for Jared, who said that words have not visited him in a month — in the hopes that they do so, soon

Francesca Woodman was born on April 3rd, 1958. At the age of thirteen, she began taking photographs of herself, a practice she continued until her death. Looking at Woodman’s photos can be jarring— not so much due to the nudity but because we tend to overhear this dialogue between the girl and the woman defined by shifting embodiments. When a friend mentioned looking for ways into writing about Woodman’s work, my hope for his poetry led to this clumsy scaffold of circuits and alleys into ekphrastic poems.

“I have said many, many times no place is home.”

— Robert Hayden, as quoted by Reginald Dwayne Betts in “Remembering Hayden”

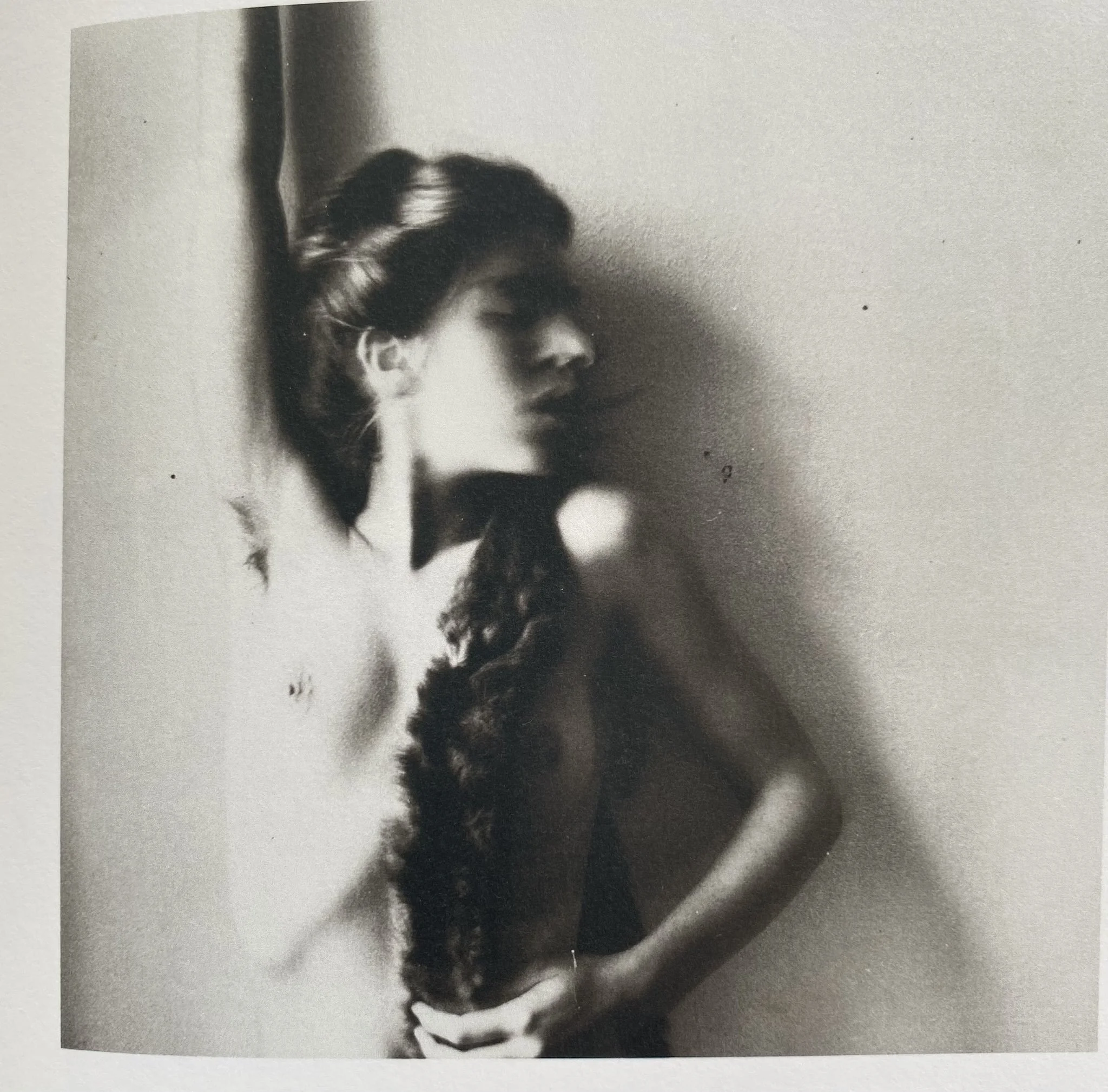

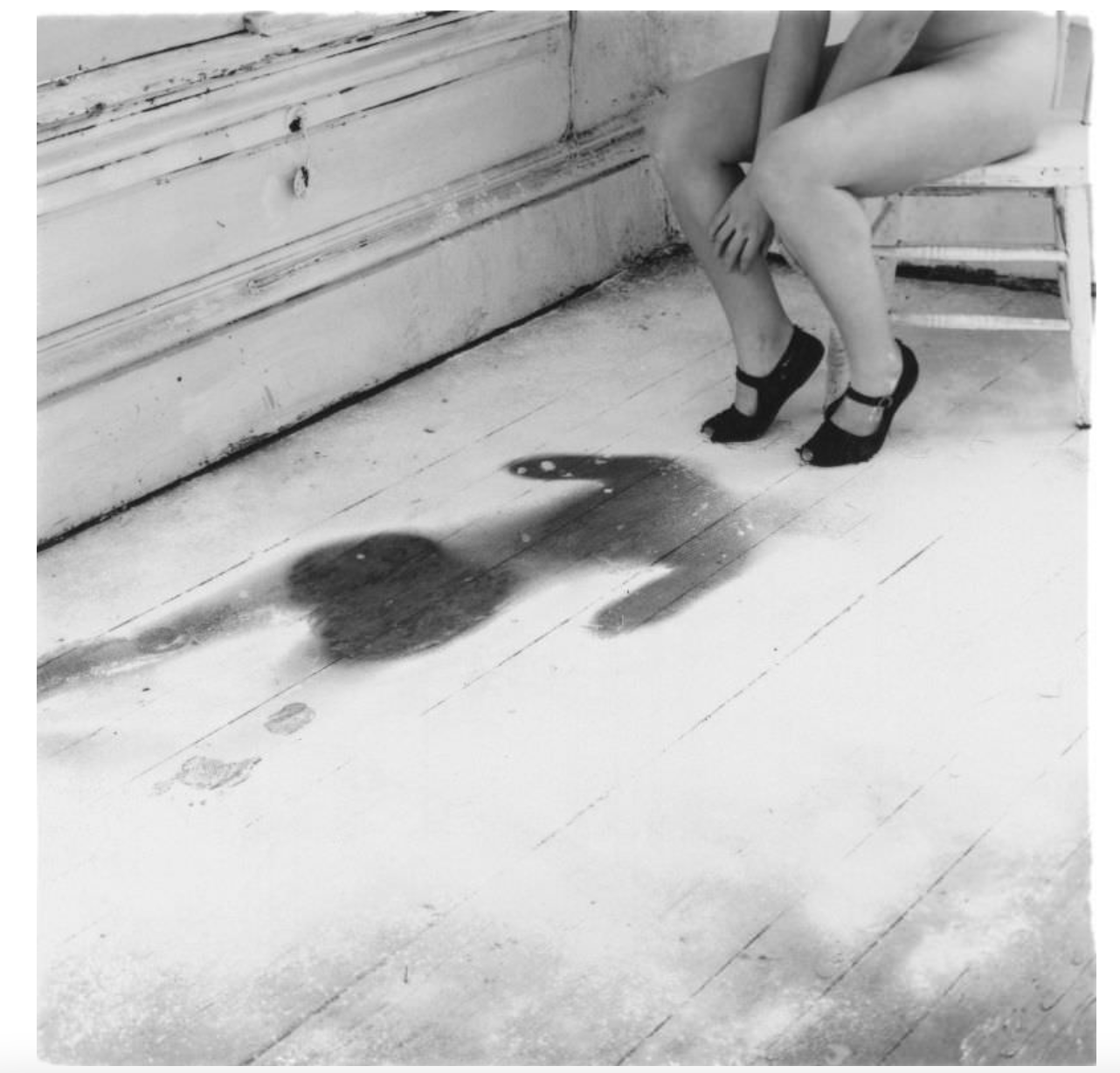

1 ] from Untitled (MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, New Hampshire), 1980

