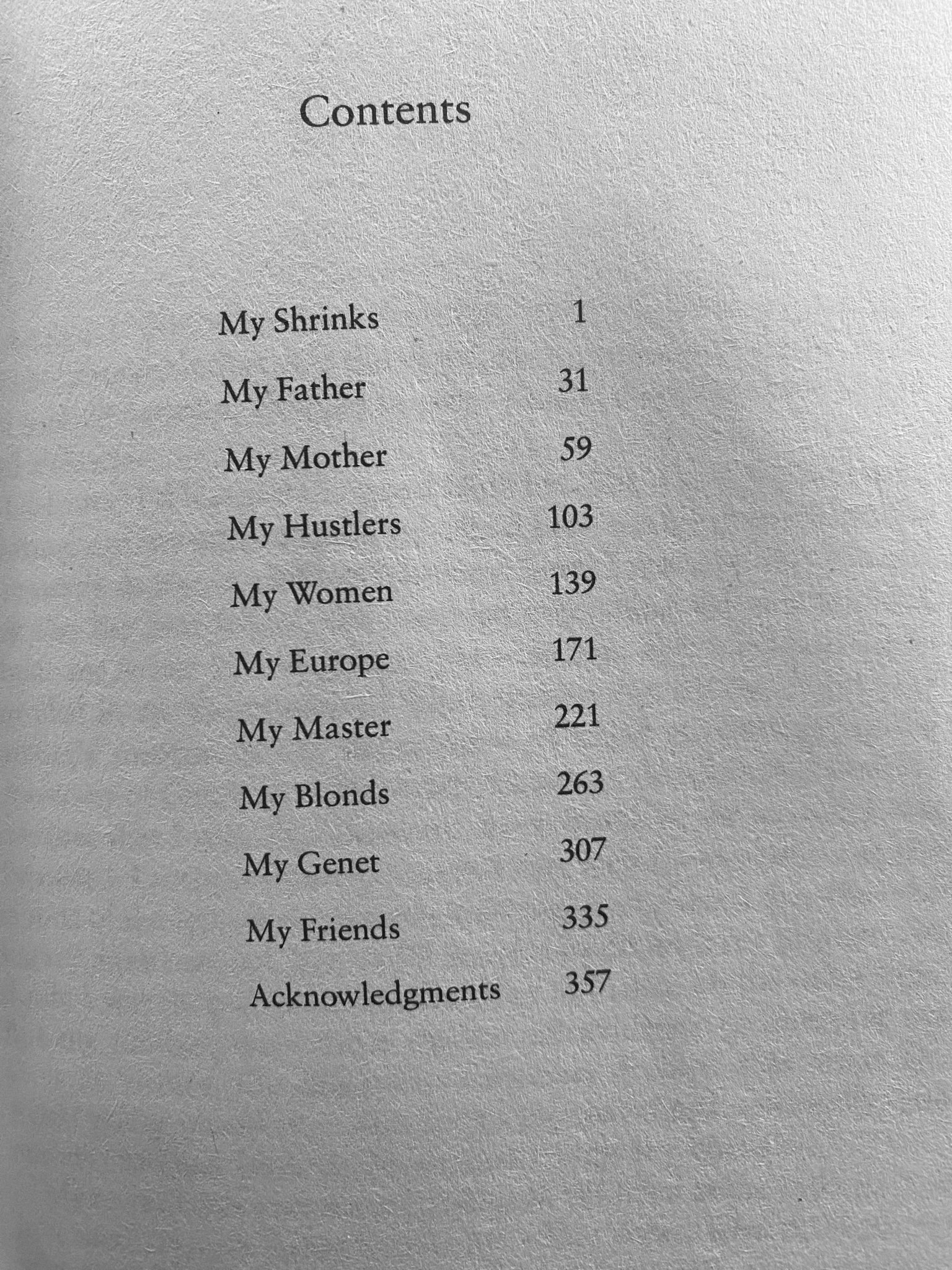

The Dark Brain of Piranesi and Other Essays by Marguerite Yourcenar (FSG)

Reverse Engineer by Kate Colby (Ornithopeter Press)

The North China Lover by Marguerite Duras, translated by Leigh Hafrey (The New Press)

Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux, translated by Tanya Leslie (Seven Stories Press)

“The Meridian” by Paul Celan, translated by Rosmarie Waldrop (Routledge)

*

My asterisks are many, but the first was given to me in the benumbed penumbra of a middle-school memory in classroom where a large starred and barred flag hung near above the silver pencil sharpener that occupied the wall opposite from the sky that owned itself and everything else outside the long horizon of windows.

