“The moment of writing is not an escape, however; it is only an insistence, through the imagination, upon human ecstasy, and a reminder that such ecstasy remains as much a birthright in this world as misery remains a condition of it.”

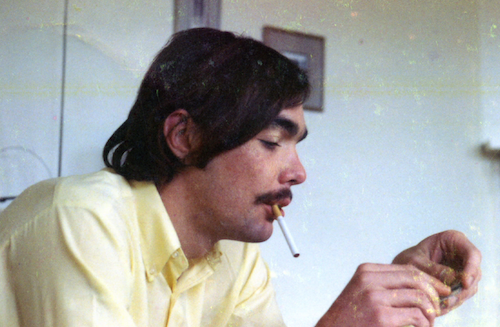

At one point in March 2024, I copied these words into a yellow notebook. It was the spring of Larry Levis; azaleas aching to bud, stammering possible colors in the margins of former journals. I remember thinking spring would destroy me, as it does annually, gutting me with its flushes and fevers, distracting me from the needs of surrounding mammals. Each day lengthening by inches of light. Moths moving like nocturnes near the doors. And Levis’ poems garlanding the floor of the porch with their gentleness…

WOUND

I’ve loved you

as a man loves an old wound

picked up in a razor fight

on a street nobody remembers.

Look at him:

even in the dark he touches it gently.

Like the ravish of spring, Levis seasons his stanzas with unremitting tenderness for life, the sap-work of being. I return often to his “My Story in a Late Style of Fire,” for the momentum it accrues as it winds down the page, working the space between the biography and the apologia:

I also had laughter, the affliction of angels & children.

Which can set a whole house on fire if you’d let it. And even then

You might still laugh to see all of your belongings set you free

In one long choiring of flames that sang only to you—

Either because no one else could hear them, or because

No one else wanted to. And, mostly, because they know.

… and for the inflammatory, unforgettable scherzo:

One of the flames, rising up in the scherzo of fire, turned

All the windows blank with light, & if that flame could speak,

… and for how Levis circles the figure of Billie Holiday, a talismanic figure that animated his jazz pantheon, jazz being the musical form that Levis deployed and studied for its repetitions and returns and metaphysical resonances.

