The I that speaks puts forth — into the void that desire alone makes habitable — a world I no longer possess.

— Dan Beachy-Quick

You're like a messiah, kid

Little kingdoms in your chest

— Broken Social Scene, “Almost Crimes”

1

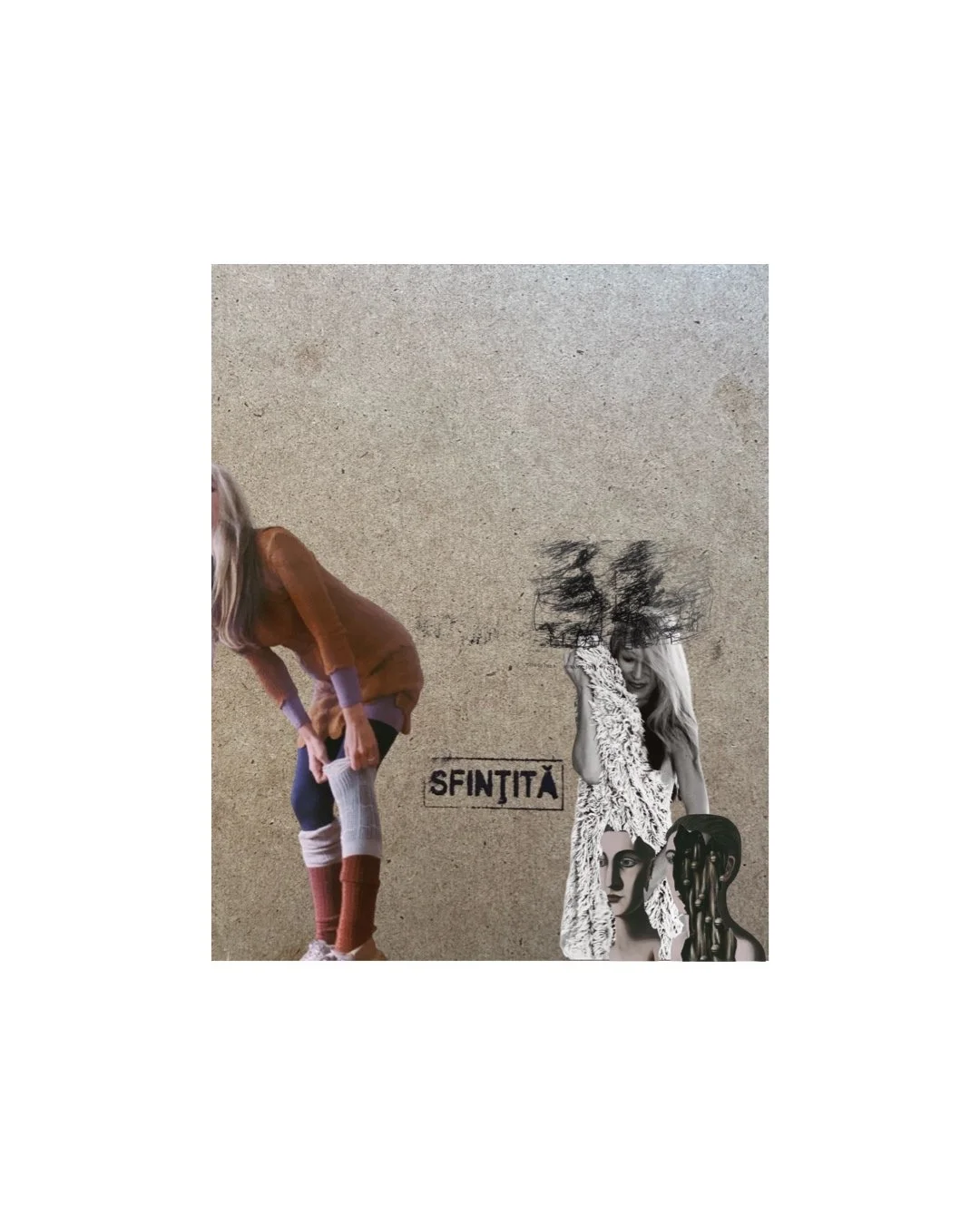

In Romanian, sfințită means “holy, blessed, consecrated, sanctified, hallowed, sacred.”