The birds were lucky to be winging it, I thought. For I, too, wished to wing my way elsewhere.

In the grips of that cliched wing-longing, as a girl who had yet to dissect a quail egg, potentiality stretched out before me like the lie of an American vacation. Everything was just waiting to happen. Like a solid, adolescent stereotype, I was waiting to happen and to be happening and to be happened-to.

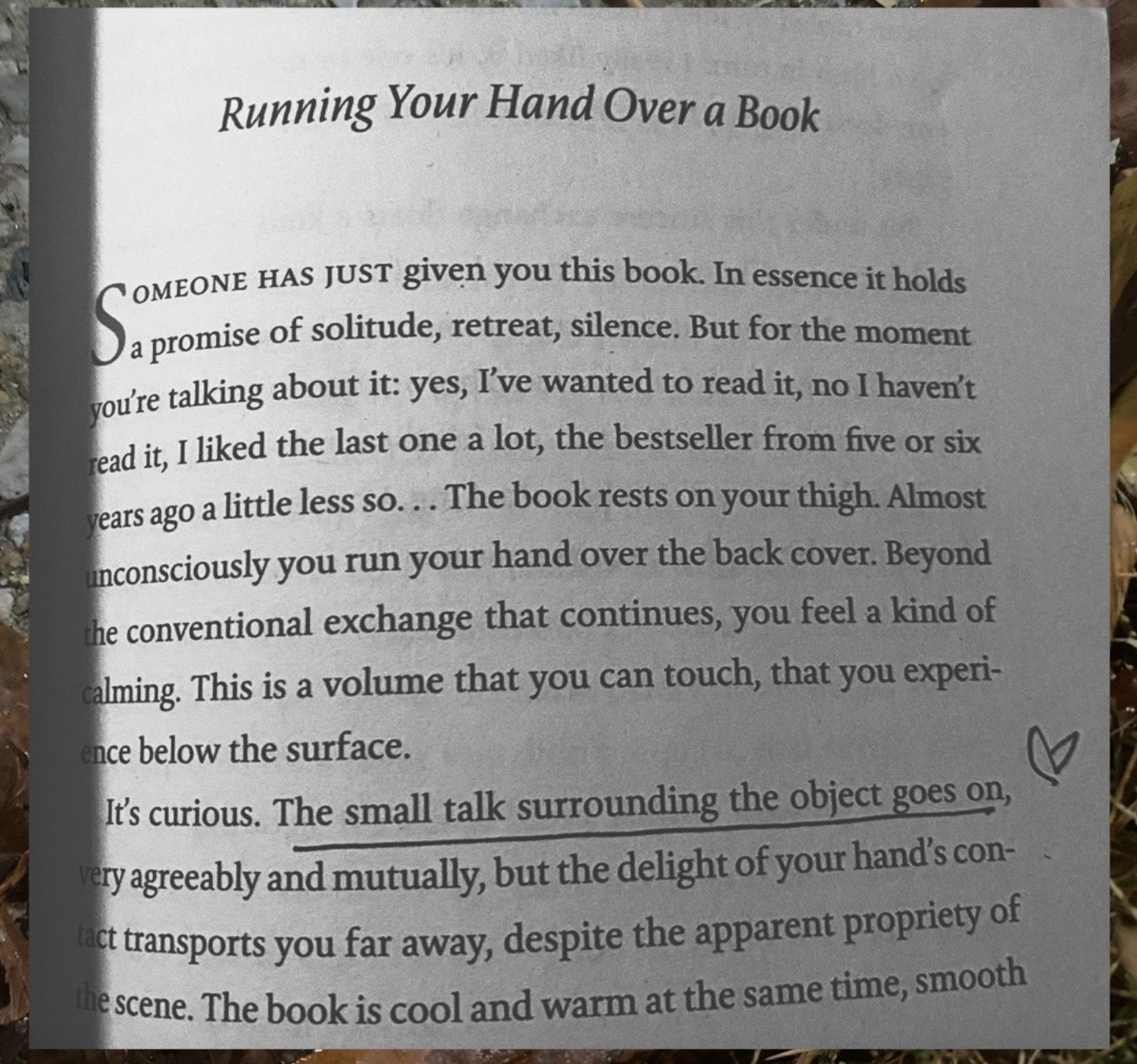

While waiting, I prepared myself by writing and reading about how it happened. I was an insufferable little zealot of bibliomania who wrote as she read and implicated her adolescent, very-human self in various dialogues with her condescending, age-flouncing reader-self. Book-zeal shelved itself alongside my loathing for ‘school’, where everything moved at a snail’s pace without venturing into the thickness of the thing being studied. We learned how to ogle the surface of steaks but not how to cut the meat and peer inside it. We were too young for both knives and analysis.

