not touching you is a silence

in the discourse of touching you

but is a word

in the phrase of looking at you

- Ulalume González de León, “Syntax” (translated by Terry Ehret, John Johnson, & Nancy J. Morales)

Syntax—or the way the basic components of a sentence are arranged, connected according to phrases and clauses, and extended to other sentences—comes from the Greek syn (together) and tax (to arrange), meaning the orderly or systematic arrangements of parts or elements.

“Each is embedded in the syntax of the moment—” said Marvin Bell.

*

“The poem is itself essentially a body, comprised of various parts that work in various relation to one another–which could also be said, I know, of machines, but because poems are written by human beings, these relationships are unpredictable. A successful poem will never feel robotic or mechanized. It feels felt.”

- Carl Phillips, “Muscularity and Eros: On Syntax”

*

“The line is no arbitrary unit, no ruler, but a dynamic force that works in conjunction with other elements of the poem: the syntax of the sentences, the rhythm of stressed and unstressed syllables, and the resonance of similar sounds.”

- James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line

Longenbach’s three kinds of poetic lines include parsed lines, annotated lines, and end-stopped lines. O, kudos to Frontier Poetry for this resource!

*

“It is this question of grammatical phrasing and ending that orchestrates relationships between syntax and the poetic line.”

- Shira Weiss, “Syntax and the Poetic Line”

*

Lines can contain what is called a memory of meter rather than meter.

*

“Why not consider parallelism a type of prestidigitation, where subtle shifts in prosodic execution stack in such a way that we do not get the chance to see how quickly and sometimes violently the poem has changed? A word has been “put out of place,” a speaker who once held on to an orderly image of flying birds has become the very perch upon which the birds may sit. Meanwhile, the structure of the poem turns and entangles in its own (il)logic, and the likelihood of closure falls into deferment. But does not deferment of closure, of pleasure, carry the potential of intensifying pleasure once it finally arrives, a kind of driving one out of their mind?”

- Phillip B. Williams, “Wandering Through Wonder: Parallelism and Syntax in the Poetry of Carl Phillips”

More closely, Williams lists the following ways a poem can turn at the volta:

A reversal of what was just said comes into play.

A shift in mode: narrative to lyrical, lyrical to dramatic, dramatic to narrative, etc.

A shift in the spatiotemporal, meaning the when and where of the poem changes.

A shift in voice, meaning the actual embodiment of the speaker changes.

A shift in tone, often times signaled by a rhetorical shift. Meditative to enraged. Curious and deciphering into sure-hearted and self-engaged. Thinking about rhetoric, does the speaker move from listing to directive? Statement to question?

Each of these formal decisions—-each of these turns—-relies on choices about syntax. Each is an opportunity to make it “feel felt,” as Phillips has said.

*

“I mean, syntax is always about ascribing hierarchy, right? Syntax is a matter of who/what comes first, of what entity or force acts or is acted upon, and so on. When I play inside the constraints of this order, I’m playing so as to expose machinations that hum beneath familiar cadences, the under-rhythms and the ideas they carry. I want the arrangement to come under scrutiny. I love when syntaxes fold, repeat, contradict, and undo themselves to reveal their and our hypocrisies. I love the experience, while writing, of stumbling onto coded meanings in habitual language patterns and then defamiliarizing or destabilizing them. And I’m most interested in: What becomes possible after that?”

- Ari Banias in “The Politics of Syntax and Poetry Beyond the Border” by Claire Schwartz

*

“Syntax provides the opportunity for lines that are usually end-stopped, usually by means of a punctuation mark, and for lines that are enjambed because the sentence runs to the next line. Most free verse writers like to mix end-stopped and enjambed lines so as to create an individual sound, and to provide surprise and reward in the text. Syntax provides the opportunity for changes in pitch, pace, and tambour. Syntax and rhythm define a tone of voice far more than do vocabulary and lining. Line holds hands with syntax, and syntax holds hands with rhythm. The more kinds of sentences one can write, the more various can be one's poetry, whether metered or free. Syntax creates grammar and logic too, though in the end, music always wins.”

- Marvin Bell, after calling syntax “the secret to free verse” in a workshop

*

In an essay on Trevor Winkfield, John Ashbery described "sight-reading" a painting, or noticing how each element in the painting has "its precise pitch, its duration." One thinks of the hard, jewel-like poems that want to dissuade us from drawing closer. The quick clip of monosyllabic syntax and fricatives.

*

Language relates – and the words we use tell the reader what sort of relationship is brewing.

Haryette Mullen compared Stein’s syntax in Tender Buttons to “baby talk”, which she defines as "a magical marginal language used mainly by women and children.” For Mullen, the minor and the marginal are potential sites of freedom, and so she chooses the prose poem, which she also describes as a "minor genre," as the form to carry the words about gendered clothing in trimmings.

