I do not profess that writing may not and does not in fact play this role [man’s exploitation by man], but from that to attribute to writing the specificity of this role and to conclude that speech is exempt from it, is an abyss that one must not leap over ... lightly.

– Catherine Malabou

What was left on the cutting room floor?

— Gabriela Denise Frank, in a line left on the cutting room floor of an interview draft

FALLEN NESTS

While meandering up and down the street with Radu, pausing at his usual pee-mail stops, even venturing to add a new box to the map of his scent-relations, a Carolina wren chirped my name and the world shimmered, froze, melted, became momentarily Otherwise. On the day before leaving for Romania last month, on a similar walk with Radu, I

I thought about a nest I’d come across a few weeks ago, on a similar walk, the day before we left for Romania— and feeling the world’s axis tilt into the eerie. Had I taken a photo of that fallen nest? Flipping through the images on my phone . . . green, the walk, the tree, the nest, the small blue egg crushed within it. The egg’s shell struck me multiply, but also figuratively, as the broken skin of a curved origins. Not a surface so much as the absence of roundness, the not-whole of a thing that breaks when a life hatches from it or, breaks too early, falling into a story of accidents.

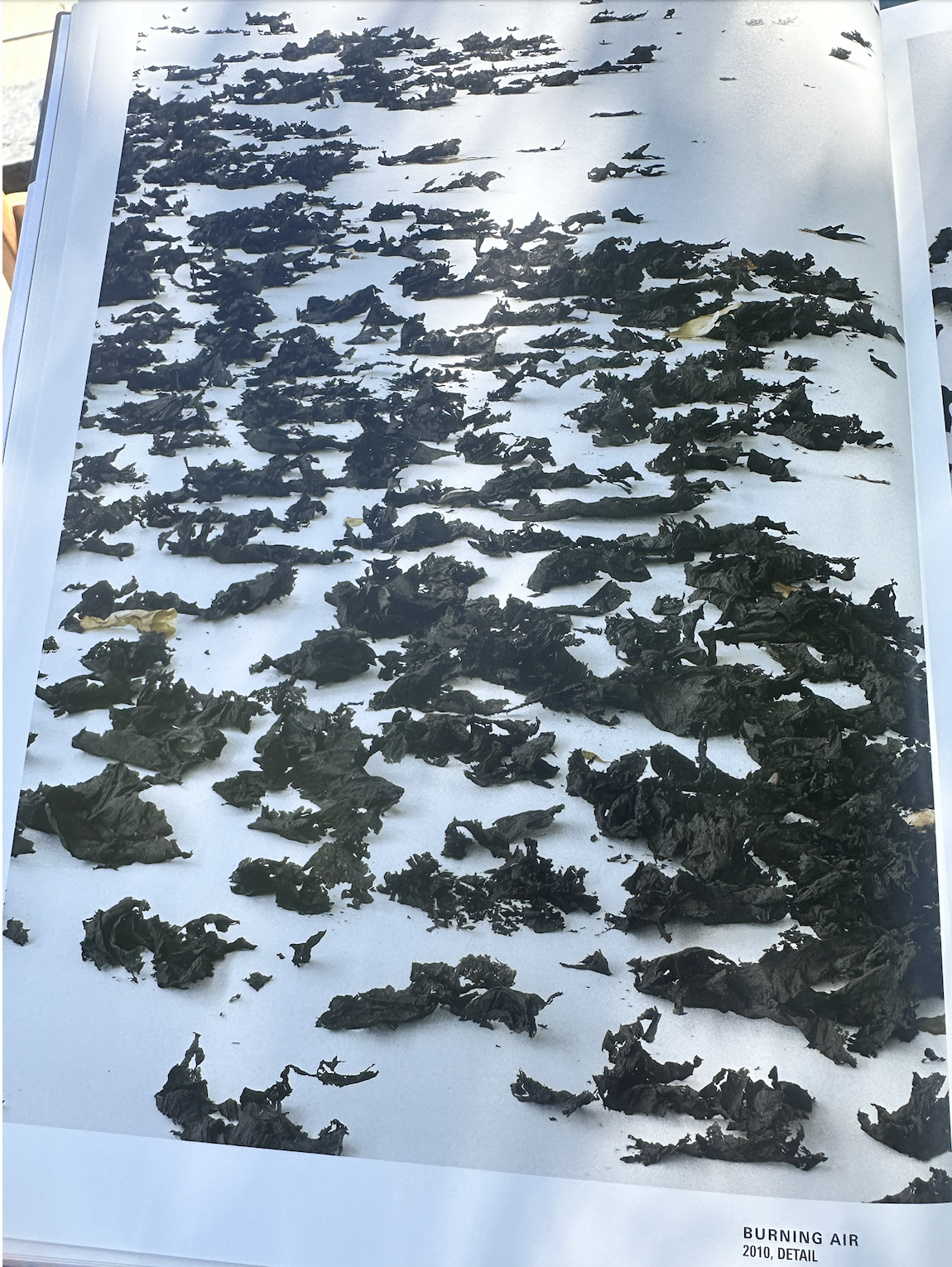

The persistence of this image inflamed my curiosity, much as the “abyss” did on in 2021, when pandemic consigned us to the house. In this case, what emerged wasn’t a word but the process of wording, itself, situated in an restless urge to animate the scraps and remnants —- to make an alternate nest from the shadows of things that got cut from my conversation with Gabriela Denise Frank (which will be published in The Rumpus next week). In that interview, when Gabriela queried my writing process, I spoke of juxtaposing fragments and pieces of sound, but there is, perhaps, another way of ‘saying’ the same thing, which is by enacting it.

From my fever for lost and fallen things: two fallen nests. Two structures arose the cuttings of wood chips at the base of the interview’s final draft. The first nest is self-conscious: the speakers are set apart by/in quotation marks. As these quoted words (the “cuttings”) have not or will not be published in an official journal, there is a thrill in according them the status of words that were scored and prepared for performance. The second nest is composed entirely from my own words, the ones looking up at me from the draft’s cutting floor, asking to be placed in an un-synced relation that is not quite a conversation.

Both nests have their own lullabies, though what lulling might sound like for occupants of fallen nests remains unclear. Nevertheless.

Fallen Nest 1: Cracker, “Big Dipper” (1996)

“FALLEN NEST 1”

