Philosophy and literature are speculative constructs of the commerce between word and world. Our first ontology, that of Parmenides, is a poem.

— George Steiner

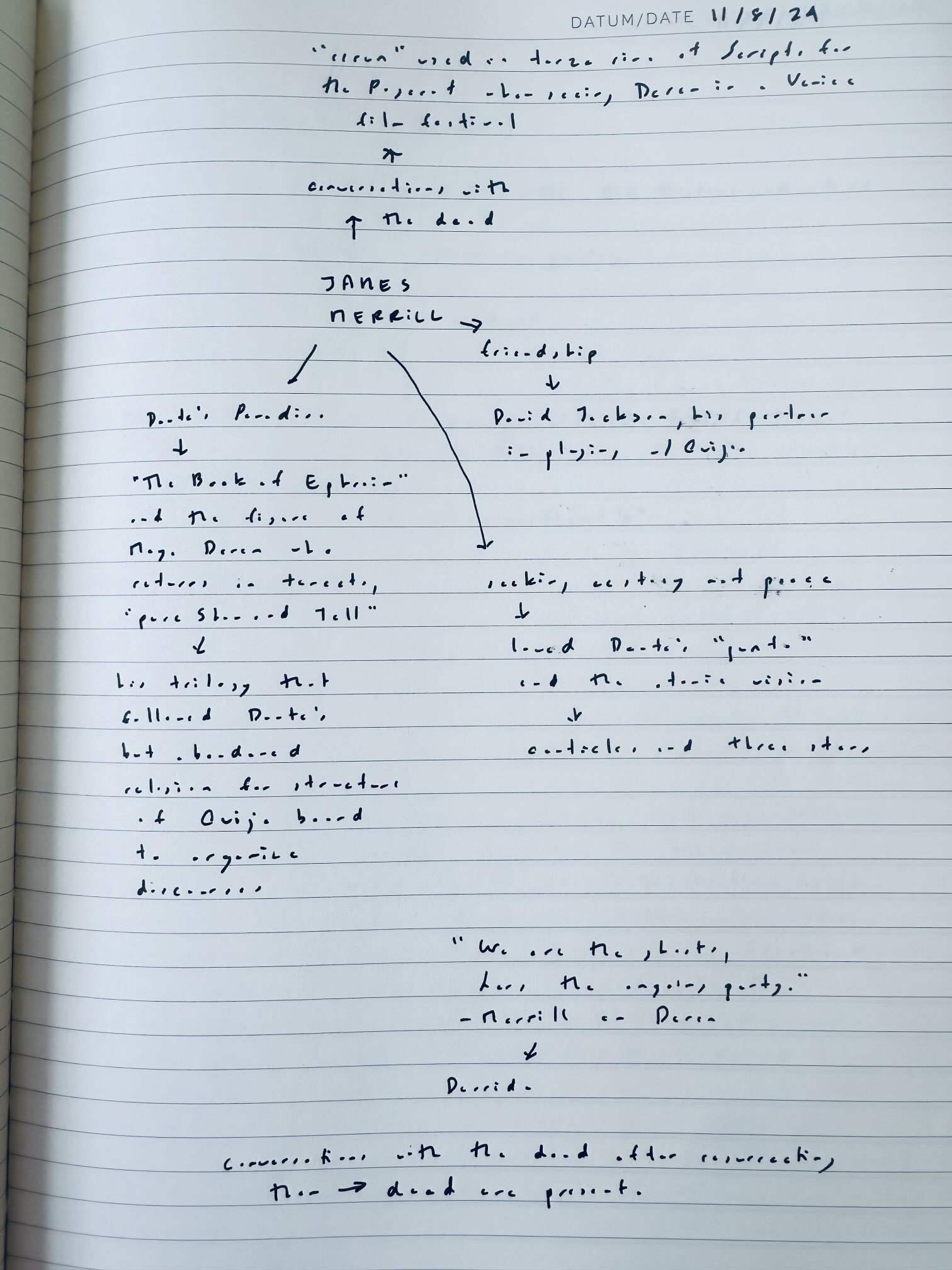

Chasing “rerun” through Maya Deren late last year.

1

Constitutionally, my notebooks resemble my dog, Radu, in that they alternate between butterfly-chases, speculative ornithologies, lyrical feasts, and nervous deconstructions. Returning to that hand-scribbled madness delights me the way a busy dungeon delights the alchemist. Months passed since I last lit a candle to wander through the notebooks’ tunnels, or deliver them into the Arial 10 pt text of official existence.

Determined to end the drought, I dove into one of the blues this morning, and dawdled for an hour or so, letting myself “chase the feeling”, to quote Kris Kristofferson against the grain of the alcohol central to his own “chase”, which is to say, being drunk, thereby interposing my own particular addiction, namely, the thrill of studying language and texts, within the stresses and beats of his. A structure of feeling chasing the feeling while Radu watches worriedly from the grey couch.

Jack you were wrong (or not

the radio is not from Mars

it is sitting here it has

the world

by its short

wavy hairs, home.

