives in the ring will end. But this tone of this song is light, frisky, ____ (ambi-valent). The cars are doing their usual dances “But the roller girl, she's taking chances” and “They just love to see her take them all.”

A breakdown of the song’s verse structure:

All the verses (stanzas) have 4 lines, excepting my favorite verse, which has 5 lines.

If your gander involves refrains, there are many ways to combine the verses and study what gets amplified (and maybe altered) through repetition. My gander doesn’t know what it wants, and proceeds accordingly.

Briefly, taking the verses as stanzas, we have the following structure (with no eye to end-rhyme): A / B / C / D / E / C / F / G / H / I / C / F / G / J / K, where C is the first refrain and G is (loosely, loosely) something like a second refrain.

The first refrain elucidates the affective conditions of the skateaway: headphones, night, crowds, city streets.

No fear alone at night

She's sailing through the crowd

In her ears the phones are tight

And the music's playing loud

The next verse is simply a casual exchange that sets the terms of communication between the speaker the girl: “Halle-LU-jah, here SHE comes / Queen ROLLerball / And ENchanté, what can I SAY? / Don't care at all.”

No pressure. No worries. She’s not looking for conversation or attention. If she gets it, she may laugh but she won’t stop skating, and skating is her purpose. The gaze (what they “love to see”) is part of the background scenery when you are moving too quickly to be apprehended by it. In a way, interpellation loses it power in the skateaway realm.

What’s different about the skateaway is that it puts an end to the waiting: “You know, she used to have to wait around.” She used to depend on things that came to her. “She used to be the lonely one.” Skateaway shifts agency. “But now that she can skate around town / She's the only, only one.” She can tell her own story rather than waiting to be told or defined by adults, parents, experts, priests . . .