Gabriela’s kindness and brilliance rises from the screen immediately. Moved by her demeanor, I visit her website and marvel at her art. Now, I want to tack the boat and focus the questions on the provocative asynchronies in her work rather than consider the meh of my own. But Gabriela asks. “How and where does this message find you? What is giving you pleasure these days?”

And I reply. “Dear Gabriela, this message finds me at home in Birmingham, at 12:14 a.m., feeling grateful to you, while also paring down a draft essay, which, in my case, involves cutting hundreds of words at an hour when letting go of words is less onerous. Pleasures: bright crimson azaleas, the overwrought aroma of wisteria, archives of e-flux index, making collages from stills in old family films, Charlotte Mandell’s translation of Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste, recent encounters with poets like K. Iver, the unsayables that drive the having-said, a year with no surgeries, the splendid critique of my teens, the birdsongs that spring lays near my window.”

Gabriela turns towards the furred one. “And (importantly!) how is the wonderful, terrible Radu?”

I reply. I am conscious of being the one who is replying. “Radu is as wonderful and terrible as the poems he courts on the front porch. He has turned his melancholic heart away from books and invested in birdwatching and barking at bumblebees. I could not be more proud—or more embarrassed. Love does this to us, I think. Love impels us to recognize how the beloved is seen by others, which is often much less appealing than we care to admit.”

Gabriela mentions the poem “Alternative Index Discovered in Franz Kafka’s Notebooks.” She wonders how I “came to the index as a scaffolding” for it. “How did the poem start, develop, and evolve with this form? What was left on the cutting room floor?”

I tell her a truth. “Those poems were lifted from the cutting room floor of my notebooks, where I indulged in cross-annotation of Kafka’s correspondence, published fiction, and diaries. An index is a lovely apparatus for shaping: it presumes to know without acknowledging its bias. I wanted to mess with that way of knowing implied by structure. In the sidereal, I hear Svetlana Boym whispering, yes, yes, ‘nostalgic manifestations are side effects of the teleology of progress.’ The structure creates the conditions under which the sidereal develops. The poem listens and attempts to depict this.”

At this point, Gabriela’s insight gives me goosebumps. She says, “My Heresies ends with alliterative epiphanies in “Epiphania”—a closure that opens. (It makes me think of Hélène Cixous: “A feminine textual body is recognized by the fact that it is always endless, without ending. There’s no closure, it doesn’t stop.”) Why and/or how did brightness become an end for this poem and this book? How does brightness here (different from redemption) maintain the distance between the room of the poem and the world it imagines?”

