THE ALBUM

Serge Gainsbourg’s Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971) is twenty-eight minutes of seamlessness stitched from shared riffs and melodies that return in swirled variants and disjunctions. Gainsbourg collaborated with composer Jean-Claude Vannier for this concept album dominated by what Tom Ewing has so aptly called “Herbie Flowers’ treacly bass” with its slow, sweved funk.

Again, Tom Ewing puts it so well:

That bass is the first sound you hear on Melody Nelson, quietly tracking up and down in a windscreen-wiper rhythm: Gainsbourg starts talking in French 30 seconds later, describing a night drive in a Rolls Royce Silver Ghost. The album is routinely described as "cinematic," but the music is more of a mindtrack than a soundtrack—-a tar pit of introspection when Gainsbourg's brooding narrator is alone at the record's beginning and end, then giddy and savage by turns as he conducts his affair with the 15-year-old Melody across the short tracks in the album's middle.

Although Gainsbourg abandons his archetypal vocals in it, replacing them with a fuzzed breathiness, accomplished by drawing the mic close to the mouth, there is an intersection between myth and modern in it, a supple paean to Baudelairean decadence.

I think of line-breaks often when listening to this album because of the way it uses space and breaks to create a series. The music veers from freewheeling guitar, funk style bass guitar, spoken-word vocalizations, and lush, deep orchestrated string and choral arrangements by Jean-Claude Vannier who composed almost the entire music in collaboration with Gainsbourg for the album.

There are seven songs total, and the first and last songs are the longest, both running close to seven minutes and forty seconds a piece, built around the same bass lines (though Gainsbourg brings in a Greek chorus to round out the final song). It’s ethereal, funktastic, buzz-pocked, and trip-hopped.

Melody 7:37

Ballade de Melody Nelson 2:01

Valse De Melody (Version Instrumentale) 1:32

Ah! Melody 1:50

L'Hotel particulier 4:06

En melody 3:27

Cargo culte 7:41

Serge Gainsbourg does vocals and composition, while Jane Birkin enters as the persona of Melody, and carries those vocals. Alan Parker plays the electric guitar. Dave Richmond and Herbie Flowers play the bass guitar. Dougie Wright does the drums. Jean-Claude Vannier plays the piano, organ, harmonium, and cymbals. A French youth choir provides the choral voices at the end. Jean-Luc Ponty plays haunting violin parts.

As for influence, the album has “officially” touched musicians and songwriters from Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker, Beck, Tricky, Air, Faith No More, Broadcast, Massive Attack, David Holmes, Cibo Matto, Portishead, Stereolab, Michael Stipe, and Neil Hannon.

*

Backstory. Gainsbourg had been writing chansons for a decade, and a feted affair with Brigitte Bardot prompted his most successful song-writing period. But Gainsbourg’s work was still classified as pop, still pop enough to win Eurovision.

For someone who considered himself an artist — and who studied painting before destroying most of his work in a moment of frustration— Gainsbourg did not rest comfortably with popular culture, or the forms of fame it promised. He still considered himself an artist, a mind of multiple mediums, so he vowed to make weighty, dark, novelistic art through the disposable medium of pop culture. He would subvert the sweetness of the chanson by bringing it into dialogue with other instruments and a story. A plot. Enter Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, a book Gainsbourg admired for its relentless darkness. Darran Anderson says what fascinated Gainsbourg about Lolita was how it revolved around “the narrator, the male ego and all the obsessive, destructive decadence and delusion therein”:

Like the book, it is an album about the Beast, masquerading as a study of the Beauty.