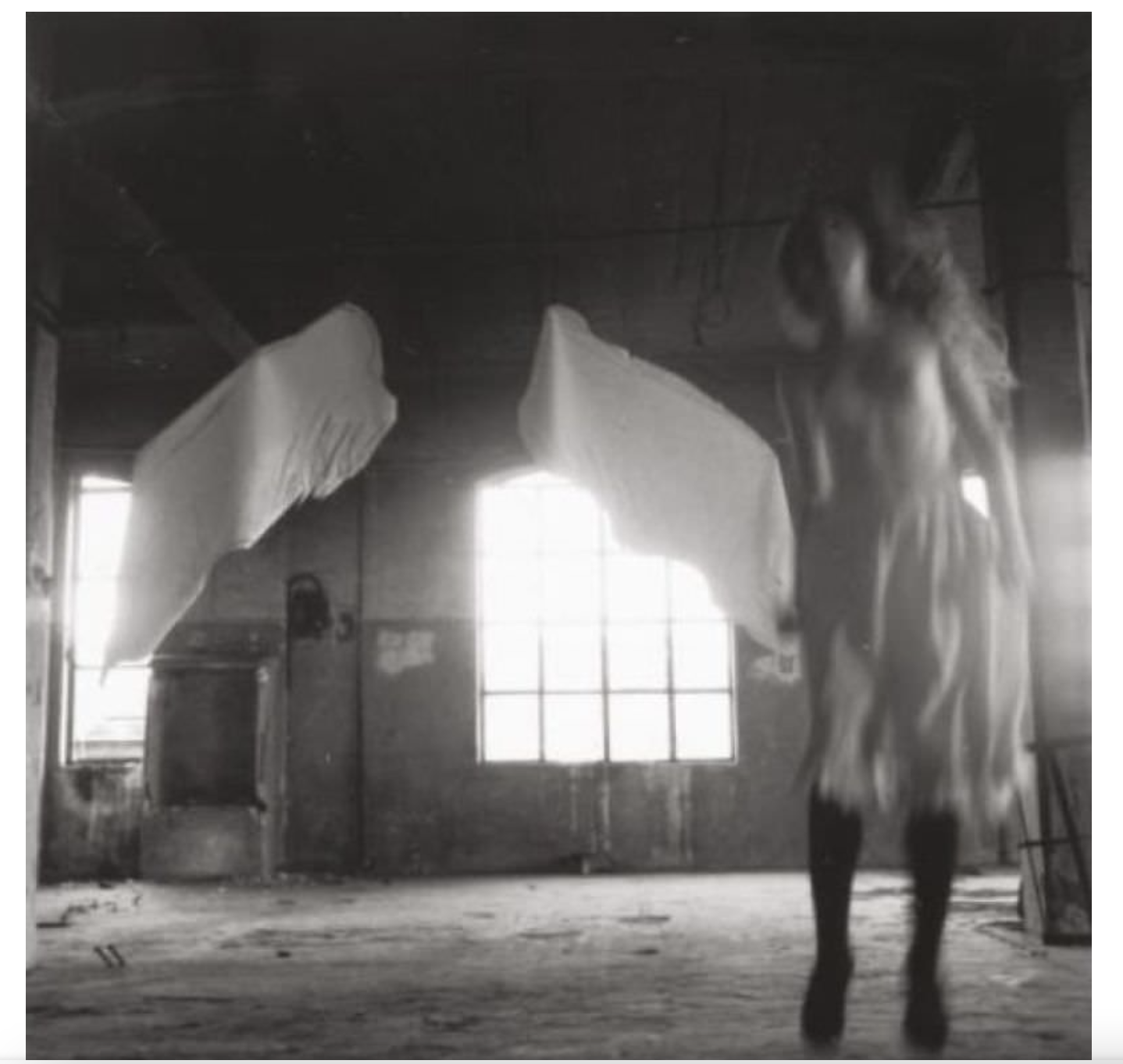

Photographs have time-stamps: they are taken in one shot rather than an extended sitting (as with oil paintings). The photographic medium assumes that the camera fixes time and space, but Woodman rejected this by mixing vintage clothing, ruined interiors, and angles of light that evoked a sense of decay. There is an already-ruined feel to her portraits, even the ones that feature motion.

One could write a poem about time, or an ekphrasis that considers temporal notations. In so doing, one might consider the following questions: What part of the figure is still moving? What archaic object seems pulled out of time? How does the word “heirloom” break across this image, beginning with the hairstyle and ending with the mink stole? What does it mean to be pulled out of? And why does the shadow of the figure against the wall seem to imply an extended arm, or a part that keeps moving outwards from the elbow?

