Poetry is the language of intensity.

Because we are going to die, an expression of intensity is justified.

— C. D. Wright, “Collaborating”

These words were provoked by a tweet from Matthew Leger which shared the first page of C. D. Wright’s poem, “Approximately Forever”:

Approximately Forever

She was changing on the inside

it was true what had been written

The new syntax of love

both sucked and burned

The secret clung around them

She took in the smell

Walking down a road to nowhere

every sound was relevant

The sun fell behind them now

he seemed strangely moved

She would take her clothes off

for the camera

she said in plain english

but she wasn't holding that snake

The poem doesn’t end here, but these seven couplets reconvened in the music of a poem I’ve been reading. Forrest Gander’s Mojave Ghost is subtitled as “a novel poem” traversing the geological features of the poet’s birthplace. In the process, Gander makes the lyric a site of encounter. Interior landscapes blend with exterior landscapes; outside and inside commingle; desert colors evoke the memory of an interlocutor resembling C. D. Wright, who was Gander’s wife (and whose death occurred from a similar cause as my mother’s, around the same time).

Time — geological time, lived time, human time, historical time — is thematic to Mojave Ghost:

The oldest extant pigment of color, scraped

from rocks beneath the desert,

is a flaming pink

Spring comes. It breaks into me. You

break into me.

While the past goes on lifting out of itself like a wave.

But you had the sense to linger by the shore

as I snorkeled out over the nebulous,

slo-mo, shark-eerie drop off

of the shelf.

Across the page of the book, the poem’s speaker pivots between this direct address of a “You” and a more general third-person description. There are no transitions or titles to mark these turns from addressing to narrating, from invoking to telling:

He's seduced by an intelligence that outleaps his own.

She's funny. Her jokes

become his. And she adopts

certain gestures from him

into her vital movements.

Each is charged by the charge in the other.

Each summoned to what

if not a sacred assimilation.

The moments brim with her liveliness. He's

aching to see all the colors in her spectrum.

And her ass, like two cloves of garlic.

After all they've undertaken and lived through,

have they effaced one another's outer limits?

Everything seems the same. The Pacific

chorus frog in the front yard is answered

by the one in the back. The firebox remains

clammed shut. Don Mee's green birdhouse

hangs from the limb of the olive tree. Only now

it is all quivering. Holding its breath.

When they pass in the morning in the kitchen,

he spins her around and kisses her.

As though in response to the question:

How do you answer for your existence?

I couldn’t resist imagining the green of Don Mee Choi’s birdhouse as brighter than the olive from which it dangles. Like the speaker, I acceded to “aching to all the colors in her spectrum” — and heard them in tatters or pieces from Wright’s own poems, the blues of her flowering vines, the hues of her own blooming landscapes:

Imaginary Morning Glory

Whether or not the water was freezing. The body

would break its sheath. Without layer on layer

of feather and air to insulate the loving belly.

A cloudy film surrounding the point of entry. If blue

were not blue how could love be love. But if the body

were made of rings. A loose halo would emerge

in the telluric light. If anyone were entrusted to verify

this rare occurrence. As the petal starts to

dwindle and curl unto itself. And only then. Love,

blue. Hallucinogenic blue, love.

That “loose halo . . . in the telluric light” . . .

Gander evokes these reflections and glimmers from Wright’s poems epiphanically. He grieves and reconceives his love for the one who opened (opens?) a part of him. I hear it in his “audible sunlight”:

I admit: all my gestures are addressed to you. You,

the starting point, the rhapsodic precedent.

Even now, these years later, I'm still

turing my head, listening for your words.

know I imagine them into being, there

being nothing else I can imagine.

In photographs taken of me before we met

I see only the impending joy in my face.

Audible sunlight, the western meadowlark's opera.

And each dawn, your sing-song greeting to the cat.

As if our happiness had its own desire,

the desire to trill, to cling to us, to stay.

Just as I hear an echo of Wright’s love for language in the trilling and the vine-cling.

“I love that a handful, a mouthful gets you by, a satchelful can land you a job, a well-chosen clutch of them could get you laid,” wrote Wright.

A handful. A mouthful. A satchelful. A clutch. The sound of a stick-shift in a truck carrying lovers across the American highways and byways.

At several points in his book, Gander mixes narration and invocation, making it difficult to tell one from the other:

You are the love of my life.

No. You are the love of your life.

Did he keep his word, or only his skepticism?

From the lake's edge, his eyes remain fixed

on an indeterminate wake. What is it

swimming just under the surface?