*

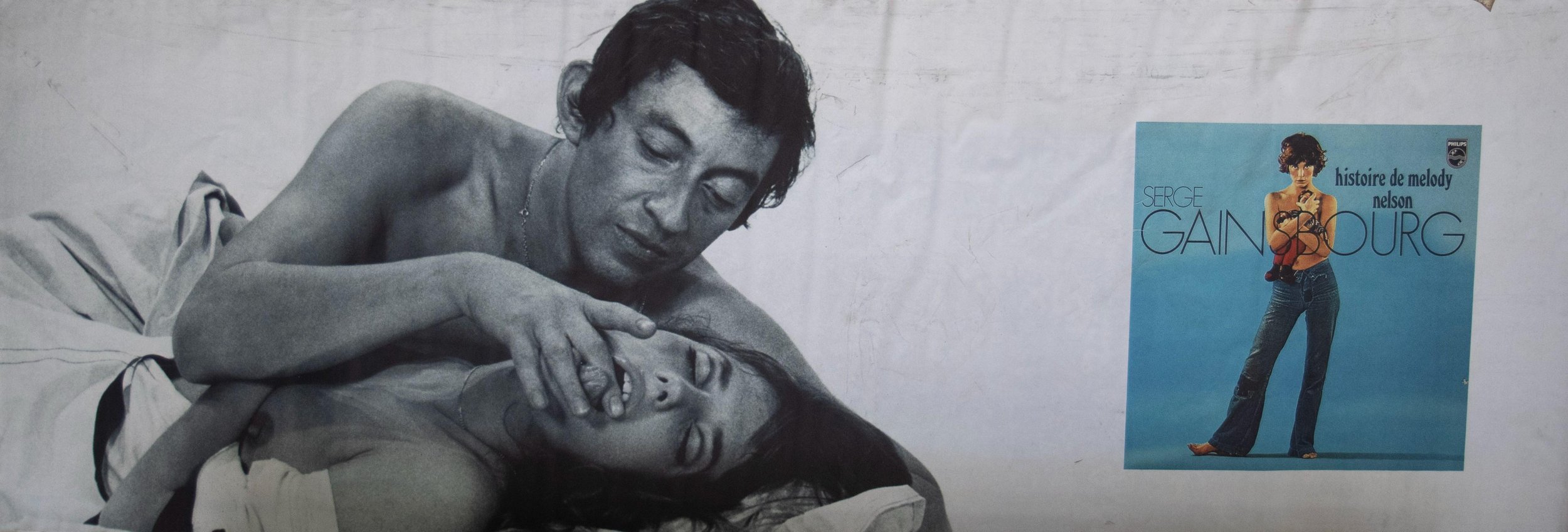

Three years before this album, Gainsbourg met Jane Birkin on the set of Slogan, in which he played a rather louche Frenchman who falls in love with the attractive English lead, played by Birkin. The May ‘68 riots changed the air in Paris. Gainsbourg and Birkin fell in love. And so it began — a romantic and creative partnership whose duet, “Je T’aime…Moi Non Plus”, was quickly banned in both France and England. In 1970, Gainsbourg imagined the form he thought could carry his obsession for Birkin, and this form leaned into a cinematic score, an album which alternated between words, music, songs, images, and metafictional traces.

Jane Birkin, who had become Gainsbourg’s wife, served as both image, sound, and inspiration: she is on the cover art of the album; she provides the voice of Melody Nelson. The metafictional plot begins with the middle-aged male narrator driving his Rolls Royce Silver Ghost along a road at night, until he accidentally knows a teenaged girl off her bike. This is Melody Nelson, a young British girl, whom the narrator rescues and then takes to a hotel, where they have sex. The music carries us through this strange, sudden love affair with short asides and conversations between the couple. When Melody catches a plane back to her family in England, the male narrator is heartbroken, devastated. He performs an African Cargo Cult ritual in the hopes that it will cause his love to return. But magic doesn’t always do what we want— the threshold it crosses alters everything— and we are given to understand that the ritual causes a plane crash, presumably the plane carrying Melody home.

Gainsbourg had recently read of the African cargo cults that prayed for Western-built planes to crash on their land, believing these technological wonders to be gifts from the gods unfairly bestowed upon the wrong people. In order to keep his and Birkin/ Melody’s love pure, he decided, she had no choice but to die by his hands (fictionally-speaking). As an ode, bonkers; as an honest outpouring of one man’s obsessive love, timelessly fascinating.