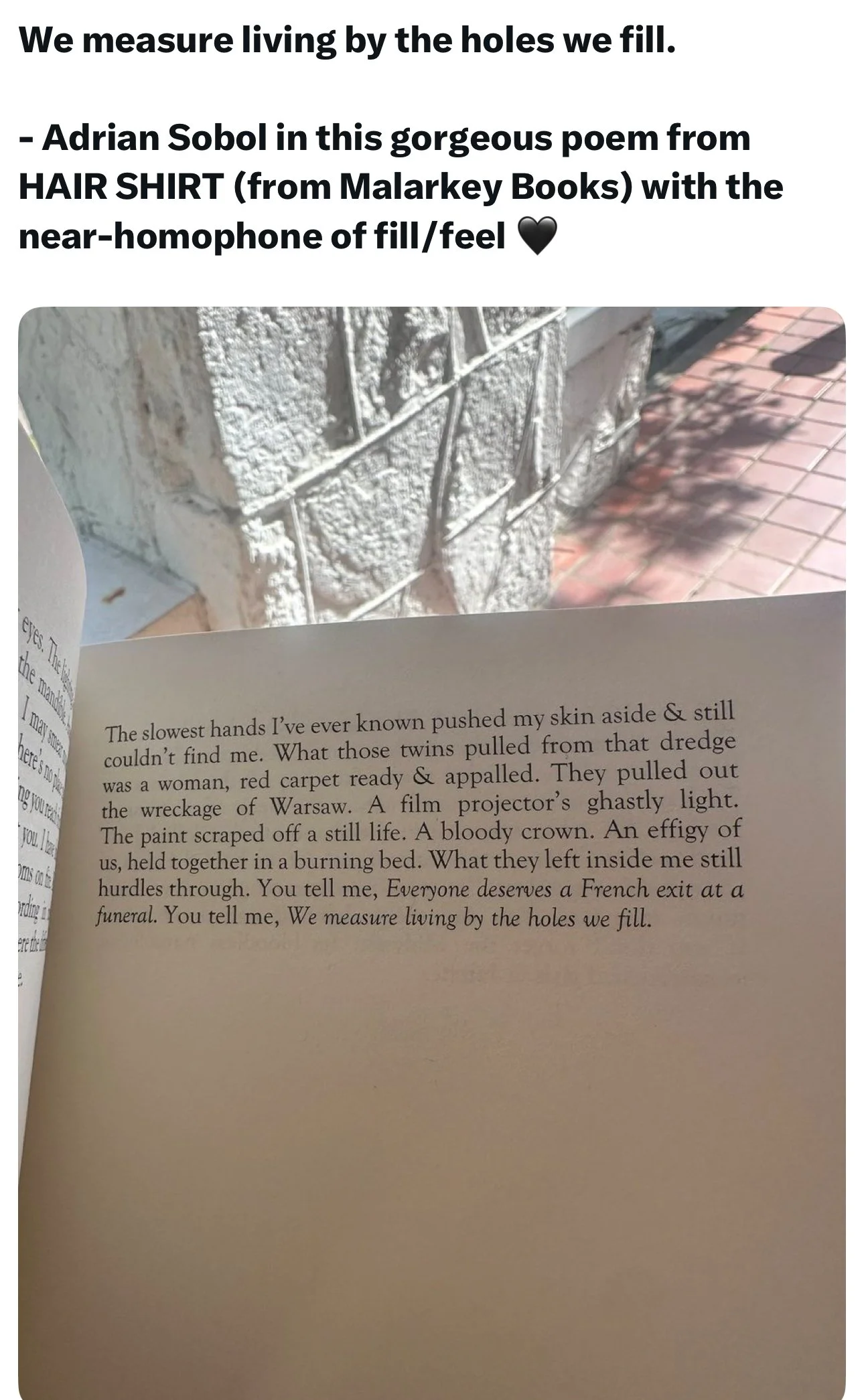

The refrain returns here, reminding us that she isn’t afraid when skating through the crowd at night because she is wearing her headphones, drowning out her surroundings with loud music, lost in the world of her head which happens to correspond with the radio song. “She gets rock 'n' roll and a rock 'n' roll station / And a rock 'n' roll dream.” She tunes in to the frequency of her own reveries, her own dreams. “She's making movies on location / She don't know what it means.” Each place she moves through becomes part of the movie generated by the music and motion. She doesn’t have to know what this ‘means’: her only commitment is to feel it, to move with it.

Narrativity enchants from the margins of movement. “And the music make her wanna be the story / And the story was whatever was the song, what it was.” The song is the story and she is part of it, part of this story told by the music and yet retold, re-made, by her relationship to it, just as a good book draws us into its spine, enabling us to recognize familiar traces and spaces that resonate and refract. Proust is summer’s king of that. Time is suspended: “Roller girl, don't worry / D.J. play the movies / All night long, all night long.” The girl isn’t choosing specific tunes or songs; she is just going along with the radio songs. She experiences agency or autonomy (she can go where she wants and listen to music and make a ‘movie’) with limitations (she can’t pick the song, she can only make a movie from the song that is given).

The next verse delights me because it crosses again into that ambivalence. “She tortures taxi drivers just for fun” — so she gets pleasure from provoking or upsetting taxi drivers; “She likes to read their lips” — so she engages them in some form of conversation that elicits a response; She “Says, ‘Toro, toro, taxi, see ya tomorrow, my son’” — so she calls to them with the classic call a toreador makes when trying to lure a bull closer and capture his interest for the purpose of wounding him — “I swear, she let a big truck graze her hip” — so she puts herself at risk, which is consistent with the toreador’s practice in bullfight, but also doesn’t seem to put the taxi drivers at risk. This “torture” isn’t physical but flirtatious. There is no risk to anyone apart from herself, the girl on the skates.

And this reminds me of Paul Valery’s essay on dance, where he studies the dancer as an exercise in philosophy. “For the dancer is in another world; no longer the world that draws color from our gaze, but one that she weaves with her steps and with her gestures,” writes Valery. “And in that world acts have no outward aim; there is no object to grasp, to attain, to repulse or run away from, no one which puts a precise end to an action and gives movements firm outward direction and coordination.”

Do the actions of the girl on skates have a purpose, apart from moving across the streets and through the city? Does she have an outward aim, apart from listening to music and living in that skateaway dreamworld?

There are similarities between the girl and Valery’s description of the dancer, even if those similarities are most striking in the quality of absorption both seem to involve. The dancer is “in another world,” a word “she weaves with her steps and with her gestures”; the skater . . .

“Aw, she got her own world in the city, yeah / You can't intrude on her, no, no, no, no / She got her own world in the city / The city's been so rude to her.”

Now the first refrain is repeated and followed immediately by the two verses of the song refrain, moving towards the song’s diminishment through repetition and repositioning, the result being a snowman-shaped refrain-combo:

No fears alone at night

Sailing through the crowd

In her ears those phones so tight

And the music's playing loud

She gets rock 'n' roll and a rock 'n' roll station

And a rock 'n' roll dream

She's making movies on location

She don't know what it means

But the music make her wanna be the story

And the story was whatever was the song, what it was

Roller girl, don't worry

D.J. play the movies

All night long, all night long

A slight shift: “No fear alone at night” becomes “No fears alone at night” in this repetition. The girl moves from the repudiating the condition of one fear (the fear of being alone at night in the city) to repudiating the condition of many fears (all the fears that emerge after being alone at night in the city long enough to see the city, to taste life, to witness the possibilities of hurt and harm).

Au fin: the repetition, humming. The phased out humming and sound-making — “Slippin' and a-slidin' / Yeah, life's a rollerball / Slippin' and a-slidin' / Skateaway, that's all” — sums up life in a “rollerball,” or a skating disco scene where couples move past each other on wheels, and coordinate their actions into steps and slow dances. But the girl of Skateaway never dances in the lyrics: she skates against the grain and plays with danger. She listens to her own music on headphones. There is no sense in which she is dancing to the same music as those around her. If this is a rollerball, then she imagines it and remains its single knowing attendee.