One from the other is a hard tale to tell, and echoes are infinite. Echoes insist on the trail of sound winding from a distance. I remembered how Wright insisted on meeting the “unplaned” surface as a possibility in a different poem:

Lake Echo, Dear

Is the woman in the pool of light really reading or just staring at

what is written

Is the man walking in the soft rain naked or is it the rain that makes

his shirt transparent

The boy in the iron cot is he asleep or still

fingering the springs underneath

Did you honestly believe three lives could be complete

The bottle of green liquid on the sill is it real

The bottle on the peeling sill is it filled with green

Or is the liquid an illusion of fullness

How summer's children turn into fish and rain softens men

How the elements of summer nights bid us to get down with each other on

the unplaned floor

And this feels painfully beautiful whether or not

it will change the world one drop

From Mojave Ghost:

Oh no. I see suddenly

that what I've caught in my trap

is the favorite hunting dog

of the God of Excoriation.

And everything is scarcely moving

like the mirage of a lake.

No one bears tragedy. It holds you in place.

Indisputable, they say. Two

plus two equals four. As though

reason unlocks truth,

the logic of the universe. But

for some, two plus two

equals many. Which isn't less true.

To reach for a world

that is out of reach.

What seest thou else in the dark backward?

At this point, I pause in my reading. The sparkles and greens of Wright’s Luciferian poem, “Morning Star”, interpose themselves, mid-page, disrupting the flow. And so I quote from the poem by Wright, if only to banish it so that I can return to the question and its “dark backward”:

Morning Star

This isn't the end. It simply

cannot be the end. It is a road.

You go ahead coatless, light-

soaked, more rutilant than

the road. The soles of your shoes

sparkle. You walk softly

as you move further inside

your subject. It is a living

season. The trees are anxious

to be included. The car with fins

beams through countless

oncoming points of rage and need.

The sloughed-off cells

under our bed form little hills

of dead matter. If the most sidereal

drink is pain, the most soothing

clock is music. A poetry

of shine could come of this.

It will be predominantly

green. You will be allowed

to color in as much as you want

for green is good

for the teeth and the eyes.

(I suspect Gander knew Wright’s ghosts well, and befriended them, including the shade of Frank Stanford whose death compelled Wright to reckon with loss, poetry, and inheritance early in her life.)

Returning to the next words in Mojave Ghost, repeating three lines as well as the italicized question:

To reach for a world

that is out of reach.

What seest thou else in the dark backward?

Though no one calls, I look back again.

Which is when. Which is when I see you.

Repetition. A slant rhyme linking Gander’s “when” to Wright’s “again” in a different poem where she offers a question and punctuates with a period:

how does the cat continue

to lick itself from toenail to tailhole.

And how does a body break

bread with the word when the word

has broken. Again. And. Again.

Poetry has always sought conversation and risked misinterpretation. It is often accused of metaphysics. And yet it continues tilting its ear to the Aeolian, lest it miss a shade or a form. But this porousness and permeability is what lures us listen to Gander’s speaker, and study each syllable for sibilance or sibyl:

Glancing up from the page to acknowledge

no one there. Which is only

one of your forms.

Your voice, a rapture of silence. Incessant

immanence.

I look away. I look

back. And all has changed.

Like a moth hitting the windshield.

A lit cigarette tossed from a car

bursting into sparks along the dark road.

I recall the human event

of you turning your face

toward me for the first time. How

many lives before I fail to see it so clearly?

There are times when, in our mind at least,

we must swim back upstream

to where the love originated.

That it might be what it was and is again.

In bed and out.

Because all that is in me is in your eyes.

You, who are the discharge of my singularity.

I kept looking for better words to describe the infinitely-immediate music of Mojave Ghost. So I carried it on a trip to Rhode Island and let it meet snow. And I read the lines below aloud as the airplane rattled through crosswinds. And I copied them onto a postcard.

Tonight, I give up and elect to admire what it invests in the language of poetry. And so I close with an excerpt from one of Wright’s poems followed by a few lines from page 31 of Gander’s Ghost and leave the two to continue their dialogue:

WRIGHT

Believe me I am not being modest when I

admit my life doesn’t bear repeating. I

agreed to be the poet of one life,

one death alone. I have seen myself

in the black car. I have seen the retreat

of the black car.

GANDER

Narrative, you say, is just one way of navigating time.

And those perceptions culled

by the restraints of narrative

become available to other trajectories.

Meanwhile, the future blows toward us without handholds.

It is a gaping. An already. A maw.

What happens when the mind is no longer a place of duration?

If you want to resuscitate your destiny, you joked

early in our relationship, start with the present. Which

is when, for the first time, I took in the resolute

openness of your face.