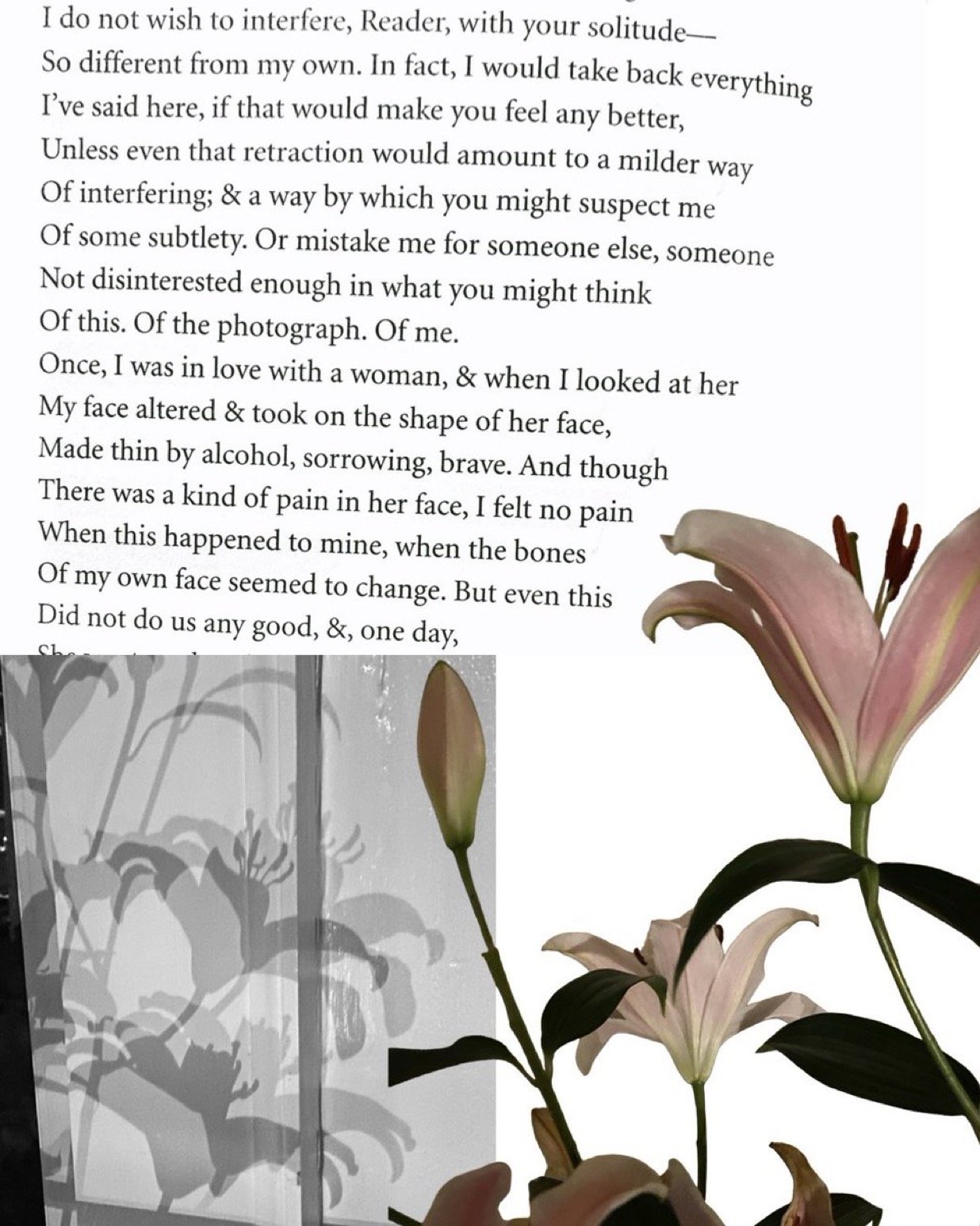

“My Story in a Late Style of Fire” is a self-portrait that leaps from the canvas like the face in Caravaggio’s convex shield, occupying the continuous present of poetic address. Yet its speaker takes leave of the reader with an embrace, a likening as bright as it is critical:

I know this isn’t much. But I wanted to explain this life to you, even if

I had to become, over the years, someone else to do it.

You have to think of me what you think of me. I had

To live my life, even its late, florid style. Before

You judge this, think of her. Then think of fire,

Its laughter, the music of splintering beams & glass,

The flames reaching through the second story of a house

Almost as if to—mistakenly—rescue someone who

Left you years ago. It is so American, fire. So like us.

Its desolation. And its eventual, brief triumph.

Brief, it is. Brief as the blooming set to a season. And what literary form turns this brevity to face vastness? Poetry.

Early in life, the gazer within commits the hand to grapple with traces. Poetry is the space he commits to inhabit, as Levis explains in “Autobiography”:

. . . when I was sixteen, I decided one night, to try to write a poem. When I was finished I turned out the light. I told myself that if the poem had one good line in it I would try to be a poet. And then I thought, no, you can't say “try.” You will either be a poet, and become a better and better one, or you will not be a poet. The next morning I woke and looked at what I'd written. It was awful. I knew it was awful. But it had one good line. One. All the important decisions in my life were made in that moment.

“One.”

Either you will or you won’t.

The once-upon-a-teen in me recognized a trajectory upon reading “The Poet At Seventeen”. The poem’s speaker dallies across an originary landscape without seeking to establish an origin in the calligraphy of resonance between the touch left on the billiards and “The trees, wearing their mysterious yellow sullenness / Like party dresses. And parties I didn’t attend.”

Levis narrows in on the significance of fingerprints in another poem, allowing an image to do the work of touching. I’m thinking of how a prefigurative “later” can be sweetened by the stone-scented dolor that straddles the span of his enjambments in “Those Graves in Rome”. The speaker imagines a fingerprint on a hotel barrister linking up with the name of a child who died of malaria long long ago in Rome in this speculative act known as metaphor:

weathered stone still wears

His name—not the way a girl might wear

The too large, faded blue workshirt of

A lover as she walks thoughtfully through

The Via Fratelli to buy bread, shrimp,

And wine for the evening meal with candles &

The laughter of her friends, & later the sweet

Enkindling of desire; but something else, something

Cut simply in stone by hand & meant to last

Because of the way a name, any name,

Is empty. And not empty. And almost enough.