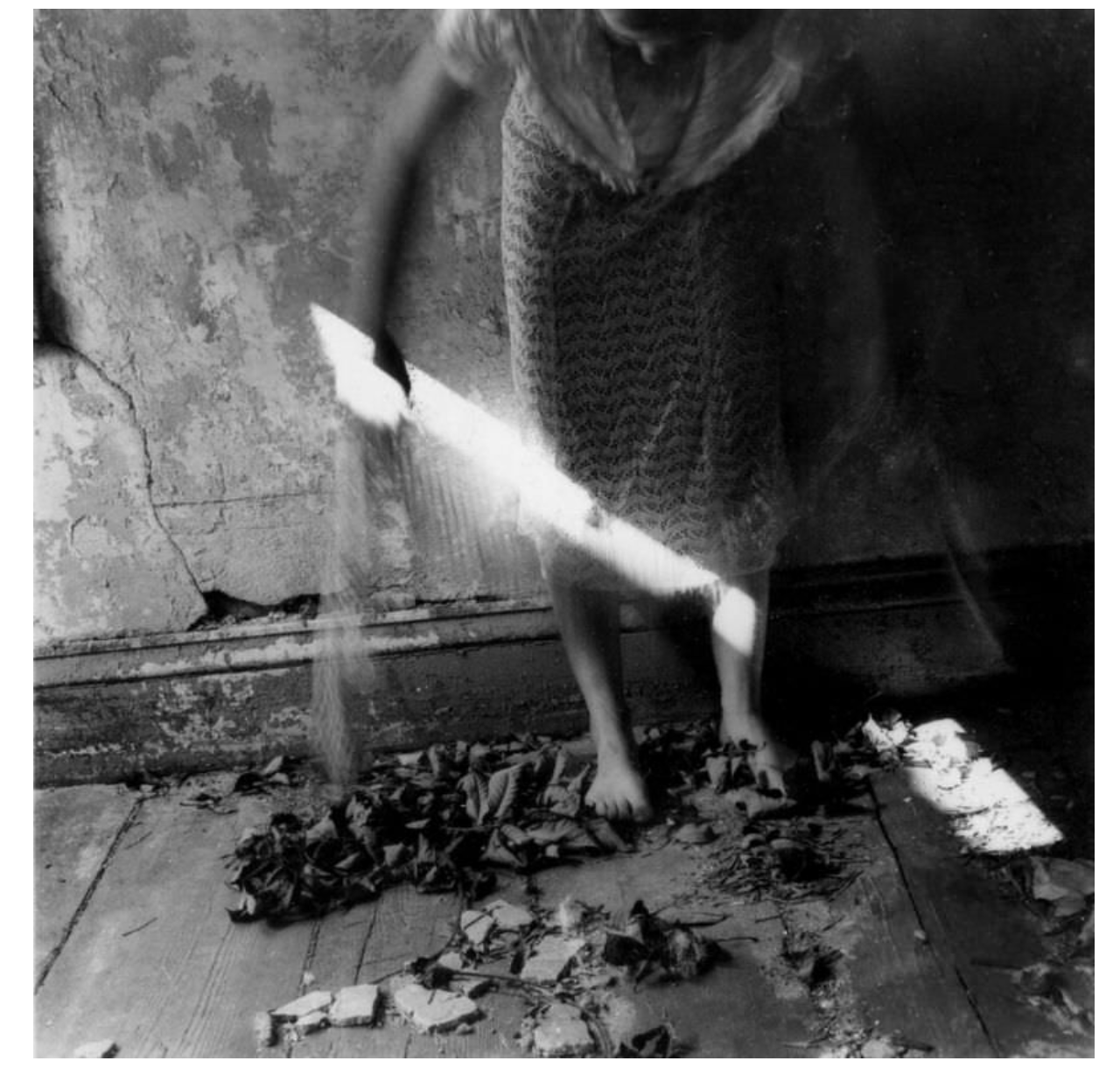

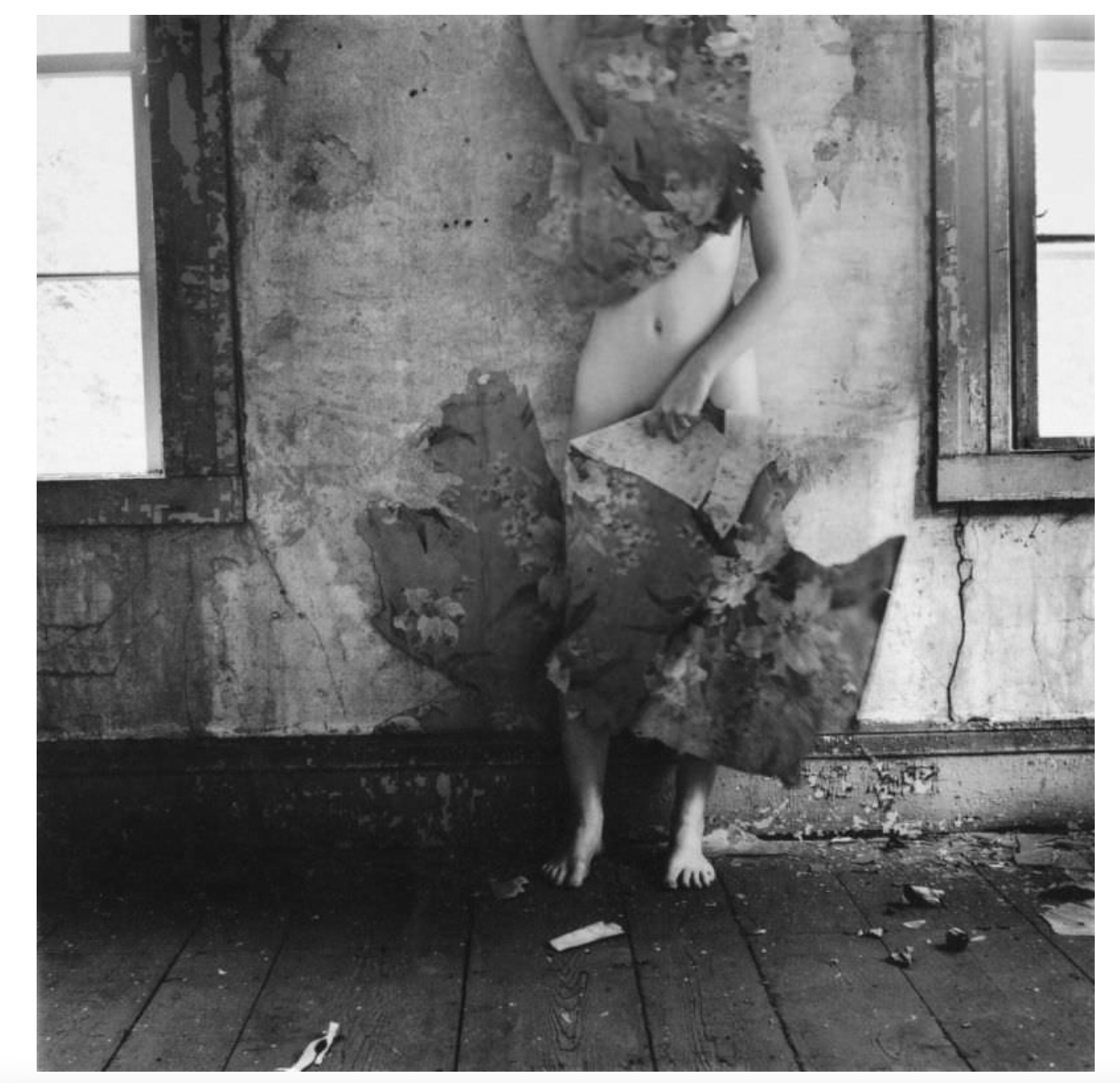

2 ] House # 3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976

“Sous la nuit” by Alexandra Piznarik

The night is the color of the eyelids of the dead.

I escape all night long. I orchestrate the chase, the fugue. I sing a song to my affliction. Black birds over black shrouds.

I scream in my mind. The demented wind denies me. I have confined myself. I draw back from the tense hand. I don't want to know anything except this clamor, this night panting, this errancy, this not finding.

All night long I make the night.

All night long you abandon me slowly like water falling slowly. All night long I write, to look for the one who looks for me.

Word by word I am writing the night.