When my mother died, I brought her Eastern Orthodox icons into our home, where they sit in awkward dialogue with paintings, books, sketches, house plants, tennis rackets, and various items belonging to the teens. Some of the icons have a stamp on the back which marks them as “blessed” (sfințită), indicating that they have been officially “blessed” by monks or priests, according to the rules laid out by the relevant Orthodox institution.

I do not know what it means to be blessed—- or to be cursed. To be saved or to be damned. Poetry offers rooms that allow me to nibble on the proximity of these binaries, these couples defined by their complete opposition. Often I find my way into words by playing with images. Play, too, can be a form of profanation. Just as “Bless your heart” is a profanation of the good will inherent to blessing.

2

We are susceptible to the feeling of being trapped in time; we are vulnerable to the awareness of its limits. Time is both an idol and an idol-maker.

The sin of idolatry, in particular, has been levied against the icon. Idolatry begins where images – paintings, Marilyn Monroe posters, texts, constitutions, crowns, flags – are venerated in common, forming communities around a shared veneration. Appropriateness becomes the measure of good, and decorum creates a code of legible behaviors that are interpreted as respectful, where showing respect may also be a means of asserting social status. A man removes his hat before entering a church. But he doesn’t do this for god: he does this for the audience of others who might see him.

Rituals develop in order to define the appropriate relationships to the icon (i.e. how to fold the stars and bars correctly), but ritual cannot retain meaning if interpretation is relegated to an intermediary authority. One goes through the motions and mistakes the motions for life, for being, for breathing, moving, choosing, deciding. At this point, the icon loses its avenue to the ineffable, becoming, instead, a sort of painted opaqueness which occludes instead of revealing the inspiring experience they gave rise to its form.

Defacement or disfigurement places the icon in a state of desecration, or one in whose holiness has been removed.

3

Literature, like life, offers us ways of imagining freedom in relation to duration, where ‘taking up time’ becomes a measure of value. Resignation makes a subconscious pact with fatedness: “This is how things will be, for they can be no other way.” “This is the hand I’ve been dealt, and it was bound to happen to me.” “This is my curse.” “This is the curse of my blood-line.” “This is the fate of my people.” etc. etc. etc.

“The fated man looks for the choice that is choosing him,” wrote Dan Beachy-Quick. The heart of the heroic quest, its epic form, involves being defined by what one has chosen to do. To some degree, writing, or the decision to write, to pursue a life in writing, borrows from this convention. Just as the reader recollects the ocean breeze and the tartness of tangerines when reading Proust, the writer recalls the places, faces, voices, and images that animated her interior landscape when writing the book. The experience of reading makes those worlds available to us again.

4

Rigidity is the root of any religious fundamentalism. And literary criticism, like art, continues to wage the same battle between sincerity (often coded as realism or representationalism or authenticity) and fakeness (often coded as decadence or queerness or disorder). The real, to many of us, is that which has meaning, a position that often commits us, inadvertently, to a facile materialism. The house is real. The car is real. The published book is real. The private or intimate is thus less real or less true, in our calculus.

I realize this sounds conclusive, even though conclusiveness is anathema to me. My mind returns to the icon, the stamp that designates the “blessed”, and the belief structures that underpin ideals of blessedness (as well as ‘greatness’, in the sidereal). Arguing over the meaning of what exists in an image also has this relation to the literalism of the icon. While iconoclasm can be liberating, it may come to resemble reformation or revolutions that try to recapture and restore the idea behind the corrupted form. In other words, there can be a new reach for purity inside that desecration. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Iconoclasm isn’t fated to lionize a new purity.