*

“Because many poets like a poem to look like a column, much free verse has the feel of accentual verse, in which one is counting the number of stresses in each line. These poems often are a conversational three-, four-, or five-beat line, with an occasional line a beat shorter or longer. Free verse at its most free verse-like is elastic: Some lines are noticeably shorter or longer than others, and each is embedded in the syntax of the moment. As a young poet, I sometimes follow the early example of William Carlos Williams and the later example of Robert Creeley, for example, enjambing short lines in jazzy syncopation. Thus, it seemed important to hesitate slightly at the end of each line.”

- Marvin Bell, again

*

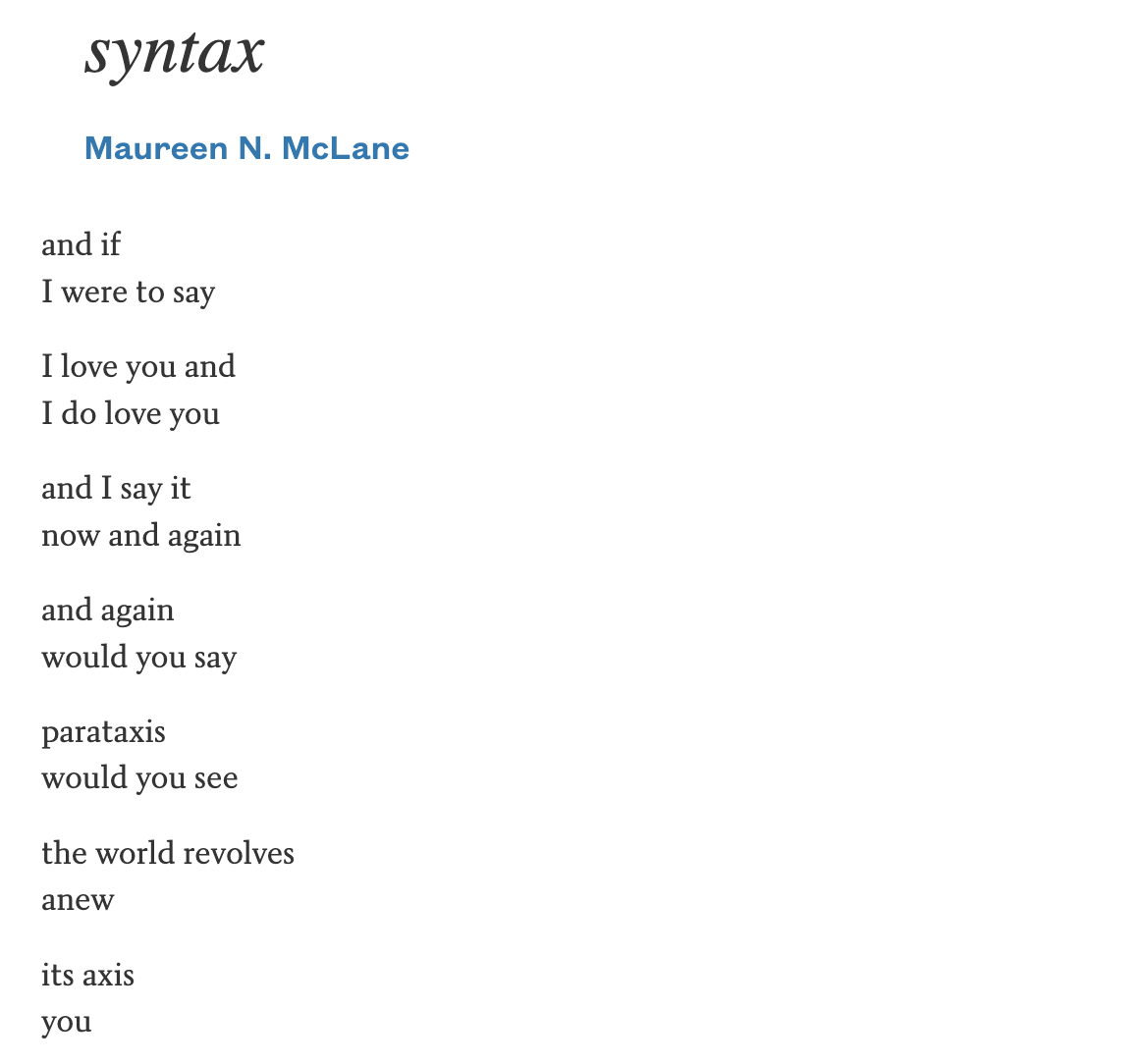

Metaphor positions us in a counterfactual relation to the world of ordinary speech and conversation. It puts us in what Anne Carson calls "an uncanny protasis of things invisible" which doesn't seek to argue with (or even refute) the known world so much as "to indicate its lacunae".

A counterfactual sentence can operate as a vanishing point for these two perspectives that lay in symmetry, or in protasis, in the conditional relationship. Syntax is how this vanishing is set up. Syntax determines its reach, texture, and duration.

*

"And we have to figure out what these coins mean, not

knowing the language."

- John Ashbery, "Flow Chart Part II"