Still— there were marvels. Among them, the day when the word asterisk first tumbled from my teacher's mouth.

I remembering hearing a shot star, a comet with spikes, a nebula who had sinned against the cosmos and been expelled to extragalactic activities. Surely, the asterisk was exiled cosmic material; it even had "a risk" buried inside it.

I held my breath as the teacher drew an asterisk on the chalkboard.

The star appeared.

The voice explained that one could attach stars to sentences.

School bears little relation to what some have called "reality," that temporal realism wherein asterisks are formally taken for markings that indicate the word buried within the word, or the thing at the bottom of the hole which becomes a word's variant. I scooped up that asterisk and took it home for future examination.

A few years later, I realized that the asterisk has a sense of direction: textual asterisks usually allude to something located at the bottom of the page.

"Look down," the asterisk whispers, "for additional material which qualifies or makes sense of the starred item."

The star must fall to the ground to be studied.

Perhaps this two-faced duplicity—being simultaneously cosmic and fallen—accounts for Dan Beachy-Quick's description of the asterisk as a creature both obvious and unavailable.

And if my asterisks are many, there is nothing to prevent me from sharing a few of them.

1. The asiding asterisk

A twinkling star is a tiny patch in dialogue with extraordinary darkness. Nothing twinkles without gesturing towards the way light winks, the way, winking, itself, is central to light's friskiness.

On clear nights, other stars congregate nearby. In their company, one imagines writing the night, using the eye as a fountain pen that dips inside the inscrutable texture of inky darkness. Poets are the fools who keep trying to write it.

A friend who studied astronomy lays countless gorgeous words in my lap and I admire their multisyllabic heft.

I ask questions about the end of a star and the beginning of a comet.

When leaving its orbit to meet us, a star loses its connection to the luminous.

Or maybe I am thinking of meteorites—and how an asterisk is a star until a human says a star has fallen, at which point it becomes a fragment of an imagined star, or a chunk of rock broken on impact?

The fragment of an asterisk cannot be a light. The fragment must be closer to a chunk of a meteorite, a scrap of the formerly-lit which encourages us to imagine the star.

I coax myself forward by implying that the poem’s challenge involves amplifying the nature of unavailability while incarnating it on the page.

I return to this (feeble) idealized tension to rationalize lifting a meteorite from an asterisk in Marguerite Yourcenar’s book, The Dark Brain of Piranesi and Other Essays, on a night when I cannot sleep.

To say a meteorite is a fragment of something larger that crosses paths with a dream in my notebook is simply to indicate that what I borrowed and buried in italics is not “a light”—-cannot be a light—and thus sever any connections to illumination. But here is how a first line might grow from an asterisk: “Erotic concerns aside, I dreamt I died, he said this morning.”

“The asterisk may open a poem by parsing the space between the notebook and the dream,” I wrote in my notebook, like the goofball one must be upon returning to the self that failed to finish imagining the thing that she believed needed saying.

A later date. “A poem's terrain is a landscape fashioned from absence and fragments,” I babbled to a different friend, on one of those morning when thinking aloud feels like walking barefoot between sea urchins, eking my way towards language before getting distracted by the superblue hue of this friend’s eyes, the countless asterisks and stars moving across the surface of that superblueness.