Why does the cargo cult ritual cause the plane crash? Is it because the male narrator appropriated a ritual whose mastery he couldn’t claim? Does it reflect his subconscious longing that the beloved should die rather than be permitted to leave? Does the plane actually crash or is this part of the story the narrator offers to end his feelings for the beloved —to close the narrative?

Aside on Benjamin Biolay’s “Dans Le Merco Benz”

Before laying out Gainsbourg’s album, I want to note something that has always struck me, and yet elides most commentary on Benjamin Biolay’s early work, namely, Melody Nelson’s influence. Biolay definitely borrows a little in his video for “Dans Le Merco Benz”, which stars Chiara Mastorianni, his then-wife, whose voice also provides background choral vocals. Unlike Gainsbourg, Biolay focuses on the vehicle itself, the Mercedes Benz that has replaced the Rolls Royce as the car of European luxury.

Melody 7:37

The video for “Melody” was created by Jean-Christophe Averty, and it ran as a TV film in France produced several years after the album’s release.

Jane Birkin plays Melody both vocally and visually in this album. You can watch this “Melody Nelson,” where Jane Birkin joins as a background voice and the character. The background is critical. Melody is Serge’s invention.

The ballade form here begins with a conversation between Gainsbourg and Melody in spoken word, which then shifts into melodic chanson form, with Melody’s voice serving as a soft instrumentation rather than a vocal. Here’s a translation:

HE: This is the story of

SHE: Melody Nelson

HE: Apart from me, no one ever held her

in his arms

Does this surprise you?

So be it.

She had love, poor

SHE: Melody Nelson

HE: Yes, she had tons

Though her days were numbered

14 autumns

15 summers

And it continues a bit more, to end with the speaker asserting the possessive form — “My Melody”— which he finishes by describing:

Precious little fool

You were the condition

Sine qua non

Valse De Melody (Version Instrumentale) 1:32

Gainsbourg borrows the waltz form to bring in music. And he subverts the stipulation of the title, namely, that this is an “instrumental version,” by singing softly through it— or insisting the voice is an instrument.

Ah! Melody 1:50

A sickness, I don’t know what I offer you.

L'Hotel particulier 4:06

This is where the love affair takes place, in the hotel. The setting. The drums soften the entry but also add layers which feel ominous. (Tom Ewing: “Gainsbourg's voice shudders with lust and dread, and the music responds, flares of piano and string breaking into the song over an impatient bassline.”)

En melody 3:27

Melody voulut revoir le ciel de Sunderland

Elle prit le 707

L'avion cargo de nuit

Mais le pilote automatique aux commandes de l'appareil

Fit une erreur fatale à Melody

Melody wanted to see Sunderland’s sky again

She took the 707

The cargo plane’s night flight

But the autopilot in control of the device

Made an error fatal to Melody

Cargo culte 7:41

In “Cargo Culte,” the final song, the speaker is looking for Melody — and he asks the Sirens where she is — and a chorus of Greek Sirens fills in the space between his spoken word chanson-style monologue. And repetition structures the mythos of the album: “Cargo Culte” returns to the melodies and motion of the first track, “Melody,” adding only those wordless chorales to dampen the return.

The montage of antiquated objects, the peripatetic searching, the drive to find Melody among curiosities form part Gainsbourg’s aesthetic in this album.

Jason Draper described its tonal energy best: “The closing Cargo Culte alone rises to such intensity, it’s virtually impossible to hear it without picturing Gainsbourg plunging the knife into his own heart before stabbing a Gitane out in the wound.”

The Making of Melody Nelson

Turning Jane Birkin into Melody Nelson was its own art. Belle Hutton explains how Melody’s red hair was prompted by a bad mood:

Gainsbourg was late to set, and when he arrived could see that Birkin had grown impatient. “He opens his briefcase, where he always carries his wads of ‘Pascal’ bank notes and packets of Gitanes, and pulls out an auburn wig – red, really – that he puts on his head to play the clown and make her laugh,” recalls Frank. “Suddenly the atmosphere relaxes. Then Jane tries on the wig, looks in the mirror, and becomes Melody.”