[Since Gabriela links the essay on closure in her email, I have elected to leave that link and set it apart with an italicized quote-link of her works, to be distinguished from various and sundry links peppered by yours truly/untruly throughout these nests.]

I fumble with hauntology. I struggle to articulate an apposition that continues to trouble and excite me. I reply. “Since you mention Cixous, I confess that I found myself thinking of her interviews and conversations when reading your questions. There is a similar discursivity alongside an extraordinary close attention that you bring to the art of the ask. Disclosure interests me more than closure; dialectic, for me, doesn’t aim to conclude. The poem risks inclusiveness by expanding the scope of knowledge, and, in so doing, asks how we know what we claim to know. Or believe.”

Photo album of shavings, coincidentals, and the zombie of a manuscript related to the conversation about my heresies

Fallen Nest 2: The Afghan Whigs, “I Am Fire” (2014)

“FALLEN NEST 2”

But the first passport — “Untitled” (Passport), 1991 — the original passport in Gonzalez-Torres’ series . . .

. . . is one of my personal favorites, my backup, my gauntlet . . .

. . . This “(passport)” contains a homeland in my head, the papers for a country worth claiming, a space to which I would willingly belong, which drove the prefatory poem, “Byline, Be Sky,” and its longing for a byline that moves like wind rather than grounding itself in status. One part of the writer is always . . .

— writing.

. . . Memorials conspire with eternity to make something permanent. Where do we go after we die? Gonzales-Torres’ long-term lover, Ross Laycock, died of AIDS in 1991. When do we stop moving through one another? What does eternity look like? A stack of blank white paper could be anything, anyone, anyplace, anytime. A poet in Alabama meets the spirit of Cuban-American queer conceptual artist in that indeterminacy.

When writing to a friend the other day, I found myself trying to describe why . . .

Certainly . . .

Speaking of materiality . . .

. . . Hannah Zeavin’s Mother Media offers a brilliant look at the evolving technology in mediated forms of modern parenting.

Performing ‘civilization’ seemed silly in context. I mean . . .

Your questions delight me.

I treated billboards as profit-seeking entities who want something more than money from me. “What are you missing?” I asked that woman with very white teeth on the billboard near my house. “And what do you need me to normalize in order for you to feel big enough, or strong enough, or great enough?”

While living in Paris and trying to write what would become The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Briggs, Rilke sat in on courses by sociologist Georges Simmel (as did Robert Musil and Walter Benjamin). Simmel’s influence on Rilke was tremendous; he wrangles with his theories on love and affinity throughout Malte. We don’t study Simmel enough. His writing is still difficult to find in translation. In thinking through socialization and modernity, Simmel noted that our utilitarian, role-based conceptions assume that love can and should lead to “happiness.”

. . . Like Johannes Kepler’s mother who took him to the peak of a hill as a young boy so he could watch the great Comet of 1577 shoot across the sky, my mother exposed me to things I could not forget — everything from catacombs to honeysuckle-naps. Unlike Kepler's mother, my mom was never accused of witchcraft by a well-connected girl named Ursula who invented a witch in order to disguise her own abortion from the religious leaders. Catherine Kepler spent the winter of her seventy-fifth year in a German prison. She died shortly after her release on April 13, 1622. I was born on April 13th, the day Kepler's mother died. As a writer, coincidence is material.

On our walk home last night, the man told me to stand in the green gap. And so I did.

“The masses are rushing, running, charging through the age. They think they are advancing, but they are simply running on the spot and falling into the void, that is all.”

— Franz Kafka, prefiguring the 21st century

*

Adrian Sobol, Hair Shirt (Malarkey Books, 2025)

Alina Stefanescu, “ABYSS: pandemic diary, 2021” (in pdf, since the original website is gone)

Brad, “Buttercup” (1993)

Cracker, “Big Dipper” (1996)

Gabriela Denise Frank.

Hannah Zeavin, Mother Media: Hot and Cool Parenting in the Twentieth Century (MIT Press, 2025)

K. Iver.

Paul Valéry, Monsieur Teste translated by Charlotte Mandell (NYRB, 2024)

The Afghan Whigs, “I Am Fire” (2014)

The Flaming Lips, “Always There, In Our Hearts” (2013)