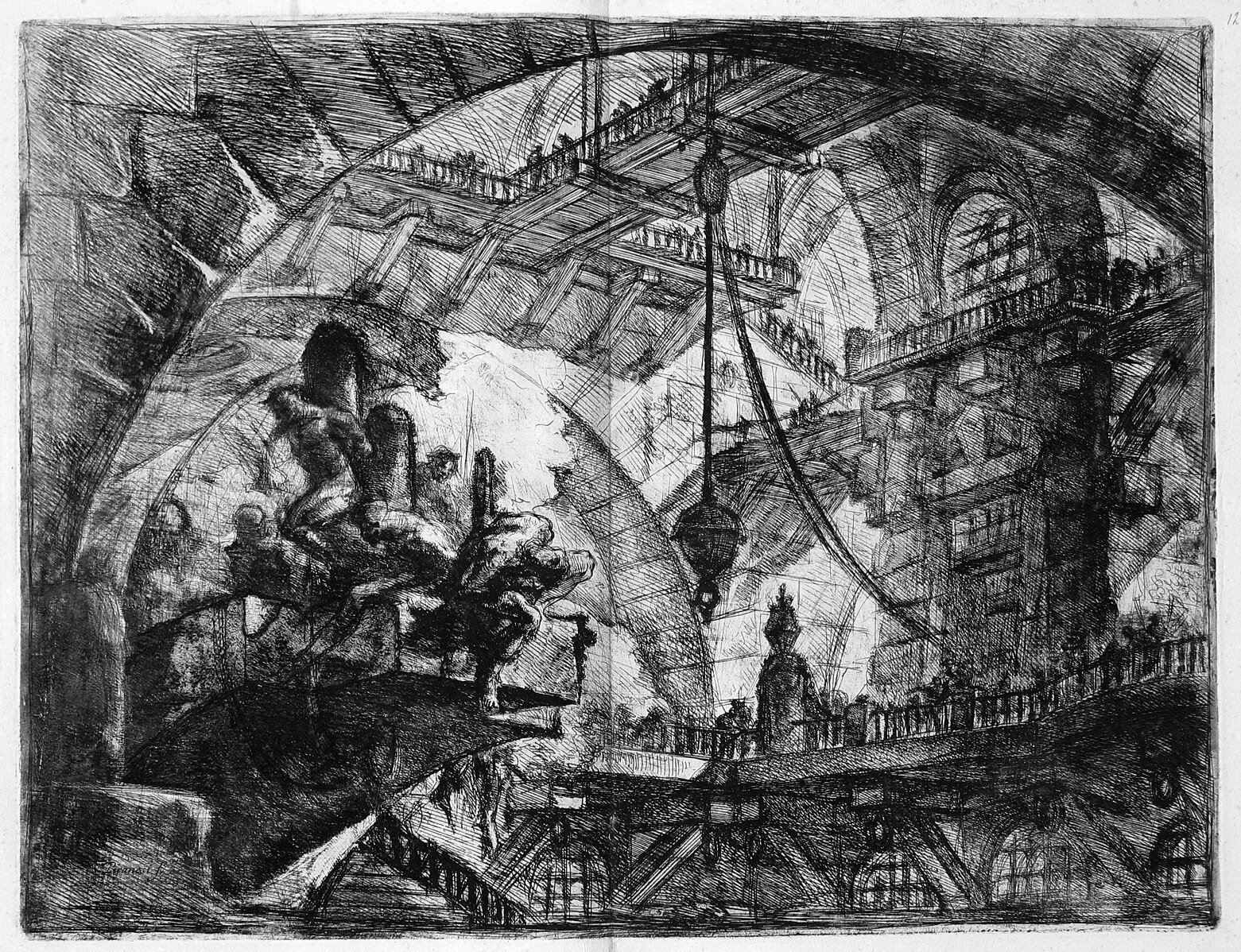

Giovanni Battista Piranesi - Le Carceri d'Invenzione - First Edition - 1750 - 10 - Prisoners on a Projecting Platform

