“I made him promise he'd piss on my grave,” Edmund White wrote of the lover who broke his heart.

The week bumped over the hump that was Tom Waits’ birthday, and certainly the lyric “Who are you this time?” came to mind as I let Edmund White’s memoir, My Lives, devour me.

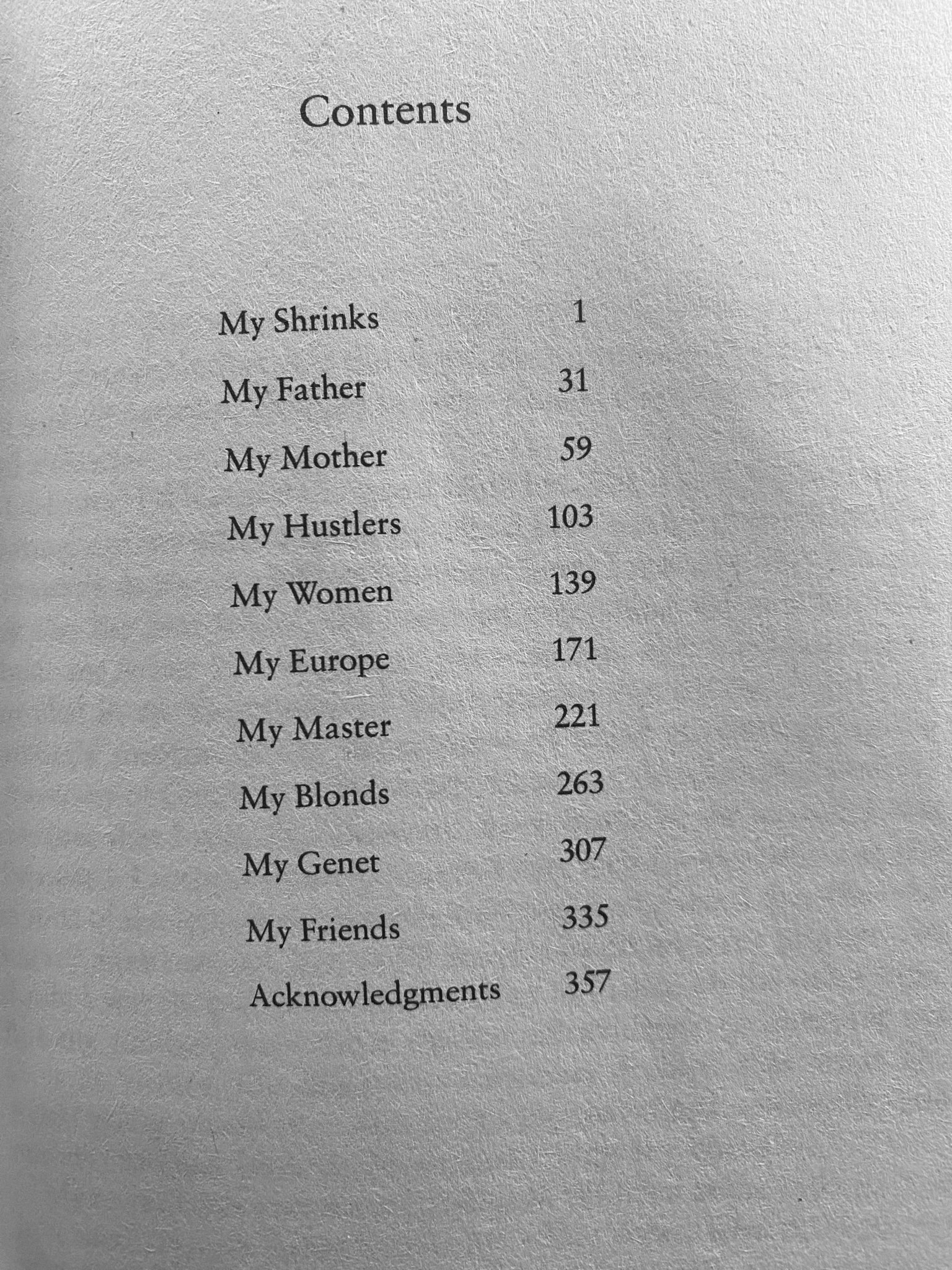

The conceit of White’s “lives” is that he inventories them.