*

C. D. Wright, “Against the Encroaching Grays” (Poetry Daily)

— “Alla Breve Loving”

— “Approximately Forever” (as shared by Matthew Leger)

— Cooling Time: An American Poetry Vigil (Copper Canyon Press)

— “Everyone in their car needs love…”

— “Everything Good between Men and Women” (Divas of Verse)

— “Flame”

— “Floating Trees”

— “Hotels”

— “In A Word, A World”

— “Jean Valentine, Abridged”

— “Lake Echo, Dear” (Read A Little Poetry)

— “My Dear Conflicted Reader…”

— “Obscurity and Selfhood”

— “only the crossing counts” (Divas of Verse)

— “Our Dust” (Divas of Verse)

— “Poem in Which Every Other Line is a Falsehood”

— “Scratch Music”

— “The Night Before the Sentence Is Carried Out”

— “The Secret Life of Musical Instruments”

— “This Couple”

— “What Keeps” (Poetry Daily)

Forrest Gander, Mojave Ghost (New Directions)

Jennifer Sperry Steinorth, “Relative Poetics: On C.D. Wright, Appropriation, and the Decentered Self” (Post 45)

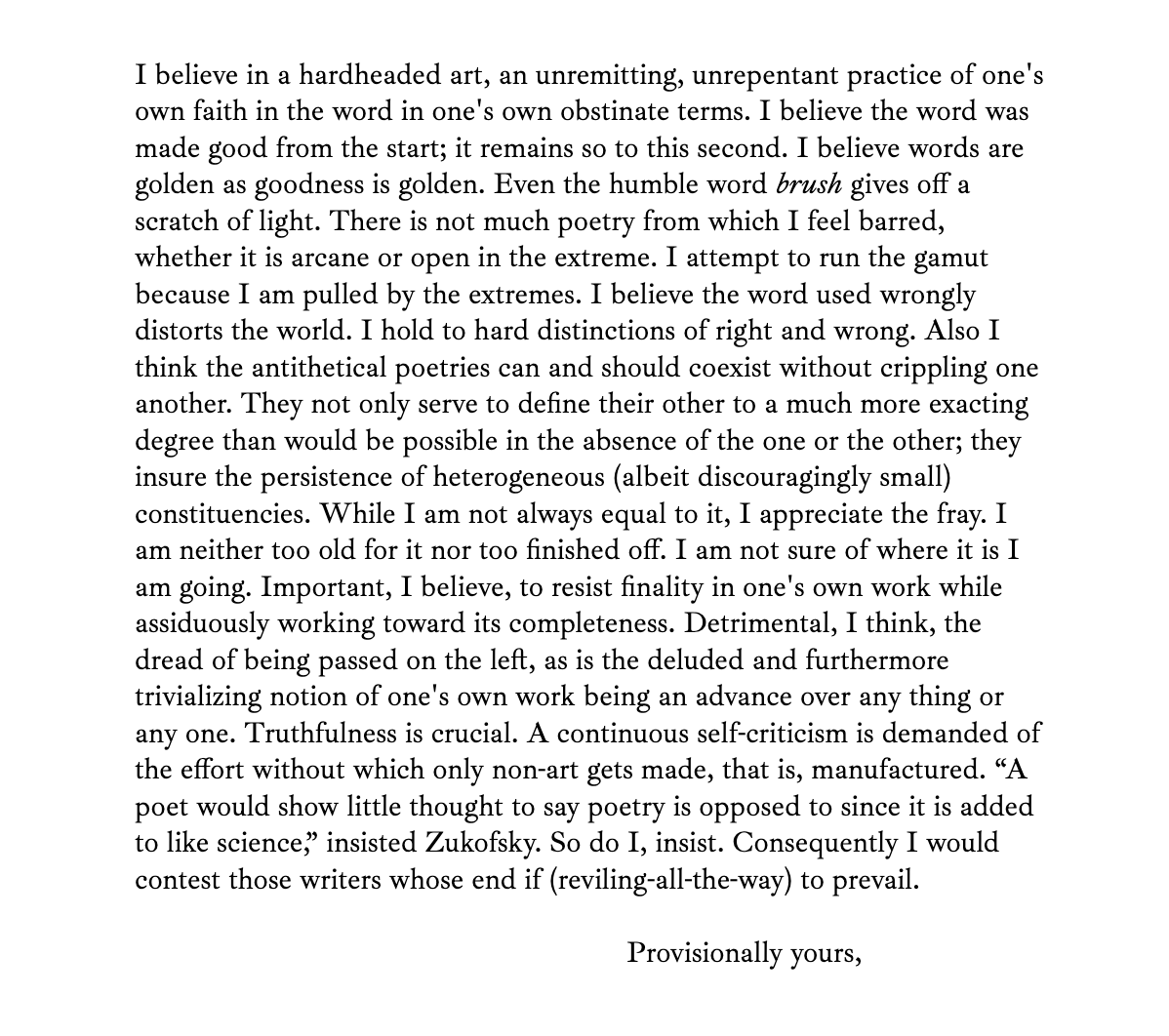

C. D. Wright, excerpted from Cooling Time: An American Poetry Vigil