“Aussi peu de temps et nous avons marché sous la pluie

Je parlais d'amour et toi tu parlais de ton pays”

— Nino Ferrer, “La rua Madureira”

“Life is real

And the days burn off like leopard print

Nobody, not even the dead can tell me what to do”

— Hera Lindsay Bird, “Keats Is Dead So Fuck Me From Behind”

1

Today: work day. The shafts of burnt Estérel pines came back to me strongly, I tried to make something of it, and then Giacometti's figures appeared to me. I saw a clear relation between the two. I drew, several sheets with more or less precise experiments. After some time, I thought, that's it, that my etching would be born, that I had the right, the opportunity to leave behind paper for copper, but something else came, more imperious every time.

[. . . .] So here I am very alone with my solitary figures.

For the moment, it could be called Movement. At first, it was, almost bizarrely, Hommage to Giacometti and to the Burnt Pines of Estérel! Do I stick with Movement or do I push toward Giacometti and the pines? Not, of course that it will be this title!!?

Maybe I will wait until your return to make an etching! Maybe I must stop and make a different etching in the first direction. I don't know, I don't know. The temptation!!

— Giselle Lestrange to Paul Celan, 9 September 1965

2

Description of a workshop I did for Bending Genres a few years ago… with more coming soon, but different!

3

Alberto Giacometti’s The Palace at 4 am (1932).

4

Giacometti’s studio in my head and drafts today— the spectral possibilities in the sky of it.

5

The table of contents for Michel Leiris’ Brisees — and the “stones for a possible Alberto Giacometti” on page 132.

6

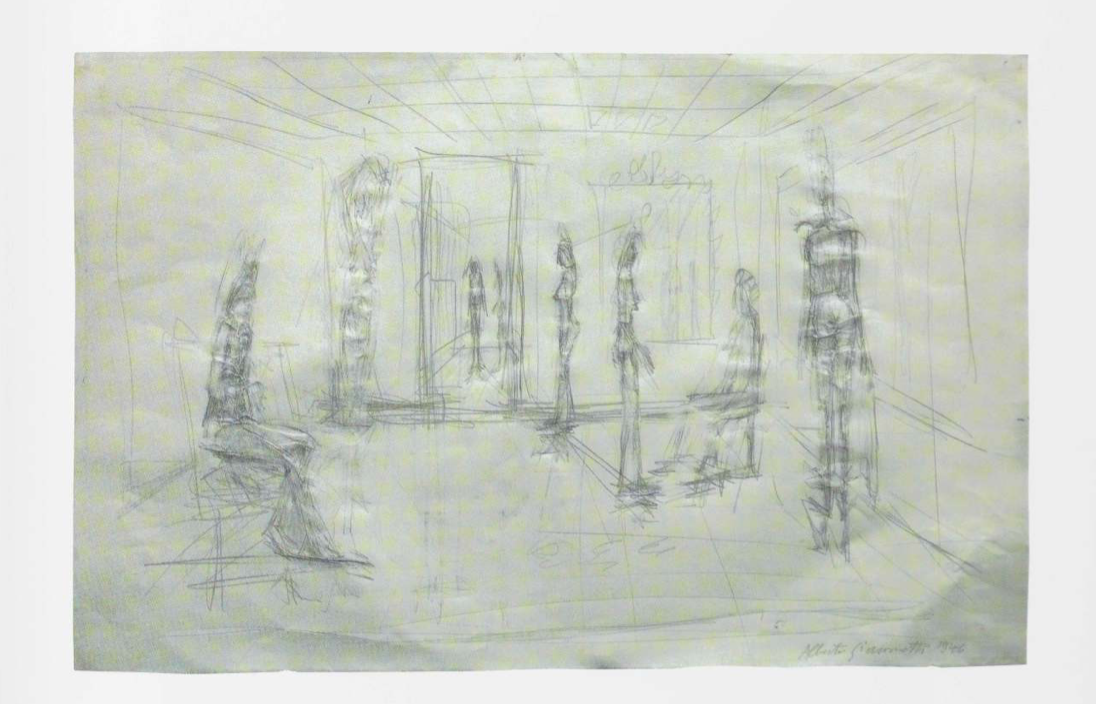

Alberto Giacometti’s Interior (1949).

7

At which point I admit to wandering back through Alberto Giacometti’s “The Dream” (as translated by Barbara Wright) while studying his interiors.

8

At which point I obsess over Giacometti’s efforts, as he keeps knocking his head against lines, and looking for ways to figurate the dream, moving between planes and geometries with his symbolic representations. With dreams, “the time factor” is the most troublesome aspect, precisely because dreams, by definition, are out-of-time, disloyal to temporality, the soft-drug of surrealisms. Boxes and squares may be where we start, as G did:

9

At which point I return to my notebooks on Saul Steinberg, and find the portrait I thought I remembered, which Steinberg captions as follows:

Giacometti’s face was rough creased by deep lines horizontal vertical and diagonal — The color was often unhealthy —

The hairdo was exploding steel wool. In repose he looked angry —

But when he liked something a smile of infinite kindness illuminated and transformed his face

(He had also an unexpected resemblance to Colette)

Saul Steinberg, Giacometti (1983)

10

Interiors move between spaces of apprehending and apprehension . . . places where we are seen, recognized, misunderstood, remembered, and perhaps even implicated in our own demise/s. In the Translator’s Note to Michel Leiris’ Frail Riffs: The Rules of the Game, Vol. 4, Richard Sieburth describes a portrait of the author at the point of being a “recovering corpse”:

Always entranced and terrified by the specter of his own demise— his autobiography should perhaps more properly be labeled an autothanatography– [Michel] Leiris became more and more intrigued by the possibility of his own posthumousness as he advanced in years. In Fibrils, the third (and he believed final) volume of The Rules of the Game, he recounts how at the age of fifty-six he had attempted suicide in the wake of an evening of heavy drinking occasioned by a messy extramarital affair that he could not bring himself to confess (as was his usual cathartic practice) to his wife, Zette. Caught in an impossible double bind of deception and need for punitive forgiveness, he swallowed five grams of phenobarbital in her presence (an act he assured her was mere "literature") and was transported to a local hospital, where he spent three days in a coma, undergoing an emergency tracheotomy just to keep him breathing. Upon his release, still barely able to speak, scarred at the neck (and hence symbolically decapitated), he was sketched by his friend Giacometti in his bed as a recovering corpse — a Lazarus (or perhaps, more accurately, a Scheherazade) rescued from the dead.

Nothing could be more Leiris-pilled than this portrait. Would that each of us could have a friend as reliable as Giacometti to memorialize us at our most unacceptable and unbelievable instances!

11

At which point I leave you with a few more interiors by Giacometti, across time. . . noting the beauty of Giacometti’s decision to populate sketches of his studio with the sculptures and plastics that are in the process of being created, unfinished and yet incredibly alive. Ode to the company of the creatures that have not finished with us yet.

Good, I will come to an end. One would perhaps have to advance on spindly legs, like these Giacometti men of whom you speak so well in your letter, but there again, don't you think, one ends up in the foundations.

— Paul Celan to Giselle Lestrange, 20 August, 1965

Postlude

Wherein I return to his studio just once more — for the last time — to retain an imprint of what his hand have done in the most secret and untouchable part of my mind. How the mind blazes in these studios, whether they belong to artists one has known personally or studied obsessively — friends, lovers, acquaintances, living, dead, “recovering corpses” . . . “I would come in a shirt of hair / I would come with a lamp in the night / And sit at the foot of your stair,” to quote Eliot.