If the table of contents enumerates the ten lives that Edmund White lived, the text refuses any assumption that these lives are separate from the one he is living as he writes about the Others, as he welcomes his Others into the fold of selfhood.

Oddly, like the writers associated with New Narrative, White wants to reclaim “realism” rather than abandon it.

He wants a shift in how we describe “reality”.

Ideally, maybe really, such a shift shift would enable us to acknowledge the way reality differs from our discursive approaches to representation.

I made him promise he’d piss on my grave seems like the perfect vow to exchange with a human one has loved when leaving. It is an alternative eternity, an intimate and forbidden homage, a vow closer to standing outside time than trying to tame it.

“This is realism, I thought with grim satisfaction.”

Identifying as a “mystical atheist,” White recounts the spiritual seeking of his adolescence (encouraged by vaguely Christian Scientist mother). Already, he holds realism in high regard as the measure of value.

I'd gone every afternoon for weeks to the neo-Gothic library at Northwestern to read Max Müller's Sacred Books of the East. I'd dipped into the Torah, the Koran and the Upanishads. But Id been gripped by the Buddhist sutras. No matter how pessimistic I might become, I could never begin to approach the extent of Gotama's nihilism. He saw the self as an illusion, desire as the root of all evil, rebirth as the worst of fates and extinction as the only goal. In this world the most and the least one could expect was sickness, old age and death. Whereas the Hindus posited an irreducible soul, the atman, the Buddha preached the doctrine of 'no soul,' anatta. In an unpeopled universe full of nothing but illusion and suffering, not a single entity existed, certainly no deity.

This is realism, I thought with grim satisfaction. No interceding ranks of angels, no accountancy of sins and good deeds, no heaven nor hell, no nosy-parkering into other people's bedroom hijinks. The opposite of hateful, intolerant Christianity.

And all is divine until White and his mother get to the Chicago Buddhist Church in a rundown South Side neighborhood nearly thirty miles away. There, in that Church, they “encountered a group of smiling, waving Japanese men, women and children worshiping Amida, the Lord of the Western Paradise, a personage very much like a Catholic saint.”

He was a bodhisattva in the (to my eyes at least) 'degraded' form of Mahayana Buddhism, someone pledged to stave off the horrors of rebirth and the bleak solitude of nirvana by spiriting his followers away to a paradise where they could struggle toward enlightenment in comfort and in the busy, bustling society of likeminded souls.

“I was bitterly disappointed - by the organ and hymns that sounded suspiciously Methodist, by the flutter of arriving parishioners in big hats exchanging kisses, by the depressingly secular announcements of upcoming bingo games and covered dish suppers,” White says. Bitterly disappointed, he fled the scene.

Disappointment being the gap between what one expects and what is delivered, White inventories his losses:

Where I'd expected a bald abbot stony with meditation, a trickle of sandalwood smoke and a superb indifference to all forms of striving, I'd found a congregation of ordinary folks besotted in the ordinary way with the little pains and little rewards of everyday life.

'I thought it was nice, Mother said, puzzled by my contempt.

You liked it because it was just like some dismal Christian service,' I said nastily.

Contempt, nastiness, spiritual disappointment, aesthetic disaster: the affective expressions clamber over the material disenchantment in White’s telling.

“Even these humiliating occasions when I was robbed could be used as material. Life was a field trip. My writing would turn all this evil into flowers.”

White writes his hustlers gorgeously, engorgedly, edging close to the realism of New Narrative.

“I was always reading novels, and I knowingly chuckled when a character was described as 'foolish' or 'naïve' but here I was: I was naive, I was foolish, which until this moment I'd never suspected,” he acknowledges, before pivoting to muse on craft:

The reader considers himself to be all-knowing, superior, but now I had to push this conventional flattery aside and recognize that cleverness is not a question of perspective but of accumulated experience in the world. I was slowly putting together my own fund of lived worldliness, more modest but more real than the reader's omniscience.

I was duped again in Cincinnati that summer when I was eighteen. I gave a hustler forty dollars to buy us both one-way Greyhound bus tickets to New York. Our plan was to meet on the corner near my father's new house in Watch Hill, an area of big estates and no sidewalks where any pedestrian, especially a teenage boy with a suitcase, would have attracted attention if anyone had been awake and driving past. I spent a sleepless night imagining how I'd become a blond with the bottle of peroxide I'd put in my bag; I'd be so transformed that my father would never be able to find me, neither he nor his private detectives. Kay, my stepmother, would go to awaken me and find my room empty. No note. A missing suitcase. A drained tub and a wisp of winking foam from my dawn bubble bath.