2. The passive-aggressive asterisk

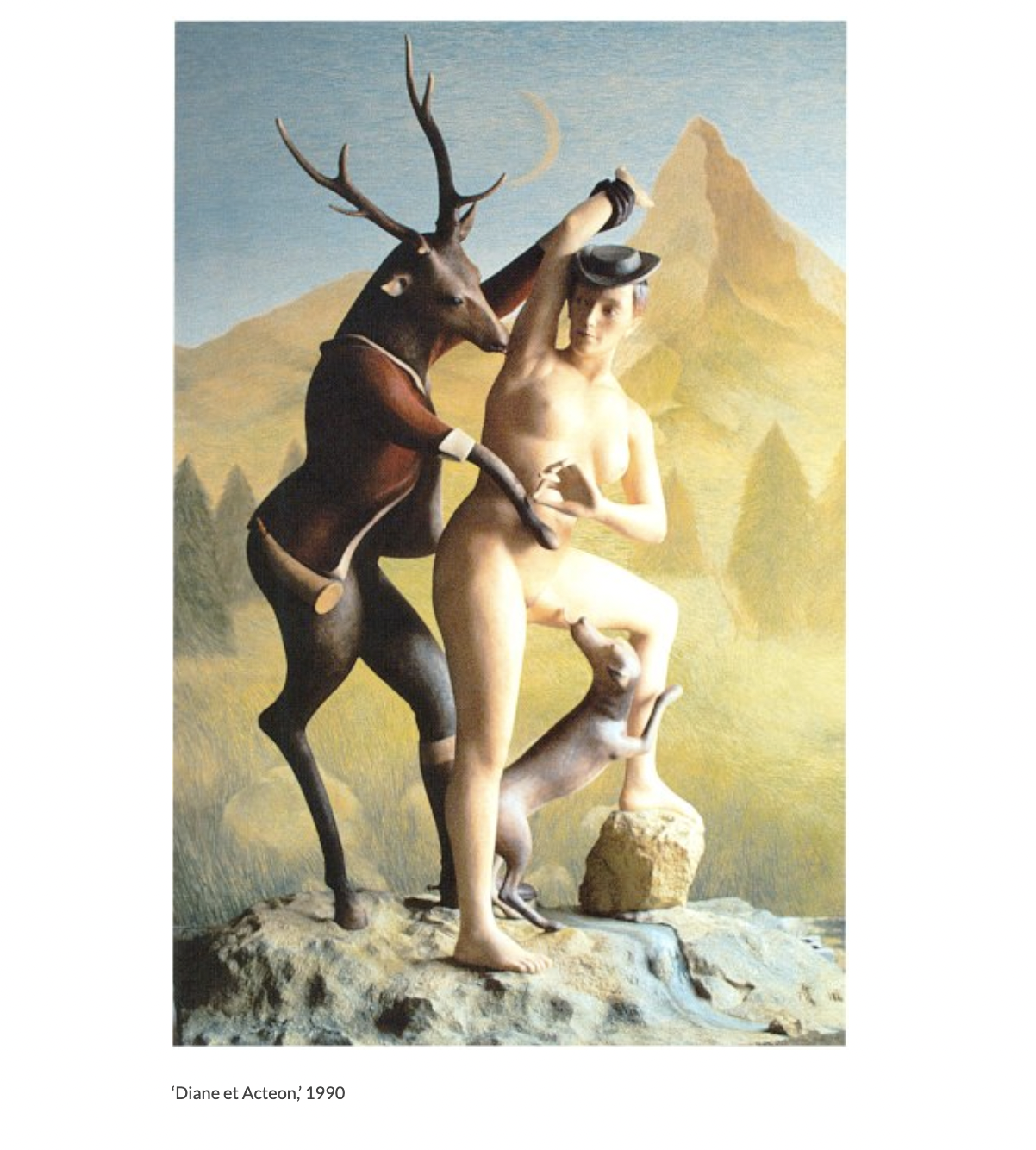

Piranesi’s Carceri (usually translated as “Prisons of Invention”) are architectural fantasies from the capriccio genre, but caprice feels tonally absent from them. Scale is stressed in the contrast between the small figures and the cavernous, sky-scraping spaces. Light is present and yet impossible to locate; it reaches in from a high diagonal without pronouncing anything. It is a light that won’t say what needs seeing.

In Yourcenar’s descriptions of Piranesi's carceral drawings, I’m drawn to a particular asterisk that she appends after a sensuous description. The feeling, again, is of that thick, material texture and then star pointing to its own reflection on the ground.

The fallen star reads as follows:

“Wondering if the modern reader's irritation in the presence of such effusion does not constitute a form of prudery as dangerous as any other. It is a perverse constraint upon passion, our recognition of its right to violence and not to a languishing or tender reverie.”

Y’s asterisk makes a quick critical point— a statement that doesn't want to be developed into an argument—defending the writer’s prerogative to luxuriate in an effusion of language. Accusing the anti-languishers of placing a perverse constraint upon passion, the tone is passive-aggressive. Lying in wait at the page's bottom like Gaston Bachelard's "imaginary paradox of a vigorous mollusk," this asterisk stores up that "most decisive type of aggressiveness, which is postponed aggressiveness, aggressiveness that bides its time." Perhaps the harmlessness of the asterisk is its disguise, and we assume its superfluousness; we confuse its stasis with an absence of sting. Yourcenar's asterisk is a vigorous mollusk. But "wolves in shells are crueler than stray ones," Bachelard warned.

3. The withholding asterisk

Not all asterisks are aggressive.

There is a cooler, withholding asterisk that conspires with the erotic by marking the words that must be whispered rather than declared. The asterisk-reader is one who craves the furtive sensation— desiring to know what was nearly said or almost uttered— of approaching the text's held-breaths.

"Like the shy one at some orgy" in Leonard Cohen's "Last Year's Man," the asterisk stands to the side of the action. The singer joins it in order "to see the serpent eat its tail."

One can hardly glimpse the whole serpent while socializing and doing Jaeger shots inside it.

Nor can one behold the serpent when riding it.

Cohen hints that those who want to know the serpent's secret must lean back against the wall and watch quietly.