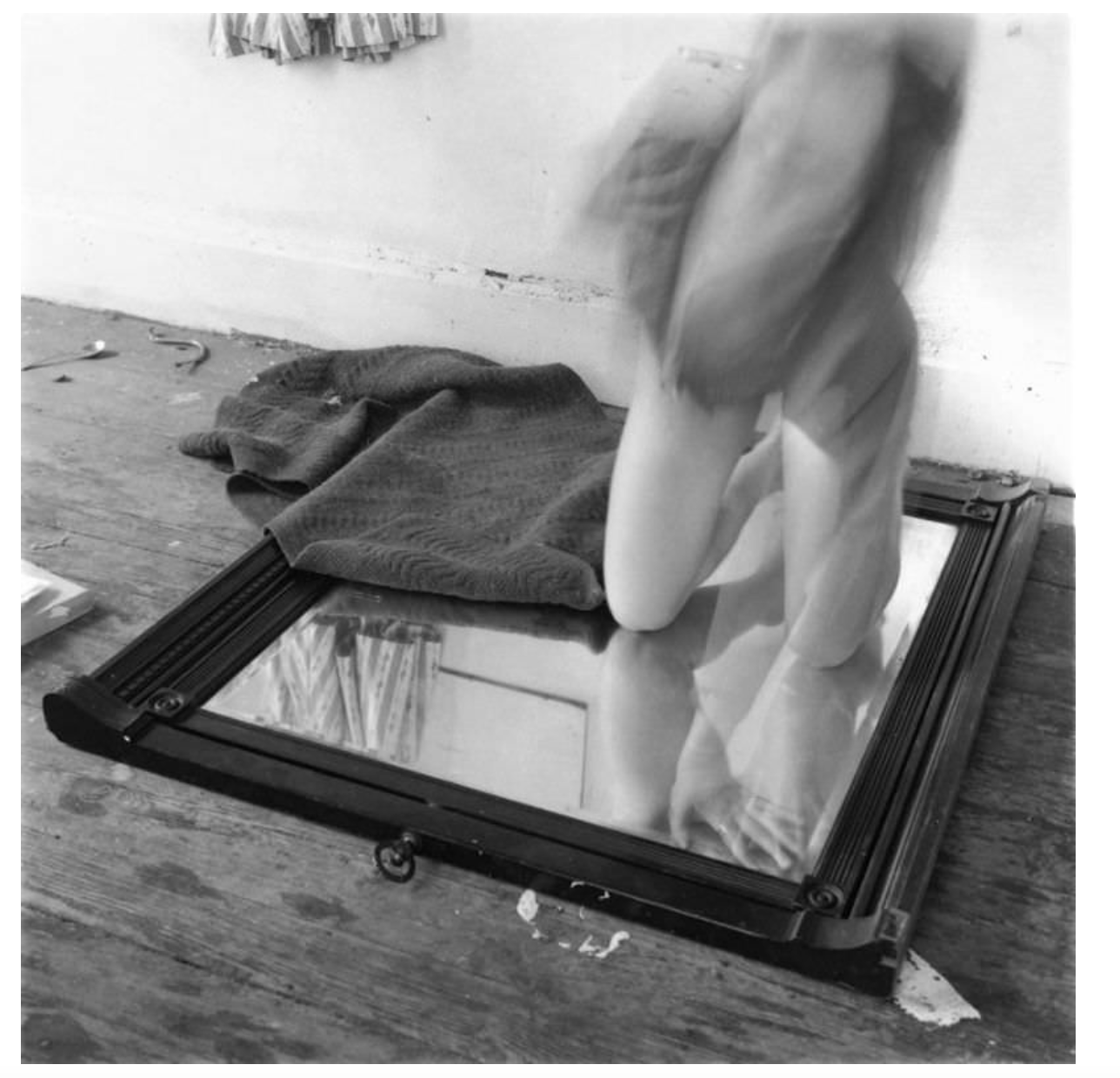

Piznarik dedicated this poem as follows: For Y. Yuán Pizarnik de Kolikovski, my father. If one wanted to play with juxtapositions and locutions between works of art, one could perhaps write a poem about Woodman’s “#5 House # 3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976” that begins and ends with one of the lines from Piznarik’s poem. . . . as in, I have confined myself. The paper peels off the wall near the window frame. Words scamper behind the hearth. The mantle, unglued. Your white shutters are solid, visible only from the exterior. But inside the house of my head, flowers take their last breath on the plaster. It is my arm that cannot stop moving. I write to look for the one who looks for me. (etc. etc)