Like that promise to save the poem in the name of one good line, Levis committed his words to their shadows, articulated by life’s tremulous conjunctions, its hesitations, its inconclusive hopes sparkling through the nearly’s and almost’s — “Is empty. And not empty. And almost enough.”

Maybe the presence of Levis’ younger selves is what lends his poems that particular texture of innocence (for lack of a better word) I associate with his speakers? Not blamelessness. Not purity. Something closer to motion, as in this splendid sentence from “Adolescence”:

And if death is an adolescent, closing his eyes to the music

On the radio of that passing car,

I think he does not know his own strength.

And what does the poet know?

How does he know it?

Contra the linear epics of empire, Levis eschews grandiosity for a tone and texture that subverts of the military decorum of officialdom. If he reminds me of the love-driven heresies committed to text by the Roman erotic elegists, it is because he lingers there, in the otium of elegiac, as with “Elegy for Whatever Had a Pattern in It”:

There is a blueprint of something never finished, something I'll never

Find my way out of, some web where the light rocks, back & forth,

Holding me in a time that's gone, bee at the windowsill & the cold

Coming back as it has to, tapping at the glass.

… or “Elegy with a Bridle in Its Hand”. (I should add that Tom Andrews wrote an unforgettable Wittgensteinian essay in dialogue with Levis’ elegies titled “The World As L. Found It”.)

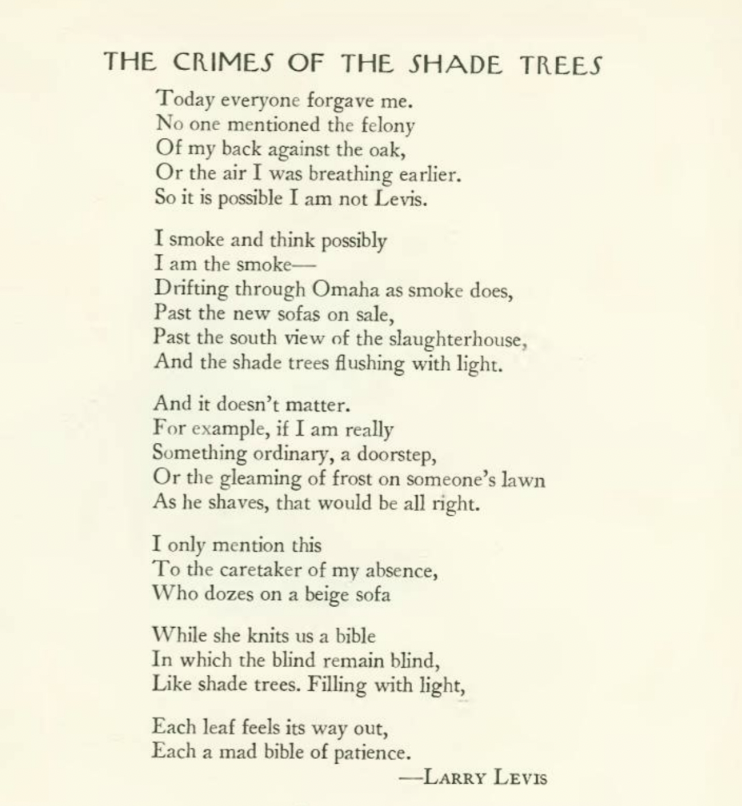

None has been so brazenly “wrong” as Levis in his poems — or so earnest in declaring it. One glimpses his “back against the oak” in “The Crimes of the Shade Trees” . . .

One meets them in the lowercase of “bible” demoted to improper noun, as well the wrangle of a difficult relationship with his father, as given in “Winter Stars”:

And for years I believed

That what went unsaid between us became empty,

And pure, like starlight, & that it persisted.

I got it all wrong.

I wound up believing in words the way a scientist

Believes in carbon, after death.