4. The self-denying asterisk

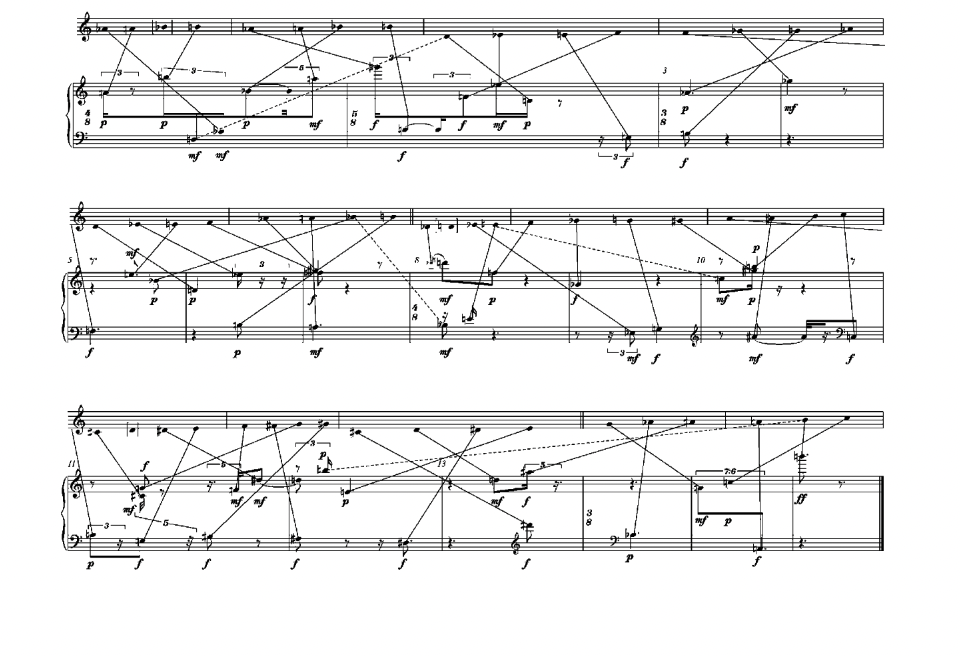

The asterisk's expansion of time is ripe for the poet's subversion.

And Kate Colby approaches the definition by undoing it. Specifically, in a poem titled “Integer”, Colby leaves an asterisk to rest inside the poem's third section:

* A thing complete in itself.

All that I can see from

the distance of the sun

the moon has broken

up with its light.

As a thing complete in itself, Colby's asterisk totally opts out of designating a note at the bottom of the page.

The poem's asterisk cracks its knuckles to indicate that it will not be serving its usual referential role. Here, the asterisk signals something, but gives us nothing. I love Colby's asterisk for how it stood me up in that emptied moonlight.

5. The translator’s asterisk/s

Usually, the translator's asterisk specifies (or provides) cultural context that may be necessary to understanding.

But it also reminds us that understanding requires additional information; the poem is not complete as is. While translating Radu Vancu's Psalmi from Romanian to American, my draft-asterisks profess their uncertainty, leaving their “and—and-but's”! like cigarette butts on the floor.

In translation, the asterisk steps in as notes on references, sources, quotations, and connotative meaning. Translation partakes of the dynamic wherein the text gets more or less infected by the translator's voice, depending on choices or decisions. But there is no other way to invite you into the meridian—one must risk being wrong or meaningless.