The guy never came. The hot, steamy Cincinnati sun rose and became more intense, like an alcohol lab burner concentrating and flaming whiter and whiter. I felt so foolish. I was grateful I hadn't already dyed my hair. Then for a second I'd become hopeful again and imagine he'd been held up and would appear in another minute or two if I would just be patient. Then I would remember how uninterested he'd been in the directions to this exact corner - at the time I'd thought it was proof of his quickness that he'd been able to grasp the baffling directions so easily. At last it came to me with pitiless clarity that he was a con man. He'd conned me. He'd tolen wow money and run. How he must have laughed at my naivety. When I saw him on the Square, a few nights later, he waved merrily.

One could learn about life from literature - one could learn to spot a confidence man - but only if one woke up from the smug, dreamlike superiority of the reader, which blinded one to the actual slippery manifestations of vice and dishonesty in the shadowy world of reality. In the novel, at least the reassuring nineteenth-century novel, one was always privy to everyone's well-lit motives and alerted to even the first sign of corruption. But in life - how could one navigate in an unnarrated world? Of course I was always narrating my life to myself but unfortunately I had no access to the private thoughts of the other characters around me. Even my own mind was too prolific to be comprehensible. It was certainly true that I was fashioning the book of my life at all times, trying out sentences, sketching out plot lines, hoarding impressions, restaging the scenes I'd just lived through. I'd already written and typed two novels in boarding school, one about me and the other (my senior thesis) about my mother or some more driven version of my mother to whom I attributed my own sexual obsessions. At every moment convinced myself that I was gathering material for the novel of my life - all experienced from the philosophical distance of the author.

Yes, White confirms: “Even these humiliating occasions when I was robbed could be used as material.”

For: “Life was a field trip. My writing would turn all this evil into flowers.”

And his “sexual obsessions” were not merely obsessive; they also partook of curiosity. “All these encounters with hustlers were as much an expression of fear as of desire, and above all they were animated by curiosity,” he writes. It is a feast, a communion, a religion to replace the failed spiritualities:

I was swallowing the sperm of strangers and this feast convinced me I was possessing all these men. I was like one of those nearly insane saints who must take communion several times a day, who are driven by a desire to eat the body and drink the blood of a long-dead historical human being. That man may also have been a god, but the saint longs for the pulse and crunch of a thirty-three-year-old Jew nailed to crossed boards. In the same way I had this permanent, gnawing hunger for all these street-corner Hanks or Orvilles, for their penises fat or thin, crooked or straight, eager or reluctant.

Impossible not to think of Robert Gluck’s descriptions of cruising the bath-houses here. Hopefully that Gluck review will get published soon, but who knows?

“My Roberto (my hustler and my character) was quiveringly and richly fleshed, his smile soft and unfocused, his body instinct with laughter.”

His first muse was a hustler who went by the name Roberto:

The room was big and clean and the wide window looked out on the square below, and afforded enough illumination so that we didn't need to turn on the overhead light. In the half-darkness his white shirt glowed. He let me unbutton it as we kissed. As soon as we began to touch, Roberto had the sort of gleeful, complicitous smile that says, "Look how wicked we're being." Never before had associated irony with sex between men. For a moment I even suspected that Roberto might be gay or bisexual and surprisingly! still found him attractive. He held my naked body against his and quaked with silent laughter, then moved without transition into long, languorous kisses, letting his eyes rise and wander along the line between the ceiling and the wall.

Roberto's white shirt and tanned skin, his compact body with the sensual ass, his sense of irony and romantic air - all these properties came together to inspire me. That fall I wrote a novel about him while I was in my junior year at the University of Michigan. Like many novels by young people it was derived more from my reading than from my experience, but the character of the younger brother 'Roberto' was based on my very own Lafcadio, my own Tancredi, my own Felix Krull, my own Fabrizio. I had in mind a synthesis of all these gallant young men from Continental literature, plucky characters who had as strong a sense of personal style as my hustler, who were as romantic and long-lashed as a silent movie star and as streetwise as a Neapolitan shoeshine boy.