Literalism was lost on Levis. As was the fine art of disavowal. He holds his faults as close as his virtues in the self-portrait. There is an urge to Ars in Levis’ texts that calls to to mind something Terence Hayes once said in an early interview:

“Shaft and the Enchanted Shoe Factory” asks what kind of language (the shoes are a metaphor for language) should one wear into the world and do battle. That is part of what I'm interested in as a poet: how language can be worn and changed. Which is to say, I have very little interest in establishing a fixed style or subject matter. The Shaft poem is an ars poetica because it reflects my own quest for language. I'm very interested in wearing Larry Levis on one foot and Harryette Mullen on the other. Or on another day—in another poem- Gwendolyn Brooks and Frank O'Hara. Perhaps this quest is part of being a young poet. I hope not. I'd like to think I'd never be comfortable wearing the same shoes. Reading provides an infinite number of shoes and paths.

How to describe the surface tension of end-stopped lines like the one in “Map” — “At night I lie still like Bolivia.” — picking up the background noise and static electricity in the softer parts of the room?

Addressing the things that stir him, Levis turns the poem to face them, as with the “First Architect of the jungle & Author of pastel slums, / Patron Saint of rust” in “Twelve Thirty One Nineteen Ninety Nine” — and then layers rhetorical questions before orienting his eye to the small, nameless characters of the small town, calling them forward:

Goodbye, little century.

Goodbye, riderless black horse that trots

From one side of the street to the other,

Trying to find its way

Out of the parade.

The “riderless black horse” may have better answers than the conclusivity we crave. Levis burrows into these pockets where light is absented; he studies silhouettes and reflective surfaces; he garners luminescence from mirrors. The metaphysics of prom night bubbles up in “Toad, Hog, Assassin, Mirror”:

At the other end of the hedgerows someone attractive is laughing, either at them, or with a lover during sexual intercourse. So it is like prom night? Yes. But what is the end of prom night? The end of prom night is inside the rodent.

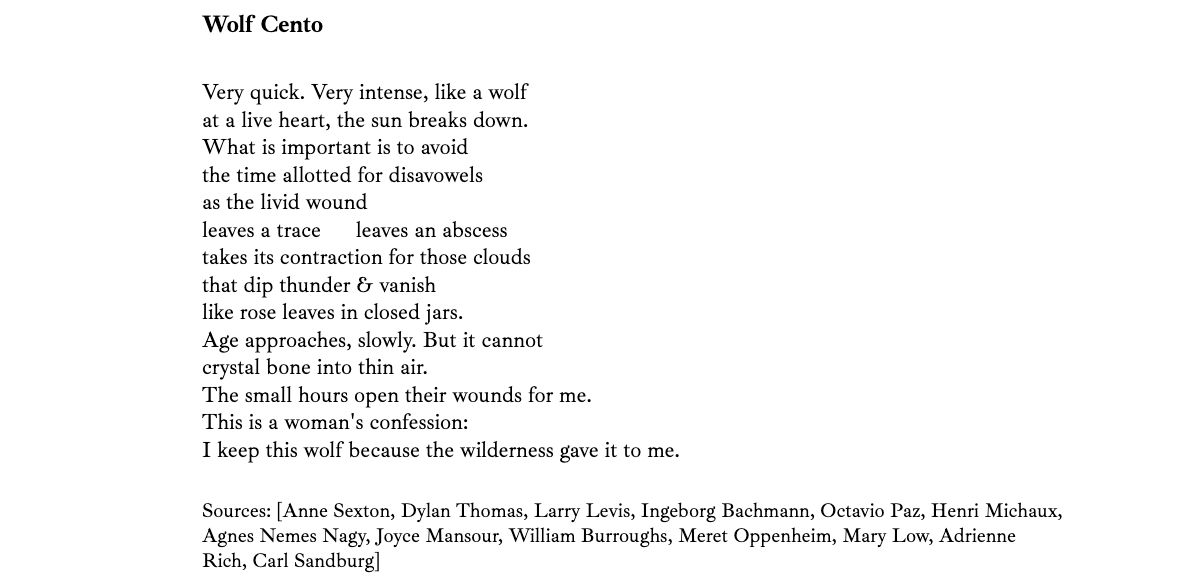

Lines from his poems appear in Nicole Sealey’s “Cento for the Night I Said 'I Love You’” as well as Simon Meunch’s “Wolf Cento” — which I offer in full below, out of sheer love for this ancient form:

[Aside: Notice how the use of a large space between words in the 6th line —- “leaves a trace leaves an abscess” — adds breath and visual interest to that particular line. Meunch’s “Wolf Cento” is a vestigial sonnet, and it maintains a relationship to that 14-line length, so that spacing might also be the result of a divided quotation, or the desire to not add an extra line between the two. Hewing close to the erstwhile sonnet asks Muench to refuse the line break. These are the compositional and structural choices involved in cento-making, particularly when one is playing with multiple forms simultaneously, as the poet does in this poem.]