— Pierre Joris addressing Jack Spicer in “Short Wave Radio #2”

2

The notebook is my short-wave, my world of “wavy hairs, home,” the landing space for sound waves that stick in my head. In them, as elsewhere, I often query what brings us to the page, and whether (or which) particular experiences of incompletion put a creative pressure on language by making words want something from the world.

“If the insights of the past few decades could newly mobilize shame, shattering, or melancholy as interesting, as opposed to merely seeming instances of fear and trembling; what if we could learn from those insights and critical practices, and imagine happiness as theoretically mobilizable, and conceptually difficult?” asks Michael Snediker in “Queer Optimism” (italics mine). And: “what if happiness weren't merely, self-reflexively happy, but interesting?"

I’m interested in the desire of sentences as well as the forms that seek to disavow desire in the name of rigor or righteousness. “I always hung around in the street after school because of love,” said Chantal Akerman:

Love makes you hang around. I used to walk a girl a couple of years above me to the Gare du Luxembourg. We would talk for a long time, she would miss one train, sometimes two, to talk to me for longer, even when it was raining. I can’t remember what we talked about. Whenever it rained her long blonde hair became darker but it didn’t matter. She always ended up getting on a train and I would always return home. I didn’t know what love was at the time. But that was surely it.

Nothing ever happened between us but it was love and it was what made school bearable.

I would wake up at the crack of dawn every day to get to school early to meet her. We would rush to meet in-between our classrooms to talk just for five minutes. We had so much to say to each other. So it was worth it, even for five minutes. But it was never enough.

Akerman specifies a duration— “five minutes” —- here. She locates the bearable in this brief temporal dimension characterized by limitation. A short snatch of time. A thing that was never enough. A blip in which her relationship to infinitude was being negotiated by waking up early, rushing, meeting, and being left with the “so much” decades after the older girl had vanished from her daily life.

3

I believe that, in every person, there is an area which speaks and hears in the poetic idiom . . . something in every person which can still sing in the desert when the throat is almost too dry for speaking.

— Maya Deren, “A Statement of Principles”

In a 1967 interview, while answering a question about his methodology, Michel Foucault recounted a childhood nightmare:

A nightmare has haunted me since my childhood: I am looking at a text that I can't read, or only a tiny part of it is decipherable. I pretend to read it, aware that I'm inventing; then suddenly the text is completely scrambled, I can no longer read anything or even invent it, my throat tightens up and I wake up. I'm not blind to the personal investment there may be in this obsession with language that exists everywhere and escapes us in its very survival. It survives by turning its looks away from us, its face inclined toward a darkness we know nothing about.

The darkness we can only imagine: the throat too dry for speaking, the throat tightening, the mind settling on that part of outer space believed to be empty, silent, and dark which scientists call ‘vacuum’. Researchers have listened to vacuum by using sensitive, light-detecting machinery, and what they found was omnipresent sound, an ongoing random noise that permeated the dark ‘silence’ due to the presence of subatomic particles that appeared and disappeared spontaneously.

Nothing is entirely empty, or not in the way we imagine emptiness to be. “Philosophy and literature are speculative constructs of the commerce between word and world” and in that world of words, “our first ontology . . . is a poem,” said George Steiner. To borrow a syntax of feeling from Frank O’Hara, I am always eating a piece of my hair in the photo that has given me up.

4

Silence appears in the presence of the divine, as George Steiner noted, but 20th century silence, for him, includes the place where “language simply ceases.” The poet sinks into this thing with the abyss at its hem.

“Clairaudience” is the hearing of what is inaudible. Just as clairvoyance is the seeing of what is invisible. Both clairaudience (a.k.a. remote hearing) and clairvoyance press up against the limitations of space-time. “A stress is born in time, and in sound, meaning and emotion; but it also stands outside time in a sort of minor, eternal present, a trembling instant which half stands still, partly resisting the flow of the line which creates it,” writes Daniel Muzyczuk. The stress’ “great fascination” lies in the possibility of representing “a little model of how our minds relate the instant of time to the flow of time.”

"Silence has invaded everything, and there is still music," John Cage wrote in For the Birds.

“A poem is about knowing something both all at once and in its unrolling in time,” wrote Alice Notley, whereas “a song is more about being in time.”

“Could it be that in songs, the unfolding of time prevails over the eternal precisely because songs situate the stress?” wonders Muzyczuk.

There are variations within silence, as, for example, when silence differs from itself when by gaining layers, bringing various silences into relation with one another.

Seven minutes of yellow . . .

And such do love the marvellous too well

Not to believe it. We will wind up her fancy

With a strange music, that she knows not of . . .

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Remorse

Jack you were not wrong

But it was never enough . . .

*

Adam Thirlwell, “Diary of Nuance,” The Paris Review (Jan. 24, 2023)

Benjamin Biolay with Vanessa Paradis, “Profite” (2012)

Daniel Muzyczuk, “Ten Lessons in Clairaudience,” e-flux journal (April 2024)

George Steiner, “A Reading Against Shakespeare,” the W.P. Ker lecture for 1986

Maya Deren, “A Statement of Principles,” Film Culture 22/23 (1961)

Michael Snediker, “Queer Optimism,” Postmodern Culture 16.3 (2006)

Pierre Joris, “Short Wave Radio #2”

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Remorse (1813)