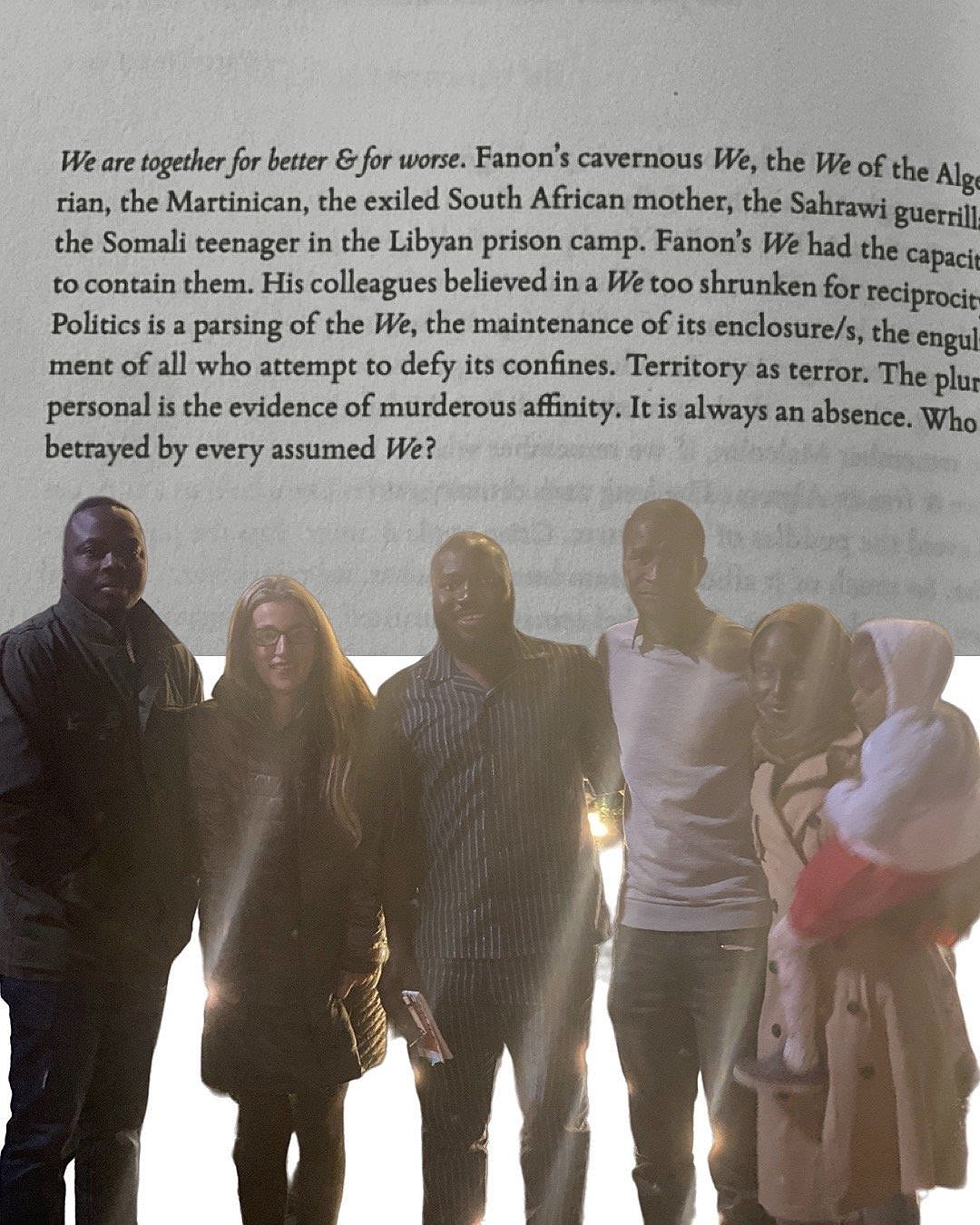

Vancu's epistolary poems enact a dynamic of futility and desire in relation to a shifting interlocutor. A letter creates the expectation of an answer; it craves a desire for a response. Like a stylite perched atop a pillar between earth and sky, Vancu's epistolaries speak from an exposed time and place towards the eternal. He beckons from places characterized by time (by seasons, by life) towards this You, this divine and intimate otherness—and this invocation alters time. The poem opens into the elusive temporality of the Otherwise, or what could be different, this thing Paul Celan called the "utopian light" in his oft-quoted Meridian speech:

But in the light of what is still to be searched for: in a utopian light.

And the human being? The physical creature?

In this light.

The encounter created by the poem projects itself onto a self, Celan suggests. "And once, by dint of attention to things and beings, we come close to a face, open space, and finally, close to utopia." Using snow to communicate the paradox of innocence and divine cruelty, Vancu describes the light in his son's eyes sparkling with snow. This white substance is the material Celan evokes in the poem describing his mother's death march and disappearance.

My translation notes stumble, pause, and mark the trail of my unknowings with asterisks. Am I allowed to make a connection or to assume a reference? Among my asterisks in translation notes for Radu, one refers to an early draft of Celan's Meridian speech, a draft in which he wrote the following after an asterisk:

Every strange time is other than ours; we are far outside, but in any case only at the edge of our own time; the perceived things are also there with us: they stand there where we stand at last: the things in the poem somehow partake of such “last” things could be, one never knows, the “last” things.

Since this section doesn't appear in later drafts, the asterisk feels indicative of an apocryphal Celan—if drafts can be considered apocryphal texts.*

6. The not-a-footnote asterisk

The asterisk sets apart, or captions a particular aspect of text. Unlike the footnote, however, the asterisk appends time while eschewing scholarly affect. It asserts itself as an oddity, as a locus of weirdness— even when it politely explains the Latin meaning of a phrase. Roland Barthes' asterisks, for example, disclose alternatives readings, etymologies, and phenomenologies.

Asterisks may function as asides, or statements gesturing towards something external to the text that applies an interesting, unexpected pressure through juxtaposition. I mentioned how Yourcenar’s asterisks are aside-like, particularly when contrasted with Duras’ directive asides that issue commands and tell the reader how to stage the imagined scene.

But I'm thinking also considering the way a casual, aside-leaning asterisk marks the space where writers dialogue with unofficial ghosts and sources.