*

Jacques J. Rancourt wrote a splendid tribute to Levis’ legacy, noting “a catechistic logic to Levis’s poems: memory, confession, penance” as well as the prevalence of “liturgical vocabulary: loss, testify, darkening, late, exile.” What caught my eye was Rancourt’s insight on Levis’ ampersand:

This shift toward the ampersand came at a pivotal moment in Levis’s career. While his first three books offer glimmers of the poet he’d become, it isn’t until Winter Stars—when the ampersand first appears—that his vision and style crystallize into the virtuoso work we know today. The ampersand embodies one of Levis’s signatures: yoking together two surprising ideas or dyads to complicate and expand each through their pairing. Take lines like “the missing & innumerable stars” from “Anastasia & Sandman,” or “having to imagine everything/In detail, & without end” from “Poem Ending with a Hotel on Fire,” or “My father died, & I was still in love” from “In the City of Light,” or “The morning will be bright, & wrong” from “Gossip in the Village.” But if we zoom out, this technique is also emblematic of how he fuses different recursive narrative threads, images, and motifs across his long poems and collections. Consider, for example, how the phrase “the sprawl of a wave,” a shape whose image mirrors the curling glyph of the ampersand itself, echoes across all of his later books. The ampersand, quicker than the coordinating conjunction, accelerates the pairing, blurring their edges until they deepen each other.

Rancourt expresses the beauty of Levis’ ampersand perfectly.

I made a note of it, and then took Radu for a walk on this night of the Chinese New Year.

Amid the shadows of alley cats dilated by street lamps, I mulled what prevents me from hearing Levis’ liturgical references as Catholic. Something about his fluency with negation feels closer to mysticism and the kenosis of Simone Weil, threads of the sacred that hover at the rim of the heretical. Formally, Levis gravitated across poetic forms and lineation strategies; his range includes a poem composed entirely of tercets (like “A Study of Three Crows”) as well as the long lines of his lengthier pieces. He can’t be easily classed as part of a particular school.

If one thing remains consistent across his writing, it is Levis’ unrelenting attention to light —- to light and shadow, the eye transfixed by chiaroscuro. I can’t find a poem that misses this shading, and it often determines the perspectival decisions in his ekphrastic poems like “Edward Hopper, Hotel Room, 1931”:

You think of curves, of the slow, mild arcs

Of harbors in California: Half Moon Bay,

Malibu, names that seem to undress

When you say them, beaches that stay white

Until you get there. Still, you’re only thirty-five,

And that is not too old to be a single woman,

Traveling west with a purse in her gray lap

Until all of Kansas dies inside her stare...

Edward Hopper, Hotel Room (1931)

Edward Hopper painted countless unpeopled landscapes, but when a poet wants to talk about loneliness, they usually refer to one of Hopper's paintings of humans in a room or a diner. Unlike the field or the mountain, a room is a space created by humans to protect and nurture what is human. Rooms imply safety, security, relationality— but Hopper's rooms give us humans inches away from each other, incapable of connecting.

Light touches both.

Light, or the way light is depicted, can connect figures and subjects in art. Light enters a room through windows, doors, crevices, etc.; it speaks at a distance by creating its own characters, namely, shadows.

The shadow is a being created entirely by light.

Between dusk and sunset, the golden hour descends, running its gilded hands over skin, burnishing human eyes and hair, as if to warm them from the inside before leaving them to vanish in darkness.

Sunlight covers the constructed human environments as well as the given, natural ones. In his early years, Hopper believed that sunlight was a hue of white rather than yellow.

“Utter whiteness is scary: it can be erotic in an incredible way, and one which seems contradictory— eros and terror," Larry Levis said in an interview with David Wojahn. And "nobody knows how to make light work on skin in its utter whiteness the way Hopper does," he added. Levis suspected Hopper "wanted to paint sunlight on the side of walls" more than he wanted to paint characters or people.