In the ending, Knopfler repeats the titular world, invoking the “Skateaway” space, while vocalizing the skater’s imaginary (as he perceives it) and quoting this imaginary in “Sha-la sha-lay, hey, hey / Skateaway Now, sha-la sha-lay, hey, hey / She's singing sha-la sha-lay, hey, hey…”

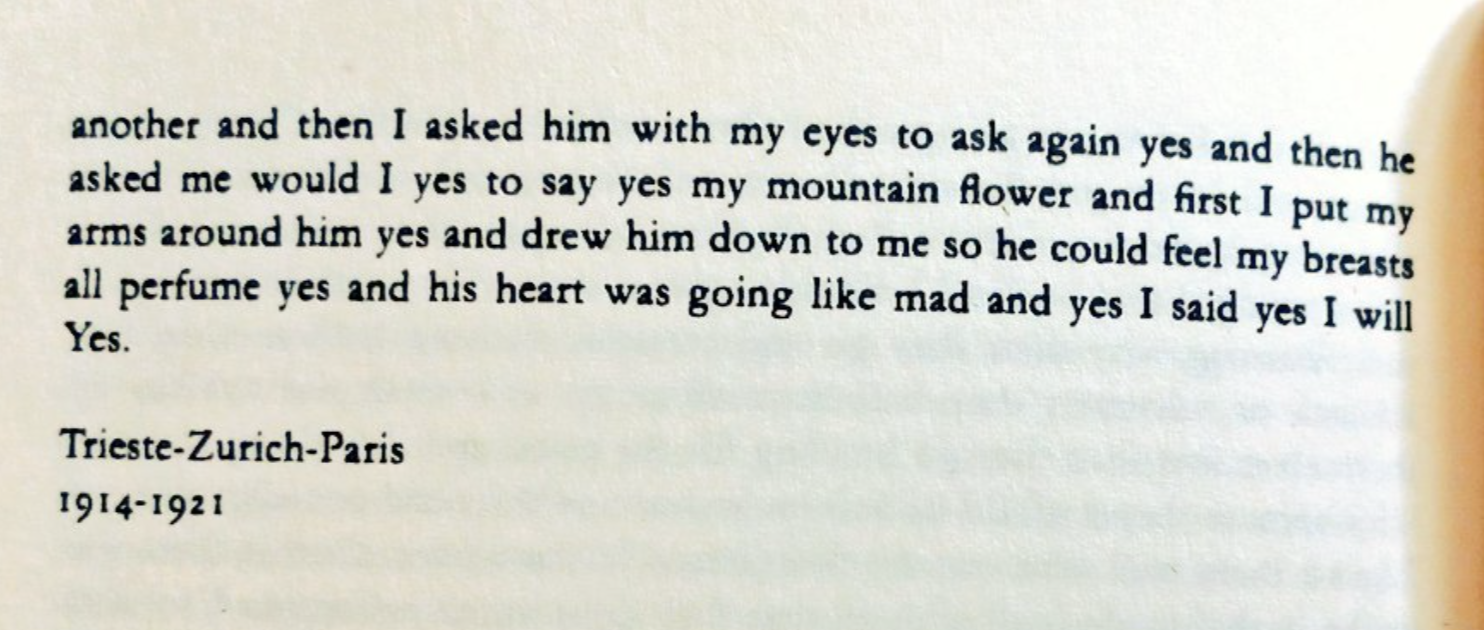

—- And there is seepage in the SHA-la, sha-LAY stresses of the skateaway, a soft interpenetration that reminds me of what Beatrice Douvre evoked in (a line from her poem, “She Who Goes Beyond”) “the fascinated distance that bleeds,” which is to say, music has always pulled me from myself: it is better at doing so than any human voice or conversation. Perhaps this is due to the nature of its invitation, for music unfurls the texture of dreams, drawing us towards the imaginary, insinuating through beats, tempo markings, instrumentation the possibility of motion into and away. The body climbs the steps while discovering them. The imaginary holds sway, unimpeded by hyper-consciousness. And yes, there is sublime pleasure in this.

Towards the end of his essay on dance, Valery shows his hand in a sprawling and marvelous sentence (italics mine):

I wanted to show you how this art, far from being a futile amusement, far from being a specialty confined to putting on a show now and then for the amusement of the eyes that contemplate it or the bodies that take part in it, is quite simply a poetry that encompasses the action of living creatures in its entirety: it isolates and develops, distinguishes and deploys the essential characteristics of this action, and makes the dancer's body into an object whose transformations and successive aspects, whose striving to attain the limits that each instant sets upon the powers of being, inevitably remind us of the task the poet imposes on his mind, the difficulties he sets before it, the metamorphoses he obtains from it, the flights he expects of it— flights which remove him, sometimes too far, from the ground, from reason, from the average notion of logic and common sense.

I don’t know when the girls will wander in tonight, or what the proper ceiling for their wanders should be. I hope they find their skateaway, ride their unknowns, tarry near their fascinations, carry only what frees them, make movies whose meaning eludes them.

The restless, tempestuous, eternally-hungry physical part of me can’t resist the invitation, the beat of it, the thrill of feeling the body lose and find, lose and find, SHA-la, sha-LAY . . . rollERgirl, don’t WERE-ry, dj play the MOVE-ies all NIGHT long . . .