Where the footnote fusses fastidiously, the aside merely suggests there is something intriguing in the eye which finds its precise hue replicated in the blues of a Bonnard painting. Do the blues recognize each other? The aside beckons the reader into an impression unattenuated by intellectual duty. The aside and text coexist in unspecified juxtaposition. The reader's imagination does the work of creating consequence.

In my notebooks, beneath the description of various karaoke solos and duets performed by our polylingual wedding guests, I find an excerpt from an essay published in 1990 by Polish writer Stanislaw Baranczak. Titled “Goodbye, Samizdat", Baranczak’s essay comments on the fall of the Berlin Wall. It was so long ago that I don’t remember why the material copied into my notebook beneath the wedding karaoke scene fails to mention Baranczak's argument, or to inventory his claims.

Instead, my notebook preserves the entirety of his asterisk:

After 45 years of communist rule, Polish artists and writers will soon find themselves in a position similar to that of their counterparts in the West: free to express any view they wish, they may find that such freedom makes words lose their weight. They may discover that amid the multitude of voices an important message will go unheard. Subject to market laws, serious thought and innovative experiment may be elbowed out by cheap entertainment and easy convention.

7. The transubstantiating asterisk

—But none labors as rigorously as the transubstantiating asterisk.

In The North China Lover, Marguerite Duras uses asterisks to append the text with continuous instructions for a cinematographer, specifying how the scene should be shot. Reading the asterisks transforms the nature of text; the book becomes a movie in the mind; the asterisks are the only way into this.

“Her face is already the ruin it will be for the rest of her life," Duras tells us of the young girl who the older man loves. Like a statue, the image of the ruined face creates a plaza around it, or a textual space which requires the reader to stop. To look up. To see how the author looks at herself from a distance.

On the page which precedes the ruined face, Duras offers the following asterisk:

Shoot the sleeping lovers. The Book As Pulp Novel. And shoot the weak, sorry light from the street lamps.

I imagine a camera shot of her looking in the mirror and flashing back to that child’s face, the child inside the adult who has discovered what desire does. It's not that the asterisk prevents the characters from being misread — Duras knows they will be misread, for the author is already a failure by social standards, which is to say, she is the woman who knows the ruined child inside the statue, the creature whose sexuality cannot belong to her given the reader's need to interpret it — the reader is the one who determines what the author says.*

Annie Ernaux also leans on the transubstaniating asterisk in Simple Passion. But she uses a modified asterisk— a faint, modified crucifix-like shape—in order to disclose how her writing process is challenged by the temporality of romantic love.

"I am still in the age of passion… But it has changed, it has ceased to be continuous," Ernaux writes, just before adding her makeshift asterisk to modify it:

For want of a better solution, I have switched from the past to the present, although it is impossible to establish the demarcation line between the two tenses. I am incapable of describing the way in which my passion for A developed day by day. I can only freeze certain moments in time and single out isolated symptoms of a phenomenon whose chronology remains uncertain – as in the case of historical events.

I'm not sure what Ernaux's tiny cross signifies—whether it is a gesture towards iconography, the religious stops along the route of the passion, or time out of time—but it changes the way the book is read by renaming the details of the love affair as in the case of historical events.

7. The asterisk that ghost us

Again, the day’s events sneak into my notebook via a gathered meteorite from Yourcenar's Piranesi that wants to be the threshold into a poem about ruins:

To indicate at once

this mixture of the exquisite and the mediocre,

I placed a blouse over the window —-

And something in the beginning of this poem takes me back to one of the first sonnets I ever submitted for publication— a sonnet that was rightly rejected again and again—-over a decade ago. It was one of those poems that grows from an image painted by a word or an idiom, wherein the idiom amplifies unseen threads between your current obsessions and your nightmares, and the history that is ‘family’.

There: the Judas slits. Metal prison doors have peep-holes which guards uncover to check on the prisoners. Known colloquially as “Judas slits”, these holes provide a slatted, diminished view of the prisoner which reflects their position.

"The wall of my uncle's prison cell had two small shadows that were shaped like stars," my father said.

Related to the thin shaft of sunlight near the floor, the two stars tracked a daily route around the room, like a timekeeping device that made up for the absence of clocks, watches and windows.

"Time went on forever at Aiud," my father adds, brightly.

"The dandelion is an asterisk on a stalk, its grammar cast in the optative mood," writes Dan Beachy-Quick.

I ogle the gold tinfoil object at the top of the holiday tree that sits on the boundary between the earth and the numinous. It's funny how fallen stars get mounted as symbols.

Every asterisk challenges the temporal flow of the text. Every cenotaph has an asterisk for a heart. *