My Roberto (my hustler and my character) was quiveringly and richly fleshed, his smile soft and unfocused, his body instinct with laughter. I knew almost nothing about him but I could keep returning to my memory of having held him in my arms for a moment, and having rented an hour of his time and leased on short term the use of his torso and hips and lightly downed legs and tan arms flung back to reveal his soft, creased, axial paleness. I liked the notion behind the English term rent boy more than our hustler, since the American word suggested something dishonest and on the make.

Roberto was my first male muse, a mental snapshot I worked up into a full-dress portrait in oil. I wanted to recapture that moment I bought and present him with a portrait in words. I wanted to convey to the reader as well my fascination with the boy. I was like Caravaggio, who paints in a saint's halo behind the curly head of a street urchin with a farmer's tan and a cynical smile. In my novel an older, richer, blonder brother hires a darker, smaller kid - and discovers they are half-brothers, the offspring of the same father but of different mothers, one fair and legitimate, the other an Italian mistress.

That the book, itself, did not rise to the level of Roberto’s mystique doesn’t matter. In the novel White calls his “failed fantasy,” the fact that the narrator’s first encounter with Roberto was commerical didn’t prevent it from being rapidly “elevated to brotherhood and, finally, impossibly, to an almost marital love.”

“The title of the book was The Amorous History of Our Youth, a pedantic fusion of Lermontov's Byronic parody, A Hero of Our Times, and of The Amorous History of the Gauls, a seventeenth-century satire of the court by Roger de Rabutin, Count de Bussy, which caused this sharp-tongued cousin of Madame de Sévigné to be banished to his comely little château in Burgundy,” White confesses in that wry (and very precise) whisper that gives away the snob.

“The most poignant moment in Lady Chatterley's Lover occurs when, unannounced, her ladyship visits the gamekeeper's cottage and sees him, all unawares, washing himself in an outdoor shower.”

Like a lover worthy of his novel, White looked for Roberto on the streets the following summer—-and every other time he wound up in Chicago—but he never found him again. All that remains of Roberto is the whiff of a hot ghost in White’s convoluted, breathless, Brodkey-tuned sentence structure: “Pedantry, satire, literary ostentation, an irritating lack of sincerity - none of these faults could conceal from my eye, at least, that I was quite humbly and gratefully in love with an Italian boy I had met once who had a strangely low and almost strangled way of whispering his words into the big ear of a bespectacled American geek, his awestruck client.”

Roberto’s “awestruck client” quickly pivots into one of the self-lacerating statements that characterize his essays when White adds, “If in my novel inappropriate emotions kept firing off, all these missteps just revealed how inadequate I was to the occasion.”

True to life, true to literature, White admits the men he picked up on Times Square weren’t quite sublime. Nor were the tricks erotic. The reality lacked the heat of his fantasies because “some of these boys were too perfect”:

I liked a flaw, a wound, which acted as an opening to the communion of shared humanity. For instance, a guy named Hal lived upstairs from me and sometimes he'd drop by for sex. He had a badly mended harelip which made his taut, muscled torso and hairy chest and pale, narrow loins seem vulnerable, touching.

The most poignant moment in Lady Chatterley's Lover occurs when, unannounced, her ladyship visits the gamekeeper's cottage and sees him, all unawares, washing himself in an outdoor shower. She glances at his white, narrow hips and his thin back and he never realizes she is there. His back, so pale and thin, is wholly male and vulnerable. If, instead, a big blond showboat, perfect with a blinding smile, an ever-ready penis, came bounding up my steps, his very perfection made me feel somehow . .. orphaned.

“Young and attractive," in his thirties, White frequented the gym thrice a week, hoping to make a good impression on the johns. But the johns had other affinities, which the author analogizes to figures in a passion play or religious iconography:

That “suitable vague” St. Theresa: abject.

“Now, I'd say to myself, I'm going to write a good page.”