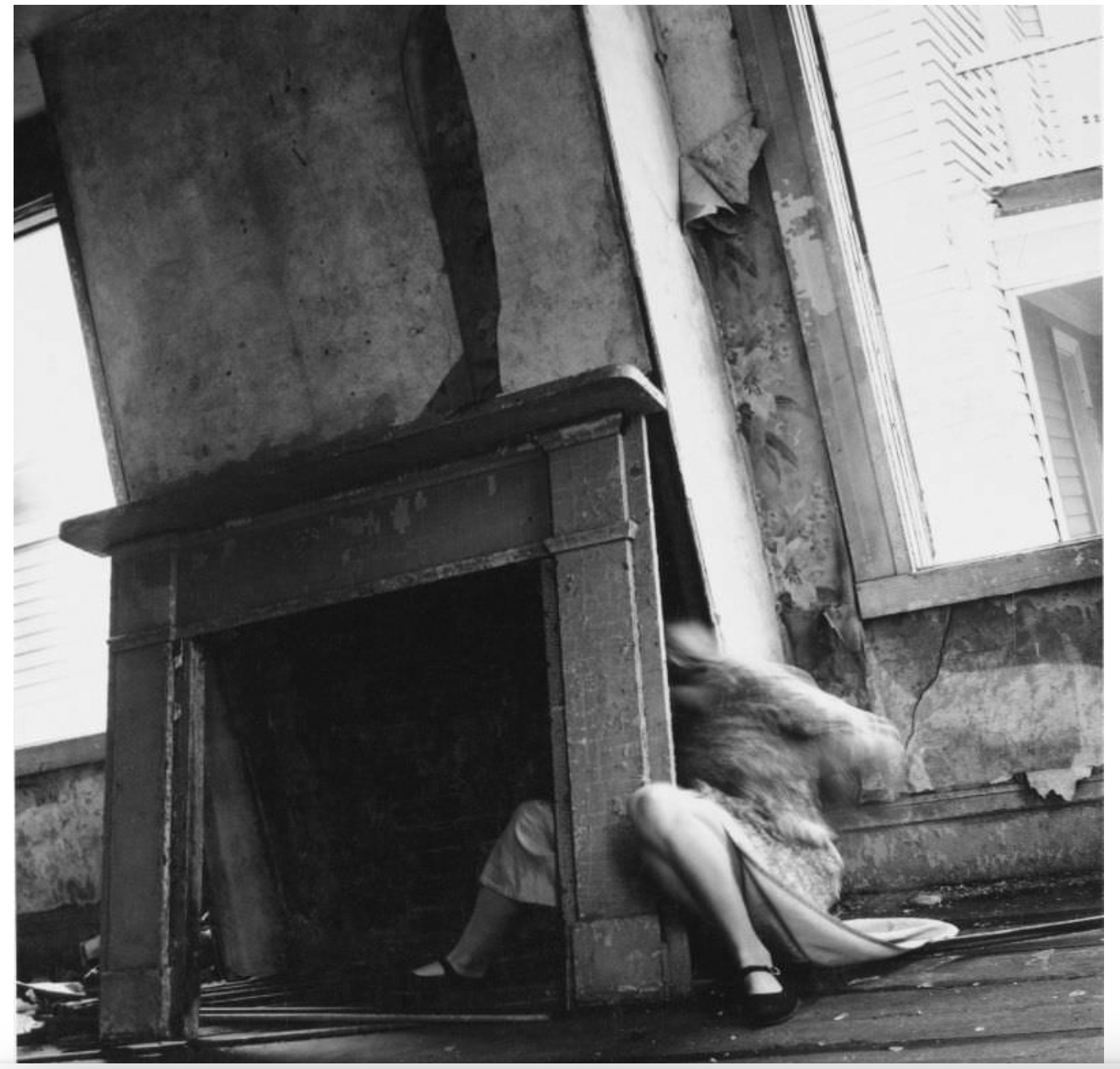

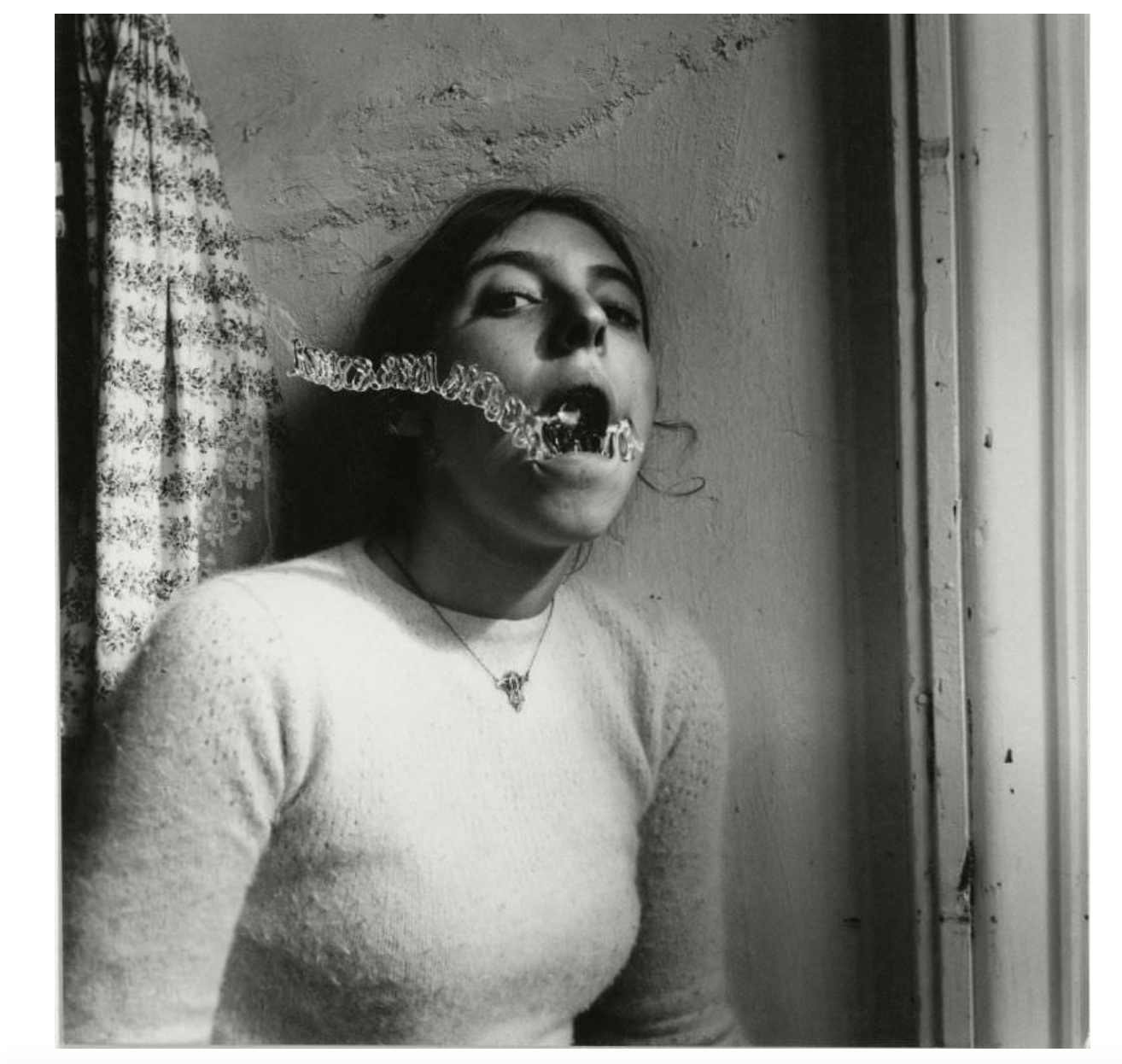

3] #16 from Angel Series, 1977

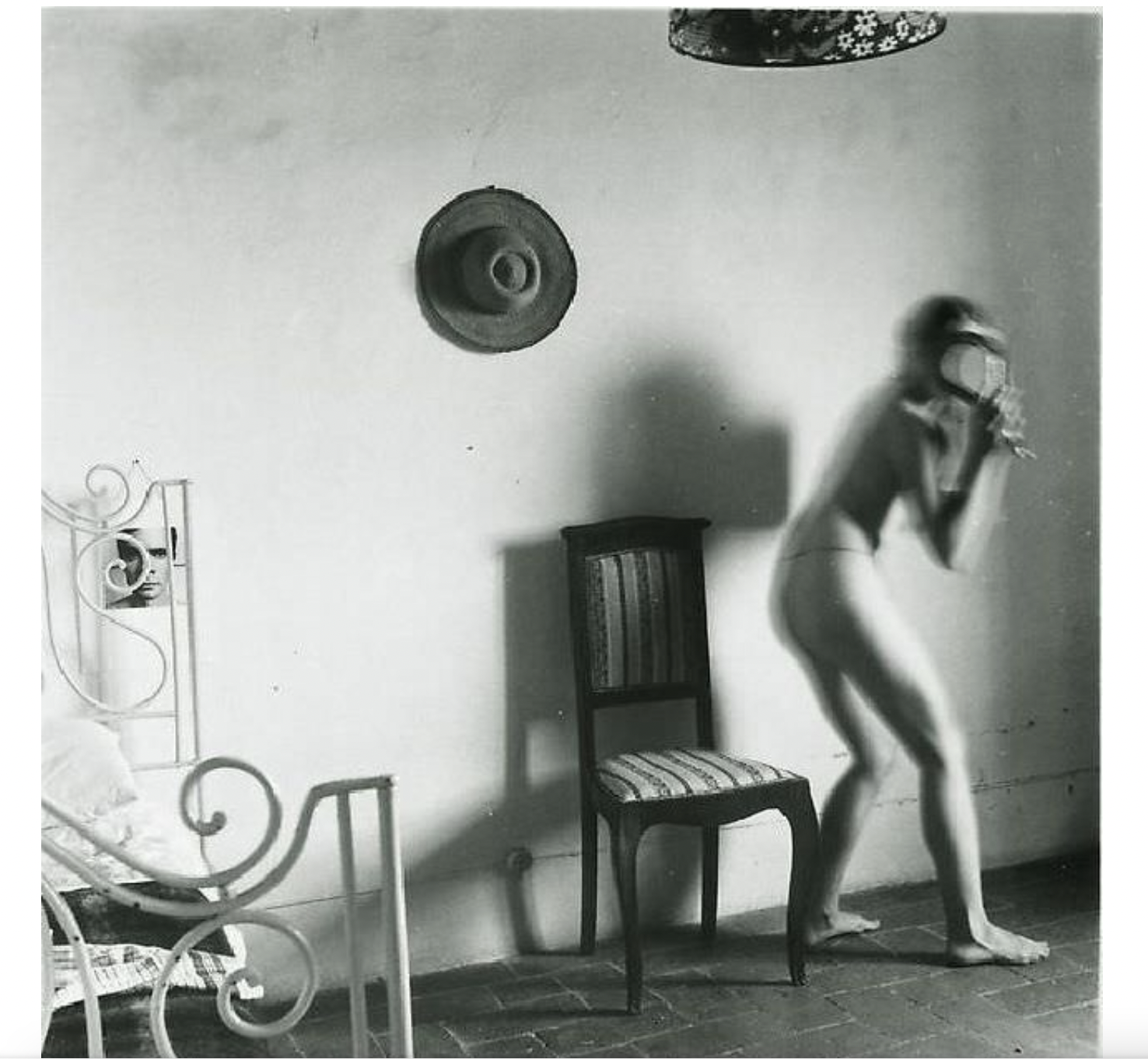

For Rainer Maria Rilke, the limits of the lament are always transcribed, and therefore limited by the medium of language. In June 1915, while struggling to draft a poem, Rilke proposed the kingdom of the dead as “a unique, fabulous existence” contra the insignificant brevity of the life we are given, or what he called this “anomaly”. . . Already, one can see the poet laying out his angels and demons among the audience to which he is beholden. “What weight, what obligation now falls on things that survive a little more…” Rilke muses. The heart is incapable of love, only of “passing things on” – “there is no one who can draw sounds from the air that sweeps through him, not even to lament, – it is a Silence of halted, interrupted hearts.”

To be fair, the angels visited him long before this date, and they appear in his letters. Setting Rilke’s words about angels next to this image from Woodman’s Angel Series, one could consider drafting an ekphrastic “lament” related to angels, or the angelic. Woodman complicates the concept of the “angelic” with the fly paper hanging from the ceiling, and the flypaper dripping from the figure’s fingertips. Dead flies punctuate the left flystrip: small black beads, dead bodies. A single-stanza lament (no longer than ten lines) for whatever you mourn in this. An added constraint: to use the Rilke’s words, “What weight, what obligation now falls on things that survive a little more…” as an epigraph or a question that the lament seeks to address.