5

I haven’t laughed often in the past week, but I did laugh this morning when reviewing my notes and remembering that Italian Futurists vowed to “kill the moonlight” in order to rid art of maudlin sentimentality.

6

When a text is consecrated, whether religious or secular, there are very strong limits put on its interpretation. The US Constitution, the Bible, the Koran – these are authoritative documents for certain communities, but circumstances change and a literal interpretation of a text considered authoritative becomes incompatible with peoples' lived reality.

Oddly, an authority that is literal is one that cannot last.

To last is to withstand the test of time.

To invoke a test of time is to resort to the authority of metrics and measurements.

7

Part of the iconography of romantic love pulls from the quiver of martyrdom, in that queer space where the arrows of Cupid morph into arrows of the Roman soldiers aiming at St. Sebastian. I’m thinking of T. S. Eliot’s early poem, “The Death of St. Narcissus,” which closes by blurring these arrows at the site of a sacred dance:

First he was sure that he had been a tree,

Twisting its branches among each other

And tangling its roots among each other.

Then he knew that he had been a fish

With slippery white belly held tight in his own fingers,

Writhing in his own clutch, his ancient beauty

Caught fast in the pink tips of his new beauty.

Then he had been a young girl

Caught in the woods by a drunken old man

Knowing at the end the taste of his own whiteness,

The horror of his own smoothness,

And he felt drunken and old.

So he became a dancer to God,

Because his flesh was in love with the burning arrows

He danced on the hot sand

Until the arrows came.

As he embraced them his white skin surrendered itself to the

redness of blood, and satisfied him.

Now he is green, dry and stained

With the shadow in his mouth.

Eliot didn’t want this poem published. He measured it against his later work and found that it didn’t deserve an eternity, which is another way of saying he feared it would not withstand the test of time.

There is no romance in utopia. There is no need for it. Nothing is lacking. An arrow in utopia can only be a relic of a time prior to the fulfilled time. Maybe this is another way of saying that perfection— the ideal of the absolutely good person— is incompatible with romance, since romance springs from a lack, and this lack has a relationship to desire. To want for nothing, to live in utopia, is to want for desire. To lack desire completely. Characters pass as if through a Proustian soirée, a tableau of sumptuous fabrics and palettes, an impression. But nothing coheres: nothing wants.

I am staring at the iconography of Saint Sebastian across the centuries, and thinking how the form has been shaped by what is excluded — whether it be the executioners, the body hair, etc etc. Any inventory selects what to leave out, if only the way light touches things differently. Any image inventories the objects that can be mentioned, or read.

This absence of how light moves— how light might have looked a moment later, or if standing five steps to the left of a window— remains an absence.

Telling a story about what happened in the past becomes a record of the past, limited.

The clock doesn't tell time because time is told by what is demanded of us – what we cannot forget, like feeding the goldfish.

Dan Beachy-Quick has said of the speaker, the poet, the writer: “The I that speaks puts forth — into the void that desire alone makes habitable — a world I no longer possess.” And yet— one can be possessed by the worlds one no longer possesses. Metaphysical language allows us to think through the affective mysteries and impossibilities of the human condition without focusing entirely on the “money”, so to speak. All the money in the world won’t satisfy our hungers for heavens or utopias. This is not to suggest in any way that socialism isn’t necessary and needed for humans to continue inhabiting this planet together. It is only to admit that socialism cannot ever fill the lacks and alienations that bring us to poetry or literature. Platonov’s Chevengur touches what theory cannot. As do the paintings of Sebastian. As does the music, whether Scriabin or punk or pop.

We've got love and hate it's the only way

I think it's almost crime

I think it's almost time

*

SAPPHO: I didn’t know it was like this. I thought everything ended with that final jump. I thought the longing and the restlessness and the tumult would all be done with. The sea swallows, the sea annuls, I thought.

— Cesar Pavese, Dialogues with Leuco