While employed by NYU’s New York Institute for the Humanities, White sat in a windowless cubicle and attempted to write his “novel, A Boy's Own Story, fighting the anxiety I usually felt when I wrote.” He details the writing process, the craft, if you will:

The heat and my hangover tempted me to put my head down on my desk and fall asleep. I was so sleepy I would write portmanteau words, which collapsed the syllables of two or three words I'd already sounded in my head. I even started to spell phonetically. My clothes would stick to me. I'd sigh and shift in my chair from one side to the other. One more trip to the water cooler. I'd come back and read through my latest pages and make microscopic changes. I'd sprawl on my desk. Then I'd get fed up with myself, sit up straight, as tall as possible in the chair, and I'd hold my pen as if it were a scalpel. Now, I'd say to myself, I'm going to write a good page. Usually my head was so fuzzy with the morning-after effects of wine and marijuana that I was pleased if I could form real sentences, nothing more.

"I would be horny, if that meant lonely, and anxious to such a degree that only sex could lift me out of this mire with enough immediacy and absoluteness," White says of the intervals between thinking, imagining, and writing.

“ . . . I had no notion that some people were more popular than others, much less that there were acquirable techniques to insure popularity.”

Adolescence introduced him to social scripts and revealed the strange theatre of American dating and gender performance to White. “In that paradise before I bit into the apple of social awareness, I had no idea that one could be ingratiating, seductive or even more or less likable,” he writes. He lacks the MBA techniques that teach humans how to fashion life.

I hadn't yet learned to ask flattering questions, to lead people out, to express sympathy for their pain and encouragement for their pleasures, to exonerate their failings as 'normal and declare their modest successes to be triumphs.? I am sure I was a nice enough guy and even projected a low wattage charm, but whatever glow I gave off was just the crumbling half-life of my sluggish existence. In the same way that I had no idea what I looked like and managed to stumble around ill-shod, badly dressed, unkempt and often dirty, I had no notion that some people were more popular than others, much less that there were acquirable techniques to insure popularity. Boys and girls alike were for me something like human furniture filling up rooms and corridors, as featureless as the real furniture we lived among. Just as we didn't notice the faded flowered slipcovers on sagging couches or the armchairs on which the green plush was worn down in browning patches, so we didn't see this kid or that as magnetic or repulsive. To be sure, I did fall under the physical spell of a Buster or Howie or Cam, but it seemed like a miracle if one of them liked me back.

“It never occurred to me that friendship was biddable,” White concludes.

“We revered Brecht, not Marx; Mayakovsky, not Lenin; Lotte Lenya, not La Pasionaria; both Ingmar and Ingrid Bergman; Elizabeth Taylor the actress and Elizabeth Taylor the reserved English novelist.”

He recollects the tanginess of his early New York friendships. “We arty types, especially the theater queens, were in the middle room, as if we were the intermediate sex,” White writes:

We were neither scrubbed and perky like the Greeks, nor alienated and uncombed like the Beats. We drank but didn't smoke pot, we had nothing resembling a credo beyond a faith in the permanent avant-garde. We revered Brecht, not Marx; Mayakovsky, not Lenin; Lotte Lenya, not La Pasionaria; both Ingmar and Ingrid Bergman; Elizabeth Taylor the actress and Elizabeth Taylor the reserved English novelist. Ten years later and the idea of High Culture would begin to crumble, battered by the American cult of success and the distinction-dissolving ironies of Pop Art. But in the late fifties we still believed in honorable poverty. We still thought that beauty should be difficult, that incomprehension was a first necessary step toward initiation and that time would determine irrefutably which of our current artistic developments had been the one, the only, the inevitable next one.

“I wanted to immerse myself in him, just him, his ideal essence, just as a tomb sculpture in Renaissance France always shows its subject at an ideal age, thirty-three…”

Recollecting his adoration of Stan during his senior year in college, White describes his singular project as "Stanley, seeing Stan, courting him.” For love keeps us riveted, busy, anticipatory. “Love gives us something to do,” he writes. “It ties our days together, as if a composer had linked all the elements of the score with lightly curving legato marks, swooping from note to note like telephone wires.”

The image of Stan dressed in white on that stage never leaves White's imagination. Stan remains in that "slow-paced, deeply internal performance," animated by his own mesmerization, "as if he were slowly fermenting his own essence and getting drunk on it."

I, too, felt a bit drunk upon reading White’s tomb-analogy, burying my brain in this possibility of memory as a formal gesture that entombs while also provides the image for the iconography. “I didn't want him to be someone else, to impersonate a character,” White says of his Stan on the stage, “I wanted to immerse myself in him, just him, his ideal essence, just as a tomb sculpture in Renaissance France always shows its subject at an ideal age, thirty-three, and whether the subject died much older or younger, he must be presented as he will appear in his perfect form at the Resurrection.”