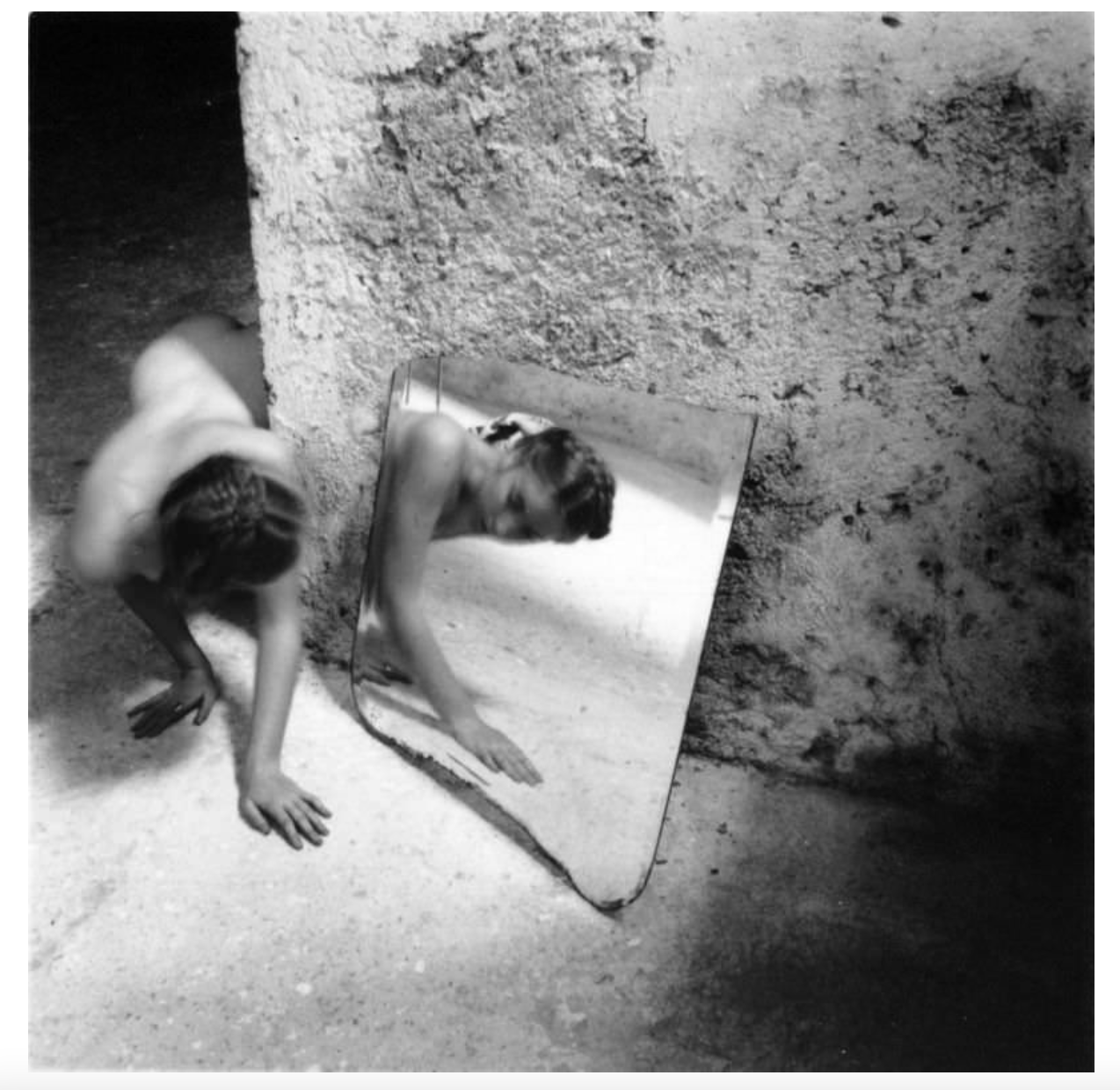

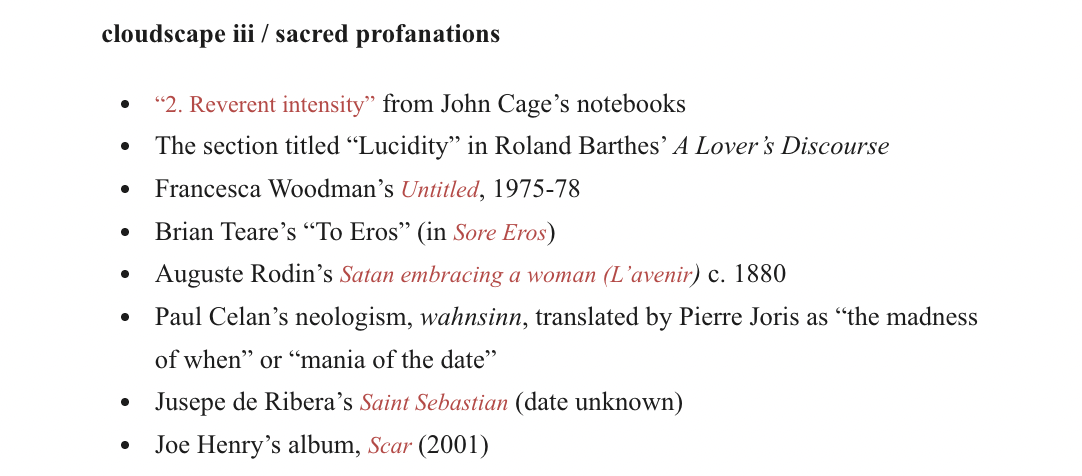

4] Self-Deceit # 1, Rome, 1977

In the year prior to this photograph, Francesca Woodman spent time in Providence working on a series that foregrounded hands. Her statement — “Then at one point I did not need to translate the notes; they went directly to my hands” — is often associated with those 1976 Providence photos, and used to title one of them. But “Self-Deceit # 1” from a series shot in Rome in 1977 doubles up on two of Woodman’s overt fascinations, namely the hands and the mirror, while also giving us the archaic bun, the perfectly poised hair above the naked body. The figure seems to be looking at her hands. She approaches the mirror on her knees, crawling around the corner, the contract between skin and rough concrete, hard and soft, impermeable and porous.