Oil and charcoal on cotton duck— the materials Richard Diebenkorn used to create Ocean Park #17 (1968) — convene in the textures and surfaces of Levis’ “Ocean Park #17, 1968: Homage to Diebenkorn”.

Again, light meets Levis’ yellows in interstitial space of remembrance:

And the inextricable candor of doubt by which Diebenkorn,

One afternoon, made his presence known

In the yellow pastels, then wiped his knuckles with a rag —

Are one — are the salt, the nowhere & the cold —

The entwined limbs of lovers & the cold wave’s sprawl.

Unlit, this presence of “no one” in “Unfinished Poem” . . .

Here are all the shadows that have fallen on

no one in particular

The starkness of the immediate in “La Strada”. . .

This life & no other. The flesh so innocent it walks along

The road, believing it, & ceases to be ours.

The way light reverberates through the rooms of Levis’ life like the gold leaf of illuminated manuscripts, hallowing particular moments and bringing them into the sharp relief, as with the final stanzas of “The City of Light”:

A body wishes to be held, & held, & what

Can you do about that?

Because there are faces I might never see again,

There are two things I want to remember

About light, & what it does to us.

Her bright, green eyes at an airport— how they widened

As if in disbelief;

And my father opening the gate: a lit, & silent

City.

The promise and premise of brightness across multiple poems . . .

GOSSIP IN THE VILLAGE

I told no one, but the snows came, anyway.

They weren't even serious about it, at first.

Then, they seemed to say, if nothing happened,

Snow could say that, & almost perfectly.

The village slept in the gunmetal of its evening.

And there, through a thin dress once, I touched

A body so alive & eager I thought it must be

Someone else's soul. And though I was mistaken,

And though we parted, & the roads kept thawing between snows

In the first spring sun, & it was all, like spring,

Irrevocable, irony has made me thinner. Someday, weeks

From now, I will wake alone. My fate, I will think,

Will be to have no fate. I will feel suddenly hungry.

The morning will be bright, & wrong.

The constant attention to lighting, as if light itself could forge the line break in poems “A Letter”:

And the emptiness of dusk. Someone put it

Crudely: to fuck is to know. If that is true,

There’s a corollary: the soul is a canary sent Into the mines.

There is a Latin phrase commonly used on ancient graves (shortened as STTL) which catches the light that emanates from Larry Levis— it is a different form of light, a lightness that doesn’t resolve in transcendence.

Sit tibi terra levis — or, May the earth be light to you, Larry Levis. May the immanence of your lights continue speaking as lyric.

*

Billie Holiday, “Good Morning Heartache”

Billie’s Best, the Verve album released in 1992 that played as I watched the first sunrise of 1993

Edward Byrne, “The Life and Legacy of Larry Levis” (Valparaiso Poetry Review)

Edward Hopper, Hotel Room, 1931

Elissa Gabbert on Levis’ Swirl Vortex (New York Times)

Jacques J. Rancourt, “Destroying Time: On the Lasting Legacy of Larry Levis” (Poetry)

Larry Levis, Swirl & Vortex: Collected Poems edited by David St. John (Graywolf Press)

Larry Levis, excerpts from “Some Notes on the Gazer Within” (PDF)

Larry Levis, “My Story in a Late Style of Fire” (PDF)

Larry Levis, “Elegy for Whatever Had a Pattern in It” (PDF)

Larry Levis, “In the City of Light” (PDF)

Larry Levis, “Winter Stars” (PDF)

Larry Levis, “Linnets” (Blackbird)

Larry Levis, “Readings in French” (courtesy of Maureen Thorson)

Larry Levis, “Edward Hopper, Hotel Room, 1931”

Michael Thomsen, “Anatomy of a Deathwish” (Berfrois)

Norman Dubie, “A Genesis Text for Larry Levis, Who Died Alone” (Nashville Review)

Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park #17, 1968 (Stanley Museum of Art)

Shara Lessly, “Beautiful, Hopeless, and Wrong” (Adroit Journal)

Talia Marshall, “This Is the Way He Walked Into the Darkest, Pinkest Part of the Whale and Cried Don’t Tell the Others” (Poetry)

Terence Hayes and Charles Henry Rowell, “‘The Poet in the Enchanted Shoe Factory’: An Interview with Terrance Hayes” (Callaloo)

Tom Andrews, “The World As L. Found It” (Blackbird)