I found a reference to Frank O’Hara’s “Ode to Necrophilia” in C. D. Wright’s essay “the new american ode.” Having never read this particular O’Hara ode, discovering an urge to do so, feeling needled by a vague curiosity, I searched for it—and settled for transcribing this visual screen-print created by by Michael Goldberg and Frank O’Hara in 1961.

Michael Goldberg & Frank O’Hara, "Ode to Necrophilia", screen-printed 1961. From the book Odes.

ODE ON NECROPHILIA

by Frank O’Hara

“Isn’t there any body you want back from

the grave? We were less generous in our

time.” Palinarus (not Cyril Connolly)

Well,

it is better

that

OMEON

S love them E

and we

so seldom look on love

that it seems heinous

This should be the end of the story, according to plot scheme mapped as 1) reader wants to eat a poem described a writer 2) reader finds poem 3) reader satisfies hunger with poem 4) reader makes notes on the feast itself. But the feast turned into a correspondence.

O’Hara’s ode fed me directly to Kati Horna’s gelatin silver print series, Oda a la Necrofilia (Ode to Necrophilia) from 1962. One year after O’Hara and Goldberg’s publication, Horna (who lived in Mexico City) created this photo-narrative of a woman grieving a death. Perhaps necrophilia was in the chemtrails of the early 1960’s.

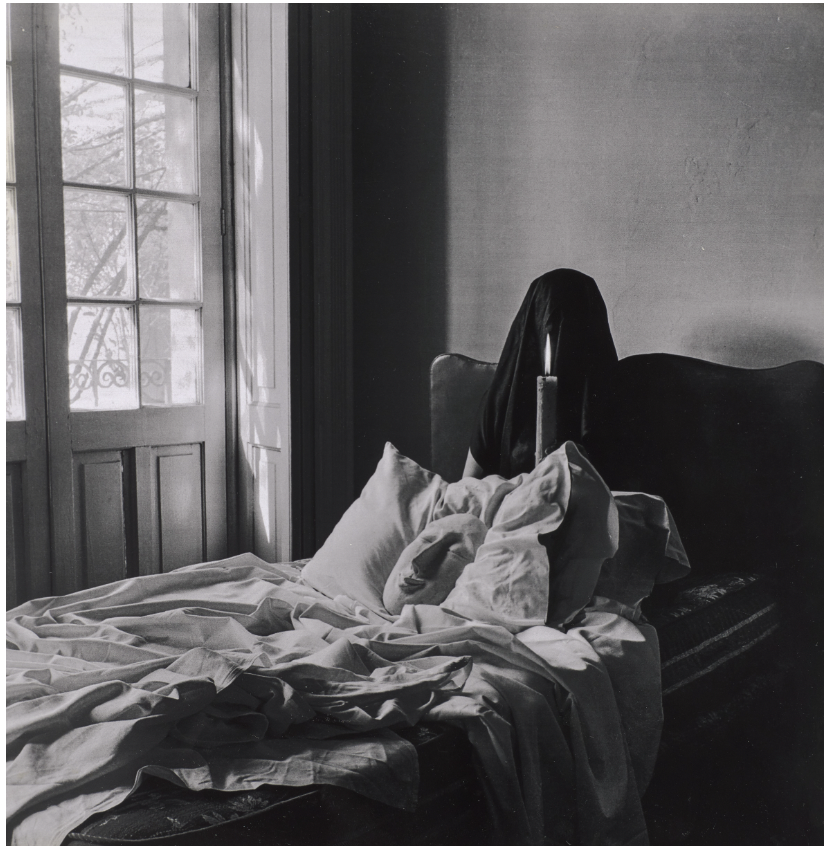

The Oda a la Necrofilia series was originally published in Salvador Elizondo’s avant-garde journal, S.nob, for which Horna coordinated the section on “Fetishes.” The only title I’ve found for the piece below is “Untitled.” It is incredible.

We know someone has died because the large plaster death mask lays on the pillow. At the head of the bed, hidden beneath the black fabric, a silhouette of a figure. The fabric is a mantilla, the traditional lace shawl worn by Spanish and Mexican women during mourning and on holy days.

Commemorative: the lit candle in the foreground. A half-open porch door with sunlight spilling onto the wall. The tension between the candle’s small flame and the bright light filling the room.

The figure beneath the mantilla is Horna’s friend and artistic collaborator, Leonora Carrington.

Leonora (Ode to Nechrophilia series), signed 'Kati Horna' (on the verso, gelatin silver print, sheet 8 1/8 x 7 1/2 in. (20.6 x 19.1 cm), executed in Mexico City, circa 1962.

Horna’s photo-narrative is silent, enigmatic, hued towards the erotic, and centered on Carrington’s interaction with various objects.