“You should hold my hand and go through this with me.”

One of his masters was also the man who broke his heart. Like the BDSM wired into their relationship, the breakup leaves White in the masochistic position. He has never felt so powerless. He weeps in his university office. He tells other professors that he doesn’t know if he can get over this. Eventually, he meets up with T, the lover, again:

It was April 12, 2004. He had on my favorite cerulean blue T-shirt. We sat knee to knee and ate beside the bar. The waiter was so solicitous, I could almost say tender, that I felt he knew this was a reconciliation. I told T Pat sarted seeing a middle-class shrink who was 'sure" T must have fet degraded and objectified' by being paid.

T: I didn't mind being paid for something I wanted to do, that was hot, earning money like a hustler, but then when I stopped wanting to do it, I resented the money."

T: I knew I wanted you to fall in love with me because I wanted to be part of your life. And, admit it, if I hadn't slept with you, you never would have thought about me twice.'

T said: 'I didn't want to feel I had to go to bed with you just to please you. That's too much like when I was a kid with my mother. I felt that if I didn't please her my whole life would fall apart and I'd lose everything. I don't want to have sex or do anything just to please someone else.'

In dialogue with T, White gives offers himself as abject, feminized self —- apologetic (I said I was sorry I was being so neurotic, crying all the time and plaguing him with my neediness.); cautious and ego-affirming (Well, the good thing is how we're talking.); critical; wounded (I noticed that my love for him had gone from being "flattering to 'a pain in the ass.'); wistful and unrealistic (I wondered if people still fell in love this way, my way. ); comparative; prone to self-diagnosis (Was it a period piece, my love for I, something akin to Sarah Bernhardt's wooden leg?); redemptive (We never talked about this honestly before, not when we were having sex); looking for a route back into a relationship ('It's like you're so strong, such a bully, you can just say matter-of-factly, "No, we won't ever have sex again" - you can say that and I nod, then I go home and suffer and why should I suffer all alone?); indignant; pathetic; (You should hold my hand and go through this with me.); bossy; controlling; pathetic; crumbly; on the edge of a stool that keeps tipping towards tears.

White envies his students who “bumped shoulders, wore each other's clothes, slept in the same bed for weeks without having sex until one drunken night it half-happened, then the next morning it took place fully.” Their casual fatalism had its own momentum: “they drifted away, cried a bit, hooked up one more time and it was over.” A brisk genre. A formal figuration vastly superior to his own “art nouveau passion.”

"Yes," he said, "that's what I believe."

“I had a small but faithful readership, and I had always placed the overall longevity of my talent, such as it was, above the success of any one book,” White says, locating himself among the minor writers.

Reflecting on the value of his own books and the question of whether he will be read, his compares his belief in the “readers in the future” to an “act of blind faith.” [“Of course people would always read things (captions, e-mails), but would they want to read long imaginative or confessional works written by writers in the past, even the recent past?”]

Following this question further, White inadvertently speaks to what it means to "be read", or how the writer approaches the imagined interlocutor by recollecting an interview with “a trendy English critic.” This critic loathed Jean Genet's novels. White’s love for Genet finally wrenched him out politeness.

"Let me get this straight,” White said to the critic, “Do you think works of art wear out? That one generation can't read the books of an earlier one? That Shakespeare has nothing to tell us now?"

The dialogue continued:

"Yes," he said, "that's what I believe."

Suddenly all the pretensions of 'universal and 'eternal' art were called into question. I, who'd long since doubted that a 'canon' of white European male books should be read and studied by everyone, was now being asked to frame a more radical question about the relevance of a work by one generation to the next. We still hailed writers for being as original and profound and lasting as Hemingway or Flaubert, but maybe it was an empty rhetorical gesture. Maybe even libraries had a short shelf life.

No matter. I thought you, the reader of the future, the solitary twenty-year-old in Kansas, might be able to hear my voice, scratchy and bleating as it may be, as we can still hear Caruso's. Like Walt Whitman I want to excite at least one young man not yet born; the kid in Singapore or Salt Lake City who gets an erection at the thought of humiliating his teacher.