I keep returning to the hands— the left hand is ringless, the right hand bearing a silver ring on the forefinger— and the object above her nape that is reflected back from the mirror but invisible to us from our perspective. Since this photo touches me in very personal ways, I would be tempted to warm my way into it by playing with very tight constraints or structures. I might flex my muscles by, for example, making a brief inventory of nouns, adjectives, and verbs that this image elicits. Then I might listen to music while playing a game of Mad Libs with a section from an Anne Sexton poem:

And if you turn away

because there is a/no (noun) on the page,

I will (verb) my (adjective) bowl,

with all its (adjective) stars (adverb that modified ‘stars’)

like a (adjective) lie,

and (verb) a (adjective) (noun) around it

as if (person/pronoun) were (verb) (noun acted upon by prior verb)

or a strange (noun).

Not that it was (abstraction or proper noun that refers to a specific place),

but that I (past tense verb) some (abstraction) there.

Then I would take Radu for a walk and disorder the lines in the Mad Lib and see if any one of them gives me a beginning or creates a motion into the poem that would probably be titled “The First Self-Deceit.”

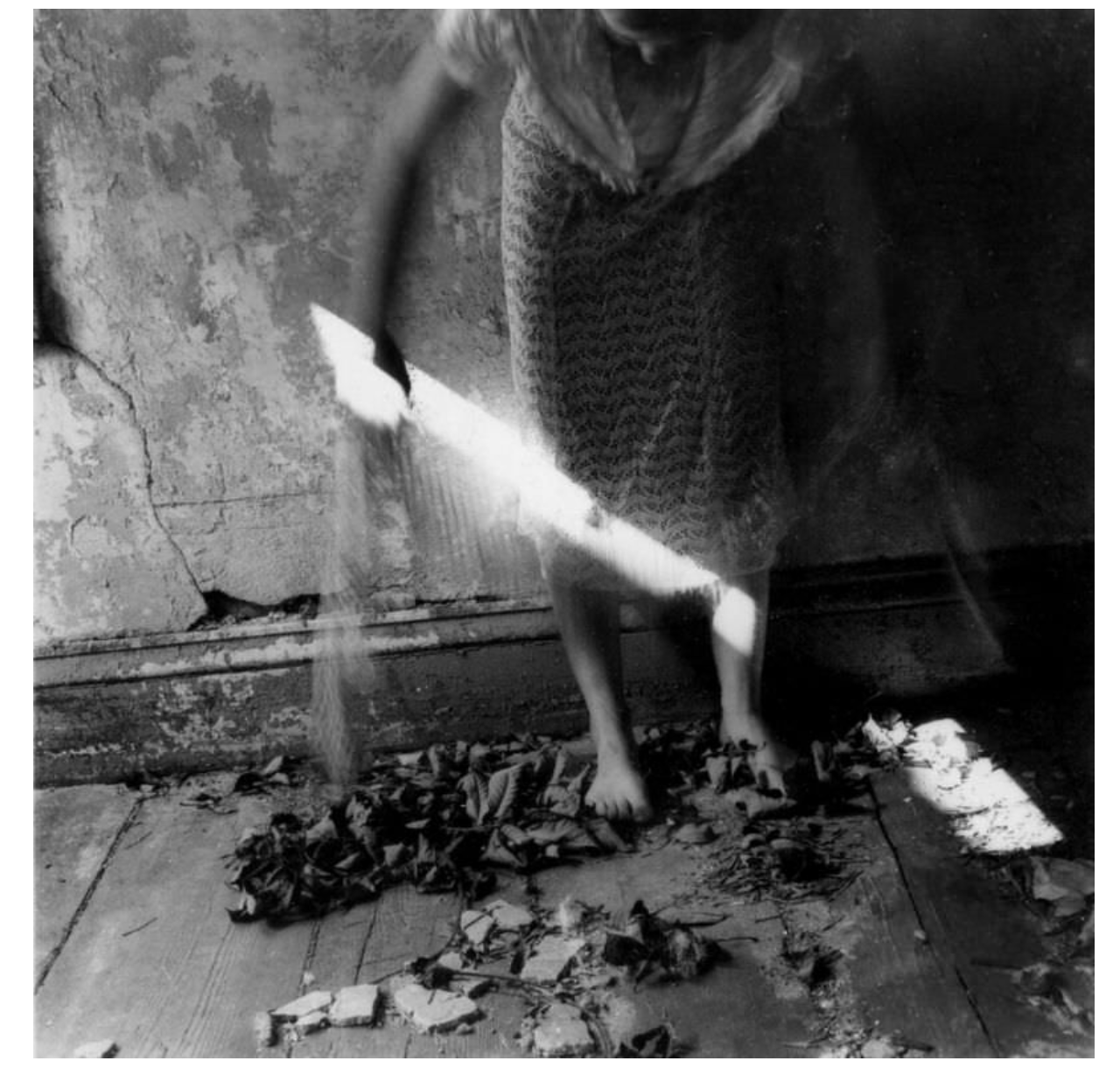

5] A slideshow of Woodman’s photos + a gesture of aposiopesis

Aposiopesis (derived from the Greek word that means “becoming silent”) is a rhetorical device that can be defined as a figure of speech in which the speaker or writer breaks off abruptly, and leaves the statement incomplete. It is as if the speaker is unwilling or incapable of stating what is present in her mind, due to being overcome by passion, excitement, or fear.

Aposiopesis leaves a statement unfinished, so that the reader can determine his own meanings. One could even say that aposiopesis unfinishes a statement, and draws the reader into a complicity with the poem, a labor of imagining and co-creating the unsaid. Pace silence, I suspect breaking-off can also occur with a repetition of syllables, which is to say: sometimes I hear aposiopesis as a stutter, an unsilence marked by an ellipsis . . . a rendering of sound as jagged and fragmented, unable to continue, caught in the repetition of syllables that cannot quite cohere into the wholeness of words. I leave you with a series of images by Woodman and the possibility of a poem structured by what it withholds through aposiopesis.

If you can’t get started or find an in-road into these images, I’m leaving a few questions/non-questions for you to consider when assembling images and textures for the room of the possible poem:

What falls like a leash from a hand without a glove.

Where all the words are a species of silk.

Why the sky hides a rind at the rim.

Who is yours.

What is not enough.

What is barely.

Whose lips are not ink eventually.

Why light fashions us accidentally.

What does your midnight find necessary.

POSTLUDE

Woodman’s Blueprint for a Temple II, 1980 influenced several poems in My Heresies, particularly in the deconstructions of profanation and use of light. The same could be said of the details and tensions juxtaposed in the objects below, which I reference just in case they are generative for others.