Tony Frank, the photographer who took the iconic cover photos, released a recent “booklet”, Bleu Melody, which includes contact sheets, proofs, behind-the-scenes imagery and slides from the shoot, a series of “Melody mementoes.”

The toy monkey which covers Birkin’s breasts in the cover photo was a personal treasure, a toy given to her as a child after her uncle won it at a carnival.

Tony Frank says that Birkin carried this monkey —her “Monkey”— everywhere in a large wicker basket that she used as a purse. Legend has it that Monkey wound up in Gainsbourg’s coffin after his death. It was Jane’s final gift to him.

Realizing that he’d created a memorable monster, Gainsbourg named his publishing company Melody Nelson in honor of his fictional muse—- but then got distracted, producing a new album of unremarkable acoustic songs that feel uncomfortably safe in comparison.

Tom Ewing notes that “Herbie Flowers, whose bass is the undertow pulling the album together, surfaced a year later playing on Lou Reed's "Walk on the Wild Side", whose bassline is the first ripple of Melody Nelson's wider pop culture influence.”

“Since then it's been left to others—- Jarvis Cocker, Beck, Tricky, Air, Broadcast—- to pick up this record's breadcrumb trail,” Ewing adds. “But Gainsbourg's dark focus, and Vannier's responsiveness, aren't easily equalled.

Here’s the video for “Melody Nelson,” where Jane Birkin joins as a background voice and the character.

Live performances & More on Jean-Claude Vannier

Gainsbourg’s partner in composition, Jean-Claude Vannier, also composed for Air, David Holmes, Stereolab, Pulp's Jarvis Cocker, Portishead, and Beck, whose 2002 track "Paper Tiger" from Sea Change is extremely close to the distinctive Histoire de Melody Nelson sound. Vannier has spoken more recently about his experiences with the making of Melody Nelson in an interview.

Vannier performed the album live at London's Barbican on October 21, 2006 with guest vocalists Jarvis Cocker, Badly Drawn Boy, Brigitte Fontaine, The Bad Seeds' Mick Harvey and lead singer from Super Furry Animals, Gruff Rhys. Vannier performed the album in its entirety alongside his own solo album L'Enfant assassin des mouches. Publicity for the Barbican concert revealed that the musicians used for the album were Dougie Wright, Big Jim Sullivan, Herbie Flowers and Vic Flick who all joined Vannier for the concert. The BBC Concert Orchestra, the Crouch End Festival Chorus and a children's string quintet were part of the show.

In October 2008 22nd & 23rd Jean-Claude Vannier performed the album live at the Cité de la Musique with guest vocalists Mathieu Amalric, Brigitte Fontaine, Brian Molko (Placebo), Martina Topley Bird, Daniel Darc, Clotilde Hesme, Seaming To. Also performing were Herbie Flowers (bass), Claude Engel (guitar), Pierre-Alain Dahan (drums). Jean Claude Vannier also performed the L'Enfant Assassin Des Mouches. The Lamoureux Orchestra, the Yound Choir of Paris and a children's string quintet were also part of the show.

On August 28, 2011, Jean-Claude Vannier participated in A Tribute to Serge Gainsbourg at the Hollywood Bowl. The artists that performed Gainsbourg's songs that evening included Beck, Sean Lennon and Charlotte Kemp Muhl, Mike Patton, Zola Jesus, Victoria Legrand (singer of indie band Beach House), Ed Droste (singer of indie band Grizzly Bear) and Serge's son Lulu Gainsbourg. The second half of the evening included a performance of the album with Vannier conducting. Each of the album's songs were performed by different combinations of the evening's artists, backed by the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and the Cal State Fullerton chorale. American actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt also participated in the album's performance.

On an interesting side-note, Lulu Gainsbourg now lives in NYC, and swears never to move back to France. But he has covered a number of his father’s songs, including Melody.