The shifting spatial relationship between the mourning body and the objects resembles a grieving process in which various defenses or forms or protective covering are shed. Once the mantilla is removed, the woman stands in her bra, smoking a cigarette, cradling the mask as if the absent could share the smoke with her.

The empty ankle-boots look so awkward poised ballerina-style near the bed. Are they hers or his?

Carrington watches herself smoke in the mirror to the left, and we see her reflection lit by the sunlight. The black umbrella is part of grief’s traditional costume in some villages, but I’m not sure if this is true in Mexico City, where Carrington posed for this photo series with Horna.

Clearly the black umbrella serves no useful function inside the room. If anything, it is—-like the cigarette and the cradling of the death mask—-a courting of bad luck. Opening an umbrella indoors is bad luck in most cultures. Is there a defiance in photo titled “Leonora”? Is there a risk?

There is—-I believe—a cigarette tucked behind Carrington’s ear.

The light moves to the white of the mask in her lap. The sheets are pulled back as if she is preparing to climb in bed with the mask.

The umbrella is open, hiding her face. A stroke of reflected light, like something shot from a mirror, on her left shoulder.

I don’t know the correct sequence of this series, so there is a sense in which I am inventing the story as I go, which means missing the story Horna intended.

Leonora (Ode to Nechrophilia series), signed 'Kati Horna' (on the verso, gelatin silver print, sheet 8 1/8 x 7 1/2 in. (20.6 x 19.1 cm), 1962. “Standing as fetish for the body of the deceased, a white mask carefully placed on top of a pillow becomes the recipient of the woman’s sorrow and desire.”

I don’t understand how Horna created this doubled-headboard effect. The shadow of the headboard interacts with the naked back and the absence of Carrington’s face in an extraordinary way— a melange of erotism and agony.

And the porcelain jug holding the candle: the subtle tension between this bedside, water-bearing vessel which is holding a lit object that lights the plaster face on the pillow. Grief is the story where form detaches from function.

The three images above are housed in L. A.’s Hammer Museum.

An inventory of moving objects in this series: the white mask, the candle, the pillow, the black mantilla, the unmade bed, the umbrella, the cigarette, the ankle-boots, the open book, the jug, the woman’s body in various states of undress.

A note on the artist: Kati Horna was born in Budapest, Hungary to an upper middle-class Jewish family. She learned her craft from the renowned photographer, József Pécsi.

In the late 1920’s and 1930’s, Horna moved across Europe from Berlin to Paris to Barcelona to Valencia taking photos for the illustrated press. Demand kept her moving through war zones in the interwar period, but it was Spain that affected Horna deeply, particularly after she got involved with the anarchist fringe in the Spanish civil war and began creating photos and montages for their propaganda materials. These anti-fascist agitprop materials combined satire with intense hope, two tones one can feel in Horna’s later work, where loss encounters itself as a continuous displacement, a reenactment among objects, a gestural dance with disillusionments.

In late 1939, as Nazism moved into the mainstream, Horna left the continent and settled down in Mexico City where other radicals and surrealists congregated. This is where she met Carrington, who had moved to Mexico knowing no one and speaking zero Spanish. Painter Remedios Varo had also come from Spain to Mexico, and Carrington and Horna may have rubbed elbows with other surrealist women, including Anna Seghers. (The international anthology, Surrealist Women, might have details, or else entirely disprove my wild speculations.)

Artist Pedro Friedeberg named Horna and Carrington as inspirations on his work and this should be the end of the end of the story about odes to necrophilia, if not for my failure to define the oded noun, itself.

Necrophila americana male (left) and female (right).

*

Necrophilia—-not to be confused with Necrophila, a genus of beetles—also known as necrophilism, necrolagnia, necrocoitus, necrochlesis, and thanatophilia, is sexual attraction or act involving corpses. It is classified as a paraphilia by the World Health Organization (WHO) in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic manual, as well as by the American Psychiatric Association in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

Adjacently, as reportedly inspired by O’Hara’s poem, in a stack of necrophilia and Twilight-hustling Goodreads posts—

It should also be noted that Marjorie Perloff, author of Frank O'Hara: Poet Among Painters, explained how Goldberg and O’Hara got involved:

O'Hara turned to art because the literary scene was so dead at the time. He disliked Robert Lowell, who was the prominent poet then but had no interest in the art of his day—especially not Jackson Pollock. Nor did [Lowell’s] contemporaries. O'Hara opened that up. When I wrote my book in 1976, saying that he was a notable poet of the period, people said it was ridiculous. Now there is enormous interest. The variety, good humor and charm in his work are tremendous.

Necrophila americana is a sonnet series waiting to be written by a suburban beetle in the auspices